Art and Culture

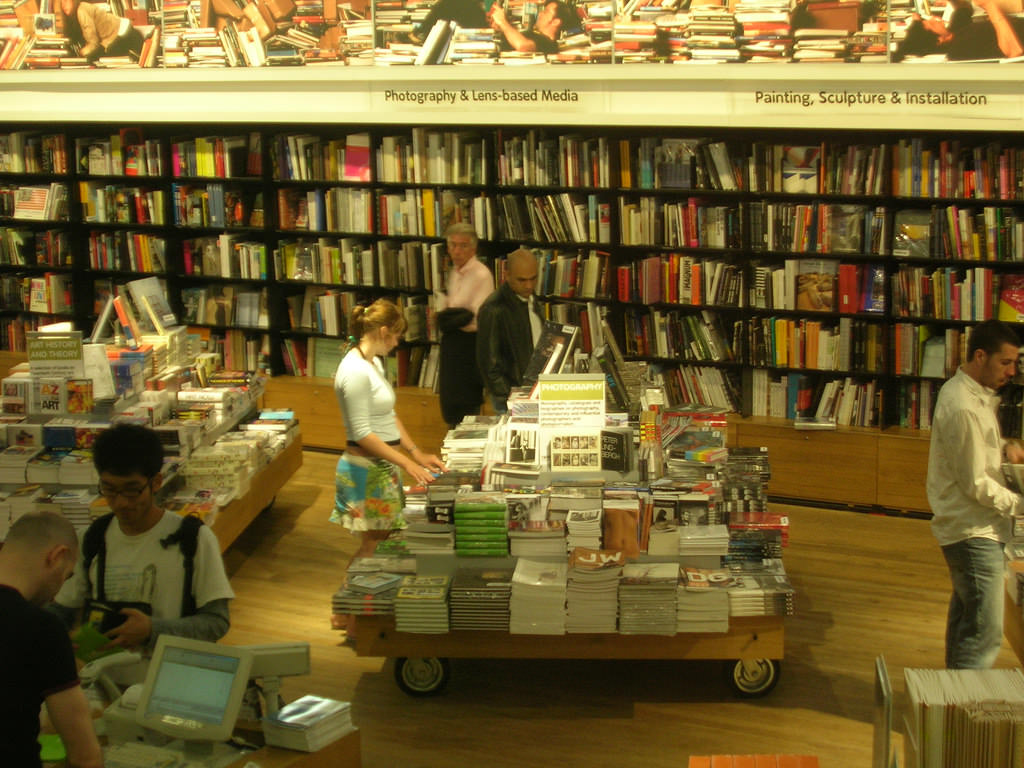

Browsing the Tate Bookshop

The Tate Britain shop is large and there are multiple, unimpeachable shelves of books grouped into themes such as technique, art history.

In the last week of April 2017, a light squall of controversy hit the majestic ship that is Tate, Britain’s state-sponsored multi-gallery institution for British and modern art. Its Director, Nicholas Serota, was moving on (to another public art satrapy, as chair of Arts Council England) and, according to reports, staff were being asked to contribute to a leaving present, despite their low-pay, casualization and the removal of a canteen discount. And not just any leaving present, but a sailing boat. For the staff union, it was proof that Tate management had become divorced from reality.

That same week I visited Tate Britain, Tate’s original neo-classical edifice, just down the Thames from Westminster. Looking for a present for a friend I stopped off in the (extensive) shop. It would be an exaggeration to say that I felt like I’d stumbled into the Socialist Workers Party’s Bookmarks which, after all, is in the more salubrious Bloomsbury. However, the experience was striking enough for me to feel guiltless in at least suggesting the parallel. Several factors clearly influence the Tate bookshop’s stocking choices (not least, one hopes, what sells) but the sheer brazenness of its partisanship, and the mismatch between that and the dragoons of well-heeled retirees rocking up to enjoy David Hockney, suggested something about power and ideology in our cultural institutions and, on reflection, about where that is going wrong.

The Tate Britain shop is large and there are multiple, unimpeachable shelves of books grouped into themes such as technique, art history, and children’s books (there’s also a second outlet more focussed on gifts, though there are plenty of those in the main shop too). Right at the front, though, was a table which, although unmarked, was given over to the theme of ‘Britain’ and behind it the wall shelves started with an extensive section labelled ‘Art Theory’. Regularly punctuating both, however, were volumes with a connection to neither theme, but unified by commitment to a political programme, if a fairly loose one (I don’t want to oversell the idea of a thought-through conspiracy).

Some examples give a flavour of the whole: The WikiLeaks Files, Drone Theory by Grégoire Chamayou, Inequality and the 1% by Danny Dorling; On Anarchism and Occupy, amongst others, by Chomsky, How Did We Get Into This Mess by George Monbiot, a lot of Žižek, Private Island by James Meek, Chavs and The Establishment by Owen Jones, and Tom Mill’s The BBC: Myth of a Public Service, not to mention The Verso Book of Dissent and a whole host of other Verso titles. Some of these are good books (a point I’ll return to) and some no doubt sell, but of necessity each raises the question, why is this here? Or for some Tate Britain visitors—some of those silver-haired Hockney fans, perhaps—the whole set might provoke a different query: I like British art but I lean towards a moderate conservatism, am I unwelcome here?

