Human Rights

Islamic Feminism's Depressing Future

Muslim women are fighting stridently within their communities, but their fight doesn’t tread the same path as secular Western feminism.

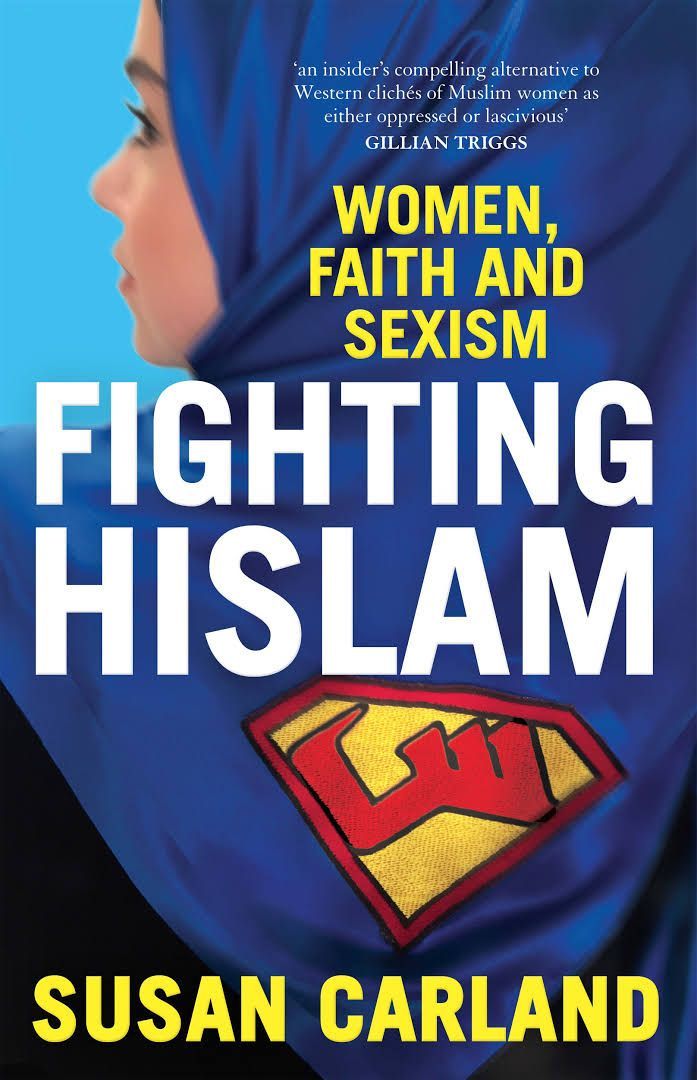

A review of Women, Faith and Sexism: Fighting Hislam, by Susan Carland. Melbourne University Press (May, 2017) 266 pages.

Dr. Susan Carland is an important public figure in the Australian landscape, especially at a time of heightened cultural intolerance. As an academic, a Muslim convert, and the wife of the most widely recognized Muslim in Australia today – journalist and TV presented Waleed Aly – Carland often finds herself in the role of the defender of Islamic faith in Australia. She has personally experienced two different (and currently clashing) cultures closely, has had the privilege of examining them from a social theory perspective, and is blessed with eloquence and charm. Who better to explain what is going on?

On the one hand, we keep hearing about and seeing evidence of the unequal treatment of women within Muslim communities the world over. On the other, we find that Muslim women are among the staunchest defenders of Islamic faith and community. So how are we to reconcile these two realities? And to what extent are regressive practices coded into Islamic religious texts?

Carland’s recently published book Women, Faith and Sexism: Fighting Hislam is an attempt to grapple with these vexing questions – a condensed, reader-friendly version of her Ph.D. thesis on feminism within the West’s Muslim communities. For her thesis, Carland interviewed 23 Muslim women who are fighting sexism and misogyny within Muslim communities in Australia and the United States. These interviewees include theologians, academics, journalists, bloggers, and activists. The book discusses their work, why they felt it was needed, the challenges they face, what role their faith plays in the fight, and who supports them.

