Education

Make Expertise Great Again

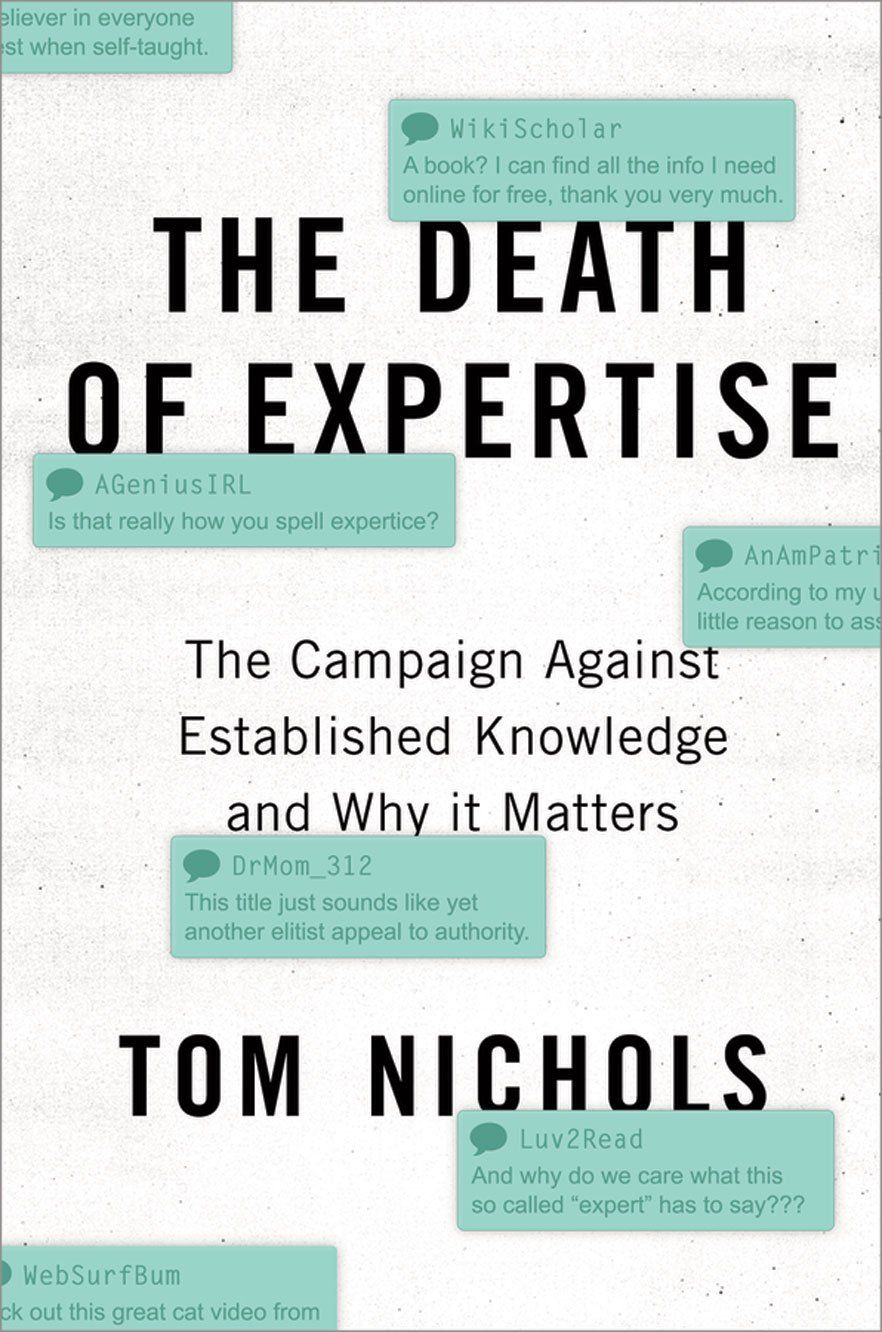

The Death of Expertise: The Campaign Against Established Knowledge and Why It Matters is finally out this year.

