History

The Masochists Who Defend Sadists: The Regressive Left in Theory and Practice

John Pilger, Michael Moore, Tariq Ali, Arundhati Roy, and the Stop the War Coalition have shown their commitment to barbarism.

I.

The most contemptible of John Pilger’s declarations of left-wing solidarity was made in an interview with Green Left Weekly in January, 2004. The Australian journalist was asked whether the Left should support the anti-occupation movement in Iraq. Pilger replied:

Yes . . We cannot afford to be choosy. While we abhor and condemn the continuing loss of innocent life in Iraq, we have no choice now but to support the resistance.

One must remember that in the ranks of the resistance were the Ba’ath party loyalists and the newly arrived jihadists of al Qaeda, who set out to foment sectarian war and leave Iraqi civil society in ruins. And they succeeded. For Pilger, the fascists and Islamists were the true friends of the Western Left.

Pilger had a lot of other friends, too. Radicals and populists such as Michael Moore, Tariq Ali, Arundhati Roy, and the Stop the War Coalition came out to support the resistance, oppose the United States, and demonstrate their commitment to barbarism.

There were many decent and moral ways to object to regime change in Iraq. Bernard Kouchner’s manifesto, Neither War Nor Saddam, still seems the best, although it was and is mostly ignored or forgotten. It was an argument for complexity and patience and discernment, but these things are difficult, and indignation and self-righteousness are easy.

It cannot be understated, though: the United States and its allies had just overthrown a sadistic and totalitarian regime, and the Iraqis and Kurds desperately needed help. And yet, leftists were called upon to support the maintenance of sadism and totalitarianism. Why did the Left do this?

They hated Bush, of course, and there were good reasons for that. They feared American ambitions in the Middle East, and there were good reasons to be fearful. I think they hated the idea of the West and of Empire, so they made a practical and intellectual alliance with people who shared their hatred. It must be remembered, too, that the resistance and its fighters and ideas served as the forerunner of the Islamic State. The Western Left’s solidarity with Islamism and fascism is, I would argue, the Western Left’s greatest shame, at least in my lifetime.

None of this is to excuse or defend a disastrous and mendacious US policy. I would have opposed the war, too, but I think I can look back and judge who my enemies are.

At the time, Pilger’s declaration was met with some mild outrage and criticism, but he didn’t concede anything. He gave another interview to Tony Jones on ABC Lateline, where he argued that Australian and Coalition troops and their Iraqi collaborators were legitimate targets for murder. Of course, Pilger said he disapproved of the murder of innocents, but then again, the resistance was crucial and the whole world depended upon it, so his answers were a bit confusing. Murder was condemnable, yes, but necessary. Left was Right. Fascism was noble resistance. A few viewers must have scratched their heads and wondered what was going on. The Iraq war unhinged a lot of people, the proponents and the objectors. Maybe Pilger was always a little unhinged. I don’t think anyone should have been surprised. Pilger’s support for the resistance was entirely in line with his thinking and view of the world. That world had changed a great deal in the last few decades, but all that change seemed to have passed him by.

II.

In the 1990s, it was swiftly recognised that History, after all, had not ended: Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait; Somalia collapsed; Yugoslavia tore itself apart. The Serbian chauvinists’ gruesome addition to language, ethnic cleaning, forced the West to contemplate allowing genocide to take place again in Europe.

This was a challenging and confusing moment for foreign policy makers. There was much shuffling of feet, but eventually the West intervened and rescued the Bosnian Muslims, and then the Albanians in Kosovo, and Slobodan Milosevic and his cronies ended up in the dock.

Self-congratulation got underway, and some of that confusion lifted: Western intervention, often rightfully derided and feared, could be put to practical and humanitarian use, even when there was no self-interest for the intervening powers.

This case was strengthened not by a sterling record of success, but the greater record of failure. The shame of Srebrenica lingered, and the Western powers would have to remember that, yes, they had done the right thing, but they had done it too late. For the genocide in Rwanda, we still have to reach for a word like ‘tragedy’, even though its employment seems cheap and inadequate when we set it against what took place. Or perhaps it’s better to say what was allowed to take place, for the other moral crime had been non-intervention by the Western powers.

In these arguments, the neoconservatives and the liberal hawks united, and a consensus emerged on the necessity and morality of Western intervention, even if its legality remained a little murky.

