Darwinian Heresies

The Unwelcome Truth about Rape

For their research showing that rape is generally motivated by sexual desire, Randy Thornhill and Craig Palmer were subjected to death threats and hounded in their personal and professional lives. And yet, they were right.

Editor’s note: Few scientific fields test the boundaries of acceptable thought as persistently as evolutionary biology. By its nature, it confronts uncomfortable questions about sex, violence, hierarchy, cooperation, and human difference.

This is the first in a three-part series, Darwinian Heresies, examining the work of prominent evolutionary biologists who provoked not only criticism but sustained institutional hostility. This series was originally published in Le Point by Peggy Sastre and has been translated from the original French by Iona Italia.

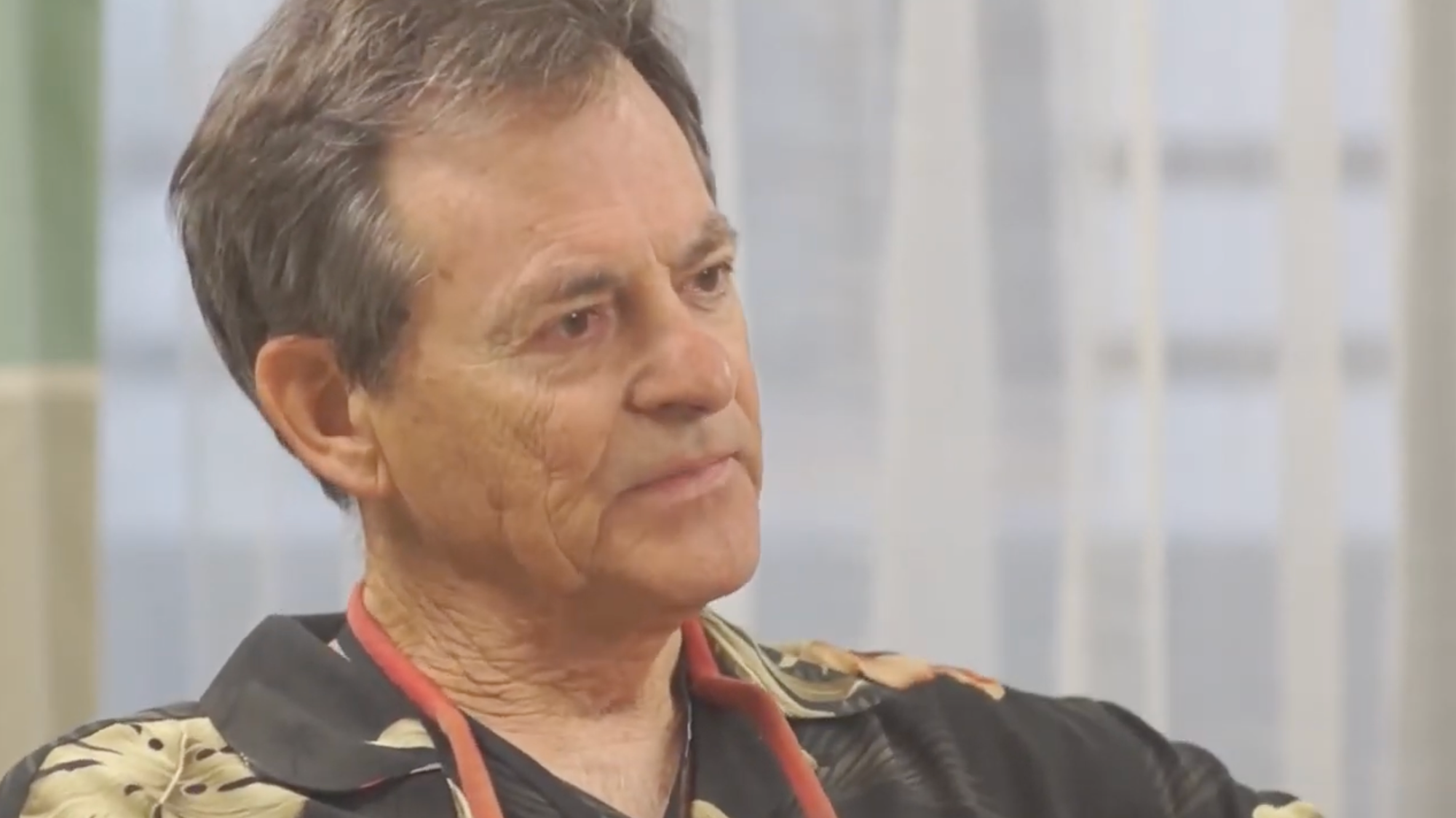

Randy Thornhill no longer answered his phone. Instead, you could hear the voice of a police sheriff, who had re-recorded the message on the biologist’s answering machine. The voice was grave. “Be warned. This call is under surveillance,” it would intone, in an attempt to deter the ill-intentioned. This was, of course, untrue, but it was intended to reduce—perhaps even stop—the death threats that had been pouring in on the scientist’s professional and home phone lines.

