Islam's Liberal Counter-Insurgency

In her new book ‘The Battle for British Islam,’ campaigner Sara Khan offers a work of admirable frankness, determination, and moral clarity.

A review of The Battle for British Islam: Reclaiming Muslim Identity from Extremism, by Sara Khan. Saqi Books (September 2016) 256 pages

In his 2004 book The War for Muslim Minds, the French political analyst Gilles Kepel offered a stark review of the ongoing struggle to reconcile Islam with modernity. At the time of writing, the democratic project in Iraq was collapsing into escalating disorder and sectarian terror. More ominously, America’s inability to police the mayhem, the revelations of prisoner abuse at Abu Ghraib, and the failure to uncover the promised WMD stockpiles were not only damaging American credibility, but also the credibility of Western democratic ideals themselves.

In the book’s final chapter, however, Kepel turned his gaze towards Europe and found grounds for optimism. Here, he argued, democratic participation offered Muslim reformers with unprecedented opportunities. Unencumbered by the violence, corruption, and authoritarianism strangling open discussion and progress across the Muslim-majority world, a new generation of activists might succeed in defining and fashioning a secular and progressive Islam, liberated from the retrogressive doctrines that were pulling the Middle East apart. But this attempt, he warned, would meet with resistance. “The crucial importance of the battle for Islam in Europe has not escaped the attention of those who wish to build an internal citadel on European soil, where the articles of faith are frozen in the ‘land of unbelief.’”

The Battle for British Islam is a sobering report from the trenches of this war of attrition, written by activist Sara Khan in collaboration with independent counter-extremism consultant Tony McMahon. Khan’s book is neither a memoir nor a Cri de Coeur. Instead, Khan offers a clear and measured exploration of a fraught and complex struggle, identifying its most important ideological actors and flashpoints with a controlled urgency. “The battle within Islam,” she writes in the opening pages, “encompasses much more than the challenge of terrorism. At its heart is a conflict of ideas and a question as to whether Muslims believe Islam is reconcilable with pluralism and human rights . . . These disputes among British Muslims define the battle for British Islam.”

Khan is indignant that her faith is being defined and “toxified” by Islamists, whose rhetoric and violence are drowning out voices of moderation. But she has scant patience for evasive apologetics or platitudes, pointing out that “it is not enough to say that Islam is a religion of peace when clearly some are using the theological building blocks to justify war.” More immediately, Khan is alarmed by the demonstrable harm caused by Islamists and the unforgiving ideology they espouse:

I have seen at first hand how this ideology has ripped families apart, turning daughters against mothers and sons against fathers. It has robbed kids of their childhood and their promising futures, and has even groomed teenagers to be killers. It has encouraged intolerance and the dehumanization of both non-Muslims and other Muslims, furthering sectarianism, acts of excommunication and even violence. Islamist extremism provokes anti-Muslim hatred and creates polarized communities; yet despite the damage it causes, it continues to thrive among some Muslims in the UK.

Khan begins by asking why this is. What would move a bright teenage girl to abandon a secure life in a liberal democracy for a perilous one in ISIS’s strange and punishing caliphate? Khan is unimpressed by claims that deprivation is a driver of radicalization, noting that many convicted jihadists are well-educated men and women from comfortable middle-class homes. And while she acknowledges the centrality of Western foreign policy complaints to Islamist propaganda, she objects that a “positive buy-in to an ideology is also required . . . There has to be a belief system present that legitimates and necessitates violence.”

Radicalization, Khan argues, occurs at the nexus of ideology and identity. An adherent’s initial grasp of religious and political doctrine may be weak, but this matters less than the foundational conviction that the West is fallen, hostile, and irredeemably corrupt. This is a transformative process, during which the adherent is incrementally pried away from society, then from their non-Muslim friends and colleagues, and finally from their family, before assuming a new identity and becoming, in Khan’s words, “something they had not been before . . . Crucially, they come to feel that it is impossible to belong to Britain because their religious and national identities can no longer be reconciled.”

