Art and Culture

A History of Morality Clauses

The century-old moral panics and persecutions by Anthony Comstock and the Society for the Suppression of Vice are echoed today by cancellation campaigns from the moralistic Left and Right.

In 2022, the UK government-funded Scottish Book Trust demanded that all 600 writers listed in its Live Literature directory—the primary means by which authors in Scotland are booked for speaking engagements—sign a code of conduct. That document required its signatories to pledge intolerance of bigotry in any form, including transphobia, without defining either term. Several authors protested, referring to the requirement as a morality or morals clause. The same year in Kansas, the St. Marys City Commissioner added a morality clause to the Pottawatomie Wabunsee Regional Library’s 2023 lease prohibiting the library from loaning out “explicitly sexual or racially or socially divisive material” and holding events that “support the LBGTQ[IA]+ or critical theory ideology or practice.” Eventually, the library was able to renew its lease without agreeing to the new clause. Writers in Scotland were not as lucky.

There are thoughtful conversations to be had about requiring children’s TV presenters to have no past or future criminal records, establishing appropriate age guidelines for children’s library materials, and imposing standards on the conduct of pastors. However, the resurgence of vague and poorly defined morality clauses in arts and literature over the past decade—many of which require no evidence of misbehaviour, substantiation of accusations, or anything besides a social-media mob and a publisher’s wish to sever a contract and reclaim a book advance—has shackled writers, artists, and intellectuals who require full freedom of thought and expression to do their work.

Most attempts to trace the history of morality clauses begin with Universal Pictures’ 1921 requirement that actors and actresses “conduct [themselves] with due regard to public conventions and morals and … not do or commit anything tending to degrade [themselves] in society or bring [them] into public hatred, contempt, scorn, or ridicule...” As Universal’s attorneys stated, the introduction of this language was a response to the arrest of actor Fatty Arbuckle on rape and murder charges, of which he was later acquitted. However, as I note in my third book, Break, Blow, Burn, and Make, morality clauses date back to at least 1914 in the US. They were publishers’ corporate response to the persecutions and prosecutions of a fanatical religious reformer named Anthony Comstock, who was funded by wealthy magnates like J. Pierpont Morgan and Samuel Colgate through the YMCA and its offshoot, the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice.

Comstock was a complicated man. It can be said in his favour that he lived according to his own strict standards, and that he adopted an orphaned girl named Adele, who was probably mentally handicapped—she was institutionalised after his death—and doted on her his entire life. In some of his morality campaigns, Comstock asked himself how far was too far, established limits on his own behaviour, and achieved reasonable success. He significantly reduced newspaper advertisements for nostrums by quack doctors, the open sale of pornography by street vendors, and the spread of gambling establishments. However, Comstock is remembered today not for the moderate amount of good that he accomplished but for his unreasonable campaign against the poorly defined concept of obscenity in literature and the state and federal legislation and prosecutions that resulted. Two years before his death, he would boast that his convictions would fill nearly 61 train cars of sixty people each, or approximately 3,700 people.

In their 1927 book, Anthony Comstock: Roundsman of the Lord, biographers Heywood Brown and Margaret Leech observe that Comstock did not have the slightest appreciation for beauty or books. He was also a poor speller. In the diary he kept while fighting for the Union in the American Civil War, in an entry dated 9 November 1864, Comstock wrote: “Spent part of day foolishly as I look back, read a Novel part through.” Other entries repeatedly betray the guilt he felt for succumbing to an unspecified sin, presumably onanistic, given that he was nineteen at enlistment.

Comstock’s tipping point from reformer to persecutor came on 2 November 1872 when he demanded that US Marshals arrest sisters Victoria C. Woodhull and Tennessee Claflin. The sisters operated a brokerage office in Manhattan’s financial district and published a reform-minded newspaper called Woodhull and Claflin’s Weekly, which often argued for equal rights for women. (Although she was too young for the office, Woodhull had been nominated by the Equal Rights Party as candidate for president of the United States in May of that year.) The Weekly’s 2 November issue contained an exposé of Reverend Henry Ward Beecher’s affair with his friend’s wife. Because she herself supported “free love,” Woodhull criticised Beecher for his hypocrisy rather than for his extramarital relations.

