Security

Balancing Threat in the Middle East

What are the sources of Iranian and Saudi foreign policy and what prudent options there are for the West to adopt?

Last month, the BBC asked will Saudi Arabia and Iran go to war? The question is redundant as they are already at war. Iranians are currently engaged in propping up a Shi’ite crescent from Iraq to Syria. The Saudis are blockading Qatar, threatening Lebanon, and bombing Yemen back to the Stone Age. To quote the Prussian general and the sage of warfare, Carl von Clausewitz, “War is merely continuation of state policy by other means.” By that definition, the Saudis and Iranians are already engaged in a vicious struggle for control of the Middle East in Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, Palestine, and Yemen.

So what is prompting this hegemonic aspiration from both sides? What are the sources of Iranian and Saudi foreign policy and what prudent options there are for the West to adopt? The prudent question for the West is not whether there will be a land war as such, but what grand strategy the West should follow.

Arab-Persian Rivalry or Shia-Sunni Differences?

Historically, Persia was a rightful hegemon of the region, since the time of Hellenic Greece and Alexander the Great. During the Middle Ages, it was one of the greatest moderate Islamic empires of Asia, alongside the Ottomans and Mughals, which made immense cultural contributions to the world.

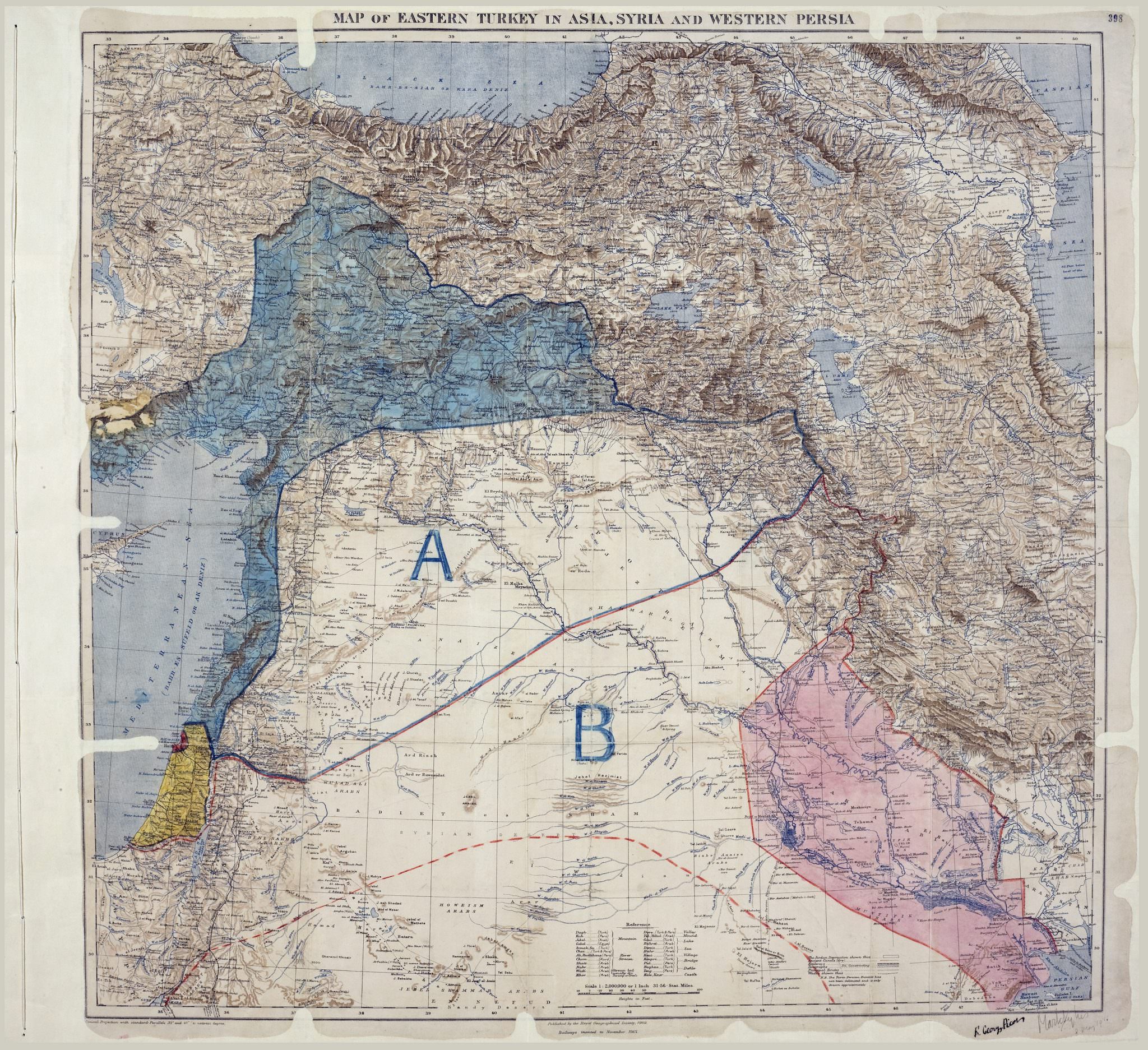

Saudi Arabia, on the other hand, like most other modern Arab states, traces its roots to colonial powers. While the British Empire had fixed interests in India and Egypt, the foundation of the Anglo–Iranian Oil Corporation in Persia in 1908, and the subsequent discovery of oil in Iraq made the stretch of land from the Euphrates to Aden extremely geopolitically significant. By 1918, both Britain and the United States realized that the future of warfare and Anglo–American interests would be linked to oil. So Persia was pivotal for stability in the region. Arab lands in Yemen and Saudi Arabia, however, were less important as resources but more significant as strategic chokepoints.

