Anthropology

Among Savage Tribes

Napoleon Chagnon documented a society in which violent men enjoyed greater reproductive and marital success. Some of his academic colleagues never forgave him for it.

Editor’s note: Few scientific fields test the boundaries of acceptable thought as persistently as evolutionary biology. By its nature, it confronts uncomfortable questions about sex, violence, hierarchy, cooperation, and human difference.

This is the third in a three-part series, Darwinian Heresies, examining the work of prominent evolutionary biologists who provoked not only criticism but sustained institutional hostility. This series was originally published in Le Point by Peggy Sastre and has been translated from the original French by Iona Italia.

“Do you know what they’ve done to me, even though I’m a leading figure in my field? You’re in France and you want to study sociobiology or behavioural biology? You haven’t even been born yet and you’re already dead. Get out of academic life as fast as you can.”

Napoleon Chagnon wrote those words to me about twenty years ago. I was a student who’d recently become a science journalist, and I was so fascinated by his work that I envisioned pursuing a career that combined anthropology and biology, just like his. I’d written to ask him for help with a bibliography—and also to ask, “How can I become you?” Alongside the references he’d provided, he’d added this comment, like a lifebuoy made of lead. It wasn’t until fifteen years later, when I read historian of science Alice Dreger’s account and realised the full extent of the witch hunt mounted against him, that I finally understood what he’d been trying to tell me.

At first glance, Napoleon Chagnon didn’t seem to have the makings of someone who would become a household name in science. But, as his granddaughter, cinematographer Caitlin Mack, told me, his story makes far more sense when you see it as a tale of a precocious child who came from nothing and had a unique talent for making people jealous.

Born in 1938 in Port Austin, Michigan, into a poverty-stricken Canadian family of twelve children—he was called Napoleon after his grandfather and had a brother who was christened Verdun, further evidence of the family’s Francophilia—Chagnon was able to attend university thanks to his father’s meagre GI pension and to the string of odd jobs he accumulated from adolescence onwards: ambulance driver, land surveyor, labourer, delivery man... His only ambition was to provide for a future wife and children, so he embarked on a degree in physics and engineering. But the few weekly hours humanities in his curriculum changed everything. He fell in love with anthropology—as he details in his autobiography, Noble Savages: My Life Among Two Dangerous Tribes—the Yanomamö and the Anthropologists (Simon & Schuster, 2013).

