Residential Schools

No Bodies, No Accountability

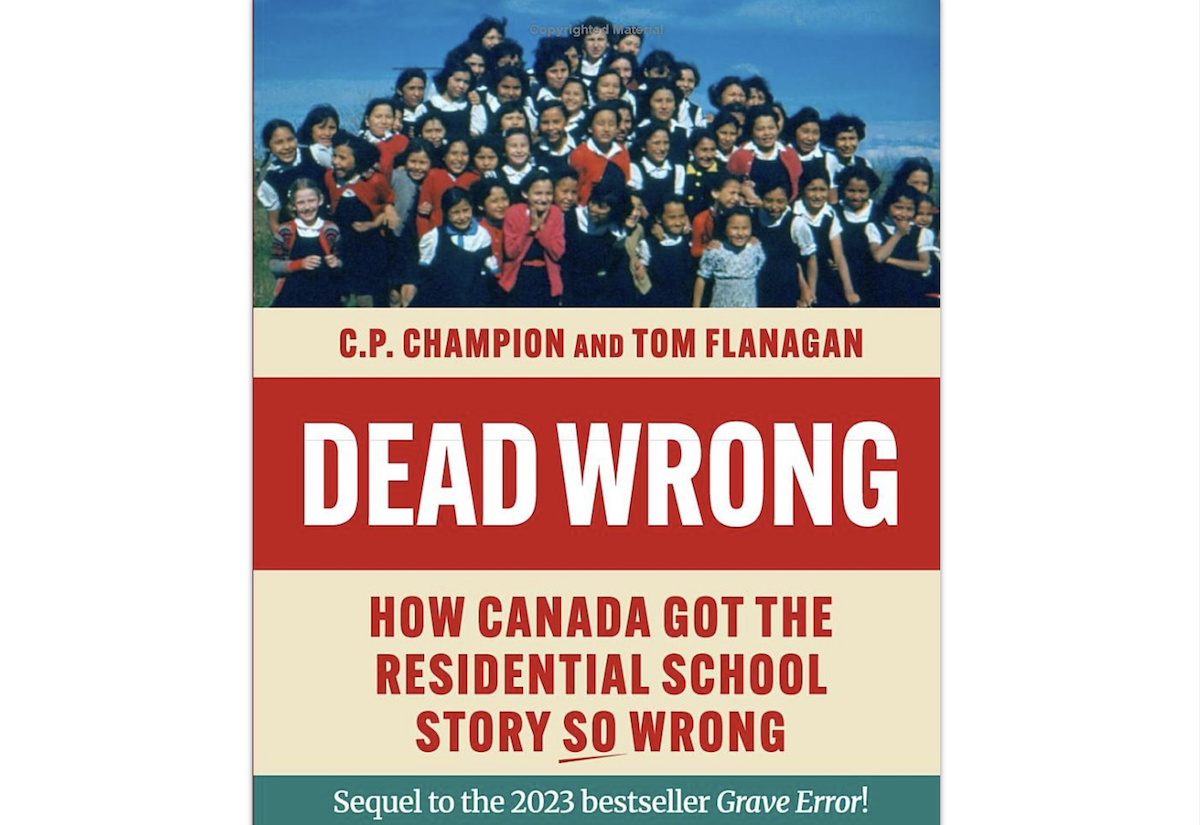

A new book catalogues the damage to Canadian society caused by a 2021 social panic over non-existent ‘unmarked graves.’

In 2023, we published Grave Error, a book of essays that candidly discusses the “unmarked-graves” social panic that swept Canada four and a half years ago. In May 2021, it was announced that ground-penetrating radar (GPR) had identified the formerly unknown resting places of 215 Indigenous children who’d attended the Kamloops Indian Residential School in British Columbia. The announcement sent shock waves through Canadian society, and led to months of self-lacerating commentary about our country’s colonial sins. Journalists and politicians alike acted as though these 215 victims—children who’d presumably been dispatched by murderous Residential School staff—had been identified and unearthed. It was only once this initial period of national hysteria ended that observers noted that, outside of the GPR reports, there existed no proof of graves, bodies, or human remains. And since GPR technology cannot detect bodies, but only soil dislocations that may equally indicate tree roots, drainage ditches, rocks, or other artefacts that have nothing to do with graves, the claim that these GPR-identified soil anomalies corresponded to graves remained unproven.

