Top Stories

Patriotic Reeducation

Chinese genocidal hatred against the Japanese simply cannot be dismissed as the bigotry of a nationalist fringe movement.

In 2017 in a rust-belt city in Northeast China I hopped in a taxi and began chatting with my driver who, when the conversation turned to politics, nonchalantly told me that he wished that the Chinese Government would kill every single Japanese person on the planet. I found this extreme to say the least, so I double-checked just in case my Chinese was failing me, “You mean kill every single Japanese man, woman, and child?”

“Yes, exactly,” he said.

Guessing by his apparent age I wrote my driver off as a fringe extremist whose possibly restricted worldview was likely shaped during the throes of the Cultural Revolution. I presumed that the vast majority of Chinese people today would decisively denounce this kind of violent sentiment of genocide. This presumption was wrong.

Chinese genocidal hatred against the Japanese simply cannot be dismissed as the bigotry of a nationalist fringe movement. Anti-Japanese sentiment is in fact so engrained in Chinese culture that it has become not only a political utility and form of patriotism but even a solid go-to branding opportunity.

The CEO of a major company in Hebei province sets his username on Weibo (China’s Twitter) to “killer of Japanese devils” and likewise a news anchor of a regional TV station sets his Weibo username to “destroy Japanese devils.” Weibo also has hundreds of users with the phrase “bomb Japan” in their username, and after a devastating 6.1 magnitude earthquake struck Osaka in June, the natural disaster began trending on Weibo with a large number of Chinese netizens lamenting that more Japanese people had not been killed. As one user put it, “The whole nation of Japan should perish as soon as possible. It’s an evil race that has infuriated god.”

Certainly not all Chinese hold such genocidal or hateful views. There is a sizeable minority that even frown upon these views and a growing number of more internationally-minded Chinese who have Japanese friends or study in Japan so are at the very least suspicious of this hate. Some Chinese even see this sentiment, in part, as a product of government propaganda and brainwashing. As the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) manages uncertainty over the future of its leadership, it exploits nationalism to boost its popularity and the painful memories of WWII anti-Japanese sentiment provides a relatively low-cost, high-yield opportunity for this purpose.

Chinese citizens who do openly support Japan in any way, shape, or form also risk being seen as traitors. Another user commenting on the Osaka tragedy remarked, “Any Chinese people in Osaka right now travelling or shopping? They should be buried together with the Japanese”.

In 2017, the China Badminton Super League told their own Lin Dan, the number one badminton champion in the world, that he would be forbidden from competing in the playoffs because he had a sponsorship contract with the Japanese sports brand Yonex. In 2012, the Chinese actress Li Bingbing refused to travel to Japan to promote her film, Resident Evil 5, saying that she “personally cannot handle it emotionally”.

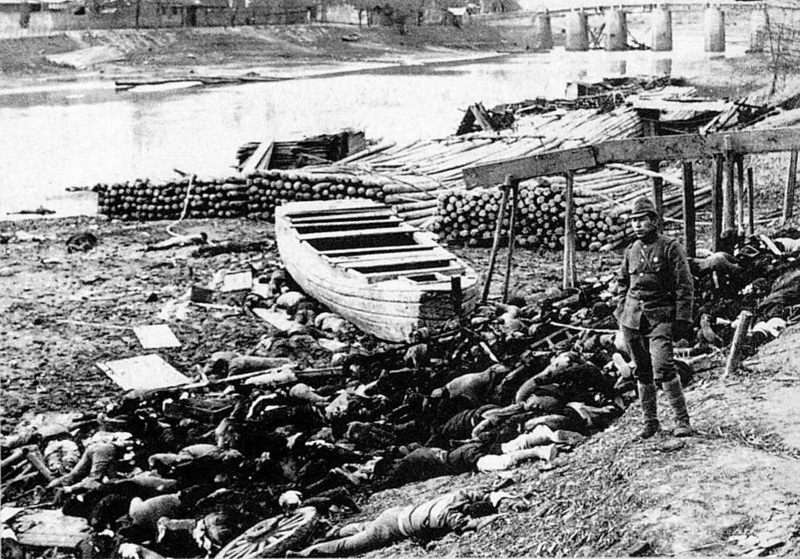

The origin of China’s anti-Japanese sentiment lies in the Chinese theater of World War II when the Imperial Japanese Army committed scores of harrowing war crimes on Chinese soil including the mass killing of civilians, sexual slavery, human experimentation, and cannibalism that resulted in the deaths of 10 to 20 million Chinese people.

