Genetics

Bodies of Evidence

When combined thoughtfully with traditional historical methods, analysis of ancient DNA can illuminate the lives, characters, and motivations of people long dead.

Hitler left blood. Richard III left bones. Lenin left an entire body, preserved like a specimen.

For centuries, historians and biographers have understood the powerful by scrutinising their words and letters, dissecting their decisions, and weighing the testimony of those they governed. But the recent rise of ancient DNA research has opened unsettling possibilities for analysing the actions of our rulers both past and present on the basis of their biology. This new perspective complicates but does not replace traditional interpretation; it could challenge old assumptions or further reinforce them. More significantly, however, genetics offers a tantalising—and possibly distorting—shortcut to understanding the minds that have shaped, or are now shaping, our world.

Ancient DNA (aDNA) analysis has moved far beyond tracing human ancestry and patterns of migration. Over the last decade, it has become a tool for detailed personal reconstruction, revealing previously impossible information about past individuals, including their health, diet, relationships, and physical appearance. And aDNA can now increasingly provide clues—sometimes surprising ones—not just about the bodies of the long-dead, but also about traits linked to neurological or behavioural tendencies.

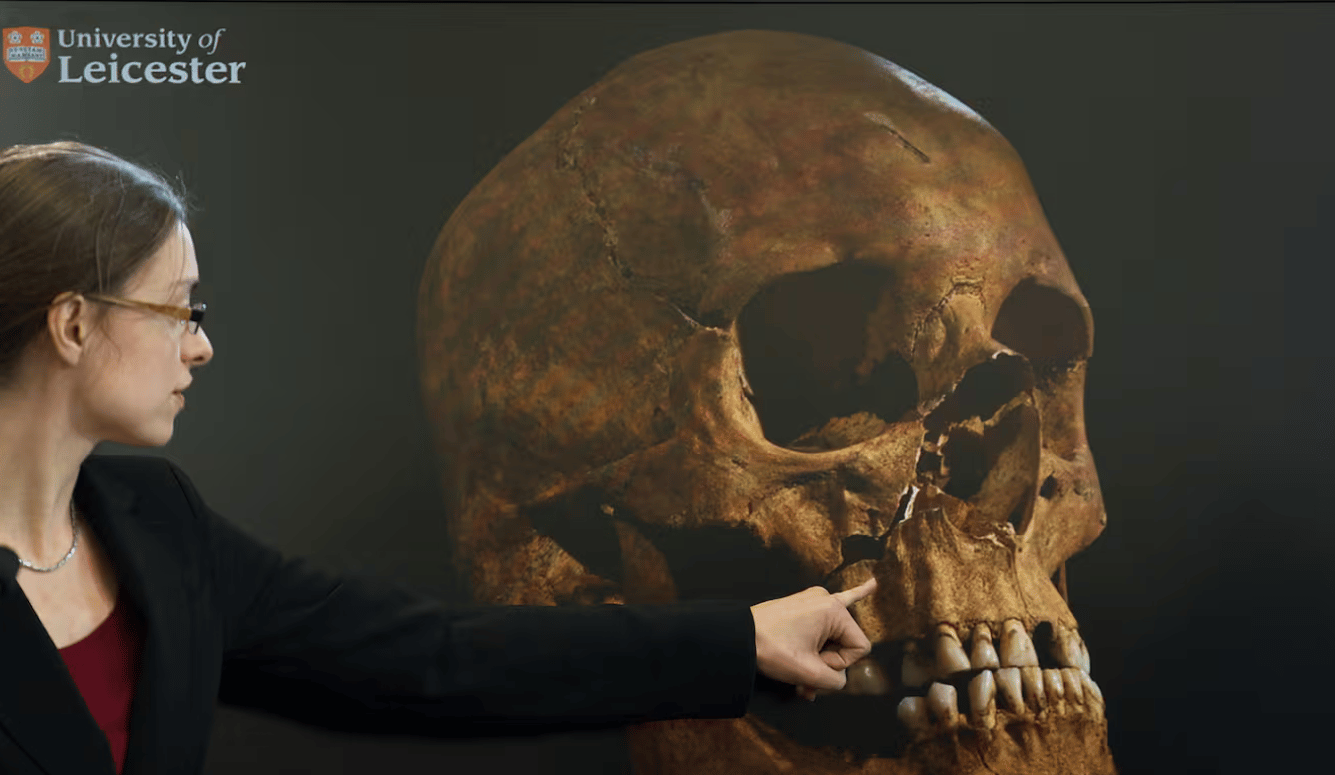

One of the first cases to fully capture the public imagination involved human remains unearthed beneath a car park in Leicester, England, in 2012. Standard forensic examination revealed that the individual had suffered “multiple blows to the head,” including a “massive, fatal blow to the base of the skull.” The historical and archaeological context suggested that the skeleton could be that of Richard III, England’s last Plantagenet king, deposed by Henry Tudor at the Battle of Bosworth in 1485. Radiocarbon dating further strengthened this possibility—yet only aDNA analysis could conclusively confirm it.

And the aDNA also revealed further intriguing details. It indicated that Richard likely had blond hair and blue eyes—details at odds with the dark-visaged villain of Tudor propaganda depicted in Shakespeare’s eponymous play as a “deformed, unfinish’d” hunchback (although severe scoliosis had indeed caused curvature of the king’s spine). Such findings demonstrate how genetics can undercut centuries-old caricatures—and also hint at deeper possibilities. Shakespeare’s play has been described as “an intense exploration of the psychology of evil, centered on Richard’s mind.” Modern genetic techniques could potentially probe for the markers of such ‘evil’—or at least those genetic variants associated with sociopathic tendencies. Although such markers are probabilistic and still scientifically contentious, their presence or absence could add a critical new dimension to Richard’s long-standing reputation, shifting the focus further towards or away from personal pathology or historical bias. Integrating genetic insights with traditional analysis, therefore, promises a richer, more nuanced understanding of the man and the myth of this long-despised king.

