Podcast

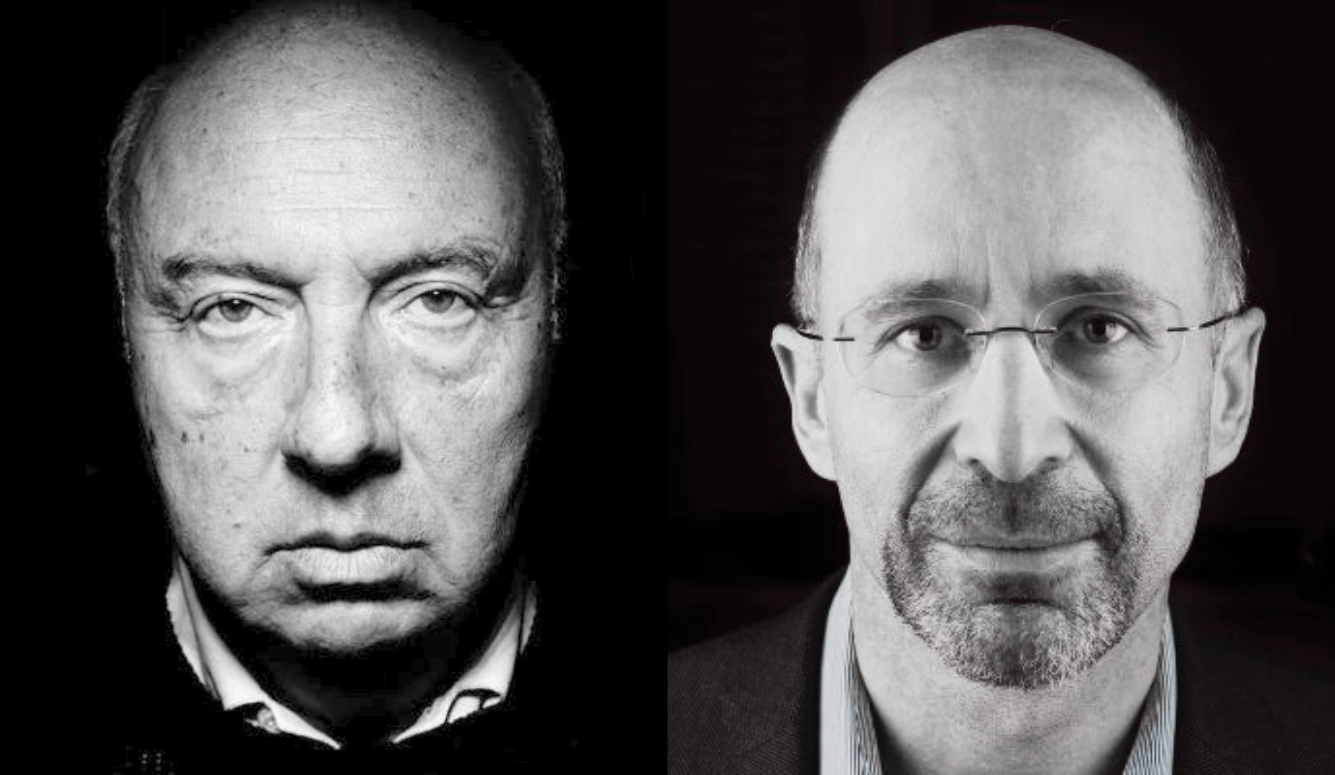

Oikophobia and the Crisis of Western Democracy with Shany Mor | Quillette Cetera Ep. 62

An Israeli former National Security Council official examines Australia’s anti-Israel protests, the rise of antizionism in Western academia, and the growing crisis of democratic confidence across the West.

In this episode of Quillette Cetera, Zoe Booth speaks with Israeli political thinker and writer Shany Mor, who previously served as Director for Foreign Policy at Israel’s National Security Council. A prominent commentator on democracy, nationalism, and Western political culture, Mor writes widely on Israel, anti-Semitism, and the crisis of the liberal order.

They begin with Australia’s recent anti-Israel protests and the country’s growing reputation abroad, before widening the discussion to the deeper intellectual and cultural forces driving contemporary anti-Semitism in the West. Mor argues that antizionism today reflects not merely foreign conflict, but a crisis of meaning within Western societies — shaped by guilt, identity politics, and what he calls a new moral accounting.

The conversation ranges from 9/11 and campus radicalism to demographic decline, democratic instability, and the fragile legacy of the post-war order — asking whether the liberal consensus of the late 20th century was the norm, or the exception.

Zoe Booth: Shany, thank you so much for joining me today.

Shany Mor: My pleasure to be here.

ZB: I was wondering if Australia has been in the news much in Israel with the recent visit of President Isaac Herzog to Australia. We’ve had huge protests—unfortunately very, very violent protests—perhaps the most violent clashes between protesters and police that we’ve seen in Australia’s history.

From what I hear outside Australia, Australia is developing quite a bad or notorious reputation as being an island that’s so hostile towards Jews and Zionists. Have you heard much about it in Israel?