At the same time, a contrarian argument emerged from a corner of the radical left, an argument that took issue with the consensus view of intervention in the 1990s. From here, the view was different: the standard Western narrative was a dangerous lie, and a few revered intellectuals and journalists were the holders of the truth. A vigorous debate ensued, and John Pilger’s name continued to crop up. At the height of these debates, he warned that humanitarian intervention would lead to “totalitarian world government”, and that Kosovo was nobody’s concern, not even the Serbs’. A strange argument; but no stranger than a few of the others.

In 2003, the writer Diana Johnstone published Fools’ Crusade: Yugoslavia, NATO, and Western Delusions, which, depending on your reading, was a brilliant and timely work of historical revisionism, or a second rate work of fiction.

In Johnstone’s view, the media had miscast the roles of those in the Balkan wars: the perceived victims, the Bosnians, were the true aggressors; the perceived aggressors, the Serbs, were legitimate and reasonable actors. Historian and genocide scholar, Marko Attila Hoare, summarised:

[S]he blames everything that happened there on the Muslims; claims they provoked the Serb offensive in the first place; then deliberately engineered their own killing; and then exaggerated their own death-toll. She denies that thousands of Muslims were massacred; suggesting there is no evidence for a number higher than 199 – less than 2.5% of the accepted figure of eight thousand.

Johnstone’s Swedish publisher, wary of associating itself with genocide denial, backed out. And suddenly, left-wing luminaries converged to denounce the decision and to demand that the book see publication. John Pilger, Noam Chomsky, Tariq Ali, and others signed a letter stating that Johnstone’s book was not, after all, fiction, but “an outstanding work, dissenting from the mainstream view but doing so by an appeal to fact and reason, in a great tradition.”

More scratching of heads. What was going on? Why was genocide denial, a trait of the lunatic Right, being pushed by the radical Left? And it was about to get worse.

In 2010, Edward S. Herman and David Peterson published The Politics of Genocide, another attempt at historical honesty that strayed into fiction. The authors doubled down on the myth of a massacre at Srebrenica, but this time they went further. The authors claimed that the Rwandan genocide was also a lie, or perhaps everyone had it wrong, and the Tutsis had really murdered the Hutus, or no one really knew and the truth was impossible to find. Such were the arguments. Not very good ones, I think. John Pilger, though, was quite impressed as his name appeared on the book’s cover alongside a warm endorsement: “In this brilliant exposé of great power’s lethal industry of lies, Edward Herman and David Peterson defend the right of us all to a truthful historical memory.”

At first glance, the position taken by Pilger and these left-wingers appears quite unusual. The brave writer, George Monbiot, certainly scratched his head and wondered about the claims of his comrades. He noted that if they were correct, we would have to pause to consider the very long list of those who must be incorrect: the journalists who covered the wars, the survivors who gave their testimony, the forensic investigators who uncovered the mass graves, the fact-finders of the UN and the international courts, and the perpetrators who confessed. Perhaps they were mistaken, or they were liars, or they were stooges of Western imperialism.

At second glance, it doesn’t appear unusual or surprising at all; it is exactly what one would expect. If genocides and massacres were taking place, then Western intervention would be morally and legally justified. But, for the radical left, intervention is always callous and criminal and unjustified. The Western media, forever represented by Evelyn Waugh’s Lord Copper, stirs up “a very promising little war” and the audience is deceived. And so, the enemies of the West are not enemies, but friends, and genocide is a lie, and Milosevic isn’t that bad, after all. John Pilger is rather fond of quoting George Orwell, but I think he should give it up. Pilger has a power of inventing unpleasant facts, not facing them.

And so, a careful observer watching this era of Western intervention should not have been surprised by the positions of John Pilger and the radical Left. It turns out that the defenders and excusers of fascism in the Balkans are the same people who defend and excuse fascism in Iraq.

III.

A reader or two might be thinking: why is the author wandering around a left-wing graveyard and disinterring John Pilger? Surely he doesn’t carry much influence anymore. Why breathe life into these old and decaying arguments?

I do so for two reasons. First, recent political events have given a freshness to these kinds of arguments. The former chairman of Stop the War is Jeremy Corbyn, the current leader of the UK Labour party and self-declared chum of Hamas and Hezbollah. His Shadow Chancellor of the Exchequer, John McDonnell, has a soft spot for Mao. Their Executive Director for Communications and Strategy, Seumas Milne, remains unconvinced of the demerits of Stalinism. All are unrepentantly anti-Western and anti-imperialist.If the ideas of John Pilger could be channelled into a political party, it would look like Labour under Jeremy Corbyn. Corbyn’s rise has energised and frightened the Left, probably in equal parts. So, I don’t think these arguments have gone away. I think they remain very important.

