History

The Soviets and the JFK Conspiracy Theorists

We can learn far more from the files still under wraps in Russia and Belarus.

Editor’s Note: This article was adapted from Fred Litwin’s new book, I Was a Teenage JFK Conspiracy Freak. For further information, please visit www.conspiracyfreak.com.

It’s an open question whether the Russians successfully tilted the 2016 American election to Donald Trump. We know they did their best, but we’ll probably never know if their attempts really shifted the vote. What is certain is that Russian attempts to influence American politics and public opinion are not new. Back in the 1960s and the 1970s, the Soviets tried to convince people that the CIA was behind the JFK assassination. 45 years later, we are still learning about the full extent of these efforts. In the following extract from my new book, I look at just three of these Soviet disinformation campaigns. They have had a demonstrable effect on the thinking and arguments of conspiracy theorists, and these, in turn, have gradually seeped into the wider popular culture and helped shape public misperceptions about the assassination.

The Mark Lane Connection

Some of the evidence of Soviet interference comes from the April 2018 release of JFK assassination documents, one of which related to the American conspiracy theorist Mark Lane. Lane was an attorney and civil rights activist, and one of the earliest critics of the official Warren Report into the assassination. In 1966, he published the first of a series of books on the assassination entitled Rush to Judgment, which would go on to become a bestseller. A CIA document discovered in the FBI’s file on Lane disclosed that, according to information obtained from an unnamed foreign government, the KGB had funnelled $1,500 through a “trusted contact” to Lane for his “work on a book” and $500 for a trip to Europe. The document says that “LANE was not told who was financing his work, but he might have been able to guess” and adds that, in 1964, Lane “wanted to visit Moscow and acquaint the authorities there with the revealing materials he had regarding the KENNEDY murder.”

But the Soviets did “not wish to enter into difficulties with the US” and so the trip was postponed. From then on, “trusted contacts among Soviet journalists met with Lane,” and he maintained regular contact with Genrikh Borovik, a Soviet writer, film-maker, and suspected KGB agent. In 1969, Lane again expressed interest in travelling to the Soviet Union to screen his 1967 documentary (also entitled Rush to Judgment), but “he was delicately told that the time was not right for such a trip, since the American government might begin a slander campaign against him in connection with his involvement in the anti-war movement.” Furthermore, “American communists who were in Moscow in 1971 expressed the opinion that, although LANE was engaged in activity that was advantageous to the Communists, he was doing this not without profit to himself, and sought to achieve personal popularity and become a national figure.” The CIA memo also claims that “other investigators and Kennedy assassination buffs were supplied by the KGB not only with money but also with circumstantial evidence that made the affair appear to be a well-concealed political conspiracy.”