SM: Well, I should say two things about it. One is that it’s got a lot less attention than you might think. Those things exist and loom large in the Jewish world—perhaps for Israelis much less. Very little of it makes sense, and very little of it coheres into any kind of domestic political story.

In particular, the thing that is almost taken as a given in the community of obsessive Israel-haters—which is that Isaac Herzog, of all people, incited genocide—that he incited genocide by giving a speech in English about the importance of respecting civilians’ non-combatant status, and answered a question from a reporter about whether Hamas was just a terrorist organisation by saying, well no, it’s actually the governing structure of a state-like entity, and that it’s an entire nation there that was responsible—in the sense, clearly in context, that he’s saying not just a weird terrorist organisation—that this is somehow taken as a given that makes him—Herzog, a man in Israel who’s noted mostly for his high-pitched, nasally voice and gentle manners—that this makes him in the category of criminals together with the people who murdered six million Jews in Europe in the 1940s—it doesn’t even register. It’s such a level of absurdity that I don’t think anybody here could possibly comprehend it.

Again, in the world of anti-Israel activism, it’s huge. And in the world of Jews who are caring about this and dealing with this, it looms large. It doesn’t really have any resonance for Israelis. It’s so highly improbable. It makes no sense.

The visit itself received some coverage. Obviously, so did the protests. Do Israelis have an understanding of the institutional capture of Australian intellectual life—or left-liberal Australian intellectual life in particular—in the academy and in the world of NGOs by a kind of obsessive and fanatical hatred of Israel and Jews? I don’t think that that has penetrated here in any real sense.

ZB: That’s good to know, actually. I’m relieved to know that Israelis seem, yes, unfazed by so many things that diaspora Jews and their supporters are faced with. They’re always a source of inspiration for me.

SM: It just also has to do with the provincialism of the Israeli opinion market. I mean, for most Israelis there’s really only one foreign country, and it’s English-speaking, and it’s also across an ocean—but that’s about as far as the general interest is going to go.

ZB: So if those protests were to happen in the States, Israelis would be a lot more concerned?

SM: Sure. And if the claims of the protesters made minimal sense, that would probably get attention. Again, the idea that this mild-mannered head of state—which is not an executive position here—had incited genocide in English, in a speech about the importance of respecting non-combatants, is…

I mean, it’s just so stupid. It’s hard to even convey to people. And yet, if you go online or look at the so-called experts in the genocide studies field, this is something that’s bandied about as though it were true.

ZB: Yes, and we should get into that—into the genocide studies topic. But I just have to agree that I was there at the Isaac Herzog event, and essentially the only reason I bought a ticket was because of the Streisand effect. These protesters and activists made such noise about it that I paid for a ticket to see a man who, by all accounts, is pretty boring.

Not a particularly inspiring or interesting orator, really, but I was there to show support.

SM: Fundamentally, what we’ve seen in public life in Australia—and not just in public life, but on Bondi Beach as well—is an Australian problem, not an Israeli one.

There’s something to consider here, and it goes beyond just the Jewish community in Australia: that a liberal democracy has whipped itself up into a—I want to say quasi-religious, but it’s really just religious—hysteria about a people apart, tainted by some ineffable sin that makes them and their community at large targets for any kind of libel and violence.

ZB: Yes.

SM: I think this is something that needs to concern you much more than it needs to concern us.

ZB: Definitely, I would agree. I would question whether it’s a particularly Australian issue or just a Western issue at the moment. Although I spoke to Adam Louis-Klein, who made a good point that a lot of these postcolonial studies ideas came out of Australia—that Australian academics were really very influential in this field—and that maybe there’s something about the Australian mindset that makes us more susceptible to this sort of antisemitic… nonsense, essentially.

SM: Yes, I think there’s a larger Western problem here. I do think there’s something uniquely Australian as well. Australia and Canada have been real stars in the intellectual ferment that’s come to the fore in the last two years—but also much deeper than that.

I think a lot of this, as in other historical examples where a kind of elite antisemitism gains this kind of traction, is a cultural and intellectual anxiety that is entirely local—about entirely local issues—that’s then displaced onto Jews.

In the same way that I wouldn’t centre this around Israel, as we said when you raised the question earlier, I also wouldn’t just expand it into a question of the West. Something is definitely afoot in Australia and in Canada—both, by the way, for largely the same reasons, or the same combination of reasons: real anxiety about the fundamental morality of the national identity as it is.

On the one hand, there’s this performative renunciation of a collective historical mythology. But when it touches us—the Australians or the Canadians—it’s a performance. And then there’s a displacement, in terms of actual kinetic action, onto Israel and the local Jewish community, people who are supposed to really pay the price physically.

ZB: So a literal scapegoat—like a sacrificial figure? All the guilt of a nation is placed onto the Jew or the Zionist to be sacrificed, right? Like our colonial guilt.