The book makes no bones about the fact that sexism and misogyny are rampant within Muslim communities. However, it challenges the notion that Muslim women are simply passive victims. Carland argues that Muslim women are fighting stridently within their communities, but that their fight doesn’t tread the same path as secular Western feminism. Instead, theirs is a feminism born of and rooted in Islam. If anything, Carland argues, Western critics of Islamic practices have only made the work of Muslim feminists more difficult lest they provide fodder for anti-Muslim bigots. While such points are arguably valid from the point of view of Muslim women, they raise larger and more troubling questions for the secular societies in which Muslims and non-Muslims co-exist.

Carland argues that Muslim women’s emancipation cannot be achieved through the rejection of Islam. Any approach that requires them to choose between their Muslim identity and faith and their own empowerment will fail because it asks too much of them. Nearly all the women Carland spoke to look upon religion as an important means of advancing women’s rights. Liberal and reformist female theologians are reinterpreting Qur’anic teachings from a woman’s perspective, and journalists, bloggers, and activists are using these re-interpretations to awaken Muslim women to their rights.

However, this is not just an exercise in pragmatism. The women Carland spoke to reinterpret Qur’anic teachings because they see the current patriarchal interpretations as un-Islamic and a perversion of their faith. They consider it their divine duty to reinstate the egalitarian spirit that many of them feel is inherent in their faith but absent in patriarchal interpretations. It is easy to see that using Islamic teachings to bring about change in patriarchal practices makes sense. To ask women to give up their faith, history, culture, and community and throw themselves into the unknown in pursuit of their rights is a tall order. In fact, as the book says, it can have the opposite effect of hardening the shell of their faith. It is easier for them, instead, to find their rights within their existing religious framework.

But two larger questions arise from this approach.

First, if the teachings of the Qur’an are subject to such widely divergent readings, who is to say that one interpretation is more valid than the next? Or that women will necessarily come up with progressive interpretations of the text? To take one tragi-comic example, Muslim women in the Australian chapter of Islamist organisation Hizb ut-Tahrir are suggesting that the Qur’an allows men to hit women so long as it doesn’t hurt. Moreover, novel feminist interpretations may themselves become outdated with time, which means that the issue of women’s rights is simply deferred and not comprehensively addressed.

Perhaps the problem is that, while Carland repeatedly insists in her book that radical new interpretations of the Qur’an are revolutionizing Muslim communities, she doesn’t offer a single example of what these re-interpretations actually constitute in practice. Nor does she reference the specific recommendations of any of the books, blogs, or magazines that she claims are offering radical new feminist interpretations of Qur’anic teachings. So it is left unclear what constitutes ‘equality’ between men and women in the light of these reinterpretations.

The book gives us at least one reason not to take Carland’s understanding of “radical” at face value. Early in the book, she speaks of Aisha, wife of Prophet Mohammed, and her renowned rulings. However, the example she offers of such a ruling is of Aisha criticizing a man for comparing women to animals such a dogs and cats. This is, to put it mildly, a pretty low benchmark for what constitutes a feminist ruling under Qur’anic law.

Second, a desire for religious guidance when considering complex ethical and religious questions such as same-sex marriage, euthanasia, and even divorce and inheritance is perhaps at least somewhat understandable. But surely straightforward questions such as “Does my husband have the right to hit me?” should not be subject to the convoluted acrobatics of Qur’anic interpretation. Why is it that Muslim women will only believe that a life free from sexual and physical violence is their right if they are able to prove that the Qur’an says so? And what if it doesn’t or they are unable to prove that it does? Across the world, women have arrived at answers to such basic questions independent of religious edicts. Are we to understand that Muslim women are unable to do the same? Apparently so.