Some 700 kilometres away, anthropologist Craig T. Palmer generally began his days with a strange ritual: he would crouch down by his car’s exhaust pipe and inspect the chassis, looking for an explosive device. Then—also on the recommendation of law enforcement—he’d vary his route to campus, where a “secure” parking spot awaited him. This was the price the two researchers paid for the crime of demonstrating that rape is a sexual act.

What has gone down in history as “the Thornhill and Palmer affair” was an academic witch hunt par excellence, an example of what Jonathan Rauch, a journalist and researcher at the Brookings Institution, has called the “humanitarian threat” response—one of those moral crusades in which academic work is not evaluated on the basis of whether it is accurate, but condemned in the name of the harm it might do to some supposed moral cause.

In their work, Thornhill and Palmer excuse nothing and absolve no one. They simply remind people that sexual violence has something to do with biology and that ignoring that fact means—at best—misunderstanding the nature of rape and, at worst, harming victims. In the face of such heresy, the outrage machine went into overdrive. There were defamatory articles, bad-faith readings, insults, and even threats from which the researchers needed police protection. At the end of it all, both their lives had been irreparably damaged.

Of the unlucky pair, Craig T. Palmer was probably the one who was most familiar with the idea of a “humanitarian threat.” He was in his early twenties in the mid-1980s, when he gave up on completing his doctorate in anthropology. As he explained to historian of science Alice Dreger three decades later, “Postmodernism was then coming into academia and it didn’t seem worthwhile to go through all of the hard work of science and present all the evidence, just to have it dismissed by [someone] saying, ‘Well, that’s just your narrative.’” (The conversation is detailed in Dreger’s book, Galileo’s Middle Finger.) Having cut short his academic career in Arizona, Palmer set out for Maine, where he got married, bought a house, and became a lobster fisherman.

But a fateful event—the abduction of his neighbours’ daughter—which occurred shortly before he went into self-imposed exile, was to cut short his new career. The suspect was quickly arrested and, in the face of overwhelming evidence of his guilt, he confessed and, three days later, led the police to the victim’s body. The medical examiner established that the young woman had been raped, but the local press unanimously repeated that the attacker’s motivations remained unknown. In Palmer’s eyes, this showed that they were in the grip of an absurd dogma: one that forbids us from thinking of a rape—and the kidnapping and murder committed to facilitate it—as a sexual act that went terribly wrong.

When an assistant to the Arizona Attorney General called Palmer out of the blue, his suspicions were confirmed. “My first thought,” he told Dreger, “was that I must have forgotten to turn in some library book that was now a year overdue. But the assistant DA said the rape/murder [of the neighbour] was coming to trial, and his job was to contact everyone who lived in that part of town to see if he could find anyone who had seen an angry interaction between the girl who was raped and murdered and the man who was accused.”

Palmer had nothing of the sort to offer. “I was curious about why he would need someone to report that specific thing, so I asked him, … ‘Couldn’t you just argue that the guy was sexually attracted to this girl and he knew she would never have sex with him willingly?’” In other words: Wasn’t it reasonable to establish a sexual motive and conclude that she had been murdered to cover up the crime?

In essence, that was precisely what the prosecutor’s office had wanted to argue until the defence retorted that “scientists had proved that rape is not sexually motivated. Instead, it’s motivated by a desire for violence, control, or power”—and it was this motive that the prosecutor’s office now had to establish.

Palmer was furious: how could rape be presented as a non-sexual act, especially when such a poorly supported hypothesis might prevent rapists and murderers from being prosecuted? How could blind adherence to a populist dogma of this kind allow a murderer and rapist to slip through the cracks?

Palmer had scarcely hung up the phone when he remembered that he had told his thesis advisor, “If I come back [to academia], the claim that rape isn’t sexually motivated might be one obviously wrong social science explanation worth challenging.” After obtaining his wife’s permission, Palmer asked the University of Arizona to convert his resignation into a sabbatical so he could complete the remainder of his thesis on lobsters. Palmer was back.

