Art and Culture

The Problem with 'Facts Not Feelings'

The narrow emphasis on ‘facts not feelings’ reflects a widespread misunderstanding of the role evidence plays in the apprehension of truth.

In the midst of our turbulent political and cultural moment there endures an intellectual sub-culture that refuses to be dislodged by the relativism prevalent on the Left and the Right. In the crosshairs of postmodernist excess and ‘alternative facts,’ a number intellectuals and institutions are prioritizing moral and empirical truth over ideology. This is a space that includes organisations like the Heterodox Academy and the cluster of academics and public thinkers now known as the Intellectual Dark Web.

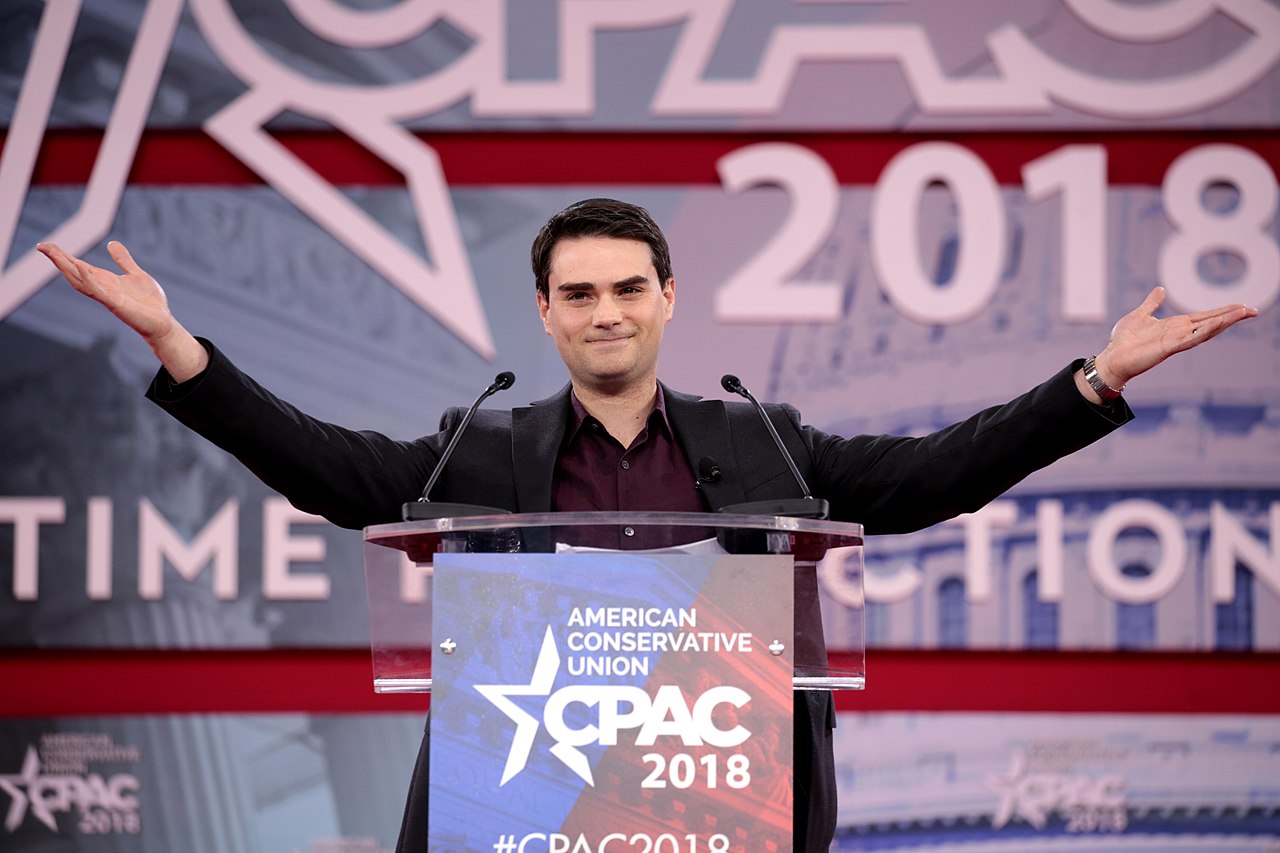

One of the brightest stars in this constellation is the conservative pundit Ben Shapiro—a gifted polemicist who has debated his way to prominence in American politics. With a podcast that reaches millions and a reputation for being as willing to criticize conservatives as he is to engage conventionally liberal thinkers in far-reaching conversations, Shapiro has given a face to popular conservatism that is strikingly more empirical and intellectually honest than that offered by the likes of Candace Owens, Steven Crowder, and Tomi Lahren. Nevertheless, one aspect of Shapiro’s message constitutes an over-correction that is itself in need of correction.

