Blog

Reading Hannah Arendt with Roger Berkowitz: Quillette Cetera Episode 39

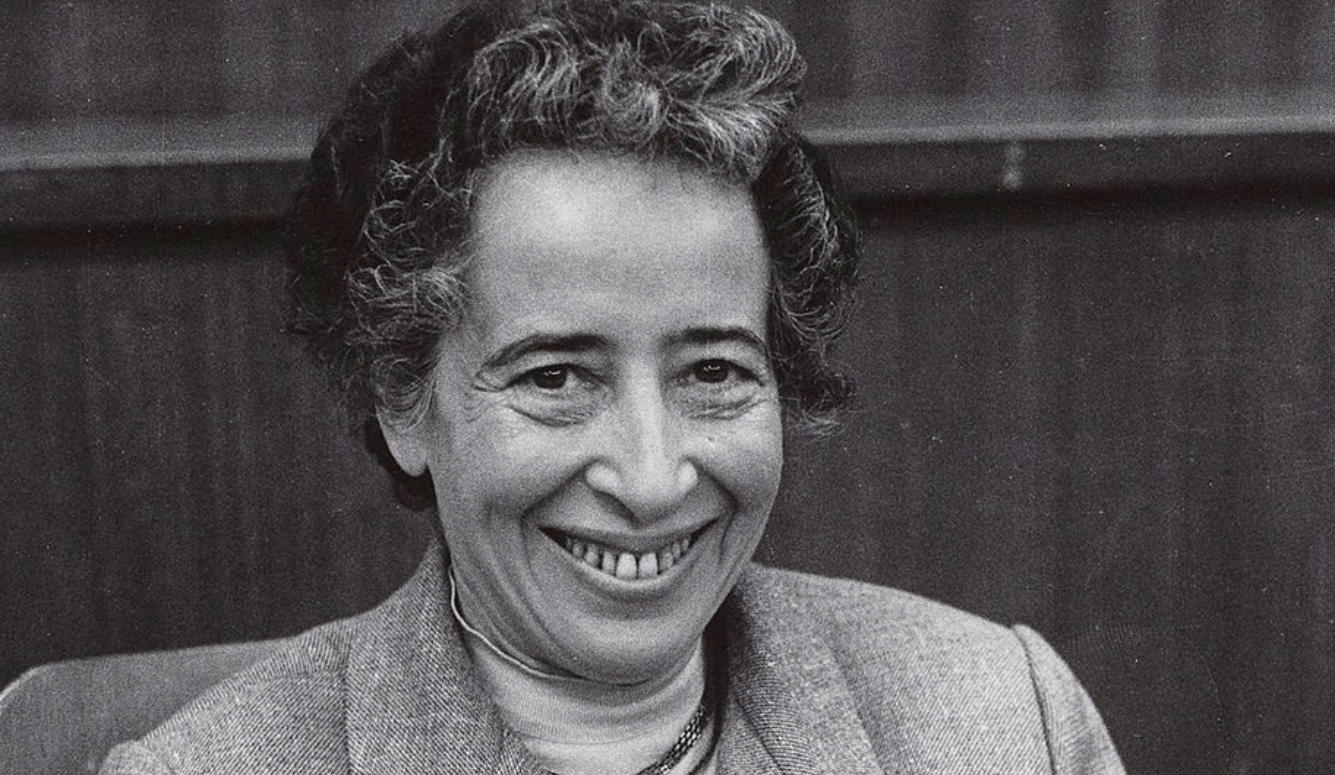

A conversation with Roger Berkowitz, the Founder and Academic Director of the Hannah Arendt Center for Politics.

In this conversation, Roger Berkowitz unpacks the lasting relevance of Hannah Arendt’s thought, emphasising her practical approach to politics. Arendt, known for her scepticism of intellectuals and bureaucracy, was less interested in abstract philosophy and more focused on how we navigate power and truth in the real world. Berkowitz also explores Arendt’s complex stance on Zionism and antisemitism—supporting a Jewish homeland while critiquing ethnonationalism.

At the heart of Arendt’s philosophy is the idea that politics is not about consensus but about the ability to disagree respectfully. In today’s polarised climate, Berkowitz argues, Arendt’s insights offer crucial guidance on engaging with difficult political realities.

