Religion

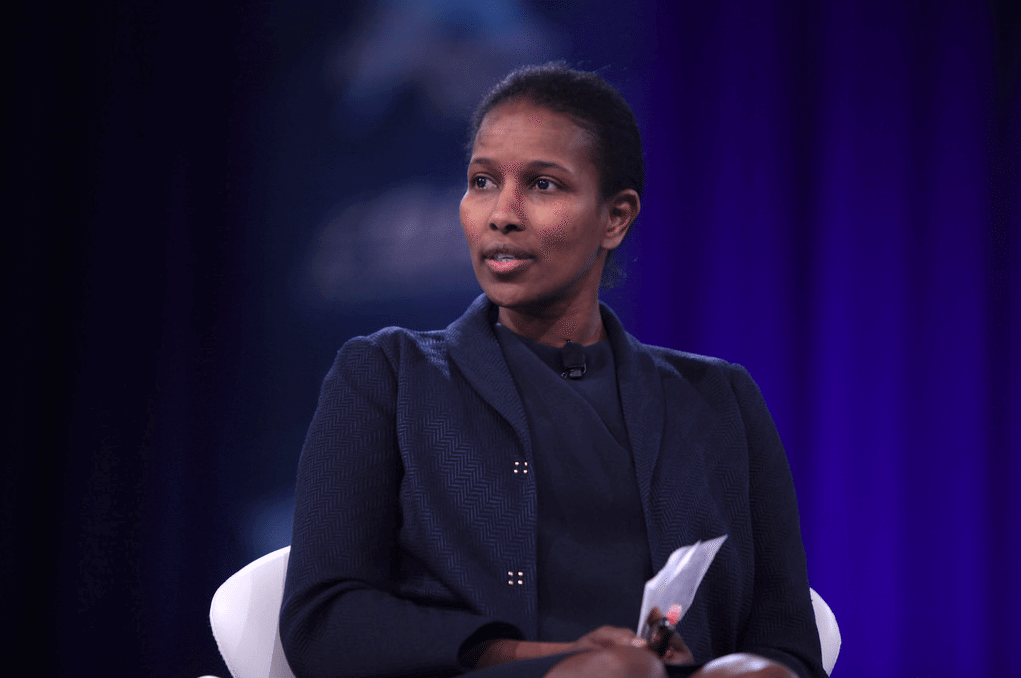

Ayaan Hirsi Ali Explains How To Combat Political Islam

If Hirsi Ali’s critics are tempted to cite statistics minimizing the threat, they will have to explain at what point – after how many more deaths – they will consider it necessary to take action.

What happens when we let fear, muddled thinking, ignorance, and political correctness guide us in confronting a threat to our constitutional freedoms?

We lose everything.

In the United States, our ability to enjoy our rights to liberty and the pursuit of happiness rests largely on the protection the First Amendment accords to freedom of speech and its corollary, the freedom to exercise the religion of our choice – or, of course, to profess no religion at all. It follows, then, that we should both vigorously defend the First Amendment and subject to withering criticism any challenges to it. If we begin dodging or concealing the truth about a threat to free speech, whether out of fear of appearing improper or even of knowing the consequences, we place ourselves at risk of losing our freedom of speech – and everything else we cherish in a democracy.

Speech consists of words. Words and how we use them matter. So, in the annals of self-defeating political inanities, the Obama administration’s term for Islamist terrorism – “violent extremism” – stands out as unusually obfuscatory, semantically unsound, and craven. (The phrase encompasses other kinds of terrorist doctrines as well, but no one can fail to see which one in particular is being addressed.) Originating as ISIS-inspired attacks were starting to hit the United States, it baldly omits their motivating ideology and purports that “extremism” can exist as a rootless, groundless, free-floating phenomenon. The term was so patently contrived to avoid mention of Islam that Republican candidate Donald J. Trump, during last year’s presidential campaign, could appear courageous to many just by saying “Islamic terrorism.” Yet coining the insipid phrase “violent extremism” was just par for the course. Former President Obama’s repeated declarations that the faith in question had nothing to do with all the bombing, beheading, and machete-slashing carried out to the cry of “Allahu Akbar!” looked, at best, cowardly – and at worst, complicit. Hillary Clinton followed Obama’s lead on the matter – all the way to a historic loss at the polls.

