How New Orleans Became a Hive of JFK Conspiracism

Jim Garrison’s theory of the presidential assassination was based on false evidence and homophobic paranoia. Yet many still believe he was right.

The first outspoken proponent of a JFK conspiracy theory was Lee Oswald’s mother, Marguerite Oswald (1907–1981), who came to believe, even before John F. Kennedy was elected, that her youngest son was involved in a government plot. Mrs. Oswald became convinced as early as 1959, after learning of Lee’s defection to the USSR, that he was not the communist turncoat described in newspapers, but rather a US government agent who’d been sent to spy on the Russians. (At the time of the assassination, mother and son had hardly spoken since his return from Russia the previous year.)

After hearing Lee’s name in the news, Mrs. Oswald notified the local media of her availability, and took advantage of everything they offered in exchange for an exclusive story: car rides, hotel rooms, meals, money—anything that made her the center of attention. Nearly everyone who dealt with Marguerite Oswald before, during, and after that November weekend agreed that she was self-absorbed, jealous, demanding, vindictive, highly narcissistic, self-pitying, and generally out of touch with reality. She even told several people that weekend, and long afterwards, that Lee was the hero of this story, the one who tried to prevent Kennedy’s assassination; and that he should be buried alongside the president in Arlington National Cemetery.

Few took Mrs. Oswald seriously except for Mark Lane (1927–2016), a young attorney and civil liberties activist who came to be a well-known JFK conspiracist. On December 19th, 1963, a month after the assassination, Lane published a virulent critique of the Dallas police force in the National Guardian, a left-leaning publication, titled Oswald Innocent?—A Lawyer’s Brief: A Report to the Warren Commission. The piece highlighted apparent inconsistencies in the evidence against Lee Oswald—flagrant mistakes that, Lane claimed, would have served to exonerate him had he lived to face trial.

The article included a 15-point indictment of statements by Dallas District Attorney Henry Wade (who, truth be told, got as many facts wrong as he got right during an impromptu press conference on the evening of Lee Oswald’s death). For Lane, this was proof that the Dallas Police had charged the wrong man on the strength of falsified evidence and unreliable witnesses. Lane also argued that Oswald did not have a motive for shooting the president. “If Oswald were a leftist, pro-Soviet and pro-Cuban,” Lane wrote, “did he not know that during the last year, with the assistance of President Kennedy, a better relationship was in the process of developing between the U.S. and the Soviet Union?”

From that point on, Lane described himself as Oswald’s public defender, presenting the “facts” (as he saw them) in a way that proved his “client” had been set up. According to JFK assassination expert Vincent Bugliosi, Lane “elevated to an art form the technique of quoting part of a witness’s testimony to convey a meaning completely opposite to what the whole would convey”—a methodology that became characteristic of JFK conspiracy literature more generally.

Through early 1964, Lane and Marguerite Oswald crossed the United States and travelled to Europe, raising funds and presenting the legal defense they thought Lee should receive. Much of their case was based on a selective reading (and misreading) of witness statements and Dallas Police documents that had been leaked to Dallas Morning News reporter Hugh Aynesworth (which Lane had managed to “borrow,” and never gave back). Lane would also attempt, unsuccessfully, to attend Warren Commission proceedings as the (by then) late Lee Oswald’s legal counsel, and then as Marguerite Oswald’s attorney—which earned him an invitation to be deposed about his conspiracy claims. In presenting his case to the Commission, Lane claimed that Oswald was photographed outside the Texas School Book Depository during the assassination; that Kennedy was killed by a “grassy knoll shooter”; and that Oswald’s damning backyard photographs were fakes. The Commission’s lawyers were unimpressed, and dismissed Lane as a pesky opportunist and unscrupulous shyster.

Yet Lane went on to become one of the most enduring and influential JFK theorists. He would assist New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison in his 1967–69 inquest into Kennedy’s murder, and produce popular conspiracy works such as Rush to Judgment (1966). Lane also would go on to represent James Earl Ray, the convicted murderer of Martin Luther King, Jr., and the People’s Temple, a religious sect led by the evangelical-socialist mystic Jim Jones, who instigated a mass suicide in Guyana in 1978. In both of these latter cases, Lane used the same sort of “evidence” he’d used to defend Oswald.