With the fall of the Shah of Iran in 1979, the delicate balance in the Middle East was lost. The Saudis had always considered themselves as the guardian of theoretical Islam, but with the Shi’ite Islamic theocratic republic in Iran directly threatening monarchic Saudi rule, the rivalry, which was supposed to be purely geopolitical, took on a religious overtone. Cold War dynamics also led to the rise of Saudi importance, which in turn led to the proliferation of an extreme form of Sunni Wahhabism from Pakistan to Tunisia.

It also led to one of the most Sophoclean ironies in history. Iran, historically a highly cultured and comparatively liberal society, unfortunately led by a string of theocrat Ayatollahs, became entangled in a geopolitical rivalry with a society that has traditionally been tribal and orthodox but also led by a Western-educated monarchy. Walk around the streets of Tehran and you will find men on their way to shisha bars as well as women wisely avoiding the religious police while wearing sunglasses, high heels, and hijabs pulled back so far they look like they are worn for the style factor, rather than for modesty.

The lifestyle in Iran is incongruent with the daily rhetorical threats of the obliteration of the Jewish state coming from their rulers. Saudi princes, on the other hand, cooperate with Israel daily with regards to Hamas and Hezbollah, but carrying a rosary or a bottle of wine openly through the streets will result in very unpleasant consequences. These are merely facts. The cultures of Iran and Saudi Arabia are vastly different and are far more complicated than the simplistic portrayals we are shown in the media.

‘Balance of Threat’ in the Middle East?

It is important at this stage to remember Stephen Walt’s Balance of Threat theory, which suggests, in crude terms, that states do not simply balance against another power but against perceived threats. Measurable factors, such as the aggregate power of a state, which is the combination of total military and economic power; geographical proximity of the threat; offensive military power; and offensive intentions all affect state behavior. In simple combinations, caeteris paribus, an increase in aggregate power, higher offensive intention, and closer geographic proximity leads to an increased chance of conflict. If you add a nearby revolution or foreign interventions and proxy wars in client states, the result almost invariably leads to what we call a “security dilemma,” which signals the possibility of a full-scale conflict spiral. In the case of Iran and Saudi Arabia, with a proxy war in Syria and revolution in Yemen, almost all the factors mentioned above are present.

Western foreign policy in the Middle East has also been incoherent. British foreign policy had supported the Ottoman Turks against the Russians since the 16th century, which culminated in the Crimean War, until Britain eventually helped the Arabs overthrow the Ottomans. This falls perfectly in line with the British grand strategy of over five hundred years, namely, supporting the weaker of the two foes in what is known as triangular balancing, as explained by Churchill. (This was a similar tactic that also saw Britain balance against the bigger of the two threats by supporting the smaller one.) Some cases in point are Britain’s support of the Dutch against the Spanish, Prussia against Napoleonic hegemony, and France against both the Kaiser and Hitler. This is a common realist geopolitical logic, and Kissinger wrote about following the same principle in a détente with Maoist China against the Soviets’ hegemonic aspirations.

This foreign policy principle, however, has been bafflingly inconsistent in the Middle East. Logically, if supporting the smaller of the two quarreling powers is the most cynically realist thing to do, then the West, by definition, should align itself with the Shi’ites, who are demographically and militarily weaker than the Sunnis, and who would balance out the ascending Saudi hegemonic aspiration in the Middle East. Petro-states are never reliable allies, and Saudi Arabia is also declining in geopolitical importance for the West, as recent research has suggested.

Prominent academic realists also warned against the Iraq invasion and the idea of liberal democracy promotion, predicting that it would give rise to an Iranian counter push for hegemony, which would result in Saudis feeling threatened and a consequent security dilemma spiral. Unfortunately, foreign policy based on narrow, strictly geostrategic interest has been out of fashion in the current London–DC consensus since 1993. The result is that we now have an Iranian rush to have a land bridge from Tehran to Tartus, along with vicious Saudi backlash in Yemen and Lebanon.

The most prudent foreign policy for the UK and U.S. at this stage would be a conservative bias for inertia and playing for time, acting as an offshore balancer, letting regional powers decide the future of the region, and physically cordoning off and staying out of this Middle Eastern version of the Thirty Years’ War. Napoleon said that when your adversaries are determined to commit mistakes, it is imperative to let them continue. Given that there are no Western “allies” in the Middle East and no narrow geostrategic interest for the West—other than keeping the sea routes open—and given that there is no existential risk that directly threatens European and American landmass, the prudent realist foreign policy would be to stay out of any conflict and let regional powers duke it out until stability is achieved in the region. Yet trends of the last quarter century of idealistic Western foreign policy suggest that this simple solution is unlikely to happen.