Zoe: Roger, thank you so much for joining me today. To start with, I want to talk about why Hannah Arendt? What got you interested in her in the first place?

Roger Berkowitz: Well, it came in stages. I read her as an undergraduate. I remember one of the first classes I ever had at Amherst College, George Kateb, a brilliant political theorist, gave a lecture on Hannah Arendt and The Human Condition. I wrote a paper on her as a freshman in college. That’s not the answer to your question. I went on to grad school. I got a PhD in jurisprudence of all things.

I read a little Hannah Arendt in grad school. My first year, I took a course with Hanna Pitkin and read Arendt. But then the rest of my graduate school career, I was reading other things and doing my dissertation, which became a book called The Gift of Science. She doesn’t make an appearance. After a few years of teaching, I got hired to teach at Bard College, a liberal arts college in New York State.

She’s buried there, and her library is there. So, a couple of reasons. Her second husband, Heinrich Buescher, was a professor there for 17 years. They had a summer house nearby, and she had a connection to Bard through him. But also, she had become friendly with a brilliant student of hers named Leon Botstein at the University of Chicago when she was teaching there. When he became president of Bard, she vouched for him.

When her husband died, he was buried at Bard. She had a bench erected in front of his grave, and she’d come up, sit there, and read. When she died, she asked to be buried next to him. She left her library to Bard.

When I was hired, I wasn’t an Arendt scholar. It was 2005, and in 2006 was the 100th anniversary of her birth. I went to the president and said, “Let’s have a conference on Arendt.” He said, “How do you want to do it?” I said, “I don't know, but I think she's fascinating. Why don’t we invite 20 smart people and have them talk about why Arendt matters?” We did, and it was this amazing conference called Thinking in Dark Times. Afterward, her literary executor, Jerry Cohen, came up to me and said, “Start the Arendt Center.” I said, “I’m not an Arendt scholar.” He said, “I don’t care.”

Zoe: So she was about practical philosophy, right? Is that why she would have loved your conference? Because it was less about presenting papers and more about engaging with ideas?

Roger Berkowitz: Yeah. She knew the history of philosophy, the canon of German poetry by heart, and wrote in three languages. But what really marks who she is—and I think what you mean by practical—is she wrote about the world. She wasn’t interested in philosophy for philosophy’s sake. When she was interviewed on German TV in 1963, she said, “I’m not a philosopher.” She didn’t want to be called that.

She was going to write about antisemitism, totalitarianism, education, freedom, or authority using poetry, philosophy, and history in a way that was unique. People criticise her—“she’s not a real philosopher, not a real historian”—but she brings wide erudition to bear on particular issues. People ask me, “How do you choose who to read in the newspaper or magazines today?” I look for people whose work surprises me. I don’t want someone who tells me the liberal or conservative view; I want someone like Arendt, who tried to think through a problem in her own way.

Zoe: She believed there was no political truth, but what about moral truths? Did she believe in objective truth?

Roger Berkowitz: She wouldn’t call herself a post-structuralist but a post-metaphysical thinker. She doesn’t believe in metaphysical truths. There are logical and mathematical truths, but she doesn’t believe in objective moral or political truths. But that doesn’t mean there aren’t moral and political truths. For her, they emerge through conversation in a shared world. We build a shared ground and sky above us, which she calls truth. We need common ground to live, and a lot of her work addresses the increasing precarity of the common world.

Zoe: So relevant to today.

Roger Berkowitz: Yes, she thought the scientific revolution contributed to this. Science casts doubt on shared sense experience, moving us into a world of theories rather than observations. Science alienates us from the world. Unlike Marx’s view of alienation through labour, Arendt saw alienation through the distrust of our senses. She was suspicious of intellectuals because they build theories disconnected from reality. She famously distrusted intellectuals more than any other class and preferred talking to dock workers or ordinary people.

Zoe: Did she really think the entry of intellectuals into politics was dangerous?

Roger Berkowitz: Yes, she thought intellectuals could take us away from the common world into these theories that create a consistent fictional world, which is what she calls totalitarianism. Her thought is so original and relevant, even though she was writing about a different time.

Zoe: It’s hard to label her. But when you explain this, words like “anti-science” and “populist” come to mind.