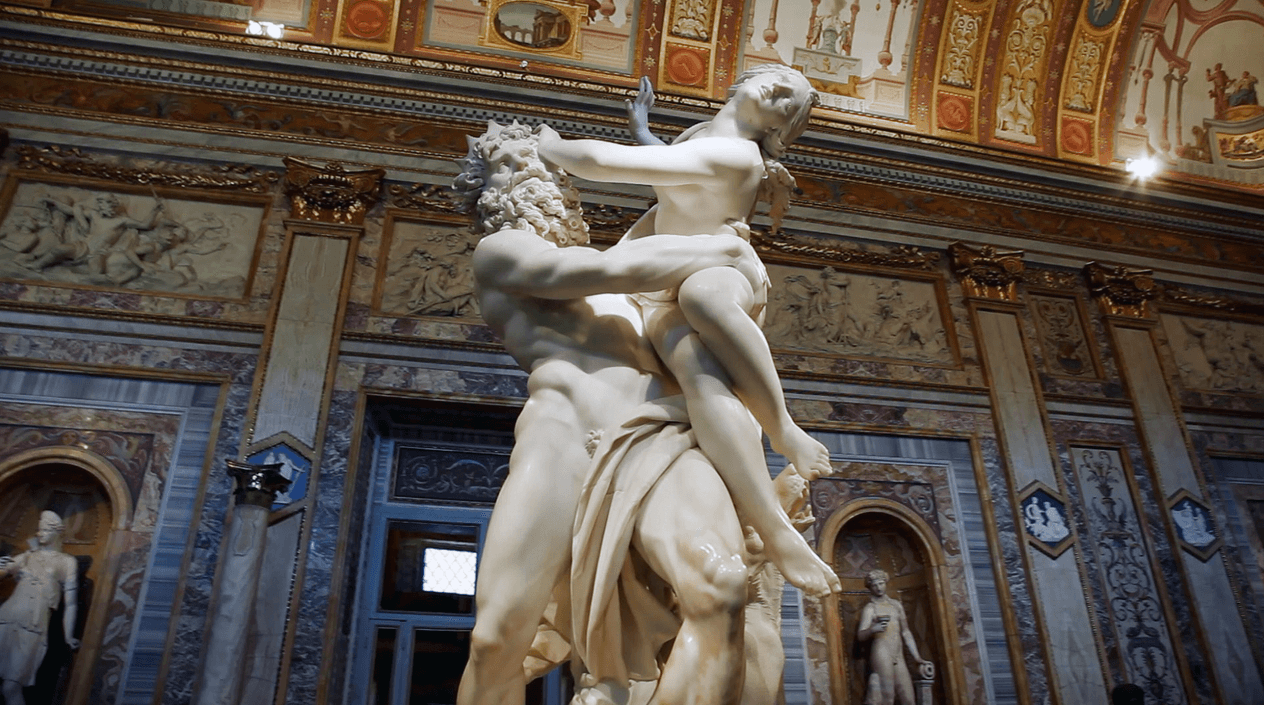

His research on the biological bases of sexual coercion inevitably led him to cross paths with the entomologist Randy Thornhill, who was studying the same phenomenon in insects, focusing on the meadow scorpionfly (Panorpa vulgaris), a species that frequently invades our gardens in summer. The male scorpionfly has two reproductive strategies. The first is to seduce the female by offering her a “nuptial gift” (a ball of saliva or a dead insect). The second is to chase her and take her by force.

And there’s one particularly salacious detail—only Mother Nature, in her infinite wisdom, could come up with something like this—the males are equipped with a specialised organ for forced copulation: a kind of pincer at the end of the abdomen resembling a scorpion’s stinger (hence the creature’s name), which holds the female in place, pins down her wings, and prevents her from escaping. Moreover, this organ seems to have no other purpose. As Thornhill demonstrated, if you neutralise the hook by covering it with beeswax, the male no longer rapes.

But while this mode of copulation is common, it’s not exactly the preferred method among scorpionflies. Female panorpids clearly prefer to mate with a “seductive”—rather than a “rapist”—male. We can tell because they willingly follow males bearing gifts and remain indifferent to those who show up empty-handed. And the males themselves also seem to prefer consensual copulation and only resort to coercion when they can’t get their hands on a suitable present. In fact, if a male who is chasing a female and is on the verge of deploying his “stinger” stumbles upon a potential gift at the very last minute, he quickly reverts to seduction mode.

Since they are not complete idiots, Thornhill and Palmer obviously know that there are major differences between humans and scorpionflies. First, to my knowledge, no man has ever seduced a woman by offering her petrified saliva. Second, males of our species aren’t equipped with an organ specifically designed for rape. Nevertheless, at a very general level, human sexuality, like that of mecopterans, is the product of evolution. So seeking to explain human rape using the tools of evolutionary biology isn’t completely absurd.

