Holocaust

The Destruction and the Resurrection

An interview with the curators of the Ghetto Fighters’ Museum, the first Holocaust museum founded by Holocaust survivors.

“Nothing can replace the live testimonies of survivors who smelled, witnessed, and felt on their skin the inhumanity of the Holocaust, but eighty years on, very few survivors remain,” says Anat Bratman Elhalel, chief archivist and director of Archives at Israel’s Ghetto Fighters’ Museum. “We are now at a pivotal junction in history as we shift from personal to collective memory,” when the burden of keeping the Holocaust memory alive will fall fully on museums, archives, and dry encyclopaedias.

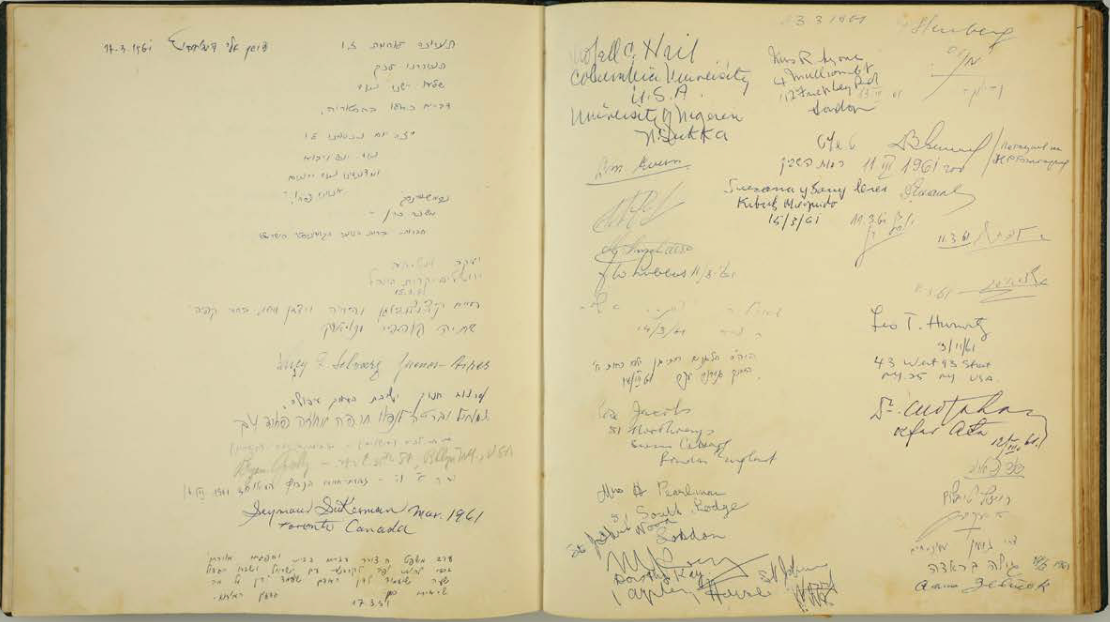

“This poses a challenge that we have been addressing for quite some time,” adds the museum’s chief curator, Liat Margalit. “Our exhibition Past Continuous addresses this burning question with telling, loaded records from our vast archive—sixteen artefacts from the past that evoke reflections on the present day, as well as the shape of things to come.” Among these are a roll of film smuggled to London during the war; a long list of Jewish deportees from the Westerbork transit camp; Yitzhak Katznelson’s haunting poem Song of the Murdered Jewish People; a 1961 entry in the museum’s visitor book made by Adolf Eichmann’s prosecutor, Gideon Hausner, on the eve of the landmark trial; encouragement cards from Janusz Korczak’s orphanage; and a child’s pair of shoes found in Treblinka. “Each artefact,” Margalit tells me, “is a story in itself, opening the door to humanity’s darkest hour, but also carrying vivid links to the present.”

Selected from the museum’s archive of 2.5 million records, Past Continuous spans the full gamut of the Jewish people’s World War 2 experience—from pre-war youth movements and hunger-ridden ghettos to the reality of the extermination camps, followed by rebirth and resurrection in the Jewish state.

“Our visionary founders were leaders of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising, partisans and holocaust survivors,” explains Bratman Elhalel. “They carried many of the items in their suitcases and bags as they journeyed from ruined Europe to mandatory Palestine. They had a profound understanding of the power of an archive to bear witness and serve as evidence when all survivors perish. In 1949, in Israel, they put out a message asking people to bring any Jewish items connected not only to the Holocaust but also to the life of the Jewish people before the Nazis came to power. We are continuing their work, honouring their legacy and preserving the dignity of millions of innocent souls.”

Here, archivist Anat Bratman Elhalel and curator Liat Margalit reflect on the last remaining Holocaust survivors still with us, why education is key to fighting antisemitism, exposing racism, and keeping the memory of the victims alive, why survivors’ children and grandchildren are themselves part of the Holocaust story, why the Holocaust is a unique event in human history, and how the museum’s singularly powerful archive helps shape the current cultural discourse.

Hannah Gal (HG): Founded in 1949, the Ghetto Fighters’ Museum is the first Holocaust museum in the world founded by Holocaust survivors. Why is this place so significant?

Anat Bratman Elhalel (ABE): It is unique because of its archive, which started in essence in Europe with the treasured items carried by survivors in their suitcases and bags. They saw the museum as continuing the archival work that started secretly in the Jewish ghettos. They believed that, although they were living freely in a new, democratic state, they had to collect the evidence that could one day be used to bring the Nazi perpetrators and their collaborators to trial. They had an uncompromising obligation to commemorate their loved ones, families, communities, and the Jewish people as a whole. It was a life mission for them—they were young people living in tents in the kibbutz they had just founded, and the very first building they designated was for the archive, library, and the first exhibition.

Liat Margalit (LM): This museum is unique because of the legacy that was put down by its founders. Some were leaders of the historic Warsaw ghetto uprising, some were partisans and youth movement leaders, but most significantly, they were educators in their DNA. Their vision was a place that will not just be a memorial for those who perished but a centre of education about the human spirit, where people can learn about justice, morality, and personal responsibility.

HG: Past Continuous features a March 1961 entry in the visitors’ book made by Gideon Hausner, the legendary prosecutor at the Eichmann trial. It reads, “On the eve of the evil man’s trial, I went to Ghetto Fighters Museum and breathed in its atmosphere so I can be a mouthpiece to the victims.” These striking words were part of his iconic opening speech.

ABE: Before him was the mammoth task of speaking on behalf of the six million victims and he sought reassurance. In his trial opening speech he said, “Their blood screams but their voices cannot be heard.”

Yesterday, I got Hausner’s book out of our library to reread the paragraph referring to his 1961 visit to our museum. He writes, “At times I would be tormented by doubts regarding my ability to present before the court events so far removed from my own personal experience. I did not personally experience the horrors of the Nazis. Sometime before the trial, I decided to visit the kibbutz. I spoke with Zvia Lubetkin and with her husband, who were among the leaders of the legendary Warsaw uprising. For hours I listened to this remarkable couple, who embodied in their very being both the destruction and the resurrection. ‘Wasn’t setting the date for the general uprising one of the most difficult decisions?,’ I asked. ‘Yes,’ they replied. ‘We knew that once we began an open mass action, it would mean the end for every person in the ghetto.’”