A review of by The Death of Expertise: The Campaign Against Established Knowledge and Why It Matters, by Tom Nichols. Oxford University Press, (1 April, 2017) 272 pages.

The long-awaited book by Professor Tom Nichols, (AKA @RadioFreeTom) The Death of Expertise: The Campaign Against Established Knowledge and Why It Matters is finally out this year. And perhaps no other topic can be as important, given the tectonic shifting year in global politics we just had. Political Scientists don’t often get credit for genuine predictions or trend recognition, although the majority of them invite flak for failed ones. Credit, therefore goes to Nichols. He identified, what is currently one of the most destructive trends in this post-truth world, a disdain towards any sort of acquired knowledge and expertise, and he identified that trend in 2013 in this famous blog post.

That blog post was expanded to a full length Op-Ed for The Federalist in 2014, which came out as a complete thesis in the first month of 2017. The book, which is soon to be available, in both hardcover and Kindle, is reasonably priced and is written in casual non-academic way, so it is an easy read for both academics, policy makers, as well as “non-experts,” so to speak.

I have been following the work of the good Professor since 2014, and there was a time, when he was the only academic I followed on Twitter. This was not just because of his actual expertise in grand strategy, Russia and nuclear weapons (which is related to my research) but because in this day and age of postmodernism and moral relativism, Nichols genuinely tries to be objective and neutral on any given political issue. This blind devotion to factual inquiry, is refreshingly Old School and non-tribalistic. So it is in that spirit of objectivity, that I couch my understanding and critique of Nichols’ central thesis.

Virulent strains of anti-intellectualism and class envy are not something new in the broader Anglosphere, especially in America, as well as in Britain. Historically it has ebbed and flowed, and leaders from both sides of the political spectrum have cynically paid lip-service to anti-intellectual and anti-science populism for short term gains.

However, given the unique representative liberal democratic system, both Parliamentary and Presidential, the anti-intellectualism in the West has never wreaked havoc like Nazi Book Burning, Soviet Lysenkoism, or the Chinese Cultural Revolution. It is generally accepted that not everyone is capable of having informed opinions about everything under the sun, and so naturally expertise is segmented. That is not to say that intellectuals are demi-Gods. As Thomas Sowell wrote in Intellectuals and Society, there needs to be a conservative and healthy skepticism and wariness of intellectuals, but one also needs to be careful that it doesn’t cross to an unreasonable hatred for anyone with greater knowledge. Nichols here channels his conservative namesake, when he tries to finds the causality of the current political turmoil and mood across the West, and tries to answer the question of why facts are being rejected on both sides of the Atlantic.

Nichols points out three fundamental flaws, none of them new, but each increasingly intertwined and pushing us towards societal collapse. First he addresses the current lack of civility in discussion and discourse across the West, and the broken social contract. Conversation, or debate, are not mere argumentative disputes anymore, they frequently border on open hostilities. People increasingly seem unable to debate without condemning their opponents as idiots, marking them as beneath respect for their views.

Secondly, Nichols lays the blame of much of our societal destabilisation at the feet of social media.

Social media, and the proliferation of information has given rise to two things. On one hand, it has given rise to superficiality. (An example would be that anyone can google the American Constitution or the Bill of Rights, however, that doesn’t make them a Constitutional law expert, which requires studying thousands of different case studies, the political symbolism behind each decision, the dissenting opinions, the moral and legal dilemmas, precedents, and so on.) Similarly in other fields, like vaccines, GMOs, macroeconomics, or national security, each require their own unique deep knowledge and years of dedicated study.

While social media driven superficiality is increasing, our education systems are becoming more degraded at the same time. In both the US and UK, universities have wound back the focus on factual knowledge, scientific inquiry, civics, history and ancient philosophy, and have started focusing on feelings, sociology, gender studies, post-colonial studies and other postmodern gibberish. This has naturally left a knowledge vacuum which has inevitably been filled by the superficial sound bytes gleaned from Facebook and Google.