While Chinese consumers punish those that associate themselves with Japan, they reward others that play to their anti-Japanese sentiments. The nation’s entertainment industry makes a lucrative business out of anti-Japanese war films and television series. As of 2013, more than 200 anti-Japanese war films were produced each year.

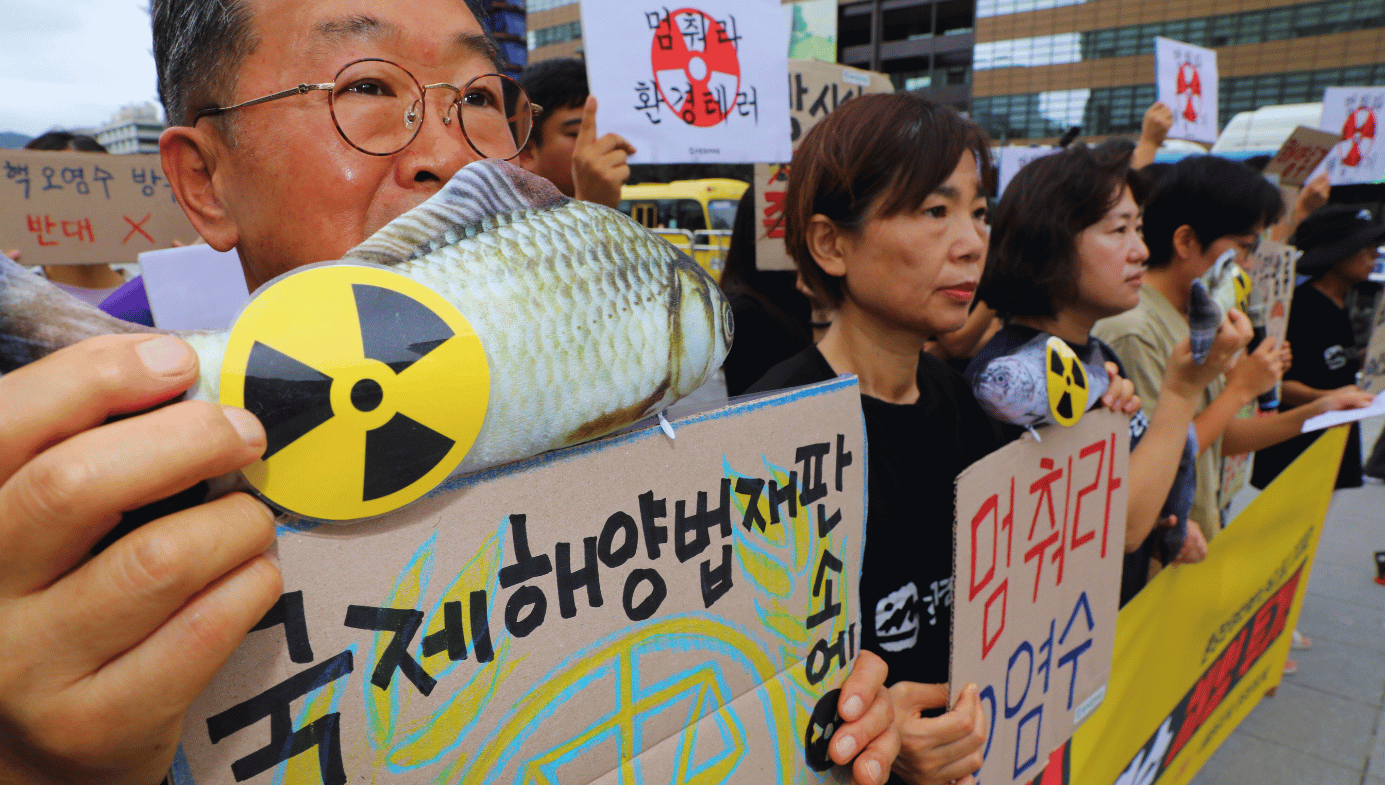

Most Chinese fervently believe that, unlike Germany, Japan has failed to adequately acknowledge and apologize for their WWII war crimes. As an example of a historical insult, a recently edited Japanese history textbookleaves out any mention of the many thousands of brutal killings and rapes of Chinese civilians during the Nanjing Massacre. Chinese people also harbor deep resentment over the Yasukuni Shrine, an elaborate Shinto shrine in Tokyo dedicated to Japan’s war dead, in which a number of Japanese war criminals are still venerated to this day. Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s visit to the shrine in 2013 sparked furor in China as well as in South Korea, a country that shares China’s anti-Japanese sentiment.[5]

