Israel

Inside the Gaza Humanitarian Foundation’s War-Zone Aid Operation

An in-depth interview with Chapin Fay of the Gaza Humanitarian Foundation on delivering aid in a war zone—and why their unconventional model has drawn both praise and criticism.

In this extended interview, Quillette’s Pamela Paresky speaks with Chapin Fay, spokesperson for the Gaza Humanitarian Foundation (GHF), an independent American non-profit delivering emergency food aid to Gazans amidst ongoing war. Fay describes how GHF has distributed more than 170 million meals in just four months—without diversion or theft—and explains why their unorthodox model, which includes armed protection and local staffing, has drawn both praise and controversy. He also addresses criticisms from the UN and outlines the complex logistical and moral landscape of operating in one of the world’s most fraught humanitarian environments.

Transcript

Chapin Fay: GHF, as it’s known, is an independent, neutral American non-profit, with one mission and one mission alone, which is to feed the people of Gaza in a way that no one else can steal it. We’ve done it to the tune of over 170 million meals put directly into the hands of the people who need it most, in less than four months.

Pamela Paresky: What was the typical distribution for humanitarian aid before you were involved?

CF: So, one of the reasons GHF was created was because the legacy system in Gaza had failed. The government of Israel had lost faith in it for many reasons, the main of which was diversion of aid. Whether that was Hamas stealing it, other armed gangs stealing it, or some other type of diversion, the aid wasn’t getting to where it was supposed to be. It was furthering Hamas’ war efforts. And there was a lot of politics involved in the situation. So we came out of a call from President Trump for innovative solutions. I believe he made that call last autumn. There were plenty of strange, wacky ideas that came out of that for a couple of months. And then we were incorporated in Delaware as a non-profit in February. And we began food distribution at the end of May of this year. And we would describe ourselves as an emergency food distribution operation.

PP: What was food distribution like when it did get to where it was supposed to go before you got involved?

CF: So I don’t want to speak for the legacy system, aid organisations. I’m not sure much of it got to where it was supposed to.

PP: But I mean, did they do the same thing that you do? Sorry, once it got to that...

CF: Point? Yeah, good question. We have a pretty unique model and a different model, which is one of the reasons the legacy system is one of our biggest critics. We have secure distribution sites. We have four of them. We’re supposed to have eight of them throughout Gaza. We rely on the IDF to build, de-conflict, and create humanitarian zones and then turn the sites over to us. We push them every day to get us to at least the original eight. We also only operate from central Gaza to the south. We do not operate in the north, where the need is greater.

PP: Why is that?

CF: It’s more populated. So we are within reach of about a million Gazans, where we are located.

PP: About half, right?

CF: Right. There are over two million Gazans and a lot of them are in Gaza City, in those areas. It was also the last Hamas stronghold. So the IDF has already secured, for example, Rafah, where some of our sites are.

PP: Southernmost.

CF: That’s right. It used to be a Hamas stronghold and it is no longer. The IDF has basically turned it into rubble and created the space, and we built our sites. Now we distribute food mostly to people who are from the area. Though over the past couple of weeks, with the intensified operations by the IDF in the north, we have seen an influx of people to the south. But our model is unique. We have safe distribution sites—that’s one unique aspect. The second is we employ local Palestinians on site. They run each site and are the first to deal with and organise the crowds of aid seekers and distribute the aid.

PP: Is that safe for them?

CF: It is not. It’s a very dangerous job. They live on site now and they cover their faces. They’re also unarmed and don’t wear protective armour by choice. But they live on site because of a very tragic incident that happened in mid-June of this year. They used to take a bus to work, to our sites. Hamas hijacked one of the buses, murdered nine on the bus. A crowd got them to flee, and the rest—about 20-21 survivors—were left at Nasser Hospital. They were refused treatment and left to die in the parking lot—these are Gazans—solely for having the audacity to help us feed their friends, neighbours, and families. So yes, all of them now live on site. They work alongside our humanitarian team.

PP: Before you go further, I just want to go back to that incident and understand what happened. The crowd got Hamas to run away, or the crowd got injured?