In support of her argument, Carland quotes the American scholar Kecia Ali saying that, for most Muslims, “whether a particular belief or practice is acceptable” depends on “whether or not it is legitimately ‘Islamic'” This, she says, is true of Muslims everywhere, irrespective of whether they consider themselves moderate or fundamentalist, progressive or conservative. “Even many of those who do not base their personal conduct or ideals on normative Islam believe, as a matter of strategy, that in order for social change to achieve wide acceptance among Muslims they must be convincingly presented as compatible with Islam.”

So where does that leave non-Muslims anxious to promote a universalist understanding of women’s rights? These include government spokespersons, electoral representatives, and other community members and activists, to mention but a few. It seems they have two options. They can either leave all feminist activism to Muslim theologians and clerics in the hope that they will do the job for them. Or they can educate themselves in the countless Qur’anic interpretations, select an interpretation that most suits the argument they want to make, and enter into a theological debate with conservatives and fundamentalists in the hope that their case will eventually prevail. And for what? To convince Muslims on issues that most of us have established are matters of natural justice.

This goes to the heart of the discomfort many non-Muslims feel when confronted by Islamic cultures. They wonder whether a conversation is possible with Muslim communities when, no matter how objectively rational or valid a point may be, it is held to have no legitimacy unless it can be substantiated by the Qur’an and its myriad interpretations.

Carland says Muslim feminists in the West find themselves in a double bind. Speaking out against what they see as injustices within the community provides ‘Islamophobes’ with ammunition. This makes them the objects of resentment within their own communities and, consequently, makes their reformist task harder. So, when non-Muslims engage with Muslim women, the interviewees say they are unable to speak their minds. The parameters of discussion, they felt, were set by the prejudices and preoccupations of the majority and not by what is relevant to Muslims and their communities.

This is indeed a tough a position to be in. And, as Carland points out, it is made harder by the fact that often it is Muslim women, easily identifiable through their Hijabs and burqas, who face the brunt of anti-Muslim abuse (often in form of physical or verbal abuse on streets). So in speaking out, Muslim women have to accept that they risk, at least in the short term, making their own lives and the lives of their Muslim sisters more insecure. Nevertheless, most interviewees said they do continue to speak out as they have decided that this is more important than concerns about community image or anti-Muslim prejudice. For this courageous commitment to principle, they deserve our respect. But Carland doesn’t make clear how she thinks non-Muslims in the West should engage with Muslims with respect to regressive beliefs and practices.

Sexism and misogyny are universal problems. However, the nature and extent of these problems within Muslim communities is particularly severe. No other community in the West focuses with quite the same intensity on what women wear, how they ought to conduct themselves in public and private, or insist on the complete separation of male and female spaces. For perspective, consider an instance described by Carland herself in which the women’s prayer room in a Washington DC mosque would be chained from the outside while women prayed inside. How do we discuss such practices without drawing attention to their peculiarly pernicious quality? And how exactly are non-Muslims to respond to the fact that Muslim men and women require the minutiae of their lives to be guided by labyrinthine Islamic edicts? It may suit Muslim men and women but it also renders the community opaque to non-Muslims and cultural opacity will always provoke fear in outsiders.

Carland argues that sexism and misogyny within Muslim communities must not be an excuse for prejudice on the part of non-Muslims. But she also insists that any discussion of these issues with Muslims must be filtered through an Islamic religious lens. So, non-Muslims can neither have a positive dialogue about women’s rights on an equal footing with Muslims unless it is done from a theological perspective, nor can they allow religious opacity to colour their engagement with and understanding of Muslim communities. This raises the bar for any meaningful dialogue so high that it will inevitably result in failure and increased distrust on both sides. No wonder Muslims and non-Muslims both feel suffocated by the interaction.

If we follow Carland’s argument to its logical conclusion, the only option we are left with is for Muslims and non-Muslims to ignore each other until Muslims find an interpretation of the Qur’an that meets secular standards in matters of gender and family. In the meantime, everyone must keep up a tight smile when we encounter one another in public and privately hope that our lives don’t intersect through love, romance, marriage, or our children. That sounds like a depressing future.