Videos

Why Britain Signed a Treaty with the Māori—but Not with Australia’s Aboriginal Peoples

Why did Britain negotiate a treaty with Māori chiefs in New Zealand but claim Australia as terra nullius—“land belonging to no one”?

Adapted from Sean Welsh’s Quillette essay and narrated by Zoe Booth.

This video explores the deep historical and legal differences between the colonisation of Australia and New Zealand, drawing on historian Bain Attwood’s book Empire and the Making of Native Title. From Lord Sydney’s penal experiment to Governor Grey’s pragmatic purchases, we uncover how power, perception, and expediency—not ideals—determined who got a treaty and who didn’t.

We’ll trace how 19th-century ideas of sovereignty, property, and cultivation shaped British colonial policy, why Māori were seen as political actors while Aboriginal peoples were not, and how these choices still reverberate through today’s debates over land rights, national identity, and sovereignty.

This video is based on Sean Welsh’s review of Empire and the Making of Native Title (Quillette, 3 July 2025):

Chapters

00:00 Why These Colonial Decisions Still Matter Today

00:40 Historian Bain Attwood’s Framing of the Question

03:02 Australia’s Beginnings as a Penal Colony, Not a Planned Conquest

04:22 Early British Views of Aboriginal Peoples and Military Risk

05:13 How Terra Nullius Took Hold in Australia

05:25 Why New Zealand Followed a Treaty-Based Approach

06:41 Māori Political Organisation and the Case for Treaties

06:56 British Colonial Policy: Pragmatism Over Principle

View full transcript

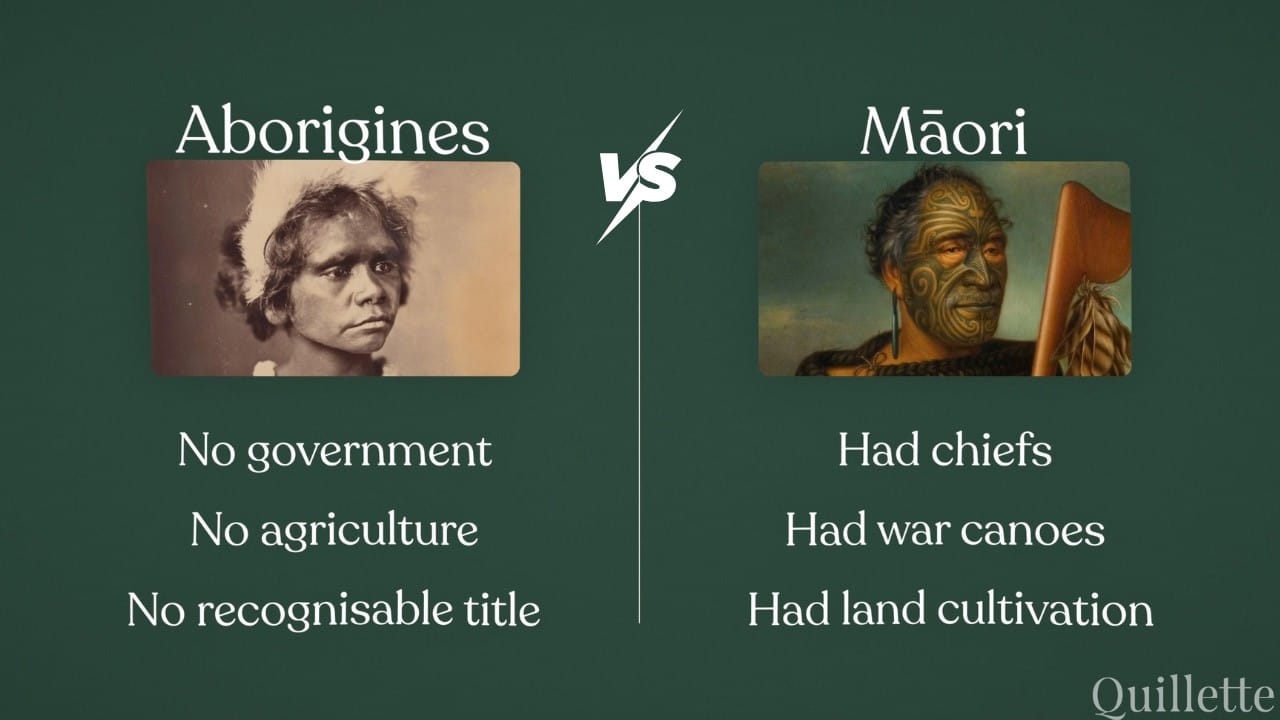

Why did Britain sign a treaty with the Māori in New Zealand, but not with the Aboriginal peoples of Australia? That question might sound academic—dusty even. But today, it's at the heart of land rights, national identity, and heated political debates in both countries. It’s written on protest signs, shouted through megaphones, and debated in parliaments. The slogans—“Always was, always will be Aboriginal land,” or “Sovereignty never ceded”—are not mere rhetoric. They're claims about legitimacy, law, and history. So what made New Zealand's colonisation "negotiated" and Australia's an act of unilateral possession? Was it racism? Ignorance? Cold pragmatism? Historian Bain Attwood has an answer—but it's not simple. In fact, the truth, like most of colonial history, is messy, contingent, and, yes, often driven by chance. Let’s begin with the surface-level contrast: in 1840, the British Crown signed the Treaty of Waitangi with Māori chiefs. But when the First Fleet arrived in Australia in 1788, no treaty was signed. Sovereignty was simply declared. That difference has led many to believe that Britain recognised Māori sovereignty but denied it to Aborigines. The reality, as Attwood shows in Empire and the Making of Native Title, is far more complicated. For starters, sovereignty and property are not the same thing. When Britain paid the Noongar people to extinguish native title over a vast swathe of Western Australia in recent decades—200,000 square kilometres—they got compensation, but no acknowledgment of sovereignty. It was a land deal, not a political settlement. Meanwhile, in contemporary Canada, King Charles recently acknowledged “unceded” territory. Surprising? Perhaps. But while Canada signed over 70 treaties with its Indigenous peoples, Australia signed none. The phrase terra nullius—literally “land belonging to no one”—wasn’t about population. It was about legality. The Aborigines were seen as lacking the institutions necessary to own land: no government, no agriculture, no recognisable title. And as such, no one to make a treaty with. That wasn’t how Māori society was viewed. They had chiefs, war canoes, and, crucially, land cultivation. They sold land, made treaties, and fought in wars. And they won them. At Ōhaeawai (Oh-ha-way) in 1845, Māori inflicted a humiliating defeat on a British force more than six times their number, artillery included. When Governor Grey arrived shortly after, he took the pragmatic route. He bought more than half of New Zealand from Māori—32.5 million acres—for less than half a penny an acre. But this wasn’t generosity. It was strategy. Compare this to Australia, where the founding of New South Wales wasn’t a grand plan of conquest or a humanitarian mission. It was a prison solution. Britain had just lost America, its most useful dumping ground for convicts, thanks to the Revolutionary War. With the prisons overflowing and no more colonies across the Atlantic to absorb the overflow, Lord Sydney, Britain’s Home Secretary, needed a solution. Fast. Sydney wasn’t some cartoon villain twirling his wig. He was, in his own words, a man of “benevolent mind.” His aim? To spare lives from the gallows and, perhaps, make them useful again. He envisioned a penal