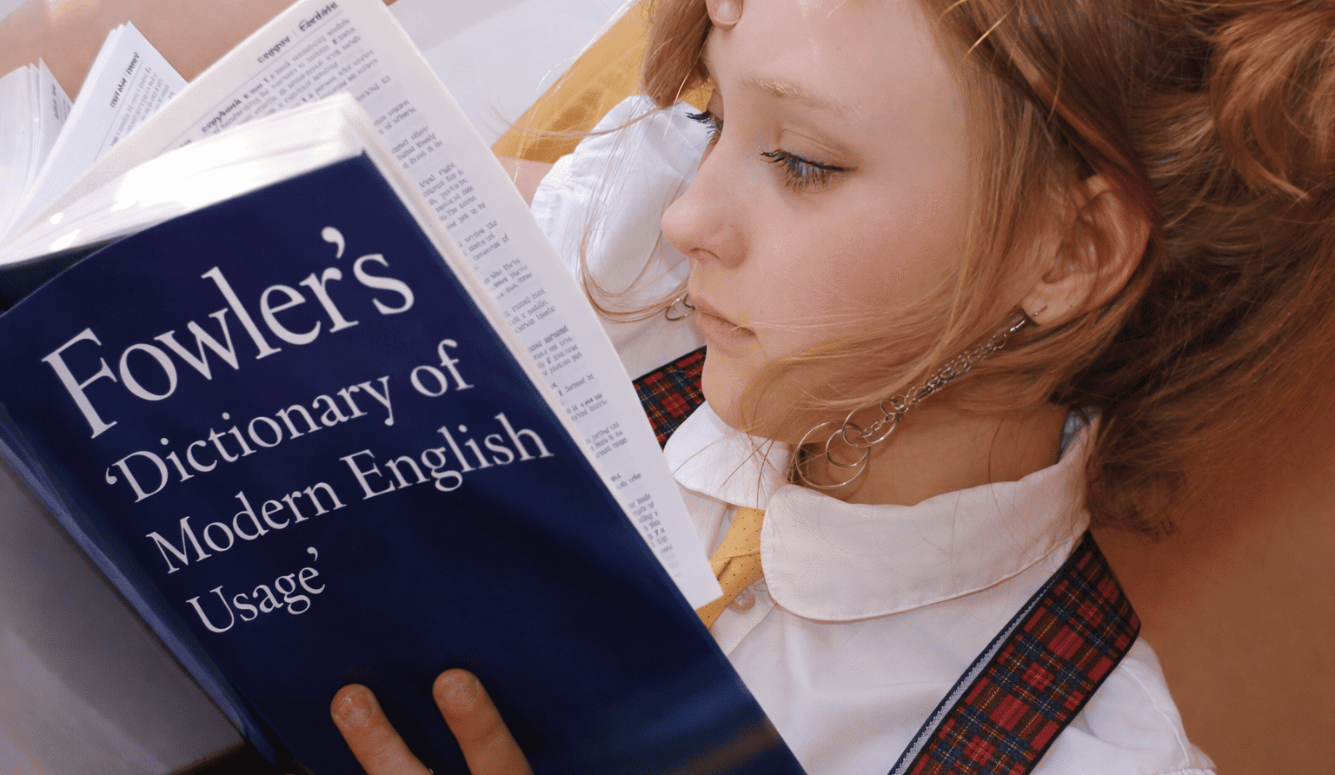

The grammarian H.W. Fowler is worthy of commemoration. His Dictionary of Modern English Usage, the centenary of whose publication falls this year, has had an outsized cultural impact in the English-speaking world. Its edicts live on in the style guides of many newspapers, including the New York Times. Unfortunately Bruce Gilley’s celebration of Fowler in these pages goes well beyond the evidence, and sometimes in perplexing ways.

Gilley misunderstands basic aspects of English grammar and misrepresents the approach of scholarly linguists to Fowler’s enterprise. Further, he invokes the authority of Fowler to urge “the importance of gatekeeping” and arresting “cultural decay … by holding the linguistic vandals at bay.” This aim is quixotic, misguided and corrosive. And it’s not the type of philosophy I’d expect to find in Quillette, which stands for science, critical inquiry, and—in the broadest sense—liberalism.