Roger Berkowitz: She was not anti-science or a populist. Science is essential in its domain, but scientists shouldn’t tell us what to do politically. Science can give us facts, like the Earth warming, but deciding what to do about it is politics, not science. Scientists enter politics as citizens, not experts, and shouldn’t dictate policy based on their expertise.

Zoe: So, stay in your lane?

Roger Berkowitz: Exactly. Scientists provide facts, but political decisions are not science—they’re subject to debate. There are no right answers in politics.

Zoe: Trump talks a lot about intellectuals overrunning institutions. But isn’t he talking about social sciences, not hard sciences?

Roger Berkowitz: Trump doesn’t like bureaucrats or intellectuals, including hard scientists like those in the EPA. Arendt would agree that bureaucrats have too much power. She called bureaucracy the rule of nobody, where no one takes responsibility, leading to a disempowered people. This critique is often seen as conservative, but it also has a left tradition, like Thomas Jefferson’s focus on self-government. Arendt was a Jeffersonian in that regard.

Zoe: I want to dive deeper into Zionism. She criticised it, but she wasn’t an anti-Zionist, right?

Roger Berkowitz: She wasn’t an anti-Zionist. In her early life, she worked for Zionist organisations and believed Jews needed a homeland and political power. But she opposed ethnonationalist Zionism, the kind Jabotinsky represented. She supported a homeland where Jews and Arabs lived together, not an ethnonational state. She predicted the dangers of an ethnonationalist state in Israel but never opposed Israel’s existence.

Zoe: I think this just shows why Hannah Arendt is so important. She criticised her own movement or things she was close to. People like that often get called self-hating Jews, or if they’re black, they get called Uncle Tom. I actually don’t always agree with her. Reading her work can be uncomfortable because her criticisms—like in Zionism Reconsidered—are sometimes used today by violent people who are antisemitic. Antisemites love when someone within the group agrees with them, saying, “See, Jews also hate Israel or Zionism.” They use her arguments. That was people’s issue with her during the Eichmann trial too, but she stayed true to what she believed in. She was very brave.

Roger Berkowitz: That’s who she is—brave and bold. I always say what I love about Arendt is that she’s a provocative thinker. As a woman, she took on male establishments; as a Jew, she took on the Jewish establishment; as an academic, she took on the academic world. She’s a freethinker. On Zionism, in Origins of Totalitarianism, she argued that Jews lacked experience with power because they never had a state. That lack of power made them vulnerable. She believed Jews needed a homeland and to learn to wield power. But she thought an ethnonationalist state would lead to tragedy—and sadly, she was right.

It’s complicated because today, anti-Zionists sometimes parade her out as someone who predicted Israel would become a racist state. They’re not wrong. She did foresee some of what’s happening now, but she wasn’t an anti-Zionist. She always believed in the need for a Jewish homeland; she just opposed the ethnonationalist version of Zionism.

Zoe: She was all for pluralism and diversity, and she loved that. And that’s why she didn’t think Israel should be an ethnonationalist state. Even though Israel is Jewish, Jews are so diverse—black Jews, white Jews, Asian Jews, and so on. But was she being idealistic or utopian in thinking Jews and Arabs could live together? I feel like Jews have shown they can live with others, but it’s often others who can’t live with them.

Roger Berkowitz: It’s a great question. Arendt wasn’t a politician; she was a thinker. She stood outside politics and commented on it, and she supported the labour Zionist idea of Jews and Arabs living together. Could it have worked in the 1920s and 30s if the right leaders had brought them together? Maybe.

But by 1945 and 46, she realised it was no longer possible. Jabotinsky’s ethnonationalist strain had won. She wasn’t an idealist anymore at that point; she was a realist. She saw tragedy coming. I think she might say, “This is unjust on both sides, but I’m a Jew and I pick my side.” That’s the complicated answer she might give. She’d say, “I don’t think Israel is always just, but I’m on the side of the Jews.”

And I agree with her. I don’t think Israel is always just, but I’m biased, I’m prejudiced. I’m a Jew, and I think Jews need to protect Jews. That doesn’t mean I condone racism. I’m deeply critical of racist Jews, just like I am of people like Hamas. Unfortunately, right now, the horrible people seem to be in control on both sides.

