Activism

Against the Politicisation of Museums

Activists wanted museums to pivot away from historic collections and towards their audiences, focusing more on excluded groups.

“Museums,” declares Jillian Steinhauer in a recent OpEd for the Art Newspaper, “have a duty to be political.” A lot of her colleagues agree. It’s not enough for museums to entertain, inspire, and educate; they must change the world, too. Needless to say, ‘Make America Great Again’ isn’t what they mean. Worcester Art Museum calls out slave owners in labels on historic portraits. “Honestly, the catalyst for the project was the 2016 Presidential election,” curator Elizabeth Athens explained to Hyperallergic. Queens Museum closed for Trump’s inauguration and held a protest sign-making workshop instead, explaining that, “at a time when the status quo in the US is government-sanctioned racism and xenophobia, it is all the more urgent that museums acknowledge their political histories and adopt stances on contemporary issues.”

Radical criticism of museums has a pedigree. Pierre Bourdieu thought museums were places for elites to develop and flaunt their ‘cultural capital,’ a way of distinguishing themselves from hoi polloi. In his 1979 book Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste, Bordeau defined the museum in the tortured prose of radical social theory as:

[A] consecrated building presenting objects withheld from private appropriation and predisposed by economic neutralization to undergo the ‘neutralization’ defining the ‘pure’ gaze, is opposed to the commercial art gallery which, like other luxury emporia (‘boutiques’, antique shops etc.) offers objects which may be contemplated but also bought, just as the ‘pure’ aesthetic dispositions of the dominated fractions of the dominant class, especially teachers, who are strongly over-represented in museums, are opposed to those of the ‘happy few’ in the dominance fractions who have the means of materially appropriating works of art.

The middle class might not be able to afford to buy art, but museums give them a place to develop and flaunt their cultural superiority. They can ‘symbolically’ appropriate culture by liking different things in different ways.

Bourdieu is identifying a new sphere of inequality in our differential ability to appreciate culture. His influential acolytes argued that museums were too posh, too white, and too masculine. Activists wanted museums to pivot away from historic collections and towards their audiences, focusing more on excluded groups. Despite a generation of critical museology, and decades of diversity targets, museum audiences remain stubbornly elite. It’s getting harder to blame stick-in-the-mud curators, because they were ousted long ago. Museums are run by people schooled in the political monoculture of the humanities, and some are determined to impose the same intolerant norms on museum visitors.

The new curatorial activism builds on the heritage of critical museology, but also reflects its failure. Rather than adapting museums to serve a wider audience, they argue that museums should actively shape their audiences by impressing on them the gospel of social justice. It devalues collections and condescends to visitors.