Similarly, the comment culture of clickbait blogging, celebrity activism, talk radio and internet punditry, coupled with zero theoretical knowledge has also added fuel to the fire. For example, in an earlier age, it was the educated who read newspapers, and then went on to write letters to the editors. Today, however, Lily Allen can cry on TV for 30 year old “child” migrants, and Ben Affleck can shout down Sam Harris on live TV. Anonymous rubes who mostly don’t read articles apart from their headlines, but comment nonetheless, continue to cement their own cocooned echo chambers.

This is having enormous effects. Rationality and wisdom are being discarded, and a quasi-Marxist forced equality — where frankly everyone thinks they are equal to everyone else in everything — regardless of their competence or quality, is resulting in a hyper-chaotic Dunning-Kruger world. It is not elitism or an appeal to authority to point that out, that democracy doesn’t mean everyone is qualitatively equal to everyone else in experience or knowledge. What it means is that everyone has equal protection under the law and is guaranteed some basic freedoms and rights. These are two fundamentally different concepts, but they are being blurred thanks to social media and the widespread lack of genuine education.

And it is in education where Nichols fires his third bullet, and where I find myself strongly agreeing with him. Nichols points out what has become all too clear over the past half decade, that the academics have left the education industry in the hands of students, bureaucratic managers, and a handful of radicals desperate to re-engineer society and human nature.

Modern universities, according to Nichols, have more or less ceased to be institutions of higher learning, and are nothing more than commercial enterprises, making up random, meaningless degrees with zero real world values, and urging naïve students to spend millions to “chase their dreams” regardless of the laws of demand and supply and future job prospects. As someone who recently started teaching at his second Uni, I wholeheartedly agree. Nothing in this planet is as annoying as self-satisfied undergrads with half-baked knowledge and zero wisdom.

It is important to note, at this stage, that none of these three flaws are self sufficient or uniquely responsible for the societal car crash we are observing across the West. They are all happening at the same time in some miserable coincidence, like a perfect storm. Four hundred years ago, the structural forces of the Industrial Revolution, scientific inquiry and proliferation of Renaissance values helped the world leap from feudalism to modernity. Ironically, this time, the movement is in reverse.

Nichols’ book’s not without flaws. While the assessment is there and the evils identified, no alternative or policy prescription is suggested. So, what should be done? Should there be academic societies and mandatory programs (such as history, logic or statistics) in every university course? Should we start aggressively promoting a new realism in the arts, science, and every other academic discipline, where only evidence and nothing but evidence will be needed for anyone to be taken seriously?

And what sort of checks and balances should be instituted on social media? Society is ever mutating, and with the advent of new technology. So how will harness and categorise all of our new access to information? Who will be the new gatekeepers? Unfortunately Nichols does not attempt to address these questions.

Secondly, being from academia myself, I feel that Nichols let academics off the hook a little too easily. And perhaps, this is the core issue, which needed to be touched on more.

It is less of death of expertise, but rather a dilution of expertise that has led to our current crisis point. And academics more than anyone else are responsible for that. It was academics who created Women’s Studies departments virtually overnight in the 1970s, without any consideration given to the scholarly foundations of such departments. It was academics who have promoted anti-scientific and anti-Enlightenment disciplines within the academy, under the euphemistic umbrella of “Critical Theory.” And it was academics who created self-referential journals, Impact Factor madness, and other research areas with zero policy relevance and real life utility. If our fellow academics receive thousands of dollars of taxpayer’s money to study “Real Vampires“, or “Whiteness of Pumpkin Spice Lattes” we are hardly absolved of blame, are we?

That said, this book is more than topical and is exceedingly important. Every global period of turmoil forces humans to self-reflect, and today’s era is no different. The early nineties also saw paradigm wars, from Francis Fukuyama, John Mearsheimer to Samuel Huntington; from The Bell Curve to the Sokal Affair. And last year we saw Mark Lilla’s terrific essay, as well as Jason Brennan and Paul Bloom’s phenomenal intellectual contributions.

It seems that Professor Tom Nichols has successfully carried the torch to start this year.