Zoe: Definitely. And I’ve lost quite a few friends, mostly female friends, since October 7th. Many of them were white, but I also lost a close French-Algerian friend. It hurts that we’re not friends anymore, but I understood it—of course, she’d be pro-Palestinian.

Roger Berkowitz: But why couldn’t you talk and find common ground?

Zoe: I don’t know. We just couldn’t talk about it. It was very upsetting losing that friendship.

Roger Berkowitz: Arendt wrote about this in her correspondence with Gershom Scholem, the Jewish scholar. After Zionism Reconsidered and her Eichmann trial work, he criticised her heavily. She wrote to him, “I hope we can still be friends, but I’m not sure if you can do that because you’re a man who’s used to getting his way.” For her, friendship was about being able to disagree violently but still maintain respect. She wrote that friendship happens on the knife’s edge, where we can almost hate each other yet still respect each other. That’s a central part of her thinking, and it relates to politics. Politics for her isn’t about love; it’s about learning to disagree while finding the common ground.

Zoe: That’s a great insight—connecting friendship and politics. I think we’ll need another discussion about this, but to wrap up, I’d love to do some rapid-fire questions if you’re okay with that. Did Hannah Arendt see Jews as a tribe? How did she view Judaism?

Roger Berkowitz: That’s a great question. At one point, she said the glory of Jews was their belief in God and their humility. But today, too many Jews see themselves as a tribe. She didn’t think Jews should be ethno-tribal. She had a group of friends she called a tribe, but it included Jews and non-Jews. For her, being Jewish was a fact of life, not the central fact. But when others made it central, she didn’t retreat from it.

Zoe: What about her gender? Did she talk about being a woman?

Roger Berkowitz: She often said she wasn’t a feminist. She didn’t embrace feminist ideology. But she recognised that some men, like Scholem, couldn’t stand that she didn’t bow to them as a woman. She was clear that being a woman gave her certain disadvantages, but she never tried to change that. And even though she was much more famous than her husband, Heinrich Blücher, when people came over, she’d still put on an apron and cook.

Zoe: That’s so intriguing about her. I watched her interview on German TV with Gunther Gauss. She captivated me. She wasn’t conventionally attractive, but there was something so charming about her. She opened that interview by talking about her gender and said something like, “It’s not a good world for women.” Do you remember?

Hannah Arendt speaks about womanhood. Full interview here.

Roger Berkowitz: Yes, she said something like, “I’m a woman, and that has given me both advantages and disadvantages.” But she didn’t embrace feminism. And by the way, when she was younger, she was quite beautiful. She had an affair with Martin Heidegger, and men all over the world were drawn to her because of her charisma.

Zoe: Yes, she was beautiful. And her charm—that cigarette she smoked in interviews—she was so captivating.

Roger Berkowitz: Absolutely. She had charisma, or what people now call “rizz.” And she smoked. She was feminine in a traditional way, but also intellectually powerful, which both captivated and offended people.

Zoe: Did she ever talk about not having children?

Roger Berkowitz: Maybe once or twice. But she was a refugee from 1933 until 1950. She didn’t feel stable until she was in her 40s. I don’t think having children was something she desperately wanted, but her life circumstances didn’t allow for it.

Zoe: That makes sense. Well, I think we should finish up here, but can you tell our listeners a bit about what you do at the Arendt Center?

Roger Berkowitz: Sure! The Hannah Arendt Center isn’t a mausoleum for Arendt. It’s not just for people doing research on her. We try, in her spirit, to talk about the world in a provocative, bold way. Every Friday afternoon, we have a virtual reading group where we go through Arendt’s books chapter by chapter. It’s grown into an amazing intellectual community. We also have an annual conference, this year on Tribalism and Cosmopolitanism, which will be on October 17th and 18th at Bard College and livestreamed. We have a podcast called Reading Hannah Arendt, and we publish a journal once a year.

Zoe: Lovely. Thank you so much for joining me, Roger. And thank you for keeping Hannah’s work and thoughts alive.

Roger Berkowitz: Thank you, Zoe. I think her work is deeply relevant today, but it’s challenging. We try to make sure people read her not because she’ll support their views but because she’ll make them think.

Zoe: Exactly. Thanks again.

Roger Berkowitz: Thank you, Zoe.