Shapiro is famous, in part, for touring college campuses and ‘destroying’ idealistic and emotional young progressives with the aphorism “Facts don’t care about your feelings.” However, there is an argument to be made on behalf of empathy in our discourse that is being heedlessly trampled by Shapiro’s defiant mode of aggressive argumentation. The narrow emphasis on ‘facts not feelings’ reflects a widespread misunderstanding of the role evidence plays in the apprehension of truth, which thwarts our ability to properly pursue empirical and ethical truth in the first place.

There is—or ought to be—obvious value in acknowledging the importance of facts when constructing and defending one’s worldview. The idea that undisciplined emotions distort the process of reason is an ancient one. When we look to the Left and see Ben Affleck leaping factual claims like hurdles in order to characterize Sam Harris’s views on Islam as racist, and then look to the Right and watch Kellyanne Conway describing provably false claims as ‘alternative facts,’ it reminds us that this bears repeating. Shapiro, therefore, has taken to intoning his admonition about facts and feelings repeatedly. During an appearance on the Rubin Report in January, Shapiro lamented the lurch away from evidence-based claims that American political dialogue has taken:

I’m not going to pretend that every opinion I have is a fact. But when there is a fact I try and distinguish it from my opinion. I’ll try to give you the fact and then say, “And now here’s my opinion on the fact.” Once we got away from the common basis of facts it’s very difficult to have a conversation at all.

Shapiro is, of course, right to say that our detachment from a common reliance upon facts makes conversation difficult. He goes on to mention that when he and his opponents can agree on the centrality of facts they are perfectly capable of having a cordial debate. This is all to Shapiro’s credit. Even so, his preoccupation with the decline of reasoned conversation in civil society also implies something else that is true—that the health of civic culture depends upon the restoration of functional dialogue. And this, like any complex and important issue, is more than just a question of facts per se. It raises the vexing question of how to communicate most productively with those who vehemently disagree. Is the proper strategy for accomplishing this to aggressively argue with people about what the facts are?

In 2014, at the age of 27, I ran against Maxine Waters as the Republican nominee for Congress in Los Angeles County. With little name recognition and no money, I was not taken seriously as a candidate by the institutional powers in my district. And yet, by the time the dust settled, I had managed to win 30 percent of the vote—a more respectable share than any of Congresswoman Waters’s previous opponents. As a black Republican, I am frequently asked how it felt to be called a ‘sellout’ and an ‘Uncle Tom’ over the course of the campaign. These are epithets that many on the Left sling at African-American conservatives such as Larry Elder, Clarence Thomas, Ben Carson, Hermain Cain, and black Republicans more generally. But, over the course of my entire campaign, I can hardly think of an occasion when those words were used to describe me.

Why does this matter? I can certainly remember occasions when people wanted to treat me poorly for being a Republican. I recall addressing a meet-and-greet at which a civil engineer responded enthusiastically to my every policy point until I casually mentioned I was a Republican. Thereafter, he challenged me at every turn. When I finished and passed around the signature form that would enable me to qualify for the ballot, he refused to sign, explaining “I just can’t help a Republican.” But everyone else signed, happily. On another occasion, I was invited to speak at a local church, only to sit through a 20 minute sermon from a guest preacher that could have been titled ‘Why Republicans are Pharisees.’ But when I was finally permitted to speak to the congregation for just two minutes, they responded with an ovation.

When I campaigned in South (erstwhile South-Central) Los Angeles, I never led with the fact that I was a Republican. I did not attack Maxine Waters, the Democratic Party, the federal government, or the progressive agenda. Nor did I disguise my views or my party affiliation. I led with statements of empathy for the struggles and aspirations of the community. I had differences of opinion with people whose votes I sought about whether or not the United States is an irredeemably racist country. But I didn’t declare this view to be wrong and list the data points (voting trends, increases in inter-racial marriage, the expansion of the black middle class, the popularity of African-American artists etc.) to debunk or ‘destroy’ their view.