Lane made many converts in the US and abroad, mostly on the political left. The most famous was the aging British philosopher Bertrand Russell, who, like Lane, published a widely cited brief against the Warren Report before the latter was even published. Other hard-line socialists who critiqued the freshly printed report included formerly blacklisted American journalist Thomas Buchanan (Who Killed Kennedy?), German antifascist Joachim Joesten (Oswald: Assassin or Fall Guy?), former Progressive Party investigator and poultry farmer Harold Weisberg (Whitewash: The Report on the Warren Report), French Figaro journalist Léo Sauvage (The Oswald Affair), and American philosopher Richard Popkin (The Second Oswald). In addition to echoing Lane’s claims, these works asserted that Oswald had been an informant for the FBI and CIA, that he was impersonated by an imposter for months (or even years), that Oswald shot Dallas Police Officer J. D. Tippit because Tippit was in on the plot, and that Kennedy’s murder was ordered and financed by Texas oilmen. While these authors never received attention comparable to Lane’s, their books fed the rising swell of criticism and moral outrage of a younger cohort of conspiracists.

In the spring of 1967, Jim Garrison (1921–1992), the charismatic and controversial District Attorney of New Orleans, opened an investigation into Kennedy’s murder. Conspiracists across the country rejoiced that a high-profile jurist with the power to arrest and convict the “real assassins” was as critical of the Warren Commission as they were. An imposing figure both in stature and personality, Garrison was described by those who knew him as smart and quick-witted, but also obsessive, self-righteous, narcissistic, unapologetic, and neurotic. He had an Ayn Rand-inspired contempt for big government, especially federal institutions such as the FBI, with whom he had been briefly employed but quit, disillusioned.

Prodded by his conspiracy-minded friend, US Senator Russell Long, Garrison became convinced that Kennedy’s real murderers were hiding in plain sight within his own jurisdiction, and that they’d cavorted with Oswald throughout the summer of 1963. JFK conspiracy buffs flocked to New Orleans to offer Garrison their assistance. Editors at Life, Ramparts, and Playboy applauded the news, and offered Garrison prominent coverage. Other media, however, remained skeptical, as were some members of his own staff. Over the next two years, Garrison’s probe would profoundly divide the conspiracist movement and ruin many reputations—including Garrison’s own.

Garrison’s investigation initially focused on David Ferrie (1918–1967), a local man who’d been questioned by the Warren Commission in 1964 and then dismissed as unimportant. Ferrie was an eccentric character afflicted by full-body baldness (alopecia universalis), which he covered up using a wig and false eyebrows, as well as a former high school teacher and novice Catholic priest who’d been defrocked for homosexuality. He then became an airline pilot and was fired again after being arrested for soliciting sex from a minor. He later morphed into a right-wing zealot, attempting (unsuccessfully) to join an anti-Castro militia. Ferrie finally settled on earning his keep as a pilot-for-hire and part-time private investigator. Based on details from Ferrie’s personal history, and some crank calls made by one of Ferrie’s former colleagues, Garrison concluded that Ferrie and Oswald were connected.

By this time, Ferrie was working as an investigator for the legal defense team of New Orleans crime boss Carlos Marcello. Yet it was not Ferrie’s ties to the mafia that interested Garrison, but rather his homosexuality and anti-communist sympathies. Indeed, Garrison all but ignored organized crime in his investigation, despite the fact that it would have been the simplest (as well as, for Garrison, the riskiest) means of creating a conspiracist narrative in a place such as New Orleans.

Initially, Garrison came to believe that Kennedy died as a result of a “homosexual thrill-killing” masterminded by Ferrie. Garrison’s evidence was thin, but as several Garrison biographers note, he was not the type to let a lack of evidence get in the way of a conviction. He soon connected Lee Harvey Oswald to a scruffy man who frequented Ferrie’s apartment during the summer of 1963, a man known by several of Ferrie’s acquaintances as “Leon” (later identified as former pilot James Ronald Lewallen). Garrison not only (falsely) identified Leon as Oswald, but also assumed that Oswald had been one of Ferrie’s lovers. Since Ferrie had gone ice skating in Houston with some gay friends on the weekend of the assassination, Garrison became convinced that the true purpose of this “vacation” had been for Ferrie to serve as a getaway pilot—even if Houston was not much closer to Dallas than New Orleans and all of Ferrie’s movements that weekend were accounted for.

Garrison soon added Ferrie’s former employer, the deceased private investigator and ex-FBI agent Guy Banister (1901–1964), to his list of suspects—on the basis of a fake address—544 Camp Street—that had been stamped on some of Oswald’s pro-Castro pamphlets. From there, Garrison’s list grew to include several Anti-Castro Cubans, the FBI, the Dallas Police, the CIA, President Lyndon B. Johnson, and Jack Ruby. (The Ruby connection was based on the idea that Ruby and Oswald were gay lovers, as claimed by Melba Christine Marcades, a heroin addict and prostitute who said she’d worked as a stripper at Ruby’s Dallas nightclub). As with Ferrie, Garrison ignored Ruby’s connections to organized crime, instead focusing on alleged political and sexual links.