Thornhill and Palmer co-authored several studies published during the 1990s. Then in 2000, they released an article in The Sciences (a defunct journal of the New York Academy of Sciences) titled “Why Men Rape?”—a sort of mission statement for their book, A Natural History of Rape: Biological Bases of Sexual Coercion, which was slated to appear with MIT Press two months later. (Favre published a French translation in 2002 under the title, Le viol. Comprendre les causes biologiques pour le surmonter… et ne plus le perpétrer (“Rape. Understanding its Biological Causes in Order to Overcome it … and Stop Perpetrating it”).

The book, like their academic work, posits two different hypotheses. For Palmer, rape is primarily a by-product of male sexuality, especially its tendency to be notoriously indiscriminate; for Thornhill, it can also represent an authentic reproductive strategy pursued as a last resort.

Without ever choosing between these two theories—which aren’t necessarily mutually exclusive—Thornhill and Palmer compile a systematic catalogue of sexual violence in humans and other animals, focusing on the perpetrator’s perspective—though without ignoring the victim’s perspective, as their original title indicates: Why Men Rape, Why Women Suffer.

Here are a few examples of the arguments they present: the victim’s physical appearance matters to the rapist; rape is first and foremost a sexual act, and only secondarily (and not always) motivated by a desire to dominate, humiliate, or annihilate; rape can be a means for the rapist to transmit his genes; reproductive biology plays a role in sexual coercion. Both researchers hammer home the point that while certain criteria—such as the victim’s age, appearance, and vulnerability—are important to the aggressor and this explains why men rape—this can never excuse rape, much less justify it. But it didn’t matter how often they explained this—things were about to get very ugly.

Palmer later recalled his first meeting at the offices of MIT Press in Boston, in the conversation with Alice Dreger cited above. He and Thornhill had been expecting to talk marketing. Instead, they found themselves facing a packed room of fifty or sixty people. And those people were up in arms. No one wanted to discuss the content of the book—they were there to stop it from being published. Palmer jotted things down on a notepad and responded to the objections point by point. The hostility was palpable. It felt almost like facing an inquisition—as if the publishers were expected to endure a gruelling moral ordeal before they could even envisage publishing the book.

When the book came out in January, all hell broke loose. The first, rather surreal, sign of trouble was when Palmer received a message from an old friend, informing him that the famous ultraconservative radio talk-show host Rush Limbaugh had been ranting about the book. The talk show host soon lost interest, but the controversy raged on.

The playbook was always the same: attribute to Thornhill and Palmer statements they never made, then castigate them for them. Writing for Time, Barbara Ehrenreich suggested that they were trivialising the harm suffered by victims—when the book actually strives to give that its full weight. An op-ed in the Los Angeles Times argued that calling rape a sexual act amounts to normalising it.

The headlines sealed the deal: “Can’t Help It Theory” wrote the Nashville Tennessean, “The Men Can’t Help It,” wrote the Guardian. The Globe and Mail carried a string of indignant letters to the editor titled “Are Men Natural-Born Rapists?” The story seemed to write itself: if rape is a biological phenomenon, then it must be an imperious urge against which men are powerless. Thornhill and Palmer were blamed for something they never wrote.

Then they received the official stamp of disapproval. In 2004, anti-Darwinian biologist Joan Roughgarden delivered her verdict in the highly respected journal Ethology. Thornhill and Palmer, she writes, are “guilty of all allegations” and “deserve to hang.” Above all, she urges her readers to boycott their seminars and labs. The message was clear: this was about activism, not debate—she had turned what should have been an academic disagreement into a punitive campaign. “Critics of evolutionary and human-sexuality psychology should realize that they’re dealing with a political fight more than an academic dispute. We must organize as activists to oppose this junk and get out of our safe comfortable armchairs, for much is at stake,” Roughgarden concludes.

Then there were disrupted lectures, cancelled talks, protests on both men’s campuses, and their publishers were subjected to a campaign of telephone harassment to try to make them disown the authors. The witch hunt had turned into a siege. “I learned,” Palmer told Dreger, “the legal line that separates official death threats from run-of-the-mill nasty e-mails and letters.” By the end, Thornhill was divorced. As for Palmer, he told Dreger, with the clarity of the chronic depressive he would soon become:

From all this, I’ve learned more about the human species and how it can do things like lynch mobs and genocide and stuff. I’m not sure I’m glad to have that knowledge. One of my colleagues asked if the experience had lowered my view of the media. And I said no, it’s lowered my view of the species.