The consequences of Obama’s Islam-exculpatory doublespeak linger on – even with Trump in the White House. Though more than two months have passed since Trump’s inauguration, the FBI’s web site still has a page devoted to “violent extremism”; one has to open three links before arriving at a mention of ISIS (which does not, the site informs us with inexplicable canonical certitude, “represent mainstream Islam”). However, as of last year, the FBI had roughly a thousand terrorist investigations ongoing, of which a “significant number” (“hundreds”) involved potential ISIS followers. Knowing this, Obama nevertheless saw fit to muse that, “Americans are more in danger from their own bathtubs than from Islamist terrorists.” The blatantly phony equivalency drawn here belies the obvious, and not just that slipping in the tub is an accident, not an act of coldblooded murder; a bathtub death cannot terrify, or influence public opinion or public policy, whereas terrorism obviously does.

Trump has spoken openly about confronting “the hateful ideology of radical Islam” and claimed to “know more about ISIS than the generals,” but one might be forgiven for suspecting that he has no idea of what he’s talking about. For guidance, however, he should immediately consult Ayaan Hirsi Ali, the Somali-born public intellectual, author, apostate from Islam, and fearless deliverer of uncomfortable truths about her former religion. Regarding Obama’s bathtub babble, she told me in a recent email exchange that “bathtubs don’t go around plotting terrorist attacks. Neither do guns and cars. It’s people. The question is one of intent, and it raises the question of how to prevent deliberate attacks carried out by individuals in the name of an ideology, rather than preventing accidents such as bathtub or car accidents.”

Hirsi Ali is a senior fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School and a research fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution. For the latter, she has just published an comprehensive, thoroughly researched paper, The Challenge of Dawa: Political Islam and How to Counter It. (Dawa is, strictly speaking, Arabic for proselytizing for Islam, but as Hirsi Ali explains, given the troubling specifics of Islamic doctrine, it is “more complex, more sinister, and more far-reaching” than that.) The president and every high-level official in the FBI and the Department of Homeland Security, as well as every member of Congress, should read it. Now.

Hirsi Ali covers her subject in its entirety, substantiating each assertion with footnotes, but here I’ll address only the most salient aspects. Her thesis: the American government’s “narrow focus on Islamist violence had the effect of restricting our options only to tools such as military intervention, electronic surveillance, and the criminal justice system. . . . In focusing only on acts of violence, we have ignored the ideology that justifies, promotes, celebrates, and encourages those acts.”

As should be clear by now, such an approach is not working; the Islamist threat is not diminishing. This, and the Muslim population in the United States looks set to more than double (according to the Pew Research Center), from 2.6 million to 6.2 million by 2030. Hirsi Ali reminds us that abroad the American military campaign against Islamist terrorism has cost us dearly in blood and treasure. Since 2001, the United States has spent more than $3.6 trillion on wars and reconstruction and lost more than five thousand servicemen and women. But Hirsi Ali concentrates mostly on the domestic side of the problem, so I will, too.

The key challenge, as she sees it, comes from Islam’s blending of religion and politics: “Islam implies a constitutional order fundamentally incompatible with the US Constitution and with the ‘constitution of liberty’ that is the foundation of the American way of life. . . . The ultimate goal of dawa is to destroy the political institutions of a free society and replace them with the rule of sharia law.” The Trump administration must decide to confront this ideology; thus, a new “anti-dawa counterstrategy” is needed. It must also understand that ISIS does indeed have more than just “something” to do with Islam. To better understand this, Hirsi Ali, in an email to me, recommended “reading about the early period of the founding of Islam, particularly Muhammad’s period in Medina: the military campaigns, the bodily punishments, Qur’anic verses calling for war, the sayings attributed to the Prophet. These sayings offer people such as ISIS a lot of material they can work with.”