Let’s start with a point of agreement. There’s much to admire in Fowler. He was a stylish writer who knew a lot about grammar, as did his reviser Sir Ernest Gowers. As a journalist, I’ve sometimes found it useful to cite Fowler’s sensible defence of split infinitives and other purported grammatical errors. But his linguistic judgments were often otherwise eccentric. Amazingly, Gilley expounds (inaccurately) and extols possibly the single most perverse of all Fowler’s idées fixes, the so-called “possessive with gerunds” rule.

Fowler’s own example of the purported solecism he seeks to correct is: “Women having the vote reduces men’s political power.” He claims this type of construction is “grammatically indefensible.” Why? In Gilley’s telling, it’s because it involves “using the participle ‘having’ as a noun (a verbal noun or gerund) without modifying ‘women’ to its adjectival form ‘women’s’.” Hence it is mandatory (not merely optional) to write instead “women’s having the vote…”

Your eyes may glaze over if I explain why this grammatical reasoning fails, but you’re still owed an explanation, as is Gilley, so I’ve put it in a technical note at the end. It’s not necessary to read that addendum in order to follow my argument here. It’s enough to say that Fowler is trying to replicate a distinction that exists in Latin between a present participle and a gerund. That grammatical distinction doesn’t exist in English: we have lots of words ending in -ing that can be used in various ways. And it really doesn’t matter, when using this type of construction known as a gerund-participial clause, if you mark the subject for genitive case (“women’s having…”) or plain case (“women having…”).

So you can forget about Fowler’s rule—or rather, you could if only there weren’t so many style gurus, language mavens, and usage guides that weirdly insist on it. All I can say is: if you follow the “possessive with gerunds” rule consistently, you’ll end up writing laughably bad English. On Fowler’s own account (I’m not making up deliberately absurd examples in order to discredit him) you ought to be writing things like “will result in many’s having to go into lodgings” or “to deny the possibility of anything’s happening.”

No one writes like this, including Gilley. And the reason is not some shift in the language since Fowler wrote. Even at the time, scholars of language patiently dismantled this superstition. As the Dutch linguist Etsko Kruisinga wrote in 1932:

The reason why some writers insist on this construction, which is contrary to the character of modern English sentence-structure, seems to be that they have been taught this character of the -ing by teachers who take Latin syntax as the general standard to which human speech must be made to conform. The result is extremely artificial, occasionally misleading, and ludicrous English.

You can say that again. Yet, for Gilley, ignoring Fowler’s arbitrary and ill-informed stipulation is “a grievous sin against English usage.”

I wish Gilley’s claim were merely a misguided piece of mock-indignant pedantry. I’ve so far avoided mentioning the standout feature of Fowler’s scolding: as you can infer from his example, he thinks the issue of universal women’s suffrage, then not yet obtained in Britain, is a bit of a giggle. Apparently Gilley thinks so too, judging by his facetious remark that the objection to “women having the vote” is offensive on linguistic prior to moral grounds.

I’m an affable sort of chap, but in a world where women are widely subjugated and in some countries have few or no political rights—Afghanistan, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia—I’m disinclined to laugh along with Gilley. Though he cites an excellent article about Fowler in the New Yorker last year by Ben Yagoda, he appears not to have noticed, or been moved by, Yagoda’s reference to Fowler’s Edwardian misogyny.

On the contrary, Gilley shares Fowler’s belief that inescapably gendered language, such as the use of “he/him/his” as a supposedly epicene pronoun (“when the interval was over, everyone returned to his seat”), may legitimately denote both sexes. I can scarcely credit that, a century since Fowler, a writer in Quillette genuinely believes it’s vital to retain the noun phrase “linesman” rather than “linesperson” in competitive sport.