While China’s anti-Japanese sentiment is clearly the inheritance of a profoundly hideous stretch of history, its current use of that history says a lot about China’s current political situation and how the CCP employs anti-Japanese sentiment as a political tool. For example, when the Japanese government purchased several of the disputed Senkaku Islands (claimed by China) from a private Japanese owner in 2012, Chinese nationalists were infuriated by the move and called for a boycott of all Japanese products. Demonstrators flaunted portraits of Mao Zedong and held signs reading, “kill all Japanese.”

These protesters may very well have been genuinely furious over the Senkaku dispute and about Japan’s WWII war crimes that resulted in the deaths of 10 to 20 million Chinese, but its hard to escape the fact that after the war the reign of Mao Zedong resulted in the deaths of another 45 to 80 million Chinese citizens. This of course raises the question: Is this genocidal hatred of the Japanese truly rooted in the historical atrocities committed against the Chinese people or is it simply a cynical form of nationalism built on a conveniently available outrage?

If this were really about brutal violence against the lives of innocent Chinese, the CCP would not only decisively denounce Mao Zedong, but it would direct more attention to his actions than to those of Japan. Instead, far from even denouncing Mao’s rule, the CCP, to this day, treats Mao Zedong as China’s savior and most revered leader. And while the Chinese accuse Japan of not owning its history, Chinese textbooks leave out any mention of the tens of millions of Chinese citizens that died during Mao’s rule.

Following the Senkaku protests The People’s Daily, a mouthpiece of the CCP, published an article on the incident stating, “the patriotic enthusiasm expressed by the people should be protected and taken extra care of.” The article responded directly to the protests with encouragement, saying, “We should understand, respect, and care for this sentiment, let the masses of people fully express their patriotic enthusiasm, and show the world our love for peace and our fight for justice against invasion.”

Fanning anti-Japanese sentiment serves a strategic advantage in the party’s promotion of nationalism, particularly when the CCP presents itself as a hero in defending the Chinese nation against Japan in bilateral disputes. Given the strength of lingering resentment, the government need only exert relatively limited effort for substantial patriotic fervor.

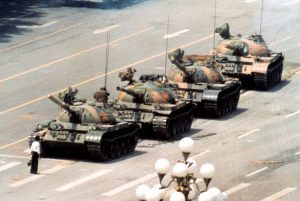

This use of nationalism as a tool for regime legitimation is linked with China’s recent political-economic transition (the one that ultimately launched the “Chinese economic miracle”). When the CCP reduced totalitarian control of Chinese society following the death of Mao Zedong, it had no plans for political liberalization. In fact, after observing the fate of other communist regimes, China’s reformist leader Deng Xiaoping and others felt that the best way for the CCP to attempt to retain authoritarian political control was to deliver prosperity through economic liberalization.

However, as the government loosened its grip on the economy and society, it became concerned that the people would soon call for political reform. These fears were forcefully confirmed when the Tiananmen Square protests erupted in 1989. The government surmised that its ability to deliver economic prosperity would be insufficient in ensuring the CCP’s political survival. It then began to focus on fostering nationalism in order to increase its popularity.