Though it was books unconnected to the Gallery’s purpose that first struck me, it was then less surprising to find the ‘Art Theory’ section dominated by works promulgating what one might call, in shorthand, a strong programme of social constructionism (that is, the idea that all the concepts we use in thinking are constructed, and constructed by the vested interests of power, rather than mapping what’s really out there). Some of these were directly related to the arts—if rarely visual art per se—others less so. I’ll avoid another long list of examples, but Razmig Keucheyan’s The Left Hemisphere: Mapping Critical Theory Today and Judith Butler’s Gender Trouble give an idea of what was on offer. Emblematic of this trend was Delusions of Gender by the philosopher of science Cordelia Fine.

Several articles published at Quillette have already provided empirical critiques of Fine’s work and its use of rhetorical sleights of hand in the service of an absolutist position on the socially constructed nature of sex differences. My point here is to highlight the symbolic meaning of Fine’s presence in the Tate Britain bookshop, unchallenged by other works on the relevant science (whose presence would be unthinkable, this being an art bookshop). To be interested in art is not just to be a feminist, we are told, but to accept a specific position, a priori, of what ought to be an empirical debate about the respective roles of genetics, biological context, social context, and other factors in sex differences, as observed, experienced and conceptualised. As someone committed to both feminism and empirical argument I find this galling.

So, if I’m troubled by what I found stocked by Tate Britain, what did I think was missing? I’m not arguing that what was needed was some balancing set of conservative authors (with a small c, and in their politics or their art history) in the name of impartiality; though nor would I find such an argument to be necessarily absurd considering the Tate is a public body. Indeed, there were tokenistic gestures in this direction: a single title by the late journalist-provocateur Brian Sewell and inevitable copies of Kenneth Clark’s Civilisation (though nothing else by or about Clark, against a half-shelf devoted to his old sparring partner John Berger).

Rather my point is to note a missed opportunity to focus on the visual arts, the liberal arts, and wider culture—in that order—based on a confidence in their inherent importance, and to do so through a broad-based approach that sees art engaging across the variety of human experience; social, cognitive, experiential, aesthetic and more, and both now and in the past. That might mean some Roger Scruton as well as Guy Debord, but also less easily characterised thinkers like John Gray. It would mean making at least some room for recent work thinking about art through evolution (Denis Dutton as a good starting point) and more for books in the tradition of mainstream aesthetics (Richard Wollheim, Michael Podro) or, at the more popular end, titles like Philp Ball’s Bright Earth On Colour or Philippa Abrahams’ Beneath the Surface linking looking and making. I’m no retailer but it’s just not convincing that only left-academicism sells.

What’s more, some popular art-books were notable by their absence. Take, for example, Alexandra Harris’s Romantic Moderns. This is a few years old now, and may have been stocked by Tate Britain previously. I mention it because I did find Owen Hatherley’s The Ministry of Nostalgia, which includes a knives-out attack on Harris. Both are good books. Whilst Virginia Woolf and T. S. Eliot are hardly unknown, Harris succeeds in resuscitating an important strand in mid-twentieth century intellectual history: it’s awkward but enlightening, for instance, to consider that in 1938 Eliot could advocate a mass return to agronomy. In the process, Harris gives attention to some neglected artists working in print (Gertrude Hermes) and watercolour (Thomas Hennell).

But Hatherley hits his target too. He’s right to take Harris to task for uncritically rehearsing the complaints of dispossessed landowners after 1945 (and could be stronger on how Romantic Moderns acknowledges but hurries over the outright fascism of some of its 1930s subjects, a fascism intimately connected to their ‘romantic modernity’). He’s also right to insist that social progress was central to other strands of modernist action, particularly in architecture and art. What matters here is that in the Tate Britain bookshop this dialogue was a monologue: Hatherley’s book was there to be found; Harris’s was not.

Does this matter? The most common lesson drawn from the electoral shocks of the past year is that Western societies have become collections of self-contained tribes, each one talking past the other. Certainly, any non-committed browser looking over these shelves is going to feel that they speak, or perhaps shout, to someone else. Quite apart from any wider malaise this signifies, it contradicts the Gallery’s stated aim to be ‘welcoming to everyone’. Of course, ‘everyone’ could probably never really mean everyone; but surely it at least includes the ladies and gentlemen of the local Fine Art Society.

The champagne socialist is a perennially easy target, but in part that’s because of the perennial tin-ear that so many within the cultural elite display. And I don’t use ‘elite’ as some catch-all boo-word: I mean, specifically, the most senior administrators and trustees of national institutions, which, of course, takes us back to Serota and his boat. In its self-presentation, its curation, and its bookshop, the Tate can be all radical edge and decentred identity, whilst below-stairs the whole show is being handed over to multinational outsourcing companies. But that kind of contradiction comes at a cost. The cost may be staff sounding off to journalists about management arrogance, or it may be an art culture where institutions and half their audience have no common language, where each lives in a ghetto of self-confirming thought.