Garrison’s investigation hit a snag when Ferrie suddenly died in his apartment on February 22nd, 1967. (The New Orleans coroner judged it a natural death, while Garrison told the media that it looked like a guilty man’s suicide.) So the prosecutors moved on to Dean Andrews (1922–1981), an obese, jive-talking (as the expression went at the time) ambulance-chasing attorney who wore sunglasses indoors and specialized in defending homosexuals and cross-dressers against public indecency charges. Andrews, the Warren Commission revealed, made phone calls to Dallas the weekend of the assassination claiming that he was Lee Oswald’s lawyer. But since Oswald made no mention of a New Orleans lawyer while in custody (or ever), Andrews’s attempt to contact him elicited inquiries from suspicious FBI, Secret Service, and Warren Commission investigators.

Andrews, it turned out, had been in the hospital at the time of his calls, heavily medicated and fighting pneumonia. He was unable to produce any proof of ever having been hired by Oswald. But instead of admitting he lied to the FBI (a federal crime), Andrews told the Secret Service that he had been hired to represent Oswald by a man named Clay Bertrand. When prodded for Bertrand’s details, Andrews gave contradictory descriptions that suggest he made up the whole story. Authorities closed the books on Andrews, concluding he’d wasted their time with a shameless attempt to ride the president’s murder to stardom. Garrison, however, concluded that Andrews knew more than he claimed, and that Oswald and “Bertrand” were connected.

A thorough investigation by Garrison’s staff found no trace of Bertrand in New Orleans. So the DA concluded that “Bertrand” was an alias used by an important member of the local homosexual underground. Garrison soon locked his sights on Clay Shaw (1913–1974), a wealthy New Orleans businessman with international connections, whose first name happened to be Clay and who also happened to be gay. On little more evidence than what I’ve written here, Garrison had Shaw arrested and then took nearly two years to build a case against him. A mild-mannered six-foot-four man with broad-shoulders and wavy hair, Shaw looked nothing like the young, ruddy-complexioned, five-foot-eight, 175-pound “rascal” described by Andrews. But none of that discouraged Garrison, who labelled Shaw a “Phi Beta Kappa sadist” and a criminal mastermind with ties to the CIA.

Garrison then rounded up several controversial witnesses to connect Shaw to Ferrie and Oswald. These included convicted felon and drug addict Vernon Bundy, who told a 1967 grand jury that he saw Shaw by the shore of Lake Pontchartrain during the summer of 1963, handing money to a young “beatnik” holding a stack of pro-Castro leaflets. Another was Perry Raymond Russo (1941–1995), a young bisexual Baton Rouge insurance salesman who’d befriended Ferrie in the autumn of 1963. Russo told the grand jury that he had attended an “assassination party” at Ferrie’s home—a gathering of homosexuals and Cuban exiles that included Shaw, Ferrie, and Oswald, whom he described as a dirty-bearded character named “Leon”—and that discussion at this party centered on murdering the president with triangulated gunfire. These testimonies convinced the grand jury that the DA had cause to prosecute Shaw. This was the “high-water mark of excitement and hope” for JFK conspiracists. Garrison’s witnesses, however, would prove his undoing.

A few days after these hearings, the Saturday Evening Post’s James Phelan published an exposé, based on admissions and documents that Garrison had shared with him. These revealed that Russo had been drugged, hypnotized, and taken to Shaw’s house and Ferrie’s former apartment to help him “remember” past events. In other words, Russo’s grand jury testimony—the principal basis on which Shaw had been indicted—was largely fabricated by Garrison. NBC’s Frank McGee launched his own investigation of Garrison’s inquest and discovered that Russo had failed a polygraph test, a fact the DA had concealed from the grand jury; and that other Garrison witnesses, including Bundy and Ferrie’s young lover Alvin Beauboeuf, had been bribed, intimidated, or threatened so as to induce them to produce corroborating statements.

The Phelan article and the NBC probe had a marked impact on the public’s perception of Garrison, especially outside New Orleans. Journalists now made it their mission to expose him as a fraud. And many of his own staff and volunteers quit or were fired after Garrison accused them of being FBI and CIA spies. Yet Garrison remained popular, as many believed he must have more proofs up his sleeve. And even amidst the bad press, he solicited airtime on TV talk shows, gave lengthy interviews, and made speeches on university campuses. He also convinced the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to force NBC to give him a half-hour of air time to respond to the network’s allegations, which he used to lambaste the Warren Report as a “fairy tale.” The narrative he now presented, including on the Tonight Show with Johnny Carson, focused less on Shaw, Ferrie, and Oswald as homosexual thrill-seekers, and more on an ambitious right-wing government plot in which the three men were minor operatives.

