Education

Should We “Stop Equating ‘Science’ With Truth”?

The message that liberates women is not: men and women are the same, and anyone who tells you different is oppressing you.

Actually: no.

In the modern world, there are ever fewer reasons to maintain the distinct roles of men and women, which evolved over millions of years. But to imagine that we are not living with that inheritance is to reject not just science, but all forms of logic and reason.

The message that liberates women is not: men and women are the same, and anyone who tells you different is oppressing you. The message that liberates women is: men and women are different. (And in fact, everyone who is intellectually honest knows this—see Geoffrey Miller’s excellent point regarding the central inconsistency in the arguments being presented by the control-left.) And not only are men and women different at a population level, but our distinct strengths and interests allow for greater possibility of emergence in collaboration, in problem-solving, and in progress, than if we work in echo chambers that look and think exactly like ourselves. Shutting down dissent is a classic authoritarian move, and will not result in less oppression. You will send the dissenters underground, and they will seek truth without you.

Evolutionary biology has been through this, over and over and over again. There are straw men. No, the co-option of science by those with a political agenda does not put the lie to the science that was co-opted. Social Darwinism is not Darwinism. You can put that one to rest. There are pseudo-scientific arguments from the left. Gould and Lewontin, back in 1979, argued, from a Marxist political motivation, that biologists are unduly biased in favor of adaptive explanations, which managed to confuse enough people for long enough that evolutionary biology largely stalled out. And, perhaps most alarming, there are concerns that what is true might be ugly. Those who would impose scientific taboos therefore suggest that it is incumbent on scientists not to ask certain questions, for fear that we reveal the ugly. That, I posit, is what underlies the backlash against Damore’s memo.

To which science and scientists need to respond: the truth is not in and of itself oppressive. To the extent that selection has produced differences between groups, such as differences in interests between men and women, denying the reality of that truth is hardly a legitimate response.

People often imagine that when a biologist argues that a pattern is the product of adaptive evolution, they are justifying that pattern. Philosophers have named this confusion the naturalistic fallacy, in which “what is” is conflated with “what ought to be.” Every good evolutionary biologist knows to dismantle such thinking in their own and their students’ heads as quickly as possible. Only by knowing what is, however, can we have a chance of structuring effective, society-wide responses that might actually change some of what is, when that is desirable.

Evolutionary biology is not ‘splaining, man- or otherwise. In contrast, the control-left and, and more specifically Chanda Prescod-Weinstein in her recent Slate piece, most definitely are.

It's time for scientists to pro-actively start doing better: learn history to avoid making the past's mistakes. https://t.co/GVMGKP8ERp

— Dr. Chanda ?? (@IBJIYONGI) August 9, 2017

Allow me to explain. ‘Splaining is different from explaining. ‘Splaining uses authority rather than logic to make points. By contrast, explaining, as in the way of science, tries to minimize assumptions and black boxes, and return to first principles whenever possible. Authority is not what scientists use to seek truth. Reality doesn’t care about degrees or gravitas. Working with the scientific method, we follow a meandering path, with many wrong turns and dead-ends. The scientific method can be remarkably inefficient, but we tolerate that inefficiency because of what it buys us: Science is self-correcting. Over time, our answers are ever better, and more in line with objective reality.

It is of course true that, in the European tradition of scientific investigation, white men have mostly been the people doing science. And who does the science will affect what questions are asked. But the scientific method, when deployed correctly, protects us from getting biased answers to those questions. More diversity amongst scientists will diversify the questions being asked, but should not alter the answers to those questions.

On Damore’s list of left vs. right biases (which he includes to point out that we need perspectives from both “sides”), he has “humans are inherently cooperative” as a left bias, and “humans are inherently competitive” as a right bias (read his original memo here). In this case, both are true, simultaneously. It doesn’t even really depend on context. Humans are both competitive and cooperative. Imagining one without the other is missing a big part of what it is to be human. Within evolutionary biology, this isn’t controversial. Furthermore, it’s true not just for humans, but for all species that are long-lived, social, and have both long developmental periods (childhoods) and significant generational overlap. It’s true within dolphins, parrots, wolves, chimps, crows, and elephants, to name just a few. Competition for resources—be those resources food, water, mates, habitat, reputation, or something else—is always present. But sociality is inherently cooperative, and sociality has evolved and persisted many, many times, across a diversity of environmental, developmental, and genetic landscapes.

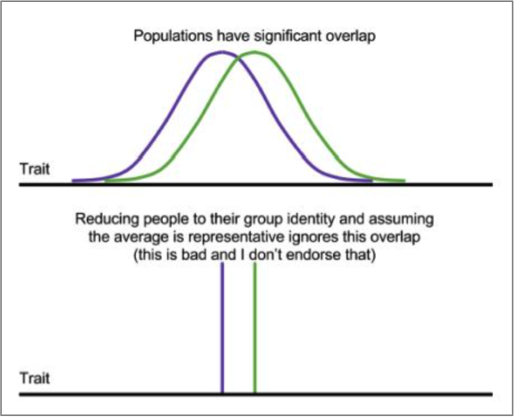

It is also true that a basic misunderstanding of descriptive statistics—of population-level thinking—pervades the backlash to the Google memo. Damore includes this graphic, and writes, “many of these differences are small and there’s significant overlap between men and women, so you can’t say anything about an individual given these population level distributions.”

A binary population (as in the lower graph) is one in which are there are two and only two possible states, and those states themselves are invariant. On and off, ones and zeroes. Binaries exist in the world, but the more complex the system, the more emergent the question. Within science, the farther from physics and math, and the closer towards biology you get, the less binary the landscape is.

A bimodal population, by comparison (as in the upper graph), also has two states, but within each of those states, there is variance. Average individuals from the two states will be different in predictable directions: on average, men are taller than women. But, depending on how far apart those two modes are, individuals who belong to population one may look much more like individuals from population two. This does not put the lie to the category—we all know some very tall women. It reinforces the fact that there is variance in the population. Variance is not a refutation of biology; it is what biology, in the form of selection, acts on to sculpt organisms from noise.

There are male brains and there are female brains. But it’s not a binary. When, as the humans that we are, we categorize things, sometimes there are two possibilities, sometimes three, sometimes more. With mammalian sex, there are two. But identifying that there are two categories is not the same thing as saying that there is no variation within those categories. To imagine that two categories means rigid adherence to one of two ways of being is a failure of population-level thinking. And it is a failure of logic, too.

Some categories have members that are indeed invariant. Everywhere that gold atoms show up in the Universe, they are the same. Each isotope is invariant. But individual horses, and strains of salmonella, and male brains, do not all look alike. They are simultaneously of a type, and distinct within that type.

Male raptors are, on average, smaller than female raptors. Male frogs are, almost universally, more talkative than female frogs. Male humans tend to be stronger, shorter lived, and more interested in “things” than female humans.

Male and female are distinct and real. There are multiple levels on which to ascertain maleness and femaleness, and in some people, chromosomal, phenotypic, and brain sex aren’t the same. But the overwhelming majority of humans have convergence between their chromosomal, phenotypic, and brain sex. When we look at male brains and female brains, there are differences. Recognizing difference is not sexist, or oppressive. It is human.

Perhaps we should, in the spirit of inquiry and logic and the values of the Enlightenment, focus on understanding what is true, rather than throwing temper tantrums because we don’t like what’s true. Then we can begin to disentangle societal gender roles from the rule book of evolutionary sex differences that gave rise to them. Because the deepest truth is that those roles have an ancient and important meaning, which is now desperately out of date.