Comstock, who did not distinguish between slander and obscenity, considered her allegations about a minister’s infidelity slanderous and therefore obscene. He brought charges under a pre-existing federal statute, passed in 1865 and updated in June 1872, that prohibited the mailing of obscene publications. To Comstock’s chagrin, in June 1873 the case against the sisters was dismissed by a judge on the grounds that the 1872 statute did not apply to newspapers.

Incensed by his failure to convict these two feminists, who referred to him as “this illiterate puppy,” Comstock went to Washington, DC, to lobby Congress for a comprehensive bill that would close the loopholes in the 1872 law. He was assisted by his friend and sponsor, the banker Morris K. Jesup, who also helped found the American Museum of Natural History. The 1873 Comstock Act was passed as a result of this visit to DC, and Comstock also received an unpaid commission as Special Agent of the Post Office. By the end of the year, he had arrested 55 people under the new law.

At Comstock’s urging, the New York City YMCA had created a Committee on the Suppression of Vice in 1872, which was chartered by the New York State legislature as the Society for the Suppression of Vice in 1873. The left half of the Society’s seal depicted the arrest of a malefactor. The right side depicted the burning of books.

The Society, which received half the fines levied on those it successfully prosecuted, and was funded by New York City’s elite, raised US$10,000 a year for Comstock’s work. Though the Society formally separated from the YMCA in January 1874, there continued to be significant overlap between the leaders of both organisations. Financial supporters of the Society included Reverend Henry Ward Beecher’s son, the lawyer William C. Beecher; businessman and YMCA founder William E. Dodge, Jr.; Samuel Colgate; publisher Alfred Smith Barnes; and J.P. Morgan.

In the years that followed, Comstock successfully lobbied for additional state and federal legislation prohibiting the mailing of obscene content. Although genuinely obscene publications, the main object of his campaign, had been more or less eradicated by 1877, his fanaticism required a steady supply of targets. He went on to arrest and prosecute doctors and nurses who provided contraceptives and abortion, newspaper publishers like D.M. Bennett, and art gallery owners like Herman Knoedler, who displayed photographs of paintings of nudes honoured by the Paris Salon. (Ever a poor speller, Comstock raged against paintings that he thought “had been exhibited in the Saloons of Paris.”)

