History

Why We Say 'Islamism' and Why We Should Stop

‘Islamism’ seems to offer the possibility of distinguishing Islam, the religion of over a billion Muslims, from the actions and ideas of violent movements that act in its name.

‘Islamism’ is a word that refuses to die. Conceived by a group of French academics who have since disavowed their creation, it has been criticized by many on the Left and the Right. Yet it still appears in scholarship, the media, and political discussions, jostled alongside terms like ‘fundamentalism,’ ‘political Islam,’ ‘radicalism,’ etc., ‘Islamism’ seems to offer the possibility of distinguishing Islam, the religion of over a billion Muslims, from the actions and ideas of violent movements that act in its name. But this distinction, however desirable, is untenable. The scholars who invented the term decades ago are today the first to regret its use.

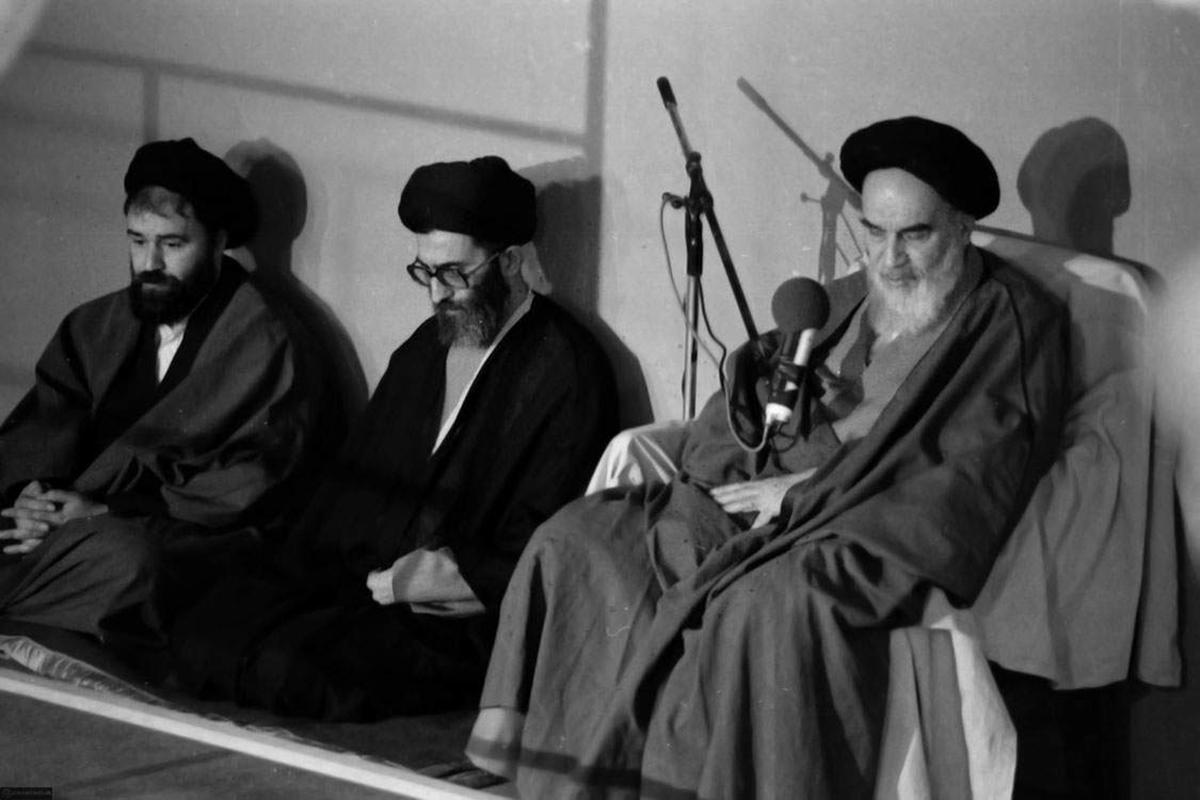

The Iranian Revolution of 1979, greeted with optimism by intellectuals such as Michel Foucault, chilled more critical observers in France. A rising generation of anthropologists, sociologists, and other scholars noticed that the new regime in Tehran was not alone in its fusion of modern mass politics and Islam. Doctoral students and junior professors researching the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, revivalist groups in North Africa, and anti-Communist rebels in Afghanistan searched for a word that would allow them to connect and compare these disparate phenomena. In a series of articles that appeared in 1980 for the French magazine Esprit (known for its support for Soviet dissidents like Alexander Solzhenitsyn), a young anthropologist specializing in North Africa, Jean-François Clément, proposed the term ‘Islamism,’ drawing an obsolete synonym for ‘Islam’ out of the dictionary and remaking its meaning.

Clément chided French journalists who described the ayatollah Khomeini, leader of the Iranian Revolution, as a medieval fanatic. He likewise criticized scholars who characterized the ayatollah, the Muslim Brothers, or Afghan mujahideen as intégristes, the French equivalent of fundamentalists. These labels, Clément warned, offered false reassurance. Fundamentalist religious groups in the United States and Europe were minorities who self-consciously opposed modernity, communities that could be dismissed as anachronisms. The new political movements across the Islamic world, Clément insisted, were different. They aimed to create a powerful, modern Islamic state. The term ‘Islamism,’ as it was first understood, focused attention on the fact that violent Islamic political movements were not vanishing spectres from the distant past but powerful forces at home in the modern world.