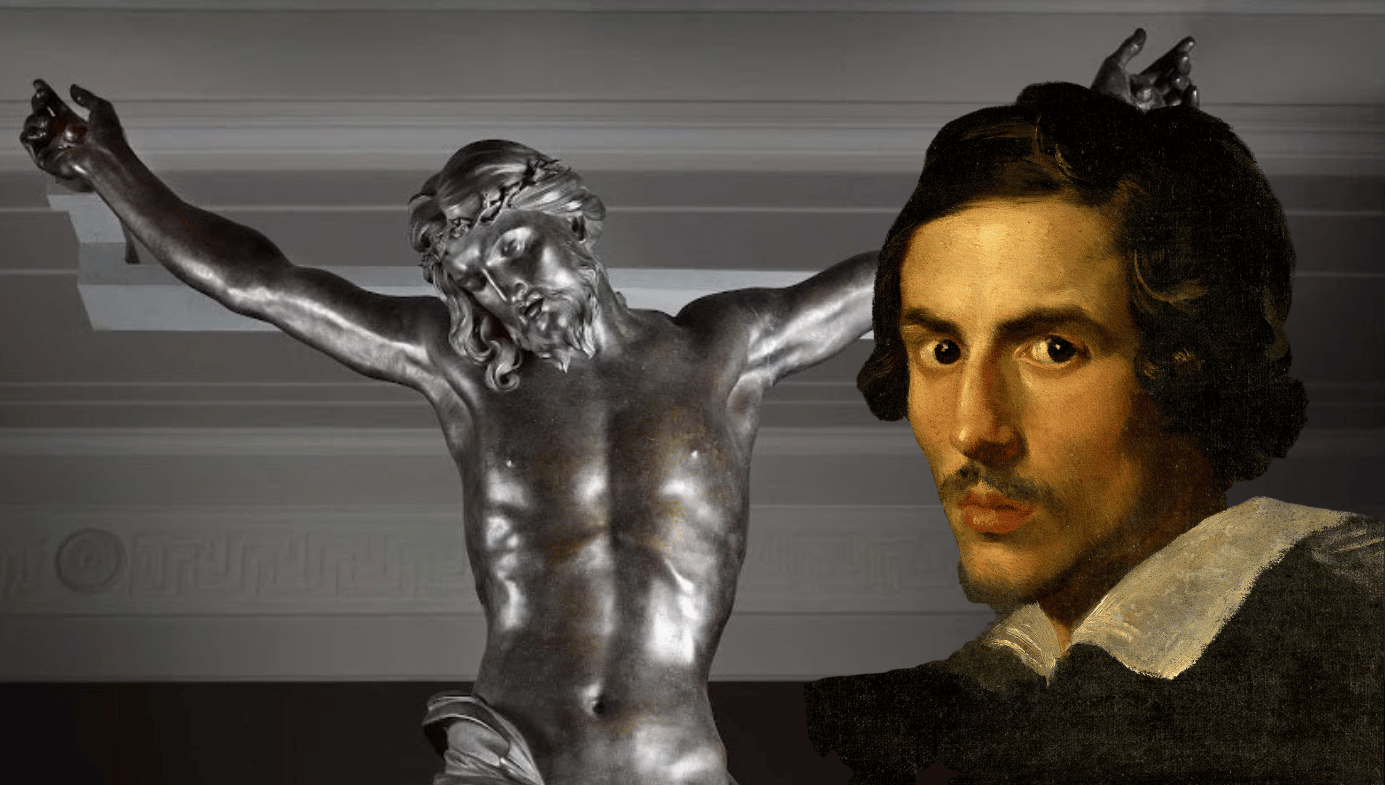

At the end of January, Manchester Art Gallery removed a Victorian picture of ‘Hylas and the Nymphs’ to prompt discussion: “How can we talk about the collection in ways that are relevant in the 21st century?” they asked. Artist Sonia Boyce said she wanted to ‘prompt debate,’ and taking the picture down tells us that the debate is more important than the art. “The gallery exists in a world full of intertwined issues of gender, race, sexuality and class, which affect us all. How could artworks speak in more contemporary, relevant ways?” the museum mused. This provocatively stupid stunt attracted global attention, but fewer people have noticed that one of its greatest masterpieces, a beautiful crucifixion by an associate of Duccio, has also been languishing in storage. It was bought at great expense following a national fundraising campaign led by former director—and great connoisseur—Sir Timothy Clifford. The new managers are excited by political debate, but don’t even display their best pictures.

Tate Britain is now showing an exhibition of British figurative art, ‘All Too Human.’ The explanatory wall text tells us that, “Women’s lives and stories have often been overlooked in art as a historically male-dominated activity … As viewers we are drawn into and become complicit in an unruly world shaped by patriarchal power.” The idea that we become ‘complicit’ simply by looking at a picture is extraordinary, yet this can be asserted without question. And as art history, it overlooks the Renaissance obsession with the life of the Virgin and female saints, and the entire history of genre painting and portraiture. Across town the National Gallery is stuffed with pictures showing that women’s lives and stories have been central to the history of art. The political narrative obliterates the historical record. The final room is only women artists, who “investigate and stretch stereotypical views on femininity, masculinity, race and the many other categories that define and constrain our identity.” These dreary words don’t explain or inspire. They petulantly assert a narrative of victimhood that is orthodox in some academic disciplines, but perplexing to the rest of us.

That’s why I’m fearful of the popular idea that the row about Confederate monuments can be resolved by putting them in museums. The argument is that museums will be able to contextualise them, but can we trust museums to do that? Many of the statues were cheaply mass-produced and have no particular artistic or historic value. The only reason to put them in museums is to tell a story about them. In an article for the American Alliance for Museums, Elizabeth Merritt worries that museums “need to critically examine their own histories of exclusion and any continued complicities in what they monumentalize before they earn the right to properly contextualize racist memorials.” The word ‘properly’ carries a lot of weight. It’s clear what she means when she says “we must recognize our own histories of complicity in the centering of white, male, hetero-normative heritages and the celebration of icons of white supremacy in our centuries of collection and display.” Check your privilege, museum goers!

Ironically the audience is sidelined in the race to be Woke. Polls show that only around a quarter to a third of Americans favour relocating Confederate monuments, and in one poll only half of black people supported removal. Elizabeth Merritt’s angst is not shared by the community she serves. In the New York Times article entitled “Decolonizing the Art Museum,” Olga Viso asks how museums can “reconceive their missions … as more diverse audiences demand a voice.” But it is the conformist curators and activists rather than ‘diverse audiences’ who are demanding change. The audiences are just the object of curators’ political activism; they must be made to recognise their victimhood or complicity. Like the old conservative ‘Moral Majority’ crusaders, they seek out objects of outrage to vent their fury but don’t represent a real majority. Colonising the museum world and enforcing Correct Thinking is a way of evading the hard work of convincing a wider public in the political sphere.

Overt political partisanship remains rare and the most outspoken curators face resistance. There was a righteous outcry against Manchester Art Gallery. Laura Raicovich, the director of Queens museum who hosted the protest sign-making event was fired for misleading the board over her refusal to host an event for the Israeli embassy. Helen Molesworth, a prominent critic of ‘white male privilege’ in the art world, was fired as chief curator at MOCA Los Angeles. But recent op-eds show that people are limbering up for a fight. It’s true that museums cannot be neutral. Nothing interesting is neutral. But that’s not an excuse for asserting partisan control, turning museums into instruments for engineering a right-thinking progressive citizenry. It won’t work. It will alienate patrons and provoke a backlash. Do we want left wing museums and separate right-wing museums, or museums contested between radical and conservative curators?

We risk losing sight of the inspiring brilliance of museums. Whether it’s a neolithic axe head or a Raphael altarpiece, objects in museums give us a sense of connection with human history. From the towering heights of human civilization to mundane details of our ancestors’ lives, museums delight and inspire. Curators play a vital role in selecting, displaying and interpreting. But we don’t go to museums to be indoctrinated. It would be tragic to lose our sense of wonder to the culture wars.