With this ambitious new story, Garrison could more easily dismiss his journalistic opponents as agents of disinformation. The CIA, he told Playboy, killed JFK because he tried to normalize US-Soviet relations by making peace with Castro. They did this, he said, using several assassins, none of whom were Oswald, but which included three anonymous tramps. Shaw now was Oswald’s CIA “babysitter” in New Orleans, while Oswald’s friend George de Mohrenschildt played a similar role in Dallas. Ruby graduated from gay hitman to “CIA bagman,” anti-Castro gun-runner, and “self-hating Jew” in the service of “master racists.” Garrison also blamed Texas oilmen such as H.L. Hunt and claimed (on no evidence) that the CIA had stolen files from his office and bugged his phones.

In response to Garrison’s media campaign, CBS newsmen Walter Cronkite and Dan Rather produced an ambitious four-part investigation of Kennedy’s death that vindicated the Warren Report. In 1968, Attorney General Ramsey Clark prodded the Justice Department to review the autopsy evidence, partly to respond to Garrison’s claims that it was manipulated. The Clark Panel echoed the conclusions of the Warren Report, of historian William Manchester’s exhaustive Death of a President (1967), and of the CBS News probe. The two narratives were completely irreconcilable.

The Shaw trial began in January 1969 as a media circus. Russo and Bundy offered upgraded versions of their grand jury testimonies, by now compromised by news that they’d been bribed, drugged, or hypnotized. Russo backtracked on several of his previous claims, admitting to twenty-six factual errors in his original interview conducted by Assistant DA Andrew Sciambra, and said that he’d never actually heard anyone agree to kill Kennedy.

Garrison brought in more controversial witnesses. These included a group of civilians from Clinton, Louisiana, who claimed they saw Oswald, Shaw, and Ferrie together in 1963 driving through their small rural town. (Some of these also erroneously reported seeing Oswald’s wife Marina Oswald holding a newborn baby, a claim that didn’t align with the timing of the alleged sighting). Their testimonies were inconsistent and vague under cross-examination. Indeed, the entire Clinton joyride seemed to have had no obvious purpose except to help Garrison connect his suspects. Even more controversial was witness Charles Spiesel, a New York accountant who frequently visited Louisiana and claimed he’d attended another assassination party with Oswald, Ferrie, and Shaw—but not Russo. Under cross-examination, Spiesel was exposed as a disturbed paranoid who thought he was the victim of a conspiracy carried out by his psychiatrist, the New York police, former clients (15 of whom had filed malpractice suits against him), and total strangers whom he believed had secretly hypnotized him dozens of times and disguised themselves as his relatives.

The rest of Garrison’s case against Shaw had little to do with the accused; it focused on trying to prove that Kennedy was killed by multiple shooters. The Zapruder film, subpoenaed from Life magazine, was played to the jury over a dozen times. Several Dealey Plaza witnesses were called in, only some of whom claimed they heard shots or saw smoke from the “grassy knoll.” Marina Oswald and her friend Ruth Paine, JFK autopsy pathologist Dr. Pierre Finck, Dallas Deputy Sheriff Roger Craig, and many others were called in to testify. None offered substantiated proofs that the Warren Commission was fraudulent. In the end, the Shaw trial offered the public four weeks of exceptional theater, but little else. The jury remained unimpressed with Garrison’s evidence and acquitted Shaw of all charges after deliberating less than an hour. It was a massive failure for Garrison and for the conspiracist movement.

It also financially ruined Clay Shaw, put an end to Dean Andrews’s legal career, made a laughingstock of the New Orleans District Attorney’s office and many of Garrison’s witnesses, and may have precipitated David Ferrie’s fatal stroke. Its impact on the historical evidence is also tragic, as it made it harder for future researchers to separate fact from fiction. The New Orleans portion of the conspiracy narrative injected hundreds of unproven speculations, red herrings, and lies into what was already a maze of distractions. If Mark Lane can be faulted for digging that first rabbit hole, Garrison takes credit for turning it into an underground city.

After this, Garrison abandoned his quest to prosecute Kennedy’s killers despite his bold promise to “nail every one of the assassins” even if it takes 30 years. He would instead write three books on the subject. The first, A Heritage of Stone (1970), describes a conspiracy orchestrated by the CIA and the “military industrial complex” to stop JFK from ending the Cold War. It says nothing about his fruitless campaign to connect Clay Shaw to JFK’s assassination, nor his earlier theory of a homosexual thrill-killing. The second, The Star-Spangled Contract (1976), is a fictional conspiracy novel containing all of the paranoid themes Garrison fans are now familiar with: secret CIA murders, White House intrigues, creeping fascism, pulpy sex scenes, and a self-righteous lone crusader fighting an evil bureaucracy. His third and final work, On the Trail of the Assassins (1988), is a self-congratulatory account of the Shaw trial retold in the style of a hard-boiled detective novel.