Second, John Pilger and his role in the recent history of left-wing disputation meet up with an intellectual trend that characterises the present moment. I am speaking of the regressive left, a term coined by Maajid Nawaz. The regressive left refers to the nominally liberal writers and intellectuals who have stopped defending liberal principles, and now expend considerable energy excusing and defending the Islamist movement and its vicious assault on secular and Muslim societies. The term has been stuck to writers like Glenn Greenwald, CJ Werleman, Chris Hedges, and a cluster of outlets like Salon, The Intercept, Alternet and countless others in the US and Britain.

What defines the regressive left? It is the same assumption of Western culpability and confusion between friends and enemies that led to left-wing support for genocide denial in the 1990s and for the resistance in Iraq. In his excellent collaboration with Sam Harris, Islam and the Future of Tolerance, Nawaz shows that the regressive left “leap(s) whenever any (not merely their own) liberal democratic government commits a policy error, while generally ignoring almost every fascist, theocratic or Muslim-led dictatorial regime and group in the world.”

In doing so, the regressive left has abandoned the people in the Muslim world it is supposed to be defending: the Muslim liberals, the Muslim feminists, the Muslim homosexuals, the ex-Muslims and atheists, the secular bloggers in Bangladesh, and the raped and tortured Yazidis, to name just a few.

Nawaz’s term also has an intellectual debt to writers like Nick Cohen, Bernard-Henri Levy, and post 9/11 Christopher Hitchens. A lively explication comes from the French philosopher Pascal Bruckner and his 2006 study of Western masochism, The Tyranny of Guilt. What we are nowcalling the regressive left is actually a natural condition of our philosophical make-up. Bruckner wrote: “nothing is more Western than hatred of the West, that passion for cursing and lacerating ourselves.”

The problem, however, and it is an intellectually crippling problem, is that this kind of masochistic thinking lends itself to nothingness in practical terms. Bruckner continues:

Thus we Euro-Americans are supposed to have only one obligation: endlessly atoning for what we have inflicted on other parts of humanity. How can we fail to see that this leads us to live offself-denunciation while taking a strange pride in being the worst? Self-denigration is all too clearly a form of indirect self-glorification.

The regressive left is a new term that encompasses a much older way of thinking about the world, our place in it, and what to do about it. It is a brilliant and evocative term: it brings to mind a Stalinist-left that has survived the twentieth century; it cleverly subverts the progressive label that such writers usually wear; perhaps most importantly, it is a term that will always be pejorative. When the socialist intellectual Michael Harrington called some of his ex-comrades neoconservatives, it was an insult that its targets transformed into a badge of honour. There is no risk of that here. It’s unlikely that the Art of Mentoring publishing house will commission Glenn Greenwald to write Letters to a Young Regressive. And that’s a good thing. The regressive left will discredit itself.

We can use this, among other arguments, to our advantage. When I say ‘we’, I refer to those who have noticed the regressive left and its intellectual and journalistic influence, and have worried about it. I’ll come to those other arguments, but first I want to return to John Pilger and introduce the Australian Left, which is regressive by default.

IV.