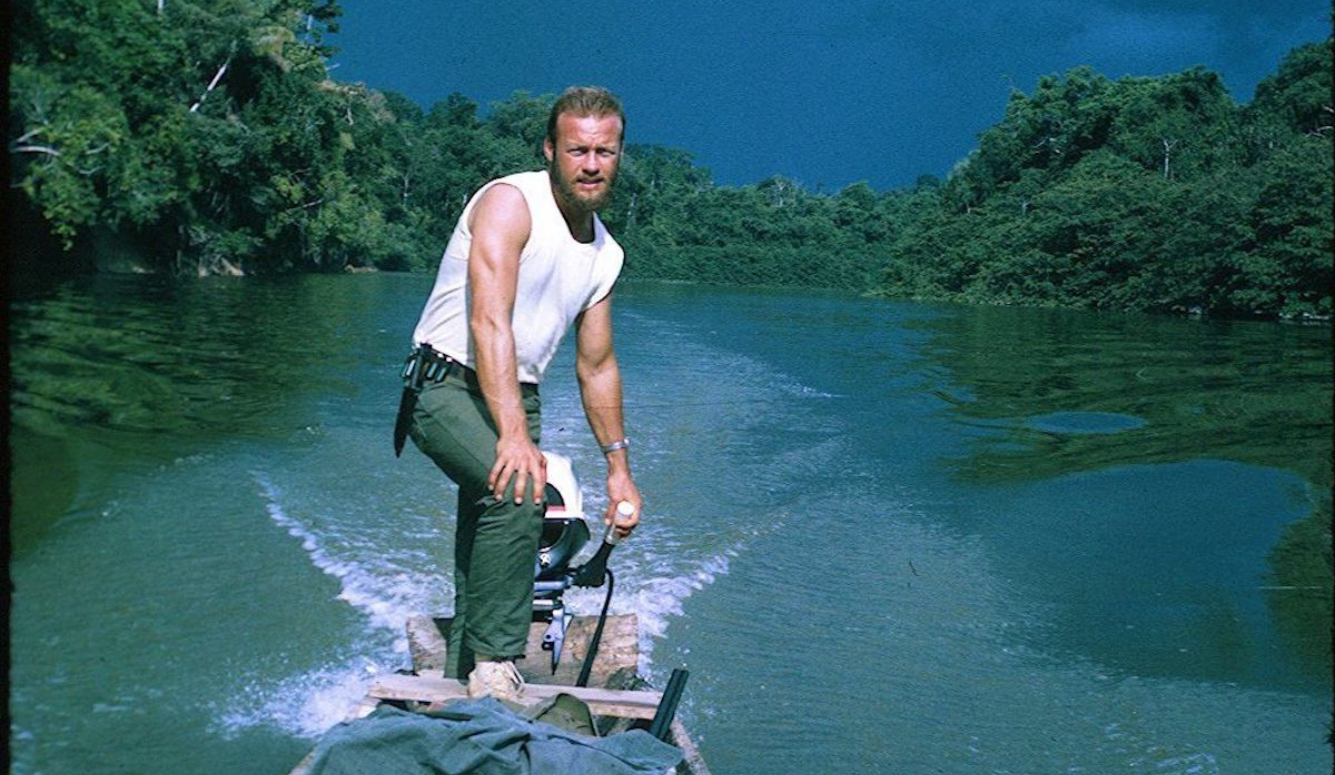

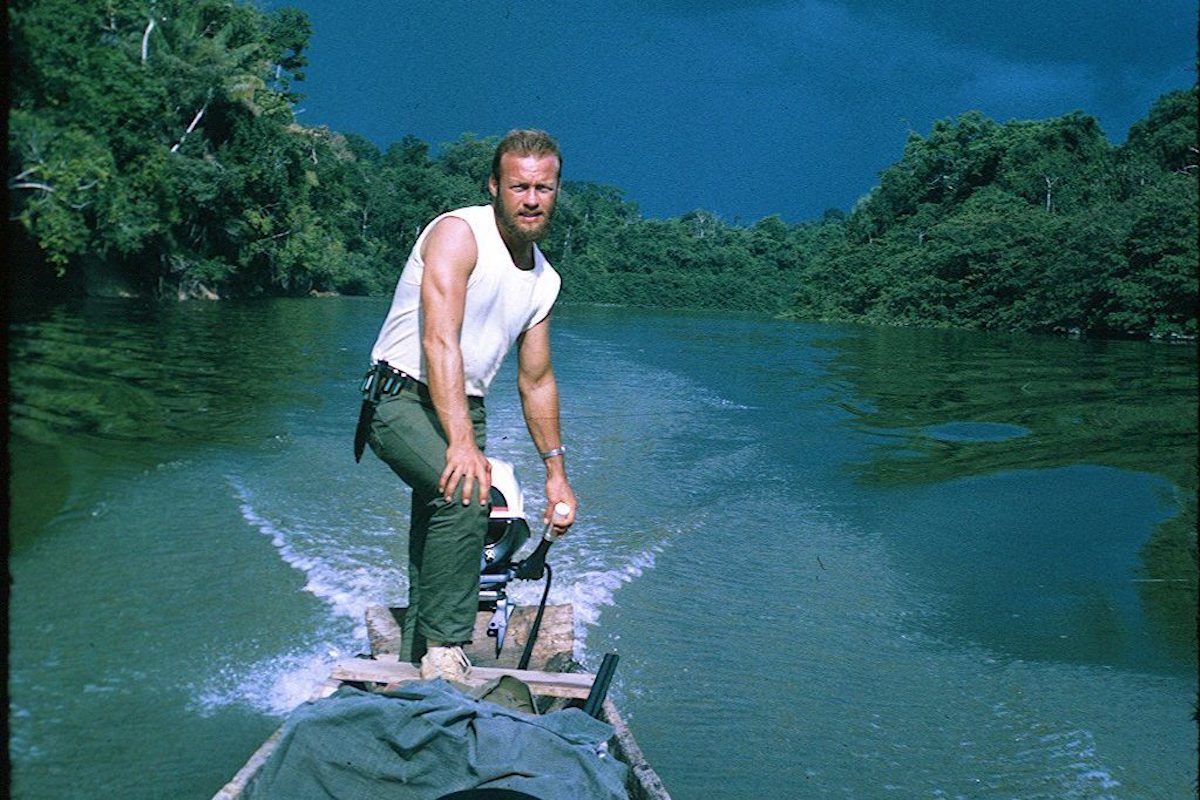

In 1964, while still a doctoral student, Chagnon set out on his first expedition to visit the Yanomamö, a tribe living in the Amazon rainforest, on the border between Venezuela and Brazil. Far from behaving like a mere anthropological tourist, Chagnon settled in, learned the language, and lived with and like them. He was to return to them every year, until this “fierce people” from the legendary Orinoco basin became his adoptive family. He was to undertake nearly thirty expeditions over the course of the following three decades, thus providing a rare window onto a primitive way of life that was tens of thousands of years old.