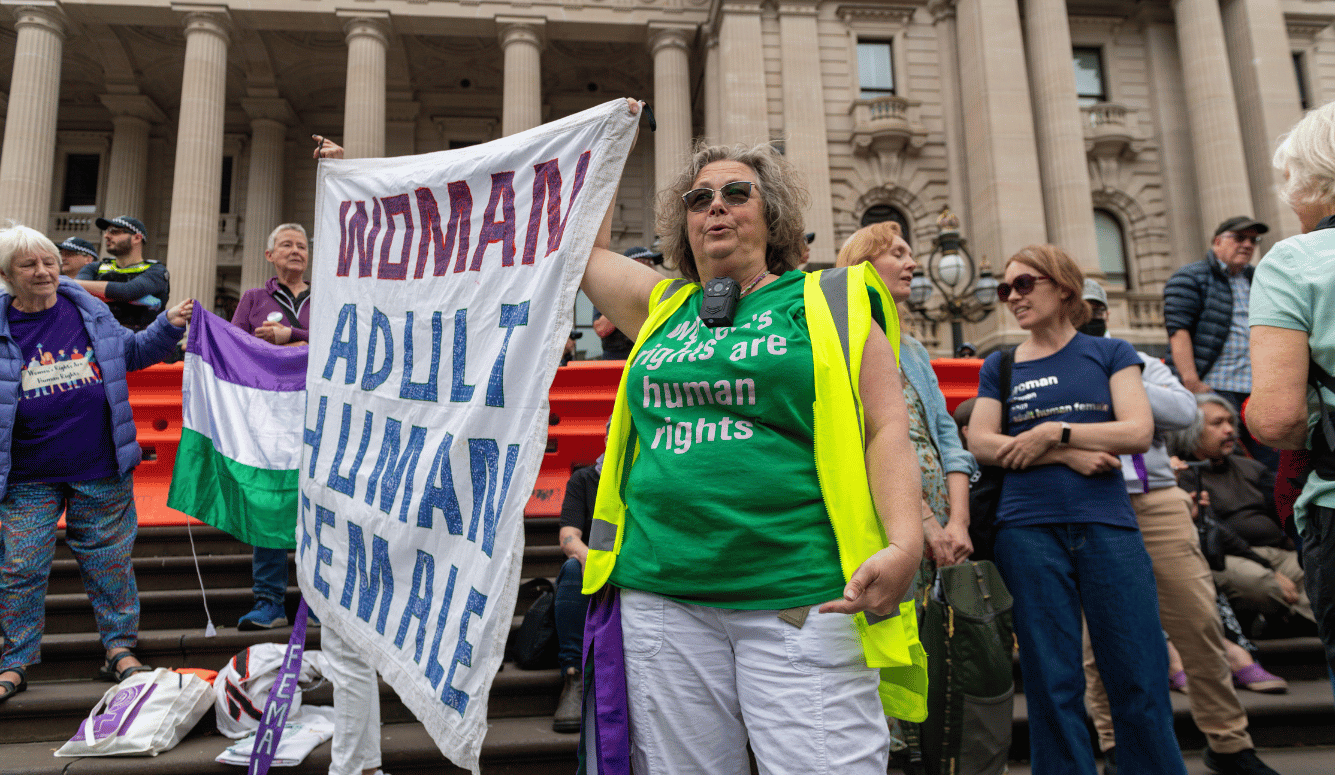

State and civil society measures designed to arrest this slide have been duly met with the expected opposition. Salafi traditionalists (advocating a return to 7th Century traditions and mores) and doctrinaire Islamists (promising a revolutionary and modern state-based totalitarianism) may have quarrelled throughout the 1990s, but neither was slow to understand the need to co-operate once the twin towers had come down. Given their easy agreement on things like the moral turpitude of the democratic West, fierce antipathy to the emancipation of women, the revulsion elicited by homosexuality, support for barbaric hudud punishments (conditions may vary) and blasphemy laws and so on, it is faintly amazing they didn’t get around to this sooner. But as Western governments brought greater scrutiny to bear on Islamic organizations, bookshops, preachers, websites, and mosques, the state of siege it produced among Islamic extremists of all stripes made co-operation inevitable.

The British government’s response was to develop a four-part counter-extremism strategy known as CONTEST in 2003. Oddly, the most controversial part of this policy turned out to be the ‘Prevent’ strand which sought to identify and protect those at risk of radicalization before they were drawn into criminality. Long before Prevent was put on a statutory footing in 2015, Salafi-Islamists were already mounting a co-ordinated and cynical campaign of disinformation designed to re-describe a policy of protection and rescue as a sinister neo-McCarthyite plot designed to harass, persecute, and spy on embattled Muslims.