SM: Yes. Not only is the guilt supposed to be sacrificed, but the moral credit of Western sin is somehow transferred—in this great accounting fraud, as I’ve referred to it elsewhere—onto people who were neither victims of the West’s great sins of imperialism, chattel slavery, or the Holocaust, and in many cases were active participants in those crimes, and who continued them long after the West abandoned them.

Anyway, this is a different topic which we could expand on as well, but—

ZB: Wait—who are we talking about?

SM: Well, the Arab Muslim world had the least penetration of Western colonialism of any part of the Americas, Asia, or Africa. It was the last place in the world to finally abandon African slavery. It’s the place whose entire language and religious practices are based on an expansionist and imperial presence, and for far longer than anywhere else in the world.

The firmest believers in the kind of murderous antisemitism that plagued Europe in the last century. And yet the moral credit that is supposed to be accrued by these cosmic Western crimes of imperialism, chattel slavery, and the Holocaust is somehow transferred to them.

ZB: In the hierarchy of identity politics—of, I suppose, noble savages whom the Left really holds in esteem—I thought it had a lot to do with literal melanin in your skin. Like Sub-Saharan Africans would be held up higher than Muslims...

SM: No, I disagree. It has to do with who is the enemy of the West. It has to do with who is the enemy.

Do you think all the leftists who were so engaged in Russian culture and Marxist–Leninist thought in the 1950s and ’60s were genuinely motivated by ideological Marxism? No. That was who the West’s enemy was.

And since 2001 especially—but really from 1989 you can see the beginnings of this—but especially since 2001, anybody who hates their own society, living in the West, who is convinced that their society is touched by sin, that there’s something irredeemably morally wrong with their society, is drawn to that.

ZB: Oikophobia.

SM: Yes, I’ve heard that word.

ZB: It’s a good one. It hasn’t quite caught on yet.

SM: No, it’s a really ugly word. It’s not particularly euphonious.

ZB: It sounds like a Greek yoghurt brand. Or an anti-Greek yoghurt brand. Have you read Pascal Bruckner’s work on The Tyranny of Guilt?

SM: Yes—from ten or fifteen years ago at least. Yes.

ZB: Yes, I think it was around 2014. That really stuck with me because it was the first time this oikophobia had been explained to me in a way that made sense. I’d always sensed it—I’d felt it. I was fully on board with it. I hated the West and I hated Australia and I hated aspects of who I was and my family and our history and everything when I was a teenager.

I’ve talked about it a bit in other podcasts, but I wanted to put my money where my mouth was and find the community most in need of my saving. Islamophobia and Muslims I deemed to be the most in need, so that’s who I chose to volunteer with. I didn’t choose an animal sanctuary or anything—I chose the Muslim community, newly arrived refugees from Syria and Afghanistan. So I was very oikophobic.

SM: There’s nothing wrong with a critical look at one’s own history, and there’s certainly much to be critical of and much to want to re-examine. We in the West live lives of extraordinary privilege in any kind of global comparison—although the gaps are much smaller today than they were, say, twenty or thirty years ago, and certainly than they were a century ago. There’s absolutely nothing wrong with that impulse or with that desire to come to terms with these things.

I don’t think there’s anything wrong with that. I think there’s a serious discussion to be had about all three of those matters that plague us.

Where I think the discussion goes wrong—I would illustrate it as a three-part, three-stage discussion.

The first stage is the identification of a kind of moral debt with, as I said, Western imperialism, chattel slavery, and the Shoah—which I think has problematic aspects, to be sure. If it becomes the totality of our historical consciousness, then we’re doing ourselves a massive injustice. But to try to place our own good fortune—being alive in the places where you and I live, at the time we live—in historical context for all of its good and ill, I don’t think there’s anything wrong with that. It can certainly go wrong. But that’s the first stage: possibly problematic, but mostly quite reasonable.

The second stage is a lot more problematic. That’s this moral accounting that essentially says we can hand out moral credit based on these perceived cosmic sins. And that credit essentially creates a sort of moral affirmative action, where if you were a victim, you get to be judged by an entirely different standard, or can make all sorts of demands and excuses for what would, in any other context, be seen as manifestly unacceptable behaviour or politics.

I think that second stage is really problematic, although not entirely. There are some very complex political situations in the world where nothing can be divorced from its history. There’s a simplistic attitude to this that I certainly don’t subscribe to.

The third stage is the one that I think is, as I said, almost hilarious. It’s that not only are there these cosmic sins—which I think is historically limiting, though sometimes helpful—and not only do they create a kind of moral ledger—which I don’t think is a good way to go, but maybe has some internal logic—but that we can redistribute those debts, not to the actual victims of these Western sins, but to the people whom the West believes today are its biggest enemies.

That part is ridiculous to me. I mean, it’s insane. It has been the centrepiece of every form of international political morality suggested by the mainstream of left-wing intellectuals since 2001—in many ways since well before 2001. 9/11.

ZB: Why did you say 2001? Say more about that.

SM: So what do you talk about on 11 September every year in Australia? Because when I look at the media in the UK and in the United States, 9/11—every 11 September—is the anniversary of the day we talk about Islamophobia.