Still, Hirsi Ali believes that Islam can be reformed, that by no means are all Muslims violent or striving to implement sharia, and that the “task of reform can only be carried out by Muslims.” She reminded me that Obama said he believed this as well. “That,” she added, “is one of the great public policy riddles of our time: how could an intelligent president such as Barack Obama personally favor reforms within Islam yet be so unwilling, as a matter of policy, to do anything to support genuine Muslim reformers and instead empower Islamists such as the Brotherhood in Egypt? It’s a tremendous missed opportunity, for which we are now paying the price as Political Islam is ascendant in the world.”

But what concerns her most is how the United States responds to the Islamist threat.

Before delving into Hirsi Ali’s advice, it’s worth establishing the premises framing her argument. Islam, while possessing the supernatural characteristics of its Abrahamic predecessors, propounds an ideology of temporal control and submission. “Islam,” after all, means “submission” – by mankind, to the will of God, here on Earth. The very name of the faith manifests its essence, implying confrontation between a deity who commands and mortals who must obey – or else. Nowhere in Islam’s foundational texts does there reside a declaration equivalent to Jesus’s “Render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and unto God the things that are God’s.” Islam’s foundational texts do not preach separation between mosque and state. Everything belongs to God.

Islam’s command to submit pertains not just to Muslims, but to humanity as a whole. (“People of the Book” – i.e, Jews and Christians – are granted some leniency in this life, but the Quran, regarded by Muslims as the perfect, inalterable Word of God, leaves no doubt that hellfire awaits nonbelievers.) Make no mistake about it: a future in which an unreformed Islam prevailed would be grim indeed, inimical to every Enlightenment value and every liberal principle, and thus to our Constitutional order and the protections it affords minority rights (women’s rights, LBGT rights, and so on) of all sorts. That such a future is improbable is irrelevant; the threat comes from those willing to kill to bring it about. They – and not Hirsi Ali – are the ones obliging us to have this conversation.

Hirsi Ali is concerned with the menacing political ideology that permeates dawa. As practiced by Islamists, dawa, she says, aims both to convert non-Muslims to Islam and to “instil Islamist views in existing Muslims.” Dawa is the “subversive, indoctrinating precursor to jihad.” It, thus, constitutes a threat, but since it is “an ostensibly religious missionary activity, proponents of dawa enjoy a much greater protection by the law in free societies than Marxists or Fascists did in the past.” Government agencies have been “duped into regarding” Islamist groups “as representatives of moderate Muslims simply because they do not engage in violence.”

Hirsi Ali names the best-known Islamist organizations, and they include “mainstream” ones often cited uncritically by the press. Among these figure the Council on American-Islamic Relations, the Muslim Public Affairs Council, and the Muslim Brotherhood. Yes, the Muslim Brotherhood, which the New York Times recently called “perhaps the most influential Islamist group in the Middle East” and warned against declaring a terrorist organization. (Before rushing to its defense, the Times might have noted the Brotherhood’s alarming slogan: “Allah is our objective; the Qur’an is our law; the Prophet is our leader; jihad is our way; and death for the sake of Allah is our highest aspiration.”)

These groups claim to represent the American Muslim community, but in fact do not speak for moderate Muslim reformers (with whom the United States, she tells us, should ally itself). The groups fully avail themselves of First Amendment protections. Hirsi Ali reminds us that “radicalization” – that is, holding strongly Islamist views – is not a crime, unless violence results. But crime – terrorism – at times flows from the provocative doctrines of jihad (fighting for Islam is a duty) and martyrdom (dying in jihad guarantees entry to Paradise). Jihad and martyrdom are mainstream Islam. To those who would object that jihad can mean something other than violence, Hirsi Ali told me that, “many U.S. officials let themselves be sweet-talked by Islamists and supposed experts who claim it only refers to a spiritual striving. In fact, in Islamic tradition historically, jihad of the sword came first and was primary in importance. It was only later, after the founding of Islam, that additional meanings (such as inner striving) were attached to the term jihad.“

The real problem, Hirsi Ali notes, in her paper, is that any Islamist organizations that “aren’t Al Qaeda” end up looking moderate. Before engaging with such groups, the FBI should scrutinize their ideological background to “ensure that they are not committed to the Islamist agenda;” and the IRS should revoke their tax-exempt status if they turn out to be Islamist. (This obviously means that the relevant government agencies will have to study the Islamist agenda in order to recognize it.) Likewise, the Department of Homeland Security “should subject immigrants and refugees to ideological scrutiny.” She also wants the government to “prioritize” the entry of those “who have shown loyalty to the United States,” as well as screen chaplains employed by the government. That such suggestions will sound extreme to many only shows how far off track our public discourse about Islam has wandered. She also advocates placing mosques and Islamic centers “credibly suspected of engaging in subversive activities” under “reasonable surveillance.”