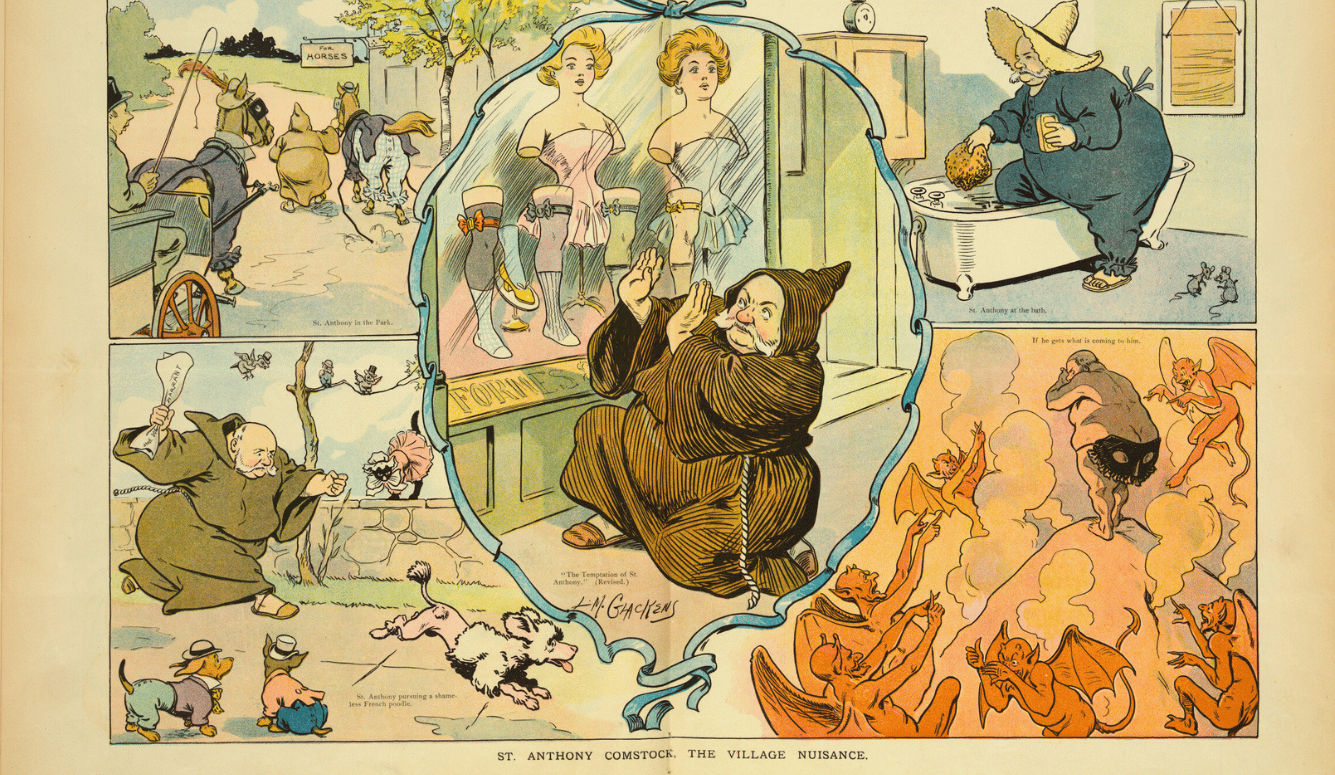

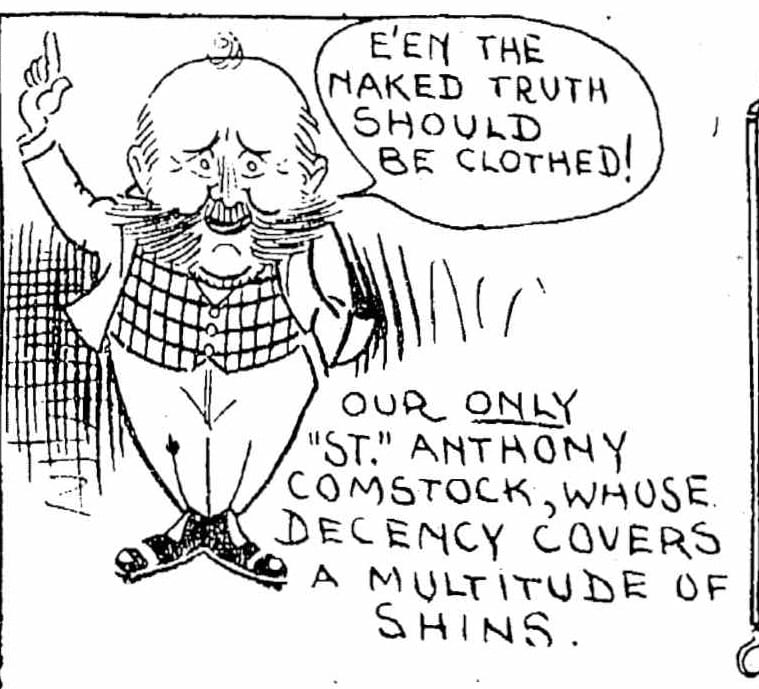

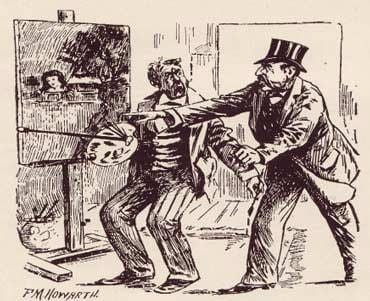

(L) Satirical cartoon mocking Anthony Comstock’s censorship crusade, insisting that even “naked truth” must be clothed. (R) Caricature of Comstock forcibly suppressing art under the Comstock Acts.