I was a teenager in California, and there was a bubble of right-wing, anti-immigrant hysteria in the mid-1990s.

ZB: Anti-Mexican...

SM: Yes. And when we would organise protests against this stuff, we always made sure to have signs in English and Spanish. Part of that was practical, because part of our intended audience didn’t really know English very well. But mostly that was a sign of respect—more than just a sign of respect. It was a sign of who we were.

By putting Spanish on our signs, we were saying something about what it meant to be in the community of the good when this was the issue—what it meant to be standing up to the bad guys. So it wasn’t enough just to have a slogan. For example, we would put on our signs: “No one is illegal. Nadie es ilegal.”

Then I was back in Israel for a couple of years. I happened to be living in Israel during 9/11. But then I came to graduate school in the US, and I was now in New York, post-9/11. I would go to left-wing events and so on. The slogans were the same slogans, right? Except now, instead of it saying “No one is illegal, Nadie es ilegal” and having everything in Spanish, things were in Arabic too.

The only thing that had happened was 9/11.

And there weren’t a lot of poor, downtrodden Arabic speakers in New York who didn’t know English. This was not Germany in 2015. New York was not a city that had a large number of Arabic speakers who couldn’t function in English. It was a signal. It was a way of saying: this is who we are. This is what it means to be the good guys right now.

9/11 meant, for the activist Left in a post-Soviet reality, that what it meant to be the good guys was to have things in Arabic.

Then I came to the US again many years later. The only other time I lived in the US as an adult was twenty years later. I was doing a postdoc, and it happened to be the beginning of the Trump era. I was in Providence, Rhode Island.

The resistance—as it styled itself—was very focused in its initial days on the issue of gender.

ZB: Pink pussy hats.

SM: Exactly. It was a really brief bubble, actually, which I would love to expand on, because I think there’s something fascinating about that intellectual moment in American life. But it was very briefly focused on gender. And the icon of this—at least where I was, in this liberal Northeastern university town—was a picture of a woman in a hijab.

And I thought: how is this a feminist icon?

I should say about myself—I’m realising this as I’m telling both of these stories, about my young adult self in 2003 and my slightly more grizzled adult self in 2017—that I can describe myself as dissenting from people and disagreeing with them. And I did, by the way. But I’m no hero. I didn’t publicly challenge any of this. I made a few comments, perhaps, but I was very discreet. I also wanted to be on the side of the good people.

But I would look at this and wonder. It was like falling asleep and then waking up and discovering that this is now a feminist symbol. I didn’t get it.

ZB: So you realised at the time that you weren’t on board, but you didn’t say anything because you didn’t want to ostracise yourself from the group?

SM: I wasn’t on board even in 2003. I was not on board with any of these things. They struck me as ridiculous. But no, I didn’t make a fuss.

I was struck by how, in a left-wing space in 2003, Arabic language and imagery had replaced Spanish as the cool foreign thing we would use to signal that we were good. But I didn’t make a fuss about it. And in 2017, I was really struck by the hijab. But it’s not for me to make a fuss.

ZB: Yes.

SM: I’m a Jewish Israeli guy, and nobody wants to hear—understandably, I suppose. I’m the last person who would be considered to have any moral authority to tell people that this is insane.

ZB: Even though it’s probably your Israeliness or your Jewishness that made you realise far earlier than some other people—like myself, for example—that Islam is not a religion of peace for anyone, let alone a bastion of freedom for women.

Actually, it was through volunteering with Muslim families and finishing meals with them—which were often really great meals, I must say. But then the little boys would go off and play, and the little girls, regardless of their age—five or six years old, just little kids—they could not go and play with their brothers. They would have to stay and sweep the floor and clean the tables. And cracks started appearing then.

SM: That was the reality in most families, regardless of their religion, until shockingly recently.

I would say—and it’s funny that you mention that—because usually when I say that the introduction of Islam in such huge numbers into Europe or the West in general is the second biggest social transformation of the last century—obviously the biggest social transformation of the last century is the full emancipation of women—I don’t think we’ve actually come to grips with how dramatic either of those things are.

We certainly haven’t come to grips at all with how dramatic the second one is.

And the people who have occasionally led the discussion on the second one—some of them are deeply unpleasant people whom we don’t actually want to introduce into polite company. For the last twenty years, a lot of that discussion has been led by far-right figures, often very openly racist. And I don’t think that’s done much to advance it.

The second place that’s been leading that discussion—perhaps not quite as disreputable—still believes somehow that it’s reversible. Reversible, or in some way assimilable. That this is something the West can digest and, when it’s done, be itself again—whatever that means.

And it’s not. It’s not reversible.

ZB: These are the people urging deportations, or who—

SM: Yes. There aren’t going to be deportations, though. The deportation fantasy is the unpleasant aspect. The more pleasant version of the deportation fantasy is: okay, this is an immigrant group that’s assimilating. Give it twenty or thirty years, they’ll be just like all of us.