CF: Hamas injured people. Hamas fled the scene.

PP: I see.

CF: I was not there. I was told it’s because there were too many others, non-Hamas people. So Hamas came, they hijacked the bus, they shot some people, and then they fled. The remaining survivors—I think almost two dozen—were then brought by their fellow Gazans to Nasser Hospital.

PP: And people might argue, well, there weren’t enough doctors at Nasser Hospital. Maybe that’s why they didn’t treat them.

CF: Yeah, you would have to ask them. We believe that they—I mean, they weren’t even brought inside. We have heard reports that there aren’t enough doctors, there isn’t enough medicine. We can go into that later. But this is one of the most complex humanitarian crises of our lifetime. It’s happening in an active war zone. You just saw a coup about a month ago. The IDF attacked Nasser Hospital because there was a threat there.

PP: We’ve all read reports that hostages were held there at one point. And when this incident happened, was there any sort of medical humanitarian organisation working there?

CF: Doctors Without Borders is based there. I don’t know if there are any others. But they definitely operate out of Nasser Hospital.

PP: So they would’ve been aware that there were...

CF: Presumably...

PP: People seeking help?

CF: Presumably. Again, they were not allowed inside. They were left to die.

PP: And so now your Palestinian workers want to stay inside the secured area?

CF: Correct. Yes. Our sites are guarded 24 hours a day by a security team that lives there when they’re on duty. And also by our threat assessment team at our operation centre near the Kerem Shalom border, that monitors, via cameras, our sites 24 hours a day. Their main job is threat assessment. We work with the IDF. If the IDF tells us there is a Hamas threat in the area, we will close the site or not open it.

PP: If the threat is going to be to aid seekers or your people, you close it temporarily until the threat is clear?

CF: Yes. Our most northern site, SDS4, is closed every couple of days because it is near a hotspot. Logistically it’s complicated. There are structures for people to hide under. And there have been threats, IEDs located, and the IDF is taking care of them outside the site. We’re responsible for the safety and security of everybody, including, and especially, the aid seekers on our sites. And the IDF, of course, is responsible for the humanitarian zones and the rest of Gaza.

PP: Have you considered moving that site? That one doesn’t seem to be secure.

CF: We are opening another site, not near there, but we are opening a bigger site. Site 1 is also closed to be rebuilt. It has been rebuilt and we’re in the final stages of checking security and logistics, making sure it will be okay for the aid seekers—logistically and safety-wise. That should be open within a couple of weeks. And that site will move to continuous distribution, which will help bring the pressure down in the areas where we’re operating. It’s like two of our sites next to each other.

So like I said, we have local workers who work alongside our humanitarian team. The humanitarian team includes a lot of USAID folks, people from the UN, and all sorts of INGOs. Their job is to make sure that our aid is delivered and distributed in a humane, dignified way. They’re not all Americans. One of the top humanitarian leaders at GHF is from France. Our team comes from all over the world, and many have done this for decades.

We also have security personnel who are highly trained, skilled, experienced, and more importantly, intelligent US military veterans, typically former special forces. One of the main Hamas threats is that they try to provoke us into shooting at a crowd. So it takes a lot of poise and training to know when not to do that. None of our security personnel have fired a bullet at anyone during this engagement, regardless of what you may have read.

We have two to three sites operational each day. We have only missed three days since we started on 26 May. One of those was at the beginning of the Rafah War. Another unique part of our model is that we control our supply chain from beginning to end. We vet our suppliers very thoroughly. One of the problems with the legacy system was corruption and smuggling. We don’t allow for any of that. We’ve turned down many potential suppliers because it was clear they were in it for something other than delivering aid.