The men and women he arrested were frequently sentenced to large fines, imprisonment, and hard labour, in addition to enduring public scorn. After abortifacient seller Ann Lohman killed herself following her arrest, Comstock boasted that he had driven fifteen people to suicide by his efforts. Often more interested in appearances than substance, he tried at one point to prosecute Arnold Daly, the producer of George Bernard Shaw’s Mrs. Warren’s Profession, because the play addressed prostitution, even as prostitutes sold themselves outside the Broadway theatre. Two of three judges voted to acquit Daly, and Shaw’s play profited from the publicity.

Comstock’s crusade against literature had far-reaching effects. Because of the state and federal Comstock Acts, classics like Lysistrata, Gargantua, The Canterbury Tales, The Decameron, and The Arabian Nights could not be sent through the mail. Nor could contemporary works by Balzac, Victor Hugo, Oscar Wilde, Ernest Hemingway, John Dos Passos, Eugene O’Neill, James Joyce, John Steinbeck, William Faulkner, and F. Scott Fitzgerald. Medical textbooks with anatomical illustrations also fell afoul of the law. Parts of the federal Comstock Act were struck down in Roe v. Wade and Griswold v. Connecticut, but the Act itself still remains in force. It was cited 27 times in the main body of US District Judge Matthew J. Kacsmaryk’s 2024 ruling on FDA v. Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine, the legal challenge to mifepristone. His ruling was thrown out by the US Supreme Court later that year.

H.L. Mencken decried the sentimental, watery porridge that Comstockery had made of American literature.

In “Puritanism as a Literary Force,” an essay in his 1917 Book of Prefaces, H.L. Mencken decries the sentimental, watery porridge that Comstockery had made of US literature. Comstock, Mencken argued, was the embodiment of two twinned forces in American history: Puritanism and philistinism. Classical Puritanism, he noted, had certain merits when its accusations and examinations of conscience were turned upon the self, but the period of prosperity following the Civil War had created something entirely different: the “Puritan entrepreneur” or “professional sinhound,” who was always ready to persecute others to demonstrate his virtue instead of examining and correcting his own behaviour.

Mencken’s complaints about the American literary environment in the 1910s, the result of decades of Comstock’s persecution, could be applied with little alteration to today’s online commentariat:

A novel or a play is judged among us, not by its dignity of conception, its artistic honesty, its perfection of workmanship, but almost entirely by its orthodoxy of doctrine, its platitudinousness, its usefulness as a moral tract. ... The Puritan’s utter lack of aesthetic sense, his distrust of all romantic emotion, his unmatchable intolerance of opposition, his unbreakable belief in his own bleak and narrow views, his savage cruelty of attack, his lust for relentless and barbarous persecution—these things have put an almost unbearable burden upon the exchange of ideas in the United States.

Very little was written in that repressive period that Mencken considered worthwhile. He acknowledged that he himself, in his capacity as editor of a magazine, had turned down excellent work that would have been published in Europe, for fear of his office being raided.

In response to prosecutions by Comstock and the various Societies for the Suppression of Vice, publishers inserted morality clauses into their contracts, requiring authors to guarantee their books contained no “immorality” and to indemnify publishers if the book was targeted. The John Lane Company’s contract for Theodore Dreiser’s The Genius, signed on 30 July 1914, included the clause: “The author hereby guarantees ... that the work ... contains nothing of a scandalous, an immoral or a libelous nature.” Clauses like these made no sense, Mencken observed, because the publisher or one of its employees had presumably read the book before issuing a contract and knew its contents as well as the author did.