I don’t think this is something that’s going to be digested and incorporated in the way that either a deportation fantasy or an assimilation fantasy would have us believe.

This is not a reversible thing.

ZB: I agree. I agree. But at the same time, I think it was Razib Khan who tweeted about this—that Muslims do have a higher rate of leaving the religion than Jews, for example, or other religions. But at the same time, they appear to have higher levels of radicalisation as well.

A lot of the issues in Australia—and in Canada, I believe—with young radical Muslim men: they’re not boys or men who came to Australia at twenty or something. They were born here. Naveed Akram, who shot up the Hanukkah event down the road from me, was born here. He went to a normal Aussie school in the western suburbs of Sydney, which skews heavily Muslim but also has a lot of Vietnamese and Polynesian students.

He was Australian, and he became radicalised in Australia. There’s more to learn about him and how that came to be, but yes—many Muslims may leave the fold, but they also come back into it very radically.

SM: The issue here isn’t demographic, and it isn’t a Muslim one. The issue here is a Western one.

Look, somebody comes from a non-Western society as an immigrant into a Western society, and chances are they have very retrograde views about four groups of people: blacks, women, gays, and Jews.

Now, there are two processes that happen regarding the first three kinds of prejudice.

One is an intergenerational process. You move from a non-Western society to a Western society and have all sorts of horrible ideas in your head about blacks, women, and gays. Chances are your kids—who are socialised and educated in the local public school, watching local television, making friends with locals—will have much more liberal views than you do. That’s just a natural process between generations.

There’s something even more interesting that happens, by the way. Even you yourself—even if you deny it—over years of living in a Western country, even if all your friends are from your own immigrant community, without you controlling it, your views on those issues will liberalise. It’s almost a natural process that you can’t stop, even if you made an effort to stop it.

ZB: That seems pretty normal.

Do you think it would happen in reverse? If I moved to, say, Tunisia, would I develop stronger views just from being around people?

SM: I think if you moved anywhere, you would. Of course our ideas are shaped by our social interactions. That’s natural. And it’s part of why certain social interactions are so toxic.

I can give you an example from here. Part of why I oppose the West Bank settler enterprise in Israel is because I think it creates a kind of social interaction that brings out the absolute worst instincts that already exist here. It also has a selection mechanism: it attracts some of the worst people in Israeli society to go and settle there and live out this fantasy.

But let’s put that aside.

If you come to a Western society with retrograde views about blacks, women, and gays, your socialisation in that society will moderate those views, whether you want it to or not. At first, you may be hypocritical and pretend to have more liberal views because of the social costs. But eventually even that pretending will take its toll, and your views will moderate.

If you come to a Western society with retrograde views about Jews, not only will your views not moderate—and not only will your children’s views not moderate—but the children who go into elite academic institutions will have those prejudices nurtured. What begins as a silly prejudice from home becomes fully ideologised and systematised into a progressive worldview.

You often see that the children of immigrants from the Muslim world in Britain, Canada, and Australia take what was a series of silly prejudices they heard at home and turn it into a fully formed, comprehensive doctrine.

And their Western peers treat it not as a pathology—the way they would treat prejudice about women, gays, or blacks—but as a sign of authenticity. It can even become a card to academic and professional promotion.

The murderers who killed fifteen people on Bondi Beach did it following two years of Australian elites—who are not immigrants, not Muslims—repeating the same grievances and lies about Israel and the Jewish people, turning that into something legitimate.

Then they’re shocked. “We’re against violence. We don’t think Jews should be held accountable for…” It’s like saying, “We don’t think Jews should be held accountable for the crime of deicide, which we condemn.”

But everybody in Australia who spent the last two years repeating verifiable lies about genocide, about starvation—

By the way, you’re in media. One of the things that struck me when I lived in Britain was reading war coverage in the local press. There were many wars in the world. But only when there was a war involving Israel—whether in Lebanon, the West Bank, or Gaza—did death tolls include the number of children.

ZB: Yes.

SM: I never saw that for any other war. “So-and-so number of people were killed in fighting today, including at least eighty children”—often numbers that were completely made up.

That is part of a daily drip.

ZB: Women and children. Yes, I saw Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez today say something in Munich at a Holocaust remembrance—I don’t know, it was disgusting—but she said “the genocide of women and children.” And it just stood out so much to me. I mean, I’ve heard it so much, but it just seems so forced. Why not just say people? Why the focus on women and children? It was so—

SM: The focus on children is a huge part of this. And the idea of Jews committing ritual slaughter of children has a deep, deep genealogy.

ZB: Yes. This is reminding me—have you seen Bret Stephens recently? It was good. In summary, he pretty much said that after the multi-million dollar Super Bowl ad to combat antisemitism—yes, it’s great to try to combat antisemitism, but frankly it doesn’t work that well. People have always hated Jews; they’ll always hate Jews. There was Jew-hatred even before Christianity.

So what we should really be focusing on is uplifting and strengthening Jews themselves—making Jews great again, essentially. Focusing on Jewish learning and Jewish children. There was some mention of not marrying out so much.