By 1965, Chagnon had already been awarded tenure by the University of Michigan, allowing him to dedicate himself to creating one of the most extensive and meticulous collections of ethnographic records of the twentieth century. In the field, he worked in spartan conditions—sometimes on the brink of starvation—studying the Yanomamö rigorously, methodically, and with an obsessive thoroughness. He mapped their lineages, established their genealogies and tracked conflicts, celebrations, alliances, and deaths. And while his colleagues favoured “narratives” and “qualitative” approaches, he was one of the first to bring in computers to sort, process, and structure his database.

He discovered that Yanomamö society was neither peaceful nor cooperative but held together by bloodshed and terror. Raids of rival villages were common, as was the killing of newborn babies. Women were exchanged, abducted, raped. The headmen were always, or almost always, killers, employing a brutality that wasn’t merely casual—it was systemic. With hard data to back him up, Chagnon showed that the most bloodthirsty warriors—the unokais—tended to have more wives and more offspring. In other words, among the Yanomamö, violence was rewarded with increased opportunities for reproduction. And since the strategy paid, it was widely copied.

On its publication in 1968, Chagnon’s monograph Yanomamö: The Fierce People was an immediate international success. It was translated into fifteen languages (though not into French), used in hundreds of anthropology departments, and sold millions of copies. It’s still one of the bestselling works of the discipline. Chagnon became a media darling and remained a leading authority in his field for over twenty years. But for some of his colleagues, his success was tantamount to a declaration of war. Behind the scenes, Chagnon had been making enemies. The early objections were theoretical: The dominant strand of anthropology at the time was inspired by Rousseau and Marx: “savages” were noble; violence was a by-product of colonisation or poverty. To claim that men fought over women rather than over resources and that this behaviour might even be rooted in biology was more than a provocation—it was heresy. To make matters worse, Chagnon could be arrogant—and not just about scientific matters. The man was a force of nature, a real iconoclast. Sarah Blaffer Hrdy describes her “Nap” as “a warm and good-natured man with a good sense of humour, but also endowed with a personality that might be described as ‘scrappy,’ even bellicose. He liked to provoke people.”

One of his favourite jokes concerned the difference between good and bad anthropologists: The good ones go out into the field, gather facts, construct a theory, and are ready to revise it, if necessary. The bad ones, on the other hand, cling to their theory and, faced with contradictory data, conclude they must have their numbers wrong. There was no need to spell out which side he believed he himself was on—or how he saw his detractors. And he had an even more cutting jibe, which he would trot out whenever he wanted to mock his former PhD supervisor and chief rival, Marshall Sahlins, who was convinced that parenthood in general and fatherhood in particular were purely cultural phenomena: he would remark that he was sure that the day his wife gave birth, Sahlins rushed to the maternity ward, happy to bring up any baby chosen at random from the nursery.

According to his granddaughter, Chagnon was like a little tyke who’d been knocked about a bit and was now eager to prove his worth. A working-class man with a liberal outlook, he’d been literally cut off from the world during the great cultural upheavals of the 1960s—he’d missed the “progressive” turn of the Western Left, which was already the dominant force in humanities departments full of people from far more privileged backgrounds than his. And his other mistake was believing that the rigour of his research and his devotion to the scientific method would be enough to protect him.

For a while, the war against Chagnon stayed within the normal bounds of academic controversy: people debated his methods, his “biological determinism,” his interpretations. But, from the 1980s onwards, things began to heat up and the conflict grew bitterer and more personal. Chagnon accused the Salesian missionaries, who were firmly established in the region, of political interference, distributing weapons, destabilising villages, and even spreading diseases. They never forgave him for his revelations—or for his op-eds in the New York Times, where he argued that their presence did more harm than good. By the 1990s, the various hostile parties had formed a strategic alliance. At American Anthropological Association (AAA) conferences, missionaries distributed “dossiers” of complaints against Chagnon and fraternised with his fiercest opponents. Scientific debate gradually gave way to agitprop, which was far more profitable. Chagnon was accused of peddling social Darwinism and harming indigenous peoples.