Would all this increased government attention only “play into the hands of the Islamists” and effectively spur terrorist recruitment? If you answer yes, you are in fact recognizing the violence-inducing potential of Islamic doctrine, and the readiness of at least some Muslims to act on it.

Hirsi Ali explains that “[t]he most fundamental distinction between the constitution of political Islam and the constitution of liberty is in their differing approaches to human and individual life.” The “US Constitution grants individual human beings natural, inalienable, God-given rights” which the government must protect. Sharia, however, abrogates and supplants those rights with itself; “[f]or agents of political Islam the individual life is merely an instrument,” not an end in itself. The “ultimate goal of dawa is . . . to get rid of the non-Islamic political order and replace it with the order of Islamic law.” For this reason, Hirsi Ali points out that, “governments in Muslim-majority countries . . . have applied tight supervision over dawa activities.” Clueless Westerners, in contrast, “tend to see only the humanitarian side of dawa efforts.” (Not all, though, she notes: the Dutch Intelligence Agency acknowledged as far back as 2004 the subversive nature of “radical dawa activities.”)

To those who would accuse Hirsi Ali of fearmongering, she replies that the influence of Islamist participation in public life is gradual and corrosive. I would add that we see evidence of this in, say, the dread that stopped the news media from running the Charlie Hebdo cartoons after Islamists slaughtered the magazine’s staff in 2015; in the harsh grilling CNN gave the controversial anti-jihad activist Pamela Geller for holding her “Draw Muhammad” contest later that year; in the frequency with which the free-speech-inhibiting noun “Islamophobia” bespatters the press; and in the threats levelled at former Muslims – including Sarah Haider, co-founder of Ex-Muslims of North America, and, obviously, Hirsi Ali herself. There are many other examples, but what transpires as most worrisome is the support, if only tacit or through ignorance, of far too many citizens of one of the world’s most advanced democracies for an illiberal creed and its retrograde customs. In a country founded on the rights to free speech and the pursuit of happiness all this is outrageous. Or it ought to be.

Hirsi Ali has recommendations for changes to American diplomacy – chiefly, that foreign governments cease supporting Islamist activities in the United States “as a condition of US friendship,” and that the United States “punish” transgressors with “trade sanctions or cuts in aid payments.” What this would do to alliances with, say, the Gulf States, is impossible to predict (though they are not based on friendship, but calculated, mutual self-interest); but the gist of her point should be self-evident. Allies should not strive to subvert one another, and this is just what Saudi Arabia (for example) is doing by funding Wahhabi enterprises in the United States.

Inevitably these days, any discussion of Islam leads back to Trump’s signature campaign issue: Muslim immigration to the United States. As noted above, by 2030, American Muslims will number 6.2 million. This reflects, Hirsi Ali tells us, an annual growth rate “more than double that of France” (which is suffering its second year under a state of emergency imposed after a spate of Islamist attacks). Hirsi Ali observes that more than a third of the immigrants will come from Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Iraq, where – again according to Pew polling data –overwhelming majorities hold “views that most Americans would regard as extreme” about making sharia the law of the land, stoning adulterers, and homosexuality, with more than or almost half favoring death for apostates, and much else that is horrible. Significant minorities in these three countries also happen to believe that suicide bombings are “sometimes justified.”