That made a lot of sense to me, because I’ve been trying very hard to share all the knowledge I’ve learned about Jews and Israel since 7 October. I didn’t grow up Jewish. I didn’t know any Jewish people. I’ve been obsessed with learning—and I hate the term—but “unlearning” so much of the propaganda I’d absorbed.

I’m so passionate about it, and I just think everyone else must be equally passionate about the truth—like, wow, isn’t this interesting? But people don’t give a shit. They don’t care. You can say, “A Jew came up with the vaccine for polio.” No one cares. They know that. They don’t care. It’s not rational.

SM: Sure. But it’s hard to sustain a community and an education when all of your resources are poured into security. We’ve seen that in the last 25 years in European Jewish communities. We’re probably going to see that now in Australia and Canada, and even in the US.

The entire endeavour of sustaining Jewish cultural and ethical life is really hard when it has to be done behind armed guards and fences.

Even if you ignore the cost, the psychic cost of that is very high. It’ll be hard for people who aren’t hugely committed to want that. Why would you?

And that’s happening against a background of what is basically a purge of Jews from intellectual and academic life—unless, of course, they engage in ritual self-denunciations.

ZB: Have you experienced that as an Israeli academic, as a Jewish academic?

SM: Look… of course I’ve experienced it throughout every academic endeavour I’ve been part of.

What I’ve not done is put myself up for this ritual self-denunciation. I’ve had plenty of colleagues who did—many of whom clearly didn’t believe what they were saying. Not just post-7 October. I’m talking about the last twenty years or more.

Parts of the academy were already locked—sealed off from Jews who weren’t part of the micro-minority of denouncers of their own community. And that small part of the academy that was sealed off has expanded greatly in the last ten years.

ZB: Do you have any comments on this oikophobia—or Western self-hatred—being something that comes from religious roots? From Christian theology? Or before that, maybe a Judeo-Christian tradition?

SM: I think the rituals of anti-Zionism—its basic moral commitments, its idea of sin being transmitted through the generations, of ineffaceable guilt—have a very obvious Christian genealogy.

Much of our moral politics in the West draws directly from these practices. Religion hasn’t gone away.

The environmental movement, in particular, loves this stuff. You’re a sinner for flying. You can pay indulgences in the form of carbon offsets. If something feels good or convenient, it must be making you impure, which you then need to fix later.

And all of this is happening at a supposedly secular time. As I’ve written elsewhere, somewhat sarcastically, at least church classicism gave us beautiful stained-glass windows and ethereal music. I don’t know what the current theological fervour is going to leave us with.

The fact of the matter is that people need these stories and myths for any kind of meaning.

ZB: I assume you say that as not being an observant Jew yourself—or maybe you are, I’m not sure. Or religious? You don’t have that vibe.

SM: I’m not observant, no. But that doesn’t mean I live a life of emptiness, nihilism, and no meaning.

It’s a bit awkward for me to be telling people not even about the religion I don’t believe in, but about another religion that isn’t mine and that I don’t believe in, that I sometimes wish they would just go to church and shut up.

ZB: I’m feeling more and more like that. I’m very pro-Christian.

SM: Our cultural lives are like our language. Our stories are our only way of processing our interactions and communicating with each other. Our stories, our images—it’s impossible to exist in a culture and not operate within its myths, its images, its enduring protagonists.

The fact that people stopped getting up on Sunday mornings to hear sermons about implausibly unscientific stories hasn’t removed them from those larger myths at all—including from some of the less savoury sides of them that they indulge in.

ZB: Fascinating.

I’m very interested in this topic of babies at the moment. I’ve been baby-pilled and hopefully will be having my own quite soon. Israel is one of the—well, I believe the only—developed OECD nation that actually has a healthy replacement-level total fertility rate.

People say, “It’s just religious Jews.” No, it’s secular Israelis as well.

I think Australia’s low fertility rate is due to a number of factors—economic factors. But also I think deep down there is a lack of desire to reproduce. Like, what’s the point of it all? There is a nihilism, a lack of belief.

So yes—do you have any comments on that, and why Israel has a healthy fertility rate?

SM: It’s a rather complex subject. Nobody really knows why fertility rates have dropped so precipitously around the world in the last fifteen years.

It’s very easy for anyone to tie this to a politics they’re already predisposed to believe in. It’s very easy for me, as an Israeli, to tie it to the idea that this is just one more measure in which Israel is extraordinary—so hooray for us.

But the fact is, fertility has been declining in poor countries, rich countries, Christian countries, Muslim countries, northern countries, southern countries, equatorial countries, cold countries, warm countries, countries with generous welfare states, countries with weak welfare states.

Something is happening there that I don’t have an adequate explanation for.

To believe in something larger than oneself—to seek a life with meaning rather than merely subjective happiness—can’t really lead you anywhere else. This essential part of life that we’re programmed to want doesn’t have much rational purpose in a wealthy modern welfare state.

I suppose a big part of the Israeli exception is that life here, regardless of whether you’re a believer or not, has meaning.