In 1916, after The Genius had already sold 8,000 copies, the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice threatened to prosecute John Lane Company unless the book was withdrawn from publication. Cowed, the publisher promptly did as it was told. Though Mencken did not think much of The Genius, he spent US$300 in postage, stationery, and his secretary’s time soliciting signatures for a statement of protest against the suppression of Dreiser’s novel. Many American writers declined to sign, and the behaviour of several led Mencken to remark acidly that the fear and envy of other writers were a great benefit to the Puritan “book-baiters.” The first to add their names to the protest, by telegram from London, were English and Irish: Arnold Bennett, William J. Locke, E. Temple Thurston, and H.G. Wells. In 1918, Dreiser sued his publisher for breach of contract, after a reputable lawyer volunteered to represent him, but the court dismissed the case. The Genius was re-issued by Horace Liveright in 1923 and sold 12,301 copies by the end of that year.

Anthony Comstock died in 1915, but his laws and concerns outlived him. That same year, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled in Mutual Film Corporation v. Industrial Commission of Ohio that free speech did not extend to films and that Ohio’s board of film censors could continue proscribing films and arresting those who showed them. A flood of decency laws aimed at films soon followed, prompting the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America to hire Will H. Hays to lead them over that difficult terrain. Hays recommended that Hollywood self-censor rather than leaving censorship to the states. He eventually formalised what would become known as the Hays Code, a technically voluntary set of guidelines on what could be depicted in film, which in practice was enforced by the Hays-created Production Code Administration.

While state censors and then the Hays Office regulated the content of films, morality clauses entered the film industry in a new form, controlling not the content of the film but the behaviour of the artist. During the McCarthy hearings, morality clauses were invoked against the Hollywood Ten, who were blacklisted and imprisoned for refusing to cooperate with the House Committee on Un-American Activities. In 1954, the Ninth Circuit Court held that screenwriter Ring Lardner Jr.’s refusal to disclose whether or not he was a communist breached the morality clause in his contract, which stipulated that Lardner do nothing to “offend against public decency, morality, etc.,” and that Twentieth Century Fox was therefore justified in firing him. Very few blacklisted writers, artists, and directors—a group far larger than the Hollywood Ten—ever recovered their careers.

Gay actors, including Rock Hudson and Tab Hunter, had morality clauses in their contracts held over their heads when their homosexuality was discovered. If the actor was profitable to the studio, the studio resorted to measures other than contract termination, such as an arranged marriage to a woman. These clauses are rarer in Hollywood now, thanks to the Writers Guild of America and Directors Guild of America banning morality clauses in their basic agreements, though SAG-AFTRA has not followed suit.

Today, the largest publishers—including Christian publishers, who returned to the practice sooner than the rest—issue contracts with morality clauses even stricter than Dreiser’s. Simon & Schuster’s might be the most egregious, requiring the author to repay a book’s advance in full should the author be publicly accused of either violating a law or of “any other conduct that subjects, or could be reasonably anticipated to subject the Author or Publisher to ridicule, contempt, scorn, hatred, or censure by the general public or which is likely to materially diminish the sales of the Work,” a decision to be made at “Publisher’s sole discretion.” Under those conditions, the book would be withdrawn as well. Notably, no evidence or substantiation of those accusations is required. The clause was invoked in 2020, when Simon & Schuster dropped Josh Hawley’s book after the 6 January riots. Regnery, which also has a morality clause in its contract, would later publish it instead.