What linguistic purpose is served by insisting, contrary to English usage over centuries and to sense, that “they” can only refer to a plural antecedent and never to a syntactically singular non-referential one (“everyone enjoyed their meal”)? In what world does the adoption of non-gendered terms like “firefighter” or “salesperson” instead of fireman or salesman threaten civilisation? The notion is ludicrous.

Gilley’s warnings about threats to correct English continue in his depiction of the third edition of Fowler, edited by Robert Burchfield and published in 1996, as the product of some woke conspiracy. The volume is certainly flawed but not for that reason. Burchfield was a lexicographer whose technical knowledge of grammar wasn’t really up to the task. He makes mistakes. But the aim of deriving guidance from the usage of native speakers, rather than sitting in judgment on their supposed barbarisms, is one that every working linguist would share. It’s what motivated Samuel Johnson in compiling his pioneering Dictionary of the English Language in 1755, which is replete with numerous quotations from contemporary authors.

People do look for guidance on their use of language, and there is nothing wrong in principle with prescriptivism, provided it adheres to two principles. First, advice must be based on the facts of language rather than on personal stylistic caprices. And second, non-Standard varieties of English are precisely that: they’re not substandard or debased forms. Standard English is itself just a dialect, albeit one with social cachet: that’s the reason children (and adults) need to be fluent in it to make their way in the world, and not because it’s somehow purer, more expressive or more logical than any non-Standard form of English.

It isn’t any of these things. It’s just the dominant variety of English due to historical happenstance, and it has slightly different rules (in, for example, how it marks negation) from those of some other dialects. I’m especially concerned that Gilley derides Burchfield for describing “black English” (a highly misleading term for what’s known as African-American Vernacular English, or AAVE) as “a variety that is richly imagistic and inventive.” This is simply true, though it’s perhaps more relevant to note that AAVE has a complex grammar including detailed rules for using the copula “be” (as in “she be working”) or omitting it, known as the zero copula (“he late”). If you’re a native speaker of AAVE (I am obviously not), the salient question is not “correctness” but when to use that variety of English and when instead to speak Standard English, which is recognised by far more people and is the dialect used in the media, education, and public life.

It’s a hardy myth, heard in every generation, that civilisation is under siege from collapsing linguistic standards, and it’s always wrong. Speakers of any natural language—let alone English, which is the closest thing there has ever been to a universal language—are endlessly inventive in its use. Gilley is mistaken in positing otherwise, and his article bears the insular and remarkably convenient message that “correct English” coincides exactly with the way he himself speaks. This benighted form of snobbery has done much damage to social cohesion over generations and there are no linguistic grounds to support it. The world is a dark and divisive enough place at the moment without throwing this dogged prejudice into the maelstrom.

Technical note

Gilley writes: “The particular violation in this case, as Fowler taught, is using the participle ‘having’ as a noun (a verbal noun or gerund) without modifying ‘women’ to its adjectival form ‘women’s’.” He makes two significant errors in this sentence. First, he’s confusing lexical category (noun, verb, adjective and so on, known by traditional grammarians as parts of speech) with grammatical function (subject, direct object, adjunct and so on). Something either is a noun or it isn’t: its use is something else, a relational concept that depends on the other constituents of the phrase, clause, or sentence.

Here’s an example: “Medicine” is a noun, and in the clause “the medicine tastes disgusting,” the noun phrase “the medicine” functions as the grammatical subject. In the clause “the medicine cabinet is open,” it’s still a noun but its function is different: it’s modifying another noun, “cabinet” (in technical language, it’s functioning as pre-head modifier in the noun phrase “the medicine cabinet”).

This is relevant to Gilley’s second mistake (in which he repeats Fowler, but it’s still a mistake): “women’s” is not an adjectival form. It’s a straightforward genitive noun phrase.

It may seem finicky to pick up Gilley on these points but I think it’s justified. I’ve encountered many people in the worlds of letters, journalism, and academia—some of whom have written books on the theme—who loudly defend “correct English” while being noticeably hazy on the nuts and bolts of the language. I’ve long believed, and have written my own book arguing this case, that it would be better to improve the general level of grammatical education than lament the way native English speakers use their own language.