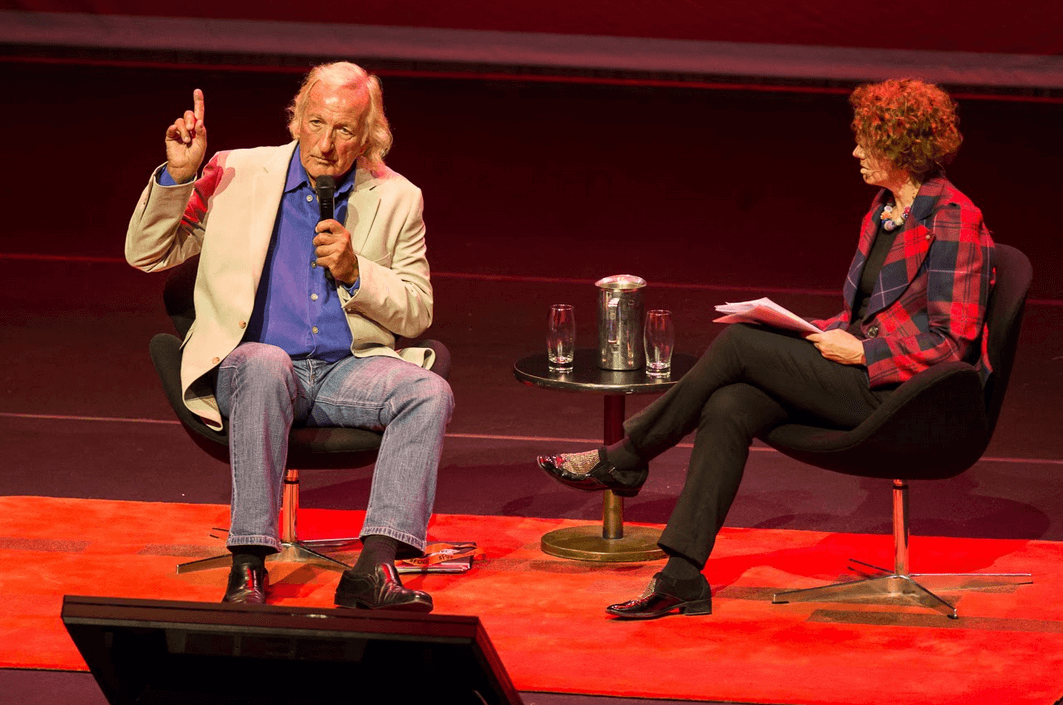

In 2014, John Pilger was invited to the annual Festival of Dangerous Ideas in Sydney, a conference of free thought and debate. His discussion was titled Breaking Australia’s Silence, and he spoke about our ‘secret’ history, our colonial sins, and our collusion with Western imperialism and its depredations. Standard fare, really. The moderator invited questions from the audience. Here is the text of the first question and answer:

Audience member: Do you think that the West should ever get involved in wars overseas . . ?

Because it feels despite our misadventures in the 2003 Iraq war and despite the problems that we’ve caused . . it feels like you’re saying . . we should just let ISIS kill whoever they want to kill and commit genocide however they wish to . . . don’t we still have a moral responsibility to help the people who have been beheaded, killed and crucified on the streets of Syria and Iraq right now?

Pilger: It’s interesting about this hideous beheading, isn’t it? . . . How much do you know about the beheading of Aboriginal people in the early days of this country?

Can the reader imagine the reaction? Of course you can. The audience broke into rapturous applause. Pilger retorted that the Iraq war cost hundreds of thousands of lives, and he was right. He didn’t mention, though, that the primary cause of those deaths was the united forces of Ba’athism and jihadism, the thugs and fanatics and friends of John Pilger and the Western Left. The questioner was berated for being “very selective”, but the irony, like everything else, was at Pilger’s expense.

I wonder, though: why was the audience clapping so enthusiastically? What were they thinking? Were they thinking at all? Maybe they appreciated the attention redirected to Aboriginal affairs. Maybe they worshipped John Pilger and would have applauded no matter what he said. Still, I wonder.

The mistreatment of Aboriginals is a source of national shame, and this is seldom unacknowledged. But Pilger’s invocation of Aboriginal suffering was deliberate distraction, a rhetorical red herring.

I think this interaction between Pilger and the audience is a perfect example of the regressive left’s cast of mind: A tragedy is at work in the present, but we will ransack the past to find an inexpiable sin; we can hold that sin against us, and in doing so, we rid ourselves of moral authority and moral responsibility; remind us of our colonial guilt, and we offer applause, but what we’re really doing is offering ourselves up for flagellation.

The regressive left is sinister and ahistorical; it is led by masochists who defend sadists; it is an attempt to make the world safe for fascism. It must be resisted and discredited.

V.

John Pilger’s ideas, meagre though they are, as well as his style of arguing and posturing, have had an outsized influence on the Australian Left. This is most apparent at the independent news site, New Matilda. The editor and owner, Chris Graham, collaborated on Pilger’s documentary, Utopia, and he also republishes all of Pilger’s essays, usually with a laudatory introduction.

It’s hardly surprising, then, that almost everything else that New Matilda publishes seems to have been written by aspiring Pilgers. There is a pervasive sense of outrage accompanied by guilt: a synthesis that avoids the problem at hand by diminishing the West’s moral authority and its responsibility to act.

Take, for example, the Islamic State’s burning of a Jordanian pilot in February, 2015. At the very least, one might expect condemnation. Not New Matilda, which published an article by Chauncey Devega titled: Yes, ISIS Burned A Man Alive: White America Did The Same To Black People By The Thousands. Does this remind you of anyone?

Here, in a title and a nutshell, is New Matilda’s foreign and editorial policy.