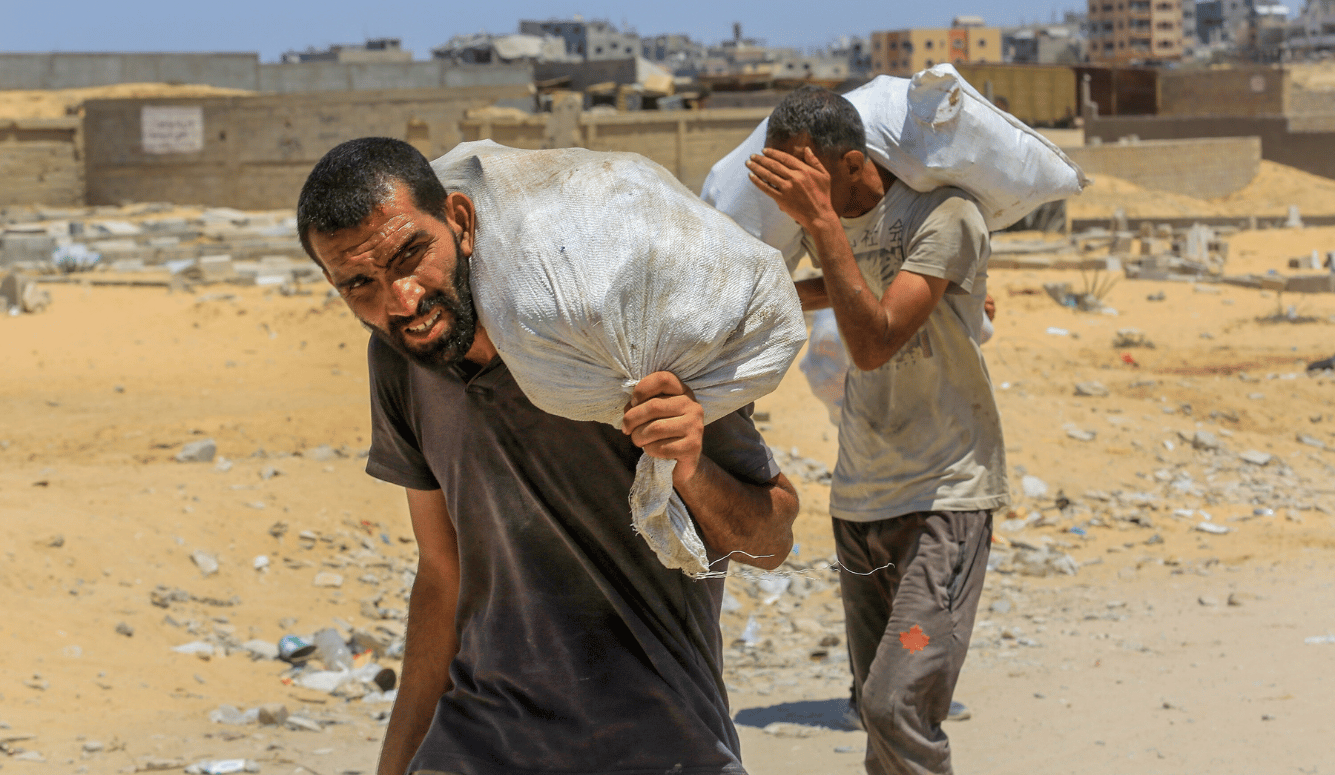

We find bulk suppliers. The supplies go to a warehouse between Tel Aviv and Kerem Shalom, where we de-package the goods into GHF boxes. I was just at our warehouse the other day. It’s really impressive. People take bulk flour or lentils, put them into family-sized bags, and then into boxes. Our boxes have 42,500 kilocalories. They are designed to meet or exceed UN and INGO humanitarian aid standards. But they’re also meant to be carried home, particularly by women. Each box contains enough food for a family of 5.5 to have three meals a day for 3.5 days.

We’ve delivered over 2.8 million boxes. That’s how we get to over 170 million meals delivered. When I say we’ve put 170 million meals into the hands of the people who need it, I mean literally into their hands to take home. It’s different from the legacy system. For example, the United Nations distributes bulk flour—giant bags of flour on lorries. We support different methods of distribution. It’s not a criticism—just a different way.

PP: So when they did that, who got that flour? How did it get into the hands of the people?

CF: You hear a lot about how we replaced the United Nations system. We did not. We were never meant to. We were supposed to be one part of a much bigger, more complicated solution to a very complex problem. GHF supports more aid getting into Gaza. We push the IDF and the Israeli government every day to allow that.