Hirsi Ali bluntly concludes that, “People with views such as these pose a threat to us all.” Most will not turn to terrorism, she adds, but their “attitudes imply, at the very least, an aversion to the hard-won achievements of Western feminists and campaigners for minority rights, and at worst a readiness to turn a blind eye to the use of violence and intimidation tactics against, say, apostates and dissidents.” Almost half the American Muslims surveyed believe their community leaders “had not done enough to speak out against Islamist extremists;” and more than a fifth think that there exists no small amount of “support for extremism” in their communities. Yet non-Muslims voicing fears about such matters generally suffer vilification as “Islamophobes” and racists. The problem, again, is ideological, and not just a matter of demographics and certainly not of skin color; about one in four American Muslims are converts.

Hirsi Ali presents research concluding that “governments in Muslim-majority countries are well aware of the connection between dawa and jihad and have applied tight supervision over dawa activities. Tight supervision, however, is not a solution to the problem presented by dawa; it is a way of postponing a confrontation. By contrast, Western governments are generally ignorant of Islamist ideology and strategy.”

Such ignorance spawns security blunders and danger for us all. Hirsi Ali offers a grim, irrefutable litany in this regard. Although he had openly declared his support for Hamas and Hezbollah, Abdurahman Alamoudi, in the 1990s, found himself appointed by the U.S. government to choose Muslim chaplains for the military and standing side-by-side with President Bush at a post-9/11 press conference. However, in 2003 the authorities arrested him for plotting to assassinate then Saudi Crown Prince Abdullah, and later discovered him to be “one of Al-Qaeda’s top fundraisers.”

The executive director of CAIR, Nihad Awad, decried the U.S. government’s “anti-Muslim witch hunt” for raiding the offices of Ghassan Elashi, co-founder of the Holy Land Foundation for Relief and Development. But “Elashi was later indicted and convicted of channeling funds to Hamas.” (This unsettling contretemps didn’t stop the FBI from later thanking CAIR for “keep[ing] the nation safe.”) The FBI refuses to “engage in the war of ideas” with Islamists, and therefore blew it severely when it interviewed the infamous Islamist cleric Anwar al-Awlaki four times before he absconded to Yemen to preach jihad. (A drone strike killed him in 2011.) Later that year, a coalition of Islamist groups urged national security adviser John Brennan to “purge all federal government training materials of biased materials critical of Islamic theology.” Brennan duly complied, cutting 876 pages and 392 presentations deemed “offensive” to Islamist sensibilities but that doubtless would have enlightened analysts as to the Islamist danger. One wonders if any of the terrorist attacks that followed could have been prevented had Brennan not been so attendant to Islamist concerns.

Hirsi Ali announces that “In the face of a . . . genuinely subversive threat, both the executive and legislative branches of our government have a right to consider again the correct balance that must always, with difficulty, be struck between the ideals of individual liberty and the imperatives of national security.” Just “decapitating” terrorist networks abroad “cannot be regarded as a sufficient response to the threat we face.” Islamist political dogma masquerading as religion, and dawa, its means of propagation, demands attention.

If Hirsi Ali’s critics are tempted to cite statistics minimizing the threat, they will have to explain at what point – after how many more deaths – they will consider it necessary to take action. Perpetuation of the “the illusion that a line could somehow be drawn between Islam, ‘a religion of peace,’ adhered to by a moderate majority, and ‘violent extremism,’ engaged in by a tiny minority” is not the answer. Dealing forthrightly with Islamist ideology is.

That means speaking openly and rationally about it with Muslims. Hirsi Ali told me that “By being honest, we can ask Muslims the question: what needs to be reformed, and how can Muslims go about reforming problematic tenets? If we deny that there is a need for reform in mainstream Islamic religious law (Shariah), we are only empowering the Islamists.” I would add that we should remember the stakes and overcome our fear of causing offense, and recall the ultimately salutary effect of free speech. Milton’s wise words ring out to us down through the centuries: “Let [Truth] and Falsehood grapple; who ever knew Truth put to the worse in a free and open encounter? Her confuting is the best and surest suppressing.”

There is much more of note in Hirsi Ali’s paper, which, again, I urge you to read for yourselves. Its overarching message: the United States needs, finally, to stand up for the values on which it is founded.

We ignore her words at our peril.

See also:

Islam’s Liberal Counter-Insurgency

Free Speech and Islam — In Defense of Ayaan Hirsi Ali

On Betrayal by the Left – Talking with Ex-Muslim Sarah Haider