The Clay Shaw Connection

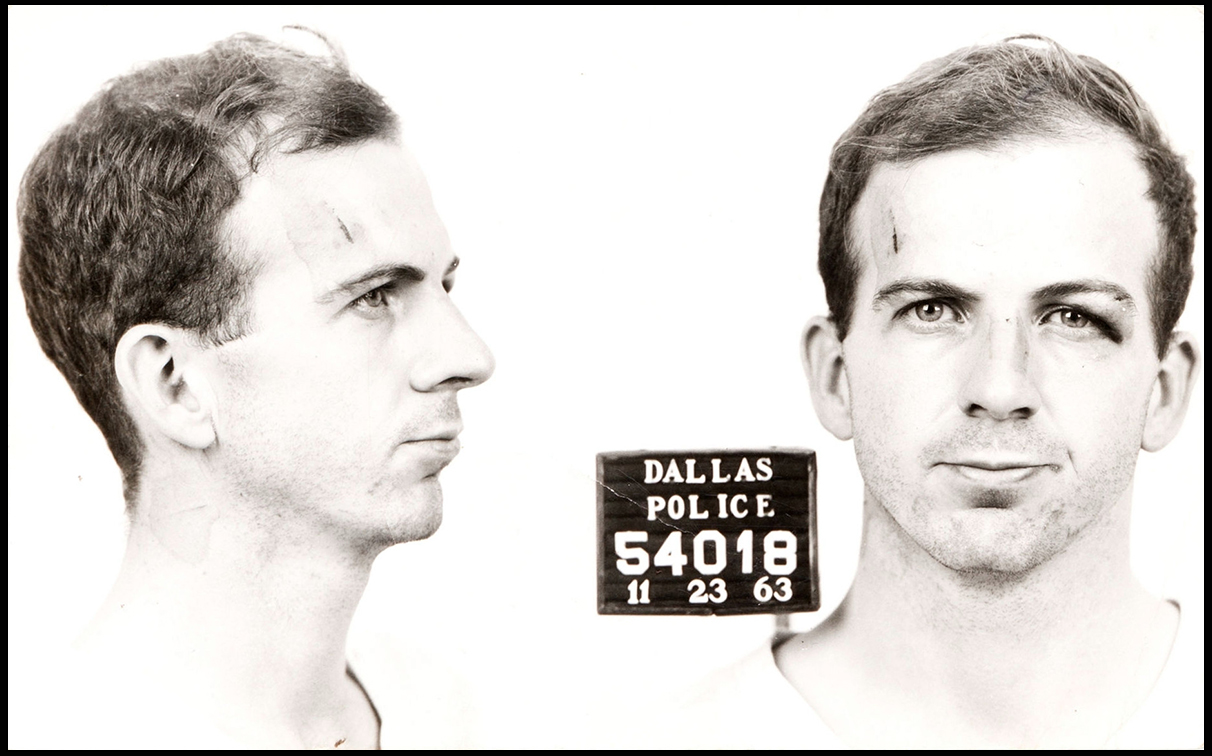

On March 1, 1967, gay businessman Clay Shaw was arrested by New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison and charged with conspiring with Lee Harvey Oswald to kill President John Kennedy. This startling development and Garrison’s lengthy investigation, both dramatised in Oliver Stone’s epic 1991 blockbuster JFK, led to further instances of Soviet disinformation.