In fact, when they approved us after the blockade as one of the first organisations allowed to operate in Gaza, we pushed publicly for them to allow the United Nations in as well. The UN had, at one point, 1,400 community distribution points. That bulk flour, for example, would go to a market, a family, or a local INGO and be distributed that way. That’s one way to do it.

Our method is a little different. We have our own sites, which are bigger than a market or shop. We serve up to 10,000 Palestinians every single day at each site. Our lorries, loaded with GHF boxes, come in accompanied by armoured lorries with armed security personnel. These vehicles are defensive in nature—they don’t have weapons mounted like an IDF Humvee.

The aid is unloaded from the lorries by forklift operators, mostly local Palestinians. Then the convoy returns across the border. For a 9:00 am distribution, a mobile team enters earlier with the humanitarians, myself if I’m going, and media or street personnel. There’s a security and medical briefing, and then preparations are made to let the Gazans into the site. The IDF holds them behind their lines, then lets them behind the lines to enter our site. I’m not aware of many militaries who would do that—let 10,000 Palestinians behind their lines. They come in, take their boxes, and leave.

Communication and consistency are among the most important parts of a humanitarian aid operation. The humanitarian team’s job is to interact with the crowd. They hold focus groups, bring, for example, twelve women into a room privately, and the women humanitarian officers ask questions to ensure they’re getting what they need, and that it’s being done in a dignified manner. Many of our methods were suggestions from the aid seekers themselves.

One small example is the flag system at two of our sites. A red flag means we’re closed. When we open, the flag is raised green so that aid seekers can see the site is open.

GHF is committed to innovation. One problem with the legacy system was a “my way or the highway” attitude. At GHF, we’ve adapted almost every day to the dynamic environment and the needs of the aid seekers. We’ve built a two-way trust. They trust us to be consistent. If they didn’t get anything one day, they know we’ll be open at 9:00 am the next day.

We’ve also been transparent about challenges. Every aid organisation operating in Gaza is facing logistical issues. It’s a complex and dangerous war zone. One challenge we recently started solving was that in our model, younger, fitter men could rush in, leaving women, children, the elderly, and disabled behind. So now we have women’s distributions.

About six weeks ago, we began holding back aid and distributing the first portion to whoever came in first, typically men. Once they were gone, we then put aid directly into the hands of women. We are now up to 6,000 women a day at two of our sites. Women organise themselves. They come in, sit down, and we have volunteers. A deaf woman, for example, organises her friends and neighbours daily at SDS2. It’s really incredible to see.

We couldn’t do this without the trust we’ve built. Another INGO, Samaritan’s Purse, has been working with us on-site for about six weeks, delivering medical aid. We’ve never refused medical help to anyone at our sites. There are often heat injuries. There are many pregnant women with specific needs. Samaritan’s Purse takes care of that.

Before they were on site, it was highly trained medics, 18 Deltas from the military, who now work alongside them. Last time I was on site, I saw a teenage girl, all smiles in the Samaritan’s Purse tent. She was overwhelmed by the war zone. She came just to sit in the tent, get shade, a drink of water, and decompress. She knew the Americans were there, and she was safe. That was emotional to witness.

Seeing Palestinians, humanitarians, and security personnel all working together is incredible. Samaritan’s Purse has also contributed ready-to-use supplemental food (RUSF), nicknamed Plumpy’Nut. It has to be handed out individually because too much can cause health issues. We hand it out during the women’s distributions. We’ve handed out nearly a million packets over the past month.

We have a few pilot programmes for RUSF. We’ve vetted some women to take bulk RUSF to their families and communities. We use a reservation system during the women’s distribution. They receive an ID card and can reserve aid. That system is highly encrypted and air-gapped. The only use is to ensure that if someone reserves a box for Tuesday, they get it. We’re told there’s a lot of gratitude for that because they no longer have to run or race. They know the aid will be there.

Our goal is to expand this into a “super site” so that all distributions resemble the women’s model. You show your ID card, get your aid, and if there’s an issue, resolve it at another table. It’s safer and more orderly for everyone.