To this day, not a single grave has been discovered at any of the GPR-identified locations in Kamloops; nor at any of the other Residential-School sites where similar GPR surveys were conducted. Seen in retrospect, this whole strange episode in Canadian history now seems like a morbid farce.

All of this has been a particular embarrassment for Canadian journalists, who took a leading role in convincing readers and viewers that those 215 “unmarked graves” were real. This explains why many journalists have simply stopped talking about the issue, perhaps in the hope that the whole mortifying episode (and their role in it) will simply be forgotten.

To this day, not a single grave has been discovered at any of the GPR-identified locations. Seen in retrospect, this whole strange episode in Canadian history now seems like a morbid farce.

Thankfully, some Canadian media have mustered the courage to acknowledge that the claimed graves have never been found—including The Dorchester Review, CBC News, and the National Post. Internationally, this tale of epic gullibility has also been told in The Wall Street Journal, the New York Post, Quillette, and numerous other publications. (In 2024, The New York Times grudgingly admitted that no graves have been found, but also darkly suggested that anyone pointing this fact out is likely carrying out the work of shadowy “conservative Catholic and right-wing activists.”) While it is still considered politically taboo in progressive Canadian circles to mention that none of the graves have been shown to exist, almost two thirds of ordinary Canadians now tell pollsters that more evidence is necessary before they will accept the unmarked-graves narrative we were once all supposed to believe on faith.

Even by 2023, Canadians were clearly ready for a fact-based discussion of the unmarked-graves controversy—which explains why Grave Error instantly became a Canadian best-seller upon its publication. The book’s success is all the more notable given that it was largely ignored by mainstream journalists (largely for the reasons described above). To this day, many media outlets seem to remain vested in the idea (hope is perhaps a better word) that someone, somewhere will discover proof to back up their flawed 2021-era reporting.

In truth, there is a religious quality to the discussion of unmarked graves in some circles. For such Canadians, it seems, the martyr status of those 215 (imaginary) dead children transcends the realm of provable fact.

In the spring of 2024, the small British Columbia city of Quesnel made national news when it was learned that the mayor’s wife bought ten copies of Grave Error for distribution to friends. Following noisy protests, Quesnel’s Council voted to censure Mayor Ron Paull (who was accused of recommending this heretical literature to others), and tried to force him from office—effectively on the argument that anyone who blasphemed the religion of Indigenous reconciliation through possession of forbidden literature is unfit to serve.

Thankfully, Mayor Paull was later vindicated in the courts, and his wife, Pat Morton, is now suing the Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs for defamation. But they’ve had to endure many headaches and expenses in the process (though the whole controversy was good news for Grave Error, which spiked in popularity during this controversy).

Several Canadian public library systems refused to acquire Grave Error. Those libraries that did acquire it, such as in Vancouver, Calgary, Ottawa, and Toronto, experienced long waiting lists. Despite desperate attempts to (literally) criminalise unmarked-graves “denialism” (more on this below), people wanted to read the book.

We now invite these same readers to consider our newly published sequel to Grave Error, Dead Wrong, because the struggle for accurate information and accountability isn’t over.

As noted above, few of the journalists who took a leading role in promulgating false information on this file have admitted their errors—even those who work at blue-chip journalistic outlets that, in any other context, would be quick to correct bad reporting. As noted in Chapter Five of our new book—adapted from a Quillette article entitled, When Will The New York Times Correct Its Flawed Reporting on ‘Unmarked Graves’?—the English world’s most prestigious newspaper ran a number of absurdly counterfactual articles on this subject by a reporter named Ian Austen. One of these promoted the (especially) bizarre claim that a “mass grave” had been uncovered at Kamloops—a fable so singularly outlandish that even otherwise credulous Canadian reporters refused to repeat it. More than four years after Austen spread this misinformation, his articles remain uncorrected on the Times web site.