The political Left, reflexively sympathetic to minorities no matter what they say or do, eagerly imbibed this scaremongering and then mindlessly regurgitated it into the pages of the Guardian and the Independent with very little resistance from a government apparently uneasy with defending its own policy. For Khan and other activists working on the ground, this has been exasperating. Khan concedes that the Prevent strategy is imperfect, but she is convinced of its necessity, protective of its reputation, and dismayed that the paranoid and conspiratorial Salafi-Islamist propaganda narrative has been allowed to trash a vital and frequently effective government initiative. Islamist activists posing as distraught parents tour TV studios peddling anguished tales of interrogation and surveillance of Muslim schoolchildren for the benefit of credulous news anchors and journalists. By the time such stories turn out to be lurid confections of exaggeration and fabrication, public interest and media sensation have moved on, leaving only sinister perceptions of state authoritarianism trailing in their wake.

For Khan and the other liberal Muslim activists she profiles in a section devoted to what she calls “voices from the frontline”, the hostility of the Salafi-Islamist front was to be expected. As, to a lesser degree, was the hostility of the nativist far-right, which is ideologically disinclined to make distinctions between this Muslim or that one based upon what an individual believes. Enemies such as these come with the territory. But when Khan discusses the perverse and spiteful behavior of the political Left, the sense of betrayal is palpable.

For the unreconstructed far-Left, the red-green socialist-Islamist alliance is a matter of cynicism and short-term expediency. The two parties have enemies in common (Israel, America, the wider West) and share an antipathy to capitalism and liberal democracy. This gruesome partnership between secular Marxists and theocratic fascists fared well during the war in Iraq when the two factions united to oppose the overthrow of Saddam Hussein. It has fared rather less well during the Assad regime’s ongoing pulverization of Sunni Muslims in Syria, where Islamist support for the Syrian rebellion has encountered the immovable object of the far-Left’s unreflective anti-Americanism. Nevertheless, shared areas of concern persist, and neither side can find a good word to say about someone like Khan who is reliably defamed as the pliable stooge of malevolent state power.

Meanwhile, on university campuses across the country, the student Left has bound itself up into an incoherent knot over ‘Islamophobia’. From young radicals neurotically mesmerized by the taxonomy of identity and the hunt for this-or-that –phobia or –ism, one might expect an unequivocal rejection of Islamist politics and Salafi reaction. These are, after all, political groups who demand the veiling and subjugation of women, the stoning of adulteresses, the execution of homosexuals and apostates, and the mass-murder of Jews (or Zionists, depending upon how careful a given speaker decides to be).

And yet, the sickly cultural relativism that has swallowed large parts of the Western Left whole has caused student radicals to wave away concerns about the Islamic far-right’s bottomless capacity for out-group hatred. Instead they have condescended to adopt Islamists as their wards, welcoming jihadist activists like Moazzam Begg onto campus to denounce the alleged injustice of Western foreign policy and counter-extremism measures, whilst stigmatizing human rights campaigners like Peter Tatchell and Iranian ex-Muslim Maryam Namazie with spurious allegations of bigotry and ‘Orientalism’. When Namazie was heckled and intimidated by Islamist activists during a presentation she gave at Goldsmith’s College in London, the university’s LGBT and Feminist societies both advertised their progressive credentials by releasing statements declaring their solidarity with her tormentors.

All of which means the political space occupied by activists and campaigners like Sara Khan is vanishingly narrow. But it is upon the shoulders of activists like her that Gilles Kepel placed the hopes of a liberal counter-insurgency back in 2004: It is “these young men and women” he wrote, “[who] will present a new face of Islam – reconciled with modernity – to the larger world.”

For the dubious pleasure of this imposing responsibility, Khan and her allies are shunned by the Left and maligned by the Islamist and nativist Right. Even so, what’s striking about her book is the absence of self-pity. Instead, Khan offers a work of admirable frankness, determination, and moral clarity. “I write this book,” she states simply in the introduction, “because I believe we can forge a better path to a future based on human rights, shared values, compassion and co-existence, prizing such aspirations over discrimination, hatred and supremacy. The question is whether we are brave enough.”