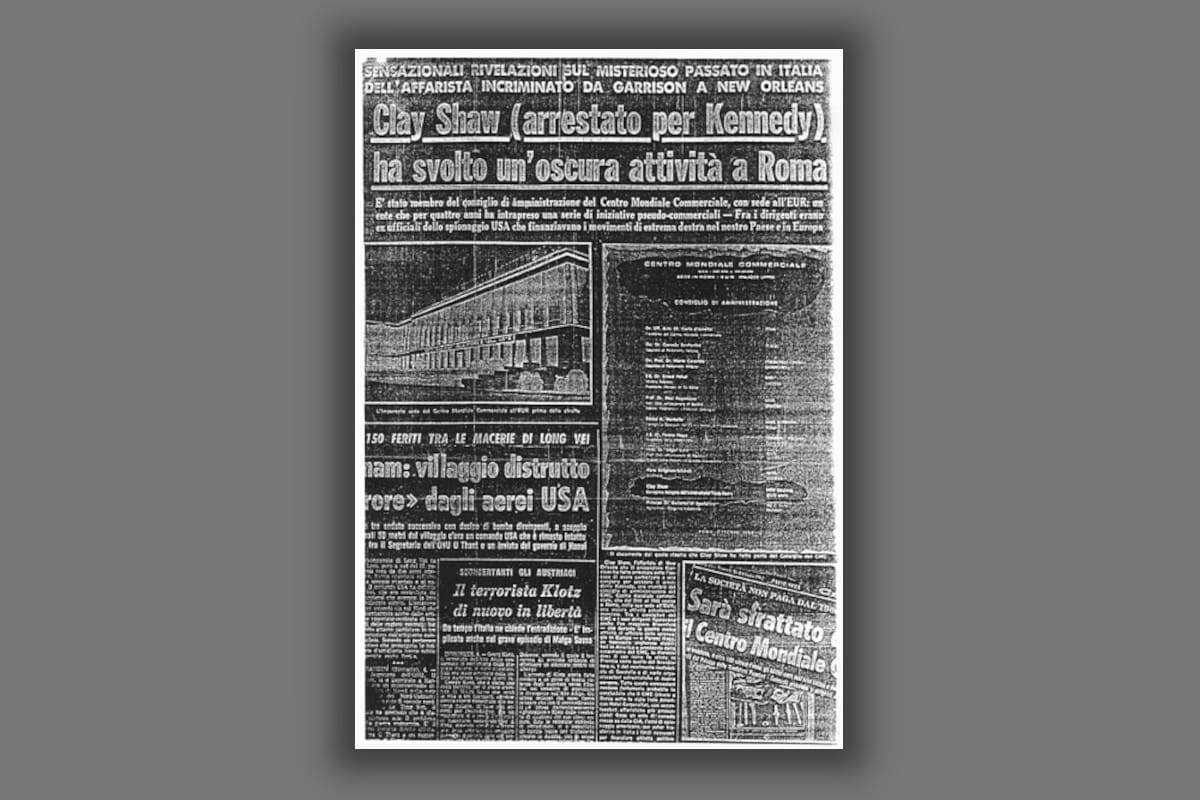

Shaw’s arrest reverberated around the globe. In Rome, a small Communist Party-owned newspaper, Paese Sera, ran a story on March 4 claiming that Clay Shaw was involved in unsavoury activities while serving on the Board of the Centro Mondiale Commerciale (CMC). Paese Sera alleged that the CMC was a “creature of the CIA…set up as a cover for the transfer to Italy of CIA-FBI funds for illegal political-espionage activities.” Shaw was indeed on the Board of the CMC from 1958-1962, but there was nothing sinister about the organization. Its purpose was simply to take advantage of the new European Common Market and to make Rome an important trading hub.

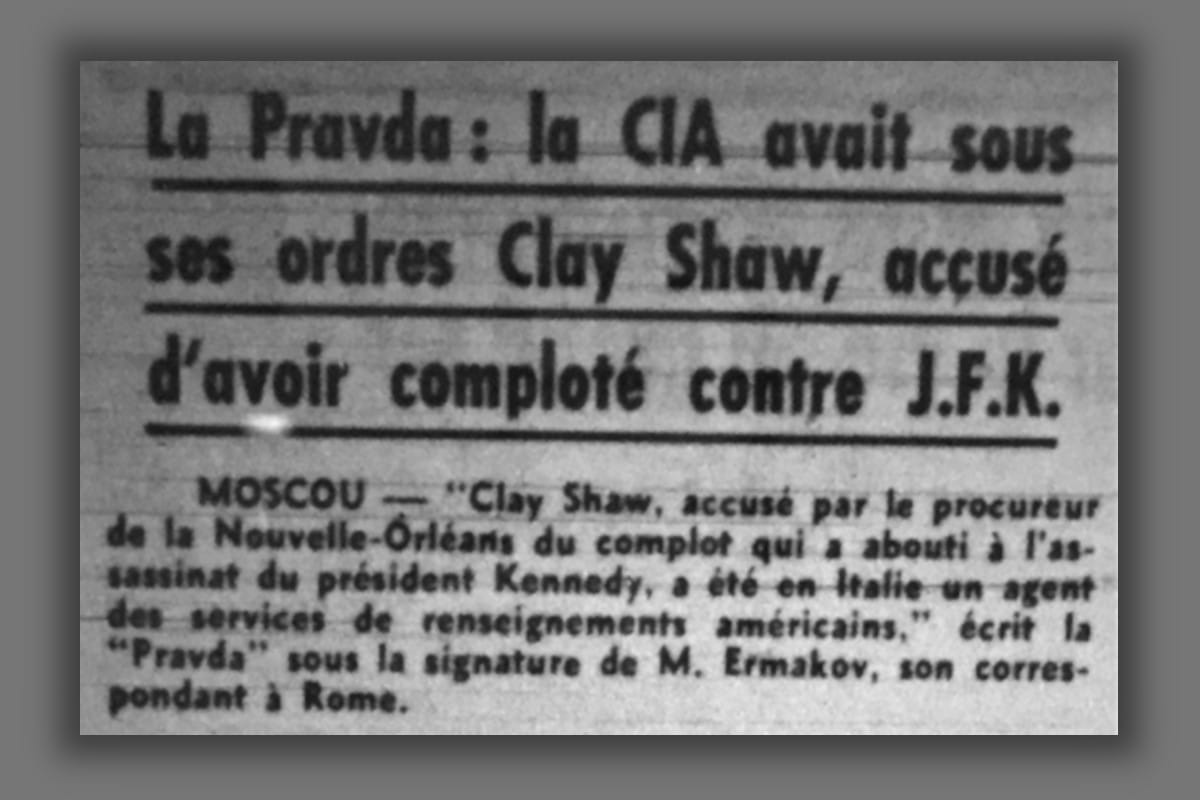

Nevertheless, the Paese Sera story was reprinted in Pravda (the official newspaper of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union), L’Unita (the newspaper of the Italian Communist Party), L’Humanité (the newspaper of the French Communist Party), and, finally, in Le Devoir in Canada. Le Devoirran the article in the March 8, 1967, edition, followed by a longer article on March 16, under the byline of their New York correspondent Louis Wiznitzer. He listed the items confiscated from Shaw’s apartment and described him as a “Marquis de Sade.” He also alluded gratuitously to Shaw’s homosexuality, writing, “Finally, another detail that doesn’t lack for a certain spiciness: in his youth Clay Shaw published a story from which John Ford took his film, Men without Women.”