It’s just inescapable.

There’s a lot of material and aesthetic dullness here. Middle-class life in Israel isn’t as luxurious as it is in much of the West. Our flats are smaller. Our climate is more unforgiving. You put up with a lot of frustration in daily life—and a lot of danger. You put up with bad customer service.

But life has meaning.

I don’t know how to quantify that or positively identify it.

The push to have families is always going to be higher—or is necessarily going to be higher—in a conflict zone. And of course, for Israelis, it also ties to a certain kind of post-Holocaust sensibility.

But I don’t have an overarching scientific theory for why things are different here than in other countries. If I began to indulge in one, I’d probably just be indulging my own political prejudices.

I would also say that fertility rate is not always the best measure of these things. It measures one thing, but population trajectories depend on age of reproduction and other demographic factors.

People’s desire to have families and the size of those families is responsive to a whole range of incentives.

There’s a study in the US that looked at states that had mandatory child seats up to a very late age versus those that didn’t. It found a correlation with fertility rates. States that mandated child seats up to age eight or nine had families stopping at two children. States that didn’t had many more families with three children.

But economic incentives clearly aren’t the whole story. Social pressures are a big part of it. When you’re in a place where other people are having children, you’re more likely to have them. When you’re in a place where nobody is, you’re more likely to skip it.

There’s a contagion effect. I think that’s happened a lot in the West since 2008.

ZB: There’s a lot of talk here that it’s due to houses getting smaller, or people only being able to afford apartments. I think that’s definitely part of it. But at the same time, I was just in Vietnam and people there live with their grandparents in very small, multi-generational housing—what we would consider very humble—and they’re still having children.

Interestingly, they still only have two children because that was imposed on them by...

SM: ...the Communist regime.

ZB: Exactly.

SM: Are houses in Australia smaller today than they were fifty years ago? I doubt it very much.

ZB: I think more people are living in high-density apartments, but yes, I don’t think that’s the best argument. It depends what your peers and your parents had. If your parents had a house and you only have an apartment, perhaps it feels like downward pressure.

SM: I’ll say this: nobody who doesn’t want children should be having children. Nobody who’s not ready for it should be having them. There are a lot of bad parents out there.

ZB: Yes, that’s true.

So, you write a lot about democracy. What are your thoughts on democracy at the moment? We’ve already talked about mistruths and lies spreading, and it seems to me—and I think studies back this up—that people simply don’t care that much about the truth. Humans overestimate their own commitment to the truth. How does that affect democracy?

SM: The thing that’s really concerning me in the last decade or so in mature democratic countries is that our elections have become referendums on the constitution itself each time. I don’t think this is sustainable.

The point of an election in a mature democracy at peace is to choose between two reasonable options. It’s unpleasant when your side loses. It’s sad for a day or two. That’s normal. But that needs to be it.

The situation we now find ourselves in, in so many democracies—including the one I’m sitting in right now—is that the election feels like a life-or-death reckoning. Losing doesn’t just mean that the people you like less are going to be in power for the next three or four years. It feels like the end.

When that is iterated over multiple election cycles, I don’t think that level of tension is sustainable.

That’s where we are in Israel. It’s where we were in the United States. It’s where we were in Britain and in France. I don’t think this is a normal state of affairs, and yet it now seems standard in country after country.

For much of the post-war period, in most mature democracies you had a choice between something that looked like Christian Democrats and something that looked like Social Democrats. These were moderate parties that had different positions on major cultural and social issues, but fundamentally believed in the constitutional order, in the rule of law, and in a basic set of civil rights guaranteed to all citizens.

They fought back and forth. They lost power from time to time. They spent time in opposition. Occasionally someone would be caught in corruption and even go to prison. But more or less, that was how the system functioned.

It’s been falling apart for about thirty years—first gradually, and then since around 2015, very quickly.

If you look across the landscape, you don’t see many authentically Christian Democratic or Social Democratic parties any more. There are very few countries where you still see both.

The United States hasn’t had a functioning Christian Democratic-style party since the 1990s. The Republican Party turned into something else. Israel hasn’t had one for at least ten years—probably more.

ZB: Why is the Christian aspect important?

SM: I’m using “Christian Democratic” in a descriptive sense—a party that believed in real social solidarity, national purpose, universal civil rights, and a collective mission for society, but with different emphases from their left-wing counterparts.

They believed more strongly in the free market, in personal responsibility, in the importance of the family unit. They were culturally traditional. But they operated within a constitutional consensus.

That began to fray in the US in the 1990s, and in Europe perhaps a bit later.

On the left, the picture is similar. The social democratic consensus began to fall apart in the 1970s and ’80s. What replaced it on both the left and the right is what I call the great privatisation of politics—highly individualist politics, very adversarial.

ZB: For example?

SM: The whole rights-based discourse of left-wing politics since the 1970s—a discourse centred on how minorities trump democratic political processes.

ZB: Did the Vietnam War have something to do with that?