The recent identification and analysis of Adolf Hitler’s DNA marks one of the most troubling yet illuminating applications of modern genetic science. Long thought irretrievable—his body having been burned in 1945 on his own orders—the Nazi dictator’s genetic profile was reconstructed from a bloodstain preserved on a fragment of his (literal) deathbed, the sofa on which he killed himself. Once a DNA match with an Austrian male-line relative had been confirmed, researchers were able to calculate polygenic scores—statistical estimates of genetic predisposition to various conditions. Some of the results quickly became clickbait headlines. A deletion in the PROK2 gene, for example, associated with Kallmann syndrome, lends plausibility to the old rumour that the Führer had an undescended testicle—or, as the British wartime song put it, that “Hitler has only got one ball” (though it is doubtful that “the other is in the Albert Hall”). At the same time, the study helped refute another persistent rumour, that Hitler had Jewish ancestry on his father’s side; the genetic analysis shows this is unfounded.

What, though, does the DNA suggest about the psychology of one of history’s most reviled figures? The findings certainly indicate an elevated genetic propensity for ADHD and autism and place his score for antisocial traits—a proxy for psychopathy—within the top ten percent of the population. Yet as the researchers are at pains to point out, these are probabilities, not diagnoses; they do not capture the environmental influences on Hitler’s psyche, which included the trauma of losing four siblings and both parents before he turned eighteen. DNA does not determine destiny, and Hitler’s genetic profile in no way implies that he was somehow “born” to turn into the monster he became. Instead, it adds another layer—disturbing, fascinating yet incomplete—to the portrait already drawn by history.

If Hitler’s genome represents the latest (if grimmest) triumph of aDNA analysis, Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov—better known to history as Lenin—presents almost the opposite case: a body fully preserved yet genetically unread. Lenin’s corpse was meticulously embalmed after his death in 1924, both as an act of Bolshevik reverence designed to “freeze his ideals in time” and as a theatrical display of Soviet scientific prowess (conceivably with the intention of one day bringing him back to life). The body remains on public display in a purpose-built mausoleum in Moscow’s Red Square and is still maintained by a dedicated scientific team, who administer weekly bleach treatments to prevent fungus and mould. Despite a century of near-religious attention, however, mystery still surrounds Lenin’s fatal illness. What killed this relatively fit, teetotal 53-year-old? The official cause of death was severe atherosclerosis or hardening of the arteries, which would be consistent with the nausea, seizures, and partial paralysis that afflicted him before his death. Yet there have long been suspicions that Lenin succumbed instead to sexually transmitted neurosyphilis, a late-stage complication of syphilis that attacks the brain and nervous system and presents with similar symptoms.