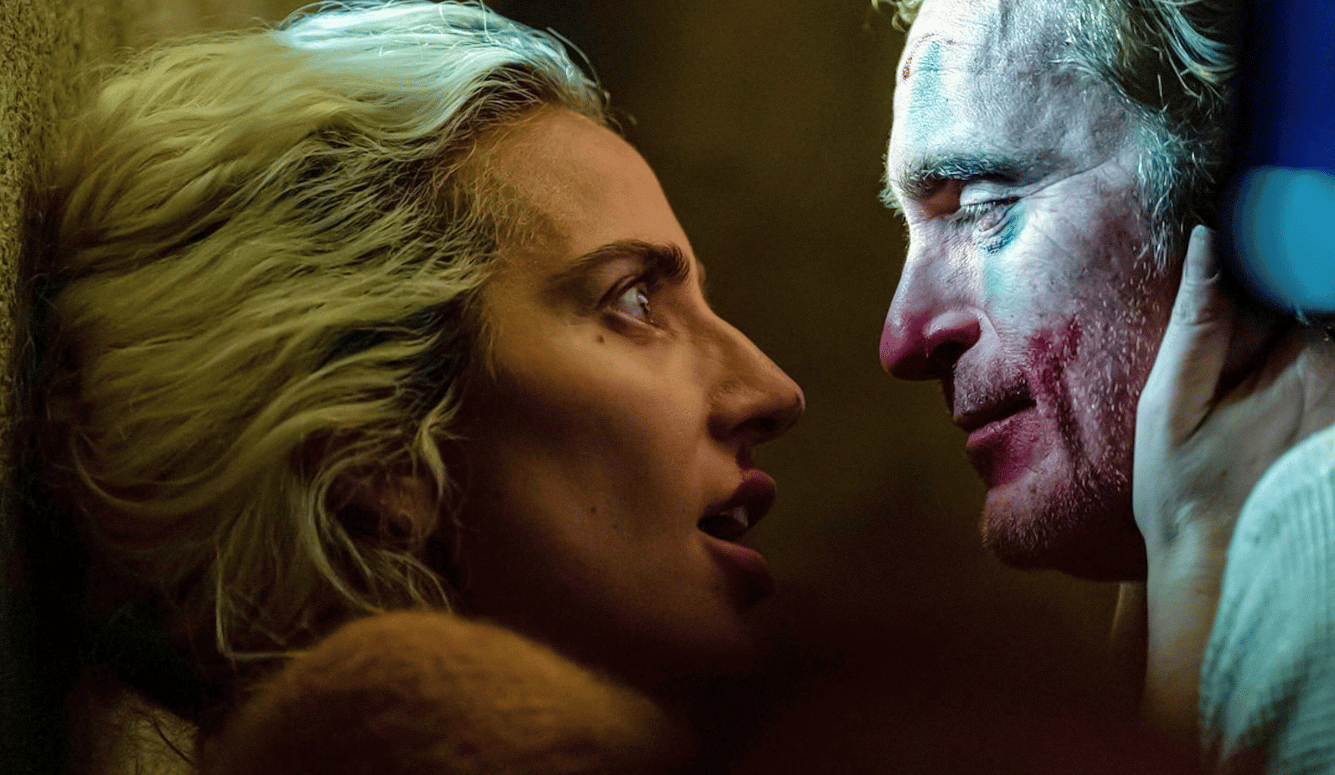

Conspiracists are divided over Garrison’s legacy. On one hand are those who accuse him of obscuring the “real” cover-up. Others, such as Jim Di Eugenio (Destiny Betrayed, 1992), Probe magazine publisher Lisa Pease, and Joan Mellen (A Farewell to Justice, 2005), have remained staunch defenders of Garrison’s claims that Shaw and Ferrie took part in the crime. Most famously, Oliver Stone based his 1991 film JFK in part on Garrison’s theories. Some defenders even managed to turn Garrison’s legal failure into a victory, a supposed proof not that his theories were false, but rather that the enemies were so powerful that they could scuttle the legal process he’s initiated.

Adapted, with permission, from Thinking Critically About the Kennedy Assassination: Debunking the Myths and Conspiracy Theories, by Michel Jacques Gagné, published by Routledge (2022).