Videos

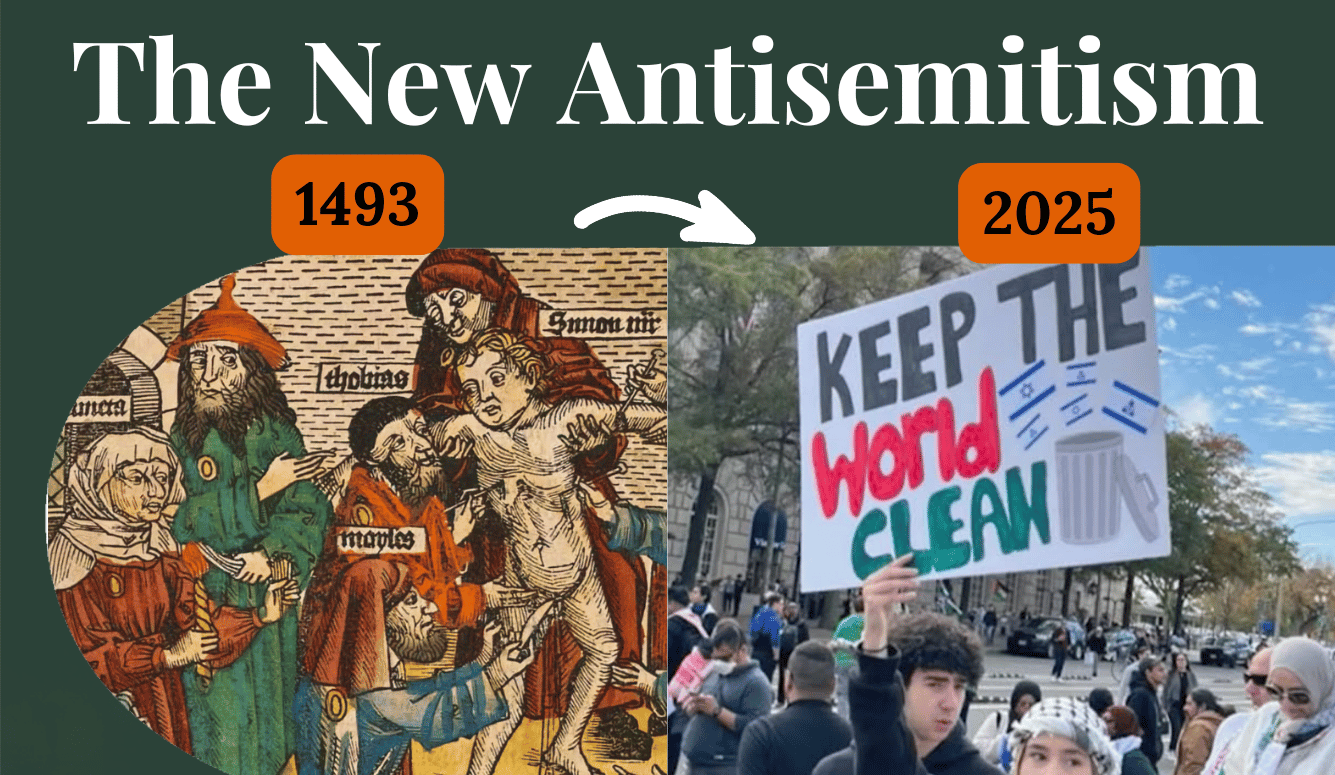

How Antisemitism Returned: From Medieval Europe to the Free Palestine Protests

Why is antisemitism resurging? Why has support for Hamas taken hold on Western campuses? And how do Qatar, media narratives, and fading Holocaust memory feed today’s crisis?

Video essay written by Benny Morris and narrated by Zoe Booth.

Introduction

For centuries, antisemitism has resurfaced in new forms—Christian, Muslim, nationalist, and now activist. This video traces the surprising continuity between medieval blood libels, 19th-century nationalism, 20th-century wars, and today’s campus protests against Israel.