The year 2000 marked the publication of the book Darkness in El Dorado, written by Patrick Tierney, an author who described himself as “an anthropological journalist.” The book, which was accompanied by a lengthy article in the New Yorker, accused Chagnon of a horrifying litany of atrocities: triggering a measles epidemic in the Amazon by experimenting with a dangerous vaccine; refusing to treat the sick so he could observe how the virus evolved; arming rival factions in order to orchestrate conflicts; falsifying data, supporting eugenic theories, and generally behaving like a war criminal or even a genocidaire, all under the cover of academic research.

The indictment was so grotesque, so far removed from reality that it should have collapsed under its own weight. Not only were Chagnon’s research findings robust, but he had always been careful to protect the Yanomamö—for instance, by concealing his data on infanticide, fearing that the Venezuelan government would use it as a pretext to expropriate indigenous people. Right up to his death, he remained haunted by a massacre of Yanomamö carried out by gold prospectors and by his inability to secure justice for the victims when he served on a presidential commission that was swiftly disbanded in 1993. But by now, the stage had been set, and, as always with witch hunts, the bigger the lie, the more readily it was believed. Two prominent American anthropologists, Terence Turner and Leslie Sponsel—long-standing opponents of Chagnon’s—were quick to amplify the accusations. Before Tierney’s book even came out, they had already sent the AAA a letter comparing Chagnon to Mengele. When this letter was leaked to the press, the media had a field day, and—instead of defending one of its most distinguished members—the institution panicked and launched an investigation.

Everything in Darkness in El Dorado was either false or seriously misleading. The vaccine Chagnon had used was compliant with WHO protocols. The measles epidemic had started before Chagnon arrived in the field. Venezuelan doctors, the Rockefeller Foundation, the University of Michigan, the US Department of Health—they all investigated the allegations and reached the same conclusion: there had been no crime, no cover-up. But it made no difference. The AAA commission held hearings, rewrote reports, redacted documents, and politicised everything. Inconvenient facts, such as the conflict of interest caused by Turner’s involvement with the Salesians, were hushed up. Since they couldn’t make any of Tierney’s accusations stick, they decided to find something else to blame Chagnon for: having “disrupted” Yanomamö life, having been too scientific, not compassionate enough.

The entire exercise was as anti-scientific as possible and it enraged many scholars, some of whom resigned from the AAA on the spot. Among them was Raymond Hames, who nonetheless recommended Sarah Blaffer Hrdy to the commission. She declined the invitation and resigned herself. More than twenty years later, she still has vivid memories of this cold-blooded character assassination. “I read the brief that was to guide the committee and realised that this was a set up, that the conclusion could not be other than ‘guilty,’” she told me. “The problem was that back in the 1960s when Nap first went out to study the Yanomamö he thought he was signing on to do scientific research. Over the course of his career, the ‘rules’ changed. This transformation can be summed up in something one of Chagnon’s critics proclaimed at the time, which I have never forgotten: ‘We don’t do science, we do good.’ All very nice, but that’s not what Chagnon had signed on for so if the committee was supposed to find out whether or not Chagnon was working to help the Yanomamö, the only honest answer would have to be ‘No. He was there to do research.’ I wanted no part of that travesty.”

Two years later, the commission issued a report that cleared Chagnon of the most serious charges, while reprimanding him for things that are ethical lapses by today’s standards but were normal at the time. Shortly beforehand, Blaffer Hrdy received a strange letter from Jane Hill, the commission’s chair: “Burn this message. The book is just a piece of sleaze, that’s all there is to it (some cosmetic language will be used in the report, but we all agree on that). But I think the AAA had to do something because I really think that the future of work by anthropologists with indigenous peoples in Latin America—with a high potential to do good—was put seriously at risk by its accusations, and silence on the part of the AAA would have been interpreted as either assent or cowardice. Whether we’re doing the right thing will have to be judged by posterity.”

Napoleon Chagnon died on 21 September 2019, at the age of 81. At the end of his autobiography, Chagnon apologises for the increasingly “depressing” tone of his writing, overwhelmed as he was by “the lingering stench” left by the “scandal [that] exploded in the national and international press.” He had just been elected to the National Academy of Sciences (NAS), an honour comparable to a Nobel Prize, but he preferred to enumerate all the things the witch hunt had prevented him from doing: “I did not travel much, did not fish much, did not hunt grouse and pheasants over my German shorthaired pointers, did not go to many concerts, did not read much fiction for pleasure, and did not spend much time with my family.”

This piece was first published in Le Point in French on 14 August 2025 and has been translated for Quillette by Iona Italia. You can find the original here.