So where did all this vitriol come from? Thornhill and Palmer “threatened a consensus that had held firm in intellectual life for a quarter of a century,” writes psychologist Steven Pinker in The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature (2002), the first book to detail the witch hunt. This dogma—which is a hallmark of “blank slate” ideologies—posits that human behaviour in general—and the most harmful behaviours in particular—stems entirely from upbringing, learning, and socialisation.

This draws on the myth of the “noble savage,” which is itself a variant of the naturalistic fallacy: what is natural is good, and what is good is natural. Since sexuality is natural and nature is benevolent, sexuality must be good. For such people, “sex should be thought of as natural, not shameful or dirty,” Pinker notes. Since rape is undeniably harmful, it can’t be natural and therefore, according to this misguided syllogism, rape has no connection with sex: “The motive to rape must come from social institutions, not from anything in human nature.” In short, rape involves power, domination, and control—everything except desire, despite the fact that the overwhelming majority of rapes are committed with an erect penis.

It’s reassuring to note that Pinker was not the only person to raise his voice in defence of Palmer and Thornhill. In fact, importantly, some rape survivors expressed their relief that someone had finally acknowledged that their attackers had primarily been seeking sexual gratification. One such victim was Elizabeth Eckstein, who wrote an entire op-ed about Palmer and Thornhill for the Dallas Morning News. Her opening lines deserve to be quoted in full (they are also cited by Dreger):

Finally. Finally, somebody is coming around to my way of thinking on the motivations of rape. I can say this because I survived an aggravated sexual assault by a serial rapist and, more important, two years of post-traumatic stress syndrome that included an exhausting state of hypervigilance, sudden panic attacks, yelling at God and the cold clench of fear in my gut. I also was consumed with an obsessive (some would say unhealthy) need to know why. Why me? Why him? Why rape? So I tried to find out. During my quest, I came across a lot of people who liked to quote the so-called experts and say things such as, “It’s a crime of violence, not sex” and “It’s a control thing.” Boy, did I hate those people. In my mind, they were wrong. I used to reply to those sorts in a real catty fashion. “He didn’t force me into the kitchen to break all the dishes. He didn’t make me smash all the furniture in the house. He made me have sex with him against my will. Sex, people, sex at gunpoint. Choice absolutely and totally removed from the equation. An act, typically one of love, reduced to its lowest and ugliest form.”

In an interview with the Boston Herald, also cited by Dreger, Jennifer Beeman, director of the campus violence prevention program at UC-Davis, expressed her hope that Thornhill and Palmer’s work would prompt scientists, social scientists, women’s organisations, and rape specialists to reexamine their assumptions. “For so long our mantra has been, ‘It’s about power, not sex,’ that I think we’re afraid to admit it might be about both,” she conceded.

Twenty-five years later, the dust still hasn’t settled. I can attest to this personally. Because I follow in the footsteps of Thornhill and Palmer, I’m frequently accused of rape apologia. It was on these grounds that, in 2022, Sciences Po cancelled an elective course I was supposed to teach on their Reims campus—a course that had been officially approved—less than a month before it was scheduled to begin.

The Thornhill and Palmer affair is an ugly story. It is the story of two researchers who challenged intellectual orthodoxy and found themselves trapped in a world in which rumour counts as proof, the motivations falsely attributed to you matter more than what you actually wrote and people would rather punish men than refute ideas.

And there is something even more troubling about all this. It reveals just how easily a community that prides itself on its dedication to truth-seeking can turn into an inquisitorial tribunal in which the reputations and careers of those it marks out as guilty are burned at the stake. Instead of disproving ideas through a process of scientific refutation, they are destroyed by instilling fear—the fear of giving offence, of going against the grain, the fear that one’s head will end up on a pike.

Like too many academic witch hunts, the one Thornhill and Palmer endured reminds us that it’s not only the powers-that-be—religious or political authorities—who can threaten our freedom of thought. In fact, the threat more often comes from within: from the thought police among our academic colleagues. The rot has spread deep. In the name of the noblest causes, the people Jonathan Rauch called the “kindly inquisitors” have been quietly turning universities into places where you are less likely to gain knowledge than to learn how to keep quiet.

Erratum: The original text stated that Thornhill and Palmer’s article “Why Men Rape” appeared in the journal of the American Academy of Sciences, rather than in The Sciences, a now defunct journal of the New York Academy of Sciences.

This essay was first published in Le Point in French on 16 August 2025 and has been translated for Quillette by Iona Italia. You can find the original here.