Instead, I would speak to the feelings that had produced this view, acknowledging that the black experience in America has indeed been colored by a history of racism, and the myriad ways in which this history continues to have consequences for the present. I hoped to validate the understandable emotions that yield a perspective with which I differ. Having done so, I would tell the story of my father, a white man who had voted for Mitt Romney (and later for Trump), listened to talk radio, and yet was also a Jazz pianist who married a black woman, raised two black sons, and whose heroes in life were Willie Mays and Muhammad Ali. Only then did I proceed to list the statistical points that suggest that the United States, for all its inequality and faults, is not a racist country in anything like the way it once was. At which point people were willing to listen.

Differing opinions, even disagreements about facts, are not necessarily what leads to polarization. As Shapiro himself has noted, hostility is inflamed when our differences are perceived to be threatening to the validity of our identities and experiences. When disagreements are framed in a way that does not delegitimize the experiences of our opponents they cease to be emotionally threatening. And when disagreements cease to be emotionally threatening, it puts people at ease and affords them the space to consider new perspectives and ideas.

This observation echoes the main thesis of Jonathan Haidt’s The Righteous Mind, in which he argues that our faculty for reason labors to validate our intuitions (including our moral impulses), not vice versa. In Haidt’s analogy of the Rider and the Elephant (elaborated in the clip below), the Rider represents ‘strategic reasoning,’ whose direction is determined by the much larger and more powerful Elephant, which represents intuition and emotion. Haidt explains why so many debates fail to persuade, writing, “You can’t change people’s minds by utterly refuting their arguments…If you want to change people’s minds, you’ve got to talk to their elephants.”

Ben Shapiro’s tendency has not been to talk to elephants so much as make them stampede. Take, for instance, the now-infamous tweet he sent in September 2010 which read: “Israelis like to build. Arabs like to bomb crap and live in open sewage.” A fair-minded look at the tweets sent immediately after this one reveals that Shapiro’s assertion was made in reference to the Israeli and Arab political leaderships—not to these populations as a whole. Shapiro reiterated this explanation in a recent defense of the tweet at the Daily Wire, in which he describes the Left as “idiotic” for its collective failure to appreciate context.

But what Shapiro is really criticizing in his article is the willingness of people to be led by their elephants, even though this is inevitable and therefore entirely predictable. Regardless of any technical defense of the tweet disqualifying it as racist, if Shapiro’s objective as a good faith interlocutor is to invite people to consider new perspectives, then it is strategically unjustifiable. If, on the other hand, his intention is solely to enrage his opponents and electrify his supporters, then he is engaging in demagoguery and should not complain when people react exactly as intended.

If we are to talk to one another’s elephants in an effort to convince, we have to retain a capacity for empathy. If we discard empathy or treat it with boastful contempt, we sacrifice our ability to persuade, and reduce polemical prowess to an exercise in vanity. Eric Weinstein warned against this on Joe Rogan’s podcast saying (in reference to the Intellectual Dark Web) “I believe that fundamentally we are in danger of breaking empathy with people who do not express themselves in our idiom.” Indeed. The ‘facts don’t care about your feelings’ mantra is fair enough as a statement of the obvious. But as a moral statement, it is itself an expression of this very rupture of empathy.

Hyper-emphasis on the importance of facts strikes against our ability to properly understand those who disagree with us. It allows us to believe that their intuitions deserve our derision and condescension. The assumption that fidelity to fact is synonymous with Truth, in turn, leads to intellectual atrophy that frustrates both empathy and intellectual growth. As Eric Weinstein observed during his discussion with Rogan: “The claim that you fact-check has been synonymized with the claim that you are truthful, which is utter nonsense.”

Facts are unquestionably vital to the pursuit of understanding. But the possession of facts alone does not guarantee an accurate or optimal interpretation of those facts. How we feel about a set of facts has everything to do with how we interpret them. And how we interpret facts is, in part, a matter of values. Elsewhere in The Righteous Mind, Haidt theorizes that we rely for our intuitions upon moral foundations we share with other members of our tribe. If he’s right, then we can only explain our interpretation of facts to members of other tribes in ways that resonate with the moral foundations upon which they rely. And to do that, we must first acknowledge and understand them. This is what makes meaningful communication and reconciliation possible.

On balance, Ben Shapiro has been good for American political discourse. At his best, he can be a force for intellectual honesty, integrity, and even open-mindedness in our culture. Were he also to become a force for empathy and understanding he could be great.