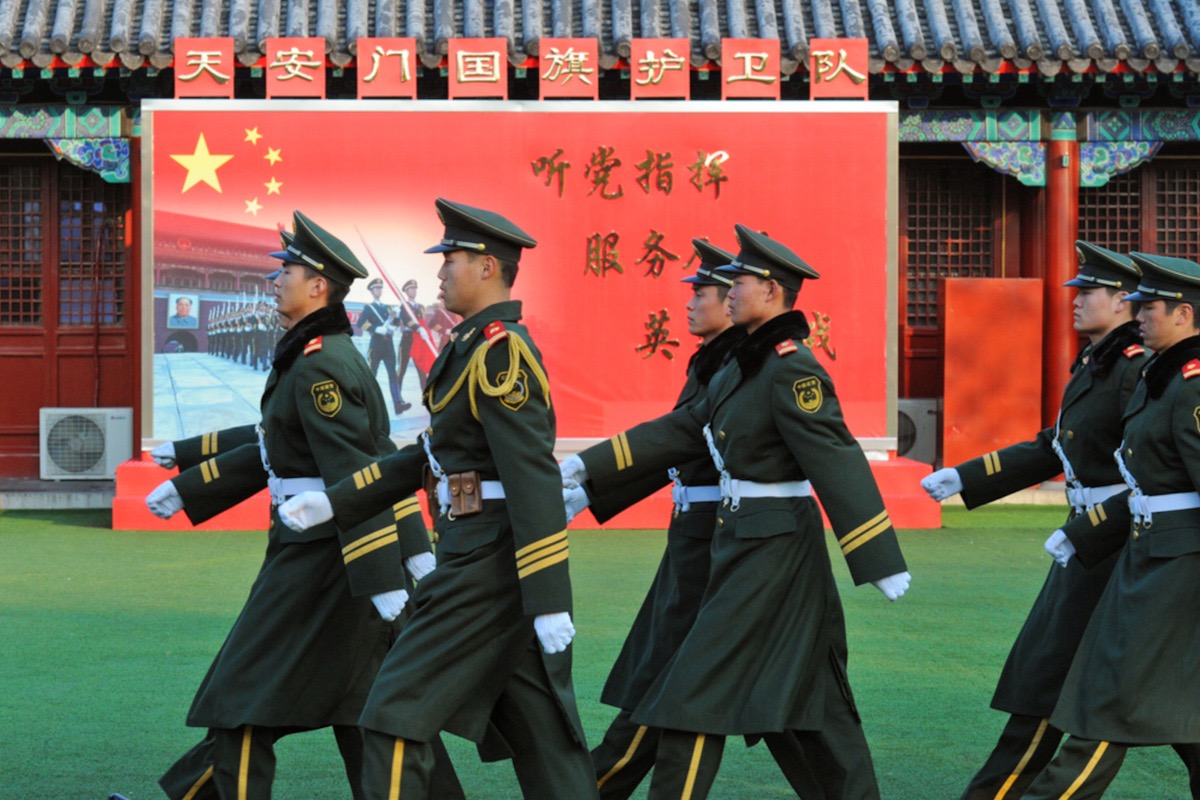

The CCP quickly launched a campaign of “patriotic education”, promoting a fiercely nationalistic ideology, in which the CCP is portrayed as integral to the conception of the Chinese nation. In this way, Chinese citizens are conditioned to believe that opposing or even questioning the CCP is almost synonymous with treason.

As official education incessantly emphasizes China’s history of victimization, it portrays the CCP as the primary defender of the Chinese nation against foreign antagonists. For example, last year, the CCP extended the official time frame of the war against Japan from 8 to 14 years to inflate the achievements of the CCP. The Chinese previously marked the beginning of the war with the 1937 Marco Polo Bridge Incident, when full-scale conflict began. Now, it is marked by the Japanese Invasion of Manchuria in 1931, at which time, the CCP engaged in small-scale fights with the Japanese army. According to the Chinese Ministry of Education, this change is specifically designed to promote patriotism.

This promotion of nationalism has unquestionably been effective in boosting support for the CCP but the country’s recent illiberal trajectory suggests that it hasn’t formed the pillar of legitimacy that it was hoping for. If the CCP were confident that the combination of nationalism and competent governance could secure its future, it is unlikely that it would govern with such repression. At the same time the CCP is well aware that, apart from a few petro-states, there is not a single case in history of an authoritarian country achieving high-income status (roughly double China’s per capita income today).

If enough people begin to grow tired of the manipulative nature of the official promotion of anti-Japanese nationalism, it may end up doing more harm than good for the CCP. But as things stand, while the CCP projects ever greater strength on the global stage and draws attention to its portfolio of lofty goals, it is rapidly reverting back to totalitarianism at home, the likes of which haven’t been seen since the era of Mao.