SM: In the US, yes, it had a lot to do with many things. And the economic dislocations after 1973 ripped apart the tie between the working class and the moderate Left.

The reality is that we no longer have major parties that resemble either traditional Christian Democratic parties or traditional Western Social Democratic parties.

And so we get to a point where each election becomes a referendum on democracy itself. Occasionally the result is not satisfying. And I don’t know where we go from here.

We may ultimately conclude that the liberal consensus democracy of the post-war years was the exception — and that the politics of extremism and violence, which characterised most of human politics before 1945 and increasingly characterise the 21st century, are the norm.

I hope that’s not the case. But it’s possible.

ZB: That’s scary.

And again, it reminds me of Pascal Bruckner and his writing on The Tyranny of Guilt. You said “post-war order,” but would we have had that order without the Shoah? I wonder whether we needed the Shoah in order to learn to be like that—to have those few decades of prosperity and relative pacifism.

SM: I don’t know. The Shoah is there in the background of so much of our politics and our anxieties.

But I do know that we would not have had the postwar peace and prosperity and social solidarity without the decisive military victory that the Allies achieved in 1945, and without the overwhelming military threat that the West posed to Soviet tyranny throughout that period.

Without the victory of 1945, and without standing firm against the Soviet threat, none of those things would have been possible.

At the same time, while that glory period for North Atlantic countries was happening, in much of the rest of the world life wasn’t so great. We had a lot of social equality in Western life during those decades, but it existed alongside massive global inequality that we no longer have.

That opens up other questions as well.

One of the great achievements of the last thirty years—which have been politically less glorious in Western countries—is the drastic reduction in global poverty, unlike anything we’ve seen before.

It’s not just China, although China carries enormous statistical weight because it’s so large and its gains have been so dramatic. But it’s not only China. Across much of the world, we’ve seen an astonishing near-elimination of absolute poverty that had been endemic in the human condition from time immemorial.

That’s a stunning achievement, and it shouldn’t be dismissed in our nostalgia for the post-war era.

Nor should the social reforms in the West over the last few decades be eclipsed by that nostalgia. It’s much better today to be a woman, a gay person, or an ethnic or racial minority in the West than it was in those supposed glory days of the postwar years.

A lot of the social solidarity we admire from that period existed in exclusion of very vulnerable groups within Western societies.

What we haven’t found is a formula that allows us to be inclusive domestically and globally while still holding on to that older vision of solidarity—a vision that existed in both moderate Left and moderate Right forms of politics, alternating power non-violently and in an orderly way for decades.

Until everything went to hell.

ZB: Yes.

Not to bring it back to Israel again, but I was struck when I went to Israel for the first time a few months ago that Israel seems to strike that balance quite well—having patriotism, self-belief, pride in who you are, self-respect—something Australia doesn’t seem to have—while also being fairly open and liberal.

SM: Look, the defining feature of domestic life in the last two years has been the hostages being held in Gaza.

On the one hand, the salience of that issue is indicative of a certain kind of solidarity. But on the other hand, there’s something very depressing for me as an Israeli about the political valences that the hostage issue took.

For a great deal of the Israeli Left and left-wing commentary, you would read about the hostages as though they were being held by the Israeli government, not by Hamas. The moral failure of their captivity seemed to attach to political leaders here whom they didn’t like, rather than to the sons of Satan who kidnapped these men and women from their homes after murdering their families.

For parts of the political Right, there grew to be a kind of hatred of the hostages. Instead of understanding that these were the worst victims of the Hamas massacre, they seemed genuinely to dislike them.

There were far-right activists who harassed families of hostages at protests. They seemed to see in them an embodiment of the humiliation of that military defeat we experienced on that Saturday morning.

The closest historical analogy it recalled for me was the cruelty of some Arab states towards refugees from the 1948 war—seeing them as reminders of defeat.

I’m proud that we cared about the hostages. I’m proud that we didn’t give up on them. I’m proud that we brought them home. I’m proud that we learned their names and struggled so hard to get them back—that they meant so much to us.

That says something very positive about Israeli society.

But I’m also deeply depressed by how that issue was understood by some of the most partisan elements domestically. It exposed not just something healthy and admirable, but also things that are deeply, deeply unwell.

ZB: Wow. When is the next election?

SM: The next election is supposed to be in October. It might be moved up by a few months, especially if there isn’t a compromise on the conscription bill. If that happens, it’s likely parliament will be dissolved early. But either way, the election will be this year, in 2026.

ZB: Is there anything else you’d like to talk about? I should probably wrap up—it’s getting a bit late here.

SM: No, I think we covered everything.

ZB: You’re sure?

SM: You’ll have to invite me again.

ZB: Okay. And if people want to read your work, Quillette has published one of your pieces—a book review of a book I haven’t read, but it was a good review—and hopefully we’ll publish more of your work soon.

SM: I’m looking forward to it. I really enjoy the magazine. It’s been a voice of sanity in the last two years.

ZB: Great. I agree—but I’m biased. Thanks for joining me, Shany.

SM: Thank you for having me. Bye.