Clark Blaise’s article, “Neo-Fascism and the Kennedy Assassination” in the Sept-Oct, 1967, issue of Canadian Dimension, a left-wing socialist publication, referenced the articles in Le Devoir and noted that they have a “breezy disregard for documentation.” Blaise “expected to see the story spelled out that afternoon in the Montreal Star, or at least to see a solid article or two appear in the liberal journals. Nothing more ever appeared.” He was also disappointed that the New York Times never mentioned any of the details about the activities of the CMC and felt “it was useless” to write to CBC and NBC. Ramparts (a leading left-wing magazine in the 1960s), on the other hand, followed its radical comrades by running an essay entitled “The Garrison Commission” in its January, 1968, issue which referenced Paese Sera and Le Devoir as its sources on Clay Shaw and the CMC.

A persuasive body evidence now shows that Soviet intelligence would routinely plant misinformation in outlets like these. Between 1956 and 1985, KGB archivist Vasili Mitrokhin secretly documented the activities of the Soviet Union around the globe. His notes would subsequently be collected and released as The Mitrokhin Archive, after he defected to the UK in 1992. In a book co-authored with MI5 historian Christopher Andrew, Mitrokhin claimed that, “In April 1961 the KGB succeeded in planting on the pro-Soviet Italian daily Paese Sera a story suggesting that the CIA was involved in the failed putsch mounted by four French generals to disrupt de Gaulle’s attempts to negotiate a peace with the FLN which would lead to Algerian independence.”

The American historian Max Holland has written a number of articles suggesting that the original Paese Sera story about Clay Shaw and the CMC was also planted by the KGB. Holland found a note in the Mitrokhin archive which stated that: “In 1967, Department A of the First Chief Directorate conducted a series of disinformation operations … One such emplacement in New York was through Paese Sera.” Sure enough, an article in the left-wing National Guardian, which had previously published and promoted Mark Lane’s conspiracy theories, discussed Shaw’s arrest on March 19 and uncritically reproduced the claims made in the Paese Sera report. This technique was corroborated by a senior KGB officer, Sergey Kondrashev, who told Tennent Bagley, Deputy Chief of the Soviet Bloc Division in CIA counterintelligence, that “the most obvious route toward the broad Western public was, of course, newspapers, and magazines—planting articles in cooperative papers.” Paese Sera in Italy was among the examples Kondrashev cited.

By mid-March, 1967, Jim Garrison had received copies of the Paese Sera article, quite possibly sent to him by Ralph Schoenman, who was Bertrand Russell’s personal secretary. We know this from the diary of Richard Billings, a senior editor at Life magazine, who was a confidante of Garrison’s. His entry for March 22 reads, “Story about Shaw and CIA appears in Humanite [sic], probably March 8 … [Garrison] has copy date-lined Rome, March 7th, from la press Italien [sic].” Jim Phelan wrote in the Saturday Evening Postthat, after the Paese Sera article, Garrison’s switchboard “blazed like a pinball machine gone mad.” He now had a direct link from Clay Shaw to the CIA.

In addition, the plethora of left-wing conspiracy enthusiasts who had flocked to New Orleans convinced Garrison to move away from his initial theory that the assassination had been motivated by homosexual thrill-seeking and to begin theorizing about an ever-widening plot. Over time, Garrison’s conspiracy would grow to include “Minutemen, CIA agents, oil millionaires, Dallas policemen, munitions exporters, ‘the Dallas Establishment,’ reactionaries, White Russians, and certain elements of the invisible Nazi substructure.” But at the heart of Garrison’s thinking was some sort of massive CIA-planned assassination plot, although even that was somewhat malleable.

Clay Shaw was eventually found not guilty and the Garrison prosecution was exposed as a massive fraud. That didn’t stop Oliver Stone from making Jim Garrison the hero of his film JFK and Clay Shaw the evil villain. Stone, of course, makes use of the Paese Sera story, and does so with a subtle sleight of hand, characteristic of his slippery handling of facts. The Paese Sera story was published three days after Shaw’s arrest; but in Stone’s film, Garrison confronts Shaw with its contents before the arrest, thereby implying that it was part of what justified his decision to charge him:

Jim Garrison: Mr. Shaw, this is an Italian newspaper article saying you were a board member of Centro Mondo Commerciale [sic] in Italy? That this company was a creature of the CIA for the transfer of funds in Italy for illegal political espionage activity. It says this company was expelled from Italy for those activities.