The video explores how three separate forces converged:

- traditional Christian narratives of Jewish culpability

- Islamic religious hostility and historical pogroms

- modern anti-Zionism and Western cultural radicalism

We look at how antisemitic myths were transported across centuries and continents—from the Crusades and Quranic texts to Ottoman Damascus and, later, to Hamas’s modern ideology.

This video, based on a Quillette essay by Israeli historian Benny Morris, breaks down the historical, political, and cultural forces behind the return of antisemitism in the West.

Chapters

00:00 Introduction: The Return of Antisemitism

00:36 Anti-Zionism as Old Hatred Rebranded

01:17 Christian and Islamic Roots of Antisemitism

02:06 When Islam Took on Europe’s Antisemitic Tropes

03:03 Zionism, Empire and the Arab World

03:58 The West Forgets the Holocaust

04:51 Why Campus Activism Fell for Hamas

05:44 October 7 and Hamas’s Ideology

06:29 Qatar, Propaganda and the West

07:10 Jewish Communities Under Threat

07:50 Why Antisemitism Always Returns

Transcript

View full transcript

What do medieval blood libels, 20th-century nationalism, and pro-Palestine campus protests have in common? More than one might think. Antisemitism, a prejudice with roots stretching back millennia, has once again reared its head—this time cloaked in the rhetoric of anti-Zionism and resistance. But behind the keffiyehs and the placards, behind the chants of “From the river to the sea,” lies a story far older, far darker, and far more entrenched than many realise. The recent pro-Palestine protests across the West aren’t just political expressions—they’re the surface tremors of a deeper seismic shift, where Christian, Muslim, and secular forms of antisemitism have converged into something both old and newly energized. To understand how we got here, one must start in an unexpected place: a Paris museum. The Musée de Cluny, France’s medieval art treasure trove, is awash with images of Christ’s suffering—his crucifixion, his bloodied body, and his descent from the cross. It’s a visual litany that, for twenty centuries, shaped the Christian psyche. And woven into those images was a damning accusation: that “the Jews” were to blame for Christ’s death—not the Roman soldiers who executed him, not the imperial governor who ordered it, but the Jews, and their descendants, for eternity. It’s a charge that defies logic but endured nonetheless. Generations of Christians absorbed it from church pulpits, art, and scripture, often without question. The Greek composer Mikis Theodorakis once remarked that he absorbed antisemitism with his mother’s milk—a sentiment that, tragically, was not uncommon. By the 7th century, this Christian antisemitism had already made its way to the Arabian Peninsula. There, Islam’s sacred text—the Quran—cast the Jews as prophet-killers, evoking both Jesus and Muhammad. According to Islamic tradition, the Jews not only rejected Muhammad’s message but actively tried to poison him. In response, the early Islamic community engaged in brutal campaigns against Jewish tribes—killing men, enslaving women and children, and branding Jews as enemies of Islam, “sons of pigs and apes.” This theological and cultural hostility became embedded in Muslim societies. Even in places like Saudi Arabia—where Jews were absent—antisemitic sentiment flourished. Somali-born author Ayaan Hirsi Ali recalls witnessing Saudi women casually cursing Jews while hanging laundry, despite never having met one. The long arc of antisemitism bent further in the 19th century, when European nationalist ideologies imported new tropes into the Muslim world. The Ottoman Empire, decaying and vulnerable, became a conduit for these modern antisemitic myths. Events like the 1840 Damascus Affair—in which Jews were falsely accused of murdering Christians for ritual blood—show how easily old hatreds adapted to new contexts. Still, for centuries, the situation for Jews in Muslim lands remained relatively stable—as long as they remained submissive. That equilibrium shattered with the rise of Zionism. As Jewish communities in Palestine grew more assertive, Muslims across the region began seeing all Jews as potential Zionist collaborators. This fear led to deadly pogroms—in Baghdad in 1941, in Morocco, Aleppo, and Aden shortly thereafter. During World War II, support for the Axis powers in much of the Arab world was widespread. It was less about fascism and more about antisemitism and anti-imperialism. Britain and France were seen as colonial oppressors; Hitler, bizarrely, as a liberator. The defeat of Nazism and the horrors of the Holocaust temporarily drove antisemitism underground in the West. Universities that once