Political Philosophy

After Liberalism

The core principles of liberalism—freedom and equality—are insufficient for the good life. We need to supplement them with a more robust, metaphysically thicker understanding of human nature and the good.

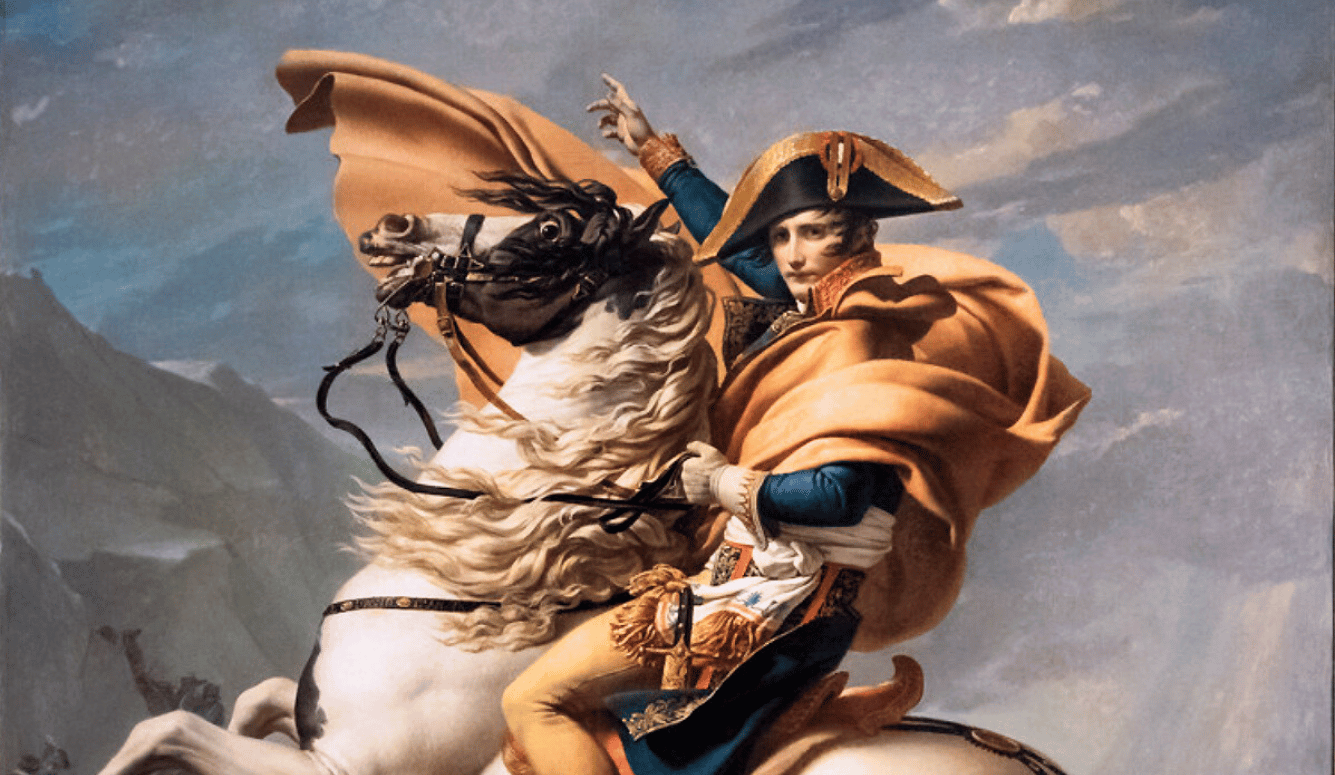

Witnessing the world conflagration that was the French Revolution, the French philosopher Joseph de Maistre lamented that “if there is an incontestable maxim, it is that in all seditions, insurrections, and revolutions, the people always begin by being right, and always end by being wrong.” Faced with serious political crises, many contemporary elites have come to believe that the people do not just end by being wrong but begin so. The voice of the people is no longer to be listened to but controlled, corrected, channelled, or outright suppressed.

The postwar liberal consensus of some eighty years standing is currently breaking down. There is a general sense of malaise and of the crumbling of old certainties. Many have begun to question the viability of democracy in the modern age. Democracy has indeed always had its critics. The ancients considered it a weak and inherently unstable regime, hovering perilously between anarchy and tyranny, and prey to ignorance, demagoguery, and the excesses of passion. It was generally disdained until the Age of Revolutions in the late eighteenth century. John Adams could still warn in 1814: “remember Democracy never lasts long. It soon wastes, exhausts and murders itself. There never was a Democracy yet, that did not commit suicide.” It was only over the course of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries that it gained its respectable sheen of representative government and liberal constitutionalism.