colony that would not merely punish, but reform. It would also, he hoped, yield commercial and political advantages in the long run. To make it happen, Lord Sydney chose Arthur Phillip, a capable Navy Captain he'd previously worked with during his stint as Secretary for War. Phillip had been drawing up plans to invade Spanish America. Though that military expedition never materialised, Phillip was repurposed. His new mission: to lead a voyage to the far side of the world and establish Britain’s newest colonial experiment. But make no mistake—this was not an invasion in the Napoleonic sense. No redcoat legions, no thunderous artillery. Just a few hundred marines, a ragtag fleet, and a hope that the locals wouldn’t resist too much. And why would they? According to Joseph Banks and James Cook, the natives of New South Wales were few, scattered, and not a serious military threat. Banks even described their canoes as “wretched,” their mode of subsistence as rudimentary, and their presence inland as unlikely. In other words, there was no one to negotiate with. No cities. No forts. No obvious leaders. No agriculture, at least none that colonial eyes recognised. And certainly no centralised system of land ownership. From the British perspective, this wasn’t a sovereign people—it was a wilderness. So when Britain planted its flag in Australia, it didn’t ask for permission. It didn’t sign treaties. It simply declared possession. And this decision—to treat the land as terra nullius, belonging to no one—would shape the legal and moral battles of the next two centuries. In New Zealand, things evolved differently. Settlers arrived before the state did. They traded, they bought land from Māori chiefs. By the time the British Crown got involved, it had to formalise these arrangements to prevent chaos—and, crucially, to fend off the French. That urgency led to Captain Hobson’s mission to get a treaty signed in 1840. And he did. Sort of. The Treaty of Waitangi wasn’t universally understood or immediately revered. Some called it “a praiseworthy device for amusing and pacifying savages.” But it served its purpose: stalling French ambitions and regularising British control. In Australia, however, when John Batman tried to buy land from Aborigines in 1835—a sort of DIY treaty—Governor Bourke swiftly declared it invalid. Only the Crown could own land. The Aboriginal people had no title to sell. The prevailing logic was Lockean: title came from labour, cultivation, and improvement—not from merely living on the land. And yet, that Lockean view was not applied universally. In North America, the British had long recognised treaties with tribes, not out of generosity, but necessity. Native groups there were numerous, militarily capable, and politically organised. The British needed peace as much as land. Treaties provided both. By contrast, in Australia, the colonial project required neither. Still, the idea that the British were acting out of coherent legal doctrine—rather than expediency, fear, or convenience—is one Attwood rejects. His picture of history is less idealised. He portrays the making of native title not as a principled process but a contested, erratic scramble shaped by politics, economics, and bureaucratic improvisation. The notion that the Crown “should have” recognised native sovereignty because of certain Enlightenment ideals is, in his view, a myth retrofitted to history. Even the Treaty of Waitangi didn’t emerge from high principle. It was a patchwork response to commercial, diplomatic, and military pressures. And its significance evolved only later, often reshaped by the needs of courts, activists, and historians. Attwood’s work dismantles tidy narratives and urges us to confront the uncomfortable truth: colonisation was neither wholly conquest nor wholly negotiation. It was, in Australia’s case, a slow-motion land grab justified by legal fictions. In New Zealand, it was a more contested transaction—at times exploitative, at times pragmatic, but never consistent. In the end, the story of who got a treaty and who didn’t wasn’t shaped by justice, ethics, or Enlightenment ideals. It came down to who had cultivable land, who had firepower, and who could negotiate—or resist—on Britain’s terms. It wasn’t moral philosophy that drove colonisation. It was maritime logistics, imperial budgets, and political expediency. Has learning more about this history changed how you feel about the idea of Australia signing a treaty with its Indigenous peoples? Let us know in the comments. This video was based on Sean Welsh’s review of Empire and the Making of Native Title: Sovereignty, Property and Native People by Bain Attwood, published in Quillette on July 3rd, 2025. Thanks for watching, I’ve been Zoe Booth.If you found this video essay useful, subscribe to the Quillette YouTube channel and browse our video archive.