The word quickly spread. Over the following years, ‘Islamism’ would filter into French media and politics, and into the English-speaking world. There were ever more Islamic political movements to talk about, and their actions were ever more worrying from the perspective of Western societies. The appeal of the terms ‘Islamism’ and ‘Islamist’ to journalists and policy-makers struggling to understand a dangerous world is obvious. The words offered a way to describe, and to condemn, violence motivated by Islamic doctrines without appearing to criticize Islam itself. One can excoriate Islamism — a scholarly abstraction with which hardly any individuals or groups identify — while expressing respect for Islam and Muslims. In fact, French laws against ‘inciting hatred’ make it risky not to draw such distinctions. Charlie Hebdo, Michel Houellebecq, and Brigitte Bardot have all faced law suits or criminal charges for their comments about Islam.

Clever antisemites in France, facing the same legal restrictions on speech ‘inciting hatred’ against Jews, have come up with their own distinction. Groups such as the Anti-Zionist Party attack ‘Zionism,’ which they allege is not just a pro-Israel political tendency, but a shadowy conspiracy whose members control the world’s banks and media. As the term ‘Islamism’ spread, Muslim advocacy and anti-racist organizations in France and elsewhere began to suspect that a similar trick was being pulled on them. Critics of Islam, they allege, condemn Islamism in order to give themselves plausible cover while they pursue their real target.

This debate has echoes in the United States. The Council on American-Islamic Relations has long called on the media not to use ‘Islamism,’ which it says often means “Muslims we don’t like.” CAIR has itself been accused by critics of being an Islamist organization (and even labeled a terrorist group by the United Arab Emirates) and its arguments against the term are perhaps self-serving. Nevertheless, it has a point, and it is one that right-wing media outlets like Breitbart miss when they criticize CAIR’s stance. There are, in fact, no objective criteria for distinguishing between (bad) political expressions of Islam and (good) non-political expressions of Islam — or for arguing that the former is not really Islam at all. Religions are not just expressions of individual belief; they are claims about how society should be organized, and they are institutions that organize it. Religion is political — and Islam, in which theology and law go hand-in-hand, perhaps especially so.

The French scholars who popularized ‘Islamism’ realized for themselves the futility of trying to distinguish a specifically political form of Islam from Islam itself. Clément now regrets the term he created. He wishes that he had come up with a word that “had no relationship with Islam,” some term that the media and politicians could not have used as a euphemism for Islam or a cover for anti-Muslim sentiment. Of course, even words that have no semantic reference to Islam, like ‘terrorism’ or ‘radicalism,’ are associated with Islam in the public mind, and for obvious reasons — a fact that has led news organizations like Al Jazeera and the BBC to avoid even these terms.

Other French thinkers who brought ‘Islamism’ into common use in the 1980s, such as Olivier Roy and Gilles Kepel, found more serious problems with the term. By the 1990s, Roy and Kepel, now France’s pre-eminent experts on Islam (and bitter rivals) had noticed a paradox. Islamic political movements, when they came to power, failed to achieve their utopian goals and — notably in Iran and Afghanistan — devolved into uninspiring authoritarian states. Yet the intensification of religious fervor, led by ostensibly non-political Salafist and Tabligh groups, continued unabated across the Islamic world, including among immigrant communities in Europe.

‘That Ignoramus’: 2 French Scholars of Radical Islam [Kepel & Roy] Turn Bitter Rivals by Adam Nossiter https://t.co/BysZ5tMW3T

— Martin Kramer (@Martin_Kramer) July 13, 2016

For Roy this was a sign that Islamism was over; in 1999, he buried the notion of Islamism and claimed that revivalist Islamic organizations in France were part of a new phenomenon, ‘post-Islamism,’ which he optimistically predicted would create “its own space of secularism.” True to this logic, Roy now argues that the recent wave of Islamic terrorism in France is not an expression of long-running conflict rooted in the political movements formerly known as Islamist, or the result of French Muslims falling under the sway of radical (albeit officially non-political) Islamic groups. Rather it is “a generation’s nihilistic revolt”: alienated youth who use Islam as a pretext for their aimless violence. Like Roy, Kepel had also predicted the “decline of Islamism” as a political movement in the late 90s. Today, he argues that he and others who developed Islamism as a concept failed to understand that the difference between political and non-political religious movements is vague, if not illusory. Supposedly post-Islamist religious groups whose leaders eschew formal politics are “in fact political: they provide the social basis on which a political reality will be built.” Those who desire the “re-Islamization of society,” by whatever means, are really positing a political goal, and they inspire both political movements and violent radicals. Kepel thus rejects Roy’s explanation for Islamic terrorism and communitarian tensions in France, which he sees as particularly troubling expressions of a vast religious movement.

The scholars who created the concept of Islamism over thirty years ago now reject it. While each has reasons of his own, rooted in the specific concerns of French scholarship and politics, their essential problem is one that intellectuals and policy-makers throughout the world share. It appears critical for academia, media, and governments to distinguish Islamic movements and individuals that pose a threat from Muslims in general. The distinction, at first glance, may seem easy and common-sensical, a matter of identifying a small minority. Yet as scholars, journalists and politicians seek to distinguish this minority from the majority of the world’s Muslims, they also feel the need for a label that can link the ideologically and geographically diverse Islamic groups that pose a threat to the West. The two aims, unfortunately, are at cross-purposes. The intellectual collapse of Islamism reveals that criteria common to various dangerous movements, such as politicization or religiosity, are also shared by far larger numbers of Muslims who have nothing to do with them. Concepts like Islamism seem to offer an objective solution to an agonizing dilemma, but they can do no more than disguise it.