The trouble with these developments is that by transferring all legal, reputational, and financial risk from publisher to author, morality clauses in book contracts place extraordinary pressure on authors to conform to the political orthodoxies of the day. And even then, conformity may not suffice. If any modern moral entrepreneur wishes to harm an author, especially a Simon & Schuster author, any accusation of misbehaviour—even a false one—will do. The power to suppress books has been handed to would-be Comstocks, or as Mencken called them, “professional sinhounds” and “book-baiters.” To get a book published in the present era, a canny author will likely agree upon every point with one mob or another, however dishonestly, to receive its temporary protection and avoid its wrath, while hoping and praying that no envious rival will launch a baseless attack, as happens frequently (but not exclusively) in the realm of Young Adult fiction.

In her 2017 book Kill All Normies, Angela Nagle observes that the appearance of virtue is the currency of the online Left, that its value as a currency depends on its scarcity, and that it is possible to increase the value of one’s own holdings by denouncing other leftists and liberals, thereby removing virtue from the marketplace. Writers who spend too much of their time online are often swept up in this dynamic, which has nothing to do with craft, with the act of writing, or with literature. Since the time of Apelles and Antiphilus, artists have known that it is easier to falsely accuse another writer or artist than to write a good book or paint a masterpiece.

As Mencken pointed out over a century ago, the threat implicit in morality clauses and the environment of fear produced by Comstock-style persecution do not encourage the creation of good literature. The best authors and artists are nonconformist by nature and individual in their opinions by necessity. For publishers to hold books hostage to the whims of mobs is an abrogation of the responsibility of publishing, which is not censorship of nonconformists but the advancement and deepening of culture and human understanding. Both the Authors Guild in the US and the Society of Authors in the UK publicly oppose morality clauses, although the Society of Authors, somewhat inconsistently, does not oppose the Scottish Book Trust’s version of a morality clause.

The century-old moral panics and persecutions by Anthony Comstock and the Society for the Suppression of Vice are echoed today by the ACLU’s new determination to censor books, the YMCA’s 21st-century persecution of women and girls, and publishers’ frequent spasms of terror and recourse to morality clauses, among other fear-driven behaviours detailed by SEEN in Publishing’s “Everyday Cancellation in Publishing” report. What’s novel about today is how both Left and Right are deploying moral panics for their own ends. Extremists on both sides have sought to suppress and censor literature, from libraries removing Dr. Seuss books and publishers bowdlerising Ursula K. Le Guin to police officers being called on school librarians and the Trump administration attempting to shutter the IMLS. In 1887, Anthony Comstock wrote: “Art is not above morals. Morals stand first.” On that point, booksellers refusing to carry Harry Potter and Moms For Liberty would both agree.

Artists, however, tend to think otherwise.

I am hardly a detached observer. I signed a modified morality clause in my publishing contract for Break, Blow, Burn, and Make and in 2024 was assailed by a mob in a moral panic. That mob was instigated by an unsuccessful male writer who mistook Boston for Paris, just as Comstock mistook “Paris Salon” for “Paris Saloon.” As is standard in such cases, the bien pensants in literature, including most of my friends, have decided that writing truthfully is a far worse crime than death threats, slurs, the arrest of comedians for decrying unlawful conduct, or multiple governments locking women up with convicted male rapists. Those in theatre who have campaigned to silence and suppress actress and dialect coach Mary MacDonald-Lewis on the same pretexts have been more effective than Comstock could ever have hoped to be.

The answer to Comstock, the answer to McCarthy, and the answer to their modern-day descendants is the same as it always is: courage, discernment, and laughter. The writer should speak and write fearlessly in spite of morality clauses; agents should strike those clauses out of contracts; the publisher should neither bow to the mob nor force the writer to bow to it; and each individual should bear the responsibility of being an individual and stand apart from the howling mob. Laugh as well, Doris Lessing advises in Prisons We Choose to Live Inside, because laughter is a heretical act. Naked emperors waddling about are, after all, absurd, and so is our determination to repeat the 1910s. These tasks are as hard as they ever were, but we are not spared by our failure to carry them out.