excluded Jews began admitting them in droves. For a brief postwar moment, it seemed that Enlightenment values had prevailed. But history has a way of looping back. By the 2020s, Holocaust memory had faded, and a new convergence had begun. Muslim antisemitism, rooted in both theology and politics, met Western ignorance and fashionable anti-colonialism. The result? A resurgence of antisemitism under the guise of anti-Zionism. And thus, the streets filled. Not only with Muslims chanting “Death to the Jews,” but with Westerners who, knowingly or not, gave cover to these calls. Most young protesters couldn’t locate the Jordan River or the Mediterranean Sea—the supposed endpoints of their slogans. They knew little of the conflict’s 140-year history, of the repeated peace offers, or of Hamas’s openly genocidal charter. Instead, they knew what they saw on their screens: images of suffering in Gaza, curated to evoke maximum outrage. Missing from those broadcasts were the jihadis, the Hamas operatives who hide behind civilians and build tunnels under kindergartens. Missing too was the context—the wars, the rejected compromises, the Israeli withdrawals from Gaza and parts of the West Bank. And into this vacuum stepped Hamas. Hamas is not merely anti-Israel. Its 1988 charter is explicitly antisemitic, citing hadiths that call for the murder of Jews. It blames Jews for everything from World War I to the Russian Revolution. It promises that Islam will destroy Israel and, by implication, the Jews. The organisation hasn’t changed its core ideology, only its PR strategy—offering a watered-down version of the charter in 2017 to appease Western sympathisers. On October 7th, 2023, the ideology became reality. Massacres, rapes, hostage-taking—the atrocities were not a deviation from Hamas’s values but a fulfilment of them. And yet, the response from many in the West was not horror but justification. Blame was shifted, not to the perpetrators, but to their victims. Fueling this distortion was Qatar—a Gulf emirate with billions to spend on propaganda. Through Al Jazeera and strategic donations to Western universities, Qatar has softened the image of jihadism while simultaneously subsidising Hamas’s weapons, tunnels, and ideology. Ironically, it did so with the tacit approval of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, whose government saw Hamas as a useful foil to the Palestinian Authority and even facilitated Qatari funding. The result? A generation of activists who believe Hamas is fighting for justice, not jihad. Some of these activists are even Jewish—particularly Sephardi Jews with historical grievances against the Ashkenazi-led Israeli establishment. Figures like Oxford historian Avi Shlaim, who accuse Israel of barbarism while giving Hamas a pass, exemplify this bizarre inversion. But infighting among Jewish intellectuals is the least of the problem. Across the West, the consequences of this convergence are stark. Antisemitic violence is surging. Synagogues have been attacked. Jewish schools defaced. Jews in France and Germany are contemplating emigration—not to escape poverty or persecution in the Middle East, but to flee liberal democracies that no longer feel safe. Meanwhile, Israeli Jews, disillusioned by their government’s corruption and the endless cycle of war, are themselves considering emigration—to places like Portugal, Canada, or Germany. A grotesque irony: Jews once fled Europe for safety in Israel. Now some are looking to leave Israel for safety in Europe. The perfect storm has formed—where ignorance, ideology, and imported hatred swirl together. What began with woodcuts and Gospel blame has evolved into Twitter feeds and campus chants. But the pattern remains the same: the world’s oldest hatred finding new life in each generation. And this time, it wears a mask of liberation. This video was based on the essay “A Perfect Storm” by historian Benny Morris, published in Quillette on October 28, 2025. Morris, known for his unflinching takes on the Israeli–Arab conflict, lays bare the uncomfortable truths behind today’s protests and the history that fuels them. What’s your take? Are these demonstrations driven by justice—or by something far more sinister lurking beneath the slogans? Drop your thoughts in the comments. And if you want more fearless, thought-provoking writing like this, head over to Quillette and consider signing up. It's one of the few platforms still willing to publish what others won’t touch.

Further Reading

- Benny Morris: “A Perfect Storm” (Quillette)

- Antisemitism – Quillette Archive

- Israel – Quillette Archive

If you found this video essay useful, subscribe to the Quillette YouTube channel and browse our video archive.