Clay Shaw: I’m well aware of that asinine article. I’m thinking very seriously of suing that rag of a newspaper.

The “Oswald Letter”

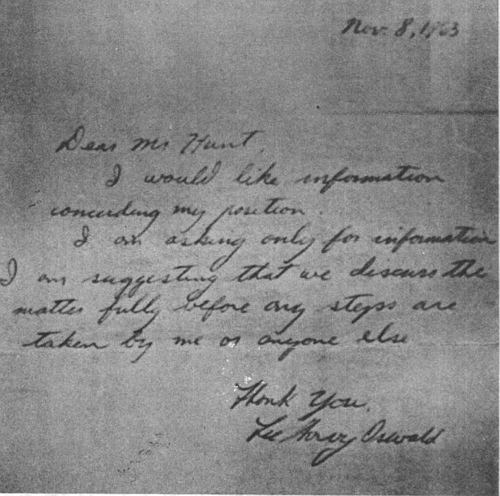

The recently declassified CIA documents mentioned above details another interesting KGB operation (also described in the Mitrokhin archive). In 1975, copies of a note that purported to be from Lee Harvey Oswald were sent from Mexico to three American conspiracy theorists. The letter, dated November 8, 1963, was addressed to a Mr. Hunt and said, “I would like information regarding my position” and “am suggesting that we discuss the matter fully before any steps are taken by me or anyone else.”

The note, however, was part of a Russian intelligence operation codenamed ‘Arlington.’ It was a Soviet forgery designed, the CIA document explains, to exploit “an assassination theory that was widespread in the US, according to which theory Howard HUNT, a former CIA employee, who was convicted in 1974 in connection with the Watergate affair, participated in 1963 in organizing a plot, the victim of which was President KENNEDY.” The KGB wrote the note using “individual phrases and expressions taken from letters written by Oswald during his stay in the USSR” on “a scrap of writing paper that OSWALD used in Texas.” Furthermore, “the note was on two occasions subjected to graphological and chronological examination ‘for authenticity’ by the Third Section of the KGB’s OUT (Operational-Technical Directorate).”

The note was then sent to assassination theorists Harold Weisberg, Penn Jones, and Howard Roffman. It was accompanied by another note saying that the document had been sent to FBI director Kelly and that he “has to date not done anything with this document.” The idea was to have the researchers ask the FBI to “produce the original note” and when Kelly denied he had received it, “this would encourage the investigator even more to obtain the desired document.” The operation was “carried out in such a way as to fuel [the flames of suspicion] with fresh news and to expose the participation of the American special services in the liquidation of KENNEDY.”

The problem for the KGB was that the conspiracy theorists tended to assume that the Oswald letter was intended for H.L. Hunt, the Texas oil billionaire, rather than for E. Howard Hunt, the former CIA operative. The first references to the document appeared in 1977, and the New York Times noted its possible authenticity.

Amusingly, the CIA document notes that “the FCD’s disinformation service believed that OSWALD’s connection with HUNT the millionaire, rather than with HUNT, the CIA officer, was purposely played up in the American press in order to divert public attention from OSWALD’s contacts with the special services.” The Oswald letter was later investigated by the House Select Committee on Assassinations which concluded that the letter was “much more precisely and much more carefully written” than other writings of Lee Harvey Oswald. They also professd themselves puzzled that Oswald’s middle name was misspelled—something he was not known to do—and were thus uncertain as to whether it was an authentic document. We now know that it was simply another operation designed to sow distrust and confusion.

Donald Trump’s decision to keep some of the JFK assassination documents secret caused huge consternation when it was announced in April of this year. But the explanation is straightforward enough—surviving informants must be protected and certain intelligence gathering operations need to remain confidential in the name of national security. In any case, the release of the outstanding documents has only been put back until 2021, and it is highly unlikely that we will learn much from them anyway.

We can learn far more from the files still under wraps in Russia and Belarus. Opening the Russian files could be useful in determining what else they did to influence American public opinion. As the declassified CIA document notes: “the KGB informed the Central Committee of the CPSU that it would take additional measures to promote theories regarding the participation of the American special services in a political conspiracy directed against President Kennedy.”

There aren’t many mysteries left in the JFK assassination. Lee Harvey Oswald killed JFK and he did so alone. There was no conspiracy, and any fair-minded person who looks at the evidence supporting the lone gunman theory will eventually arrive at the same conclusion the Warren Commission reached. But files still held in the archives in Russia and Belarus might yet tell us something about the efficacy of Soviet disinformation campaigns, and who else in the United States was either financed or duped by them, or both.