In January, 2015, jihadists murdered Charlie Hebdo cartoonists for the crime of being cartoonists, and they demanded that laws concerning Islamic blasphemy be imposed upon Western societies by fear and Kalashnikovs. Solidarity, that most important word in left-wing vocabulary, was lost on New Matilda, who was decidedly not Charlie. If anything, Charlie was a bit of an arsehole. Instead, New Matilda expended considerable energy lamenting offensiveness and hypocrisy and worrying about everything except the Islamist assault on free speech.

Some time later, Graham, taking his cue from John Pilger’s unwavering humourlessness, mocked those who had given their support to Charlie Hebdo in the first place. The new cartoons in question featured a drowned Aylan Kurdi under a McDonalds sign. There was something here about the Christian Right and its vacuous thinking about Muslims, and even a barb about Western capitalism. Graham, however, took an entirely literal approach, which lent itself to misunderstanding and wounded feelings. Satire, clearly, is too much for Graham; he can’t even manage Google Translate.

In the aftermath of the November Paris attacks, when the death count was still fluctuating, Graham tried to highlight the hypocrisy of Western attitudes to terror: “As France enters yet another period of mourning. Lebanon is just emerging from one. Not that you probably heard anything about it.”

Did he not realise this was an insult to his readership? Did he simply assume that everyone was entirely lacking in liberal internationalism, solidarity, and the capability of reading a newspaper and being affected by two tragic stories at the same time? He concluded, and perhaps you can detect the undertone of glee: “Westerners are finally being given just a small taste of the constant fear that people from other nations have endured for generations.”

This is pure and unadulterated Pilger, who wrote of the 9/11 jihadists and the oppressed peoples they apparently represented: “Their distant voices of rage are now heard; the daily horrors in faraway brutalised places have at last come home.” New Matilda and John Pilger are one and the same.

In this selection of New Matilda’s output, I don’t think I have misrepresented the site’s overall political stance and style of argumentation. Shall I try to be fair? I must say, it’s difficult. The other columnists and contributors strike me as the kind of people who, during their first year of university, read Noam Chomsky, exclaimed some variation of ‘Golly! This is swell!’ and the decided never to read much of anything else.

All right, then. I often admire New Matilda’s coverage of Aboriginal affairs, as well as its commitment to environmental issues. Perhaps New Matilda can be saved. I worry, though: the intellectual ground on which it rests has been long manured by Crikey, Overland and Guardian Australia. New Matilda must walk away from the regressive left and its fidelity to John Pilger.

Pilger, it must be said, is irredeemable. In 2003, he wrote that the the US administration was “the Third Reich of our times.” Over a decade later, he looked across the world and saw the rise of the Islamic State, the recrudescence of Russian nationalism, the disintegration of democratic aspirations in the Middle East, and he warned darkly that we faced the threat of fascism . . in the United States. Clearly, Pilger has relinquished any remaining sense of historical and intellectual seriousness. Even on issues where I would find agreement, that agreement is immediately undercut by Pilger’s eschewal of complexity, the insistent nastiness, the cheeriness that lurks behind invocations of tragedy and Western wrongdoing. No, I can’t find any merit in all the documentaries and essays and polemics. Pilger’s life’s work is a primer in how not to be a journalist.

VI.

In 2003, the American intellectual Paul Berman published Terror and Liberalism, which is still the most indispensable contribution to the post-9/11 literature. Berman looked at the War on Terror as a confrontation with totalitarianism, the same confrontation that had left much of the twentieth century in ruins and mass graves.

Berman asked: how were the totalitarian movements like Stalinism and Communism fought against and discredited? This was the war of ideas, a war that drew on the literature of Camus, Arendt, and Koestler, a war whose battle fronts were the small magazines of intellectual life. Berman updated that struggle for the present moment:

The Terror War was fated to be fought on that same plane – the plane of theories, arguments, books, magazines, conferences, and lectures . . It was going to be, in the end, a war of persuasion – a war that was going to be decided in large part by writers and thinkers whose ideas were going to take root, or fail to take root, among the general public.

Today, this war is more necessary than ever. It is a war for democracy and liberalism and human rights and pluralism and secularism, because these things will always need defending. A decent and anti-totalitarian left is mobilising; it must take on the Islamists and their Western apologists at the same time. Everywhere I look there is a reckoning with the regressive left: in essays and books, in podcasts and Youtube presentations, on blogs and social media.

What will success look like? I’m not entirely sure. In the meantime, though, it will be helpful if more people begin to wonder: how is it possible that for so long a reactionary crank like John Pilger could be mistaken for a man of the Left?