PP: That way people can reserve exactly the amount they need.

CF: Exactly.

PP: And then that box is packed for them?

CF: And it’s safe for them when they are guaranteed to get it. Our sites are open for a couple of hours a day per distribution. Sometimes we do double distributions at sites, so they’ll be open anywhere from two to six hours. Putting aid into the hands of 6,000 women takes a couple of hours on its own.

We want to get to a point where Site 1 is open for sixteen hours. So you don’t have to rush to get there at 9:00 am. You can come at 10:00, 11:00, or any time during the day and still get your aid. That will help bring the pressure down. It will be incredibly helpful now, since the environment is more dynamic because of the northern offensive sending more people south.

I think that gives a good understanding of our model. Again, it’s a little different. The United Nations does bulk aid. GHF supports many more aid organisations operating.

PP: I’m confused about how that works. Your system is easy to understand. A person who needs food comes and gets food. The UN distribution—I understand that a lot of the aid ended up being sold. So people would go to a market and pay for food that should have been free. But if it had gotten to where it needed to go and it was in bulk, did they open it up and hand it out? Or do they give a giant bulk bag to someone to carry home?

CF: The first thing I’ll say—something I forgot to mention—is that on our first day of operation, aid seekers couldn’t believe it was free. Many refused to leave the site because they were worried they had to pay or were in some sort of trouble for not paying. They just couldn’t believe it. So you’re right. There were many problems with the legacy system, the main one being diversion and the aid being sold by Hamas at prices their fellow countrymen couldn’t afford. There was price gouging. We’ve all seen footage of Hamas members not starving, to put it diplomatically, in their tunnels.

Currently, the UN has been operating in Gaza since May, just as we have. They’re having trouble getting their aid to where it needs to go. You can look on the UN’s own website. They have a tool with all sorts of metrics. Their overall average over the last four months is somewhere around 88 percent of aid not getting to where it was supposed to go. That’s 88 percent diversion.

PP: Have they been able to track what happens to that?

CF: They do not track where it goes or who took it or how it didn’t get there. They just track that it didn’t reach its intended destination. We’ve had zero diversion. Our aid convoys haven’t even been attacked. The Hamas threat for us really comes from their fellow Gazans—the aid seekers—and protecting them. They are under threat for being at our sites, and of course, so are our security and humanitarian local workers on site.

There have been two terrorist attacks on our sites.

PP: What happened?

CF: The first was over the 4th of July weekend. A ball-bearing Iranian Hamas-style grenade was thrown over the berm at one of our sites. It injured two American workers, who are okay now. The second was the only incident of casualties on our site. It was a really tragic and unfortunate day when Hamas fomented a stampede. One of the reasons we have armed security personnel is to protect the crowd from itself. A big crowd is dangerous and hard to control.

The IDF has its methods, which we believe are less safe than American methods. We criticise them publicly and push them privately almost every day to do things more safely. Hamas fomented a stampede and nineteen aid seekers were tragically trampled to death.

We identified a Hamas agent in the crowd. He had been there a couple of days casing the joint. The same thing happened with the grenade. For a couple of days prior to the attack, little kids were coming and throwing rocks over the berm of the guardhouse. Then one day, one of the things thrown was a grenade.

PP: How does somebody foment a stampede?

CF: You can push people from behind. They did that. We had to shut down a couple of women’s distributions when we first started them because they sent men. There is always an active disinformation campaign. We didn’t have regular distributions in the beginning because of the civil war zone. We tried to communicate as best we could through social media. Many people have their own devices—Telegram channels. The flag system is part of that communication, along with word of mouth.

Hamas would spread false information, like saying we’d open at 7:00 am instead of 9:00 am to build up the crowd in a war zone, which is dangerous. It’s also dangerous for people on site. Our first distribution was not pretty because we didn’t understand how the crowd would behave and they didn’t understand how we were trying to operate. So 10,000 people rushed the site. It did not look good.

But now we’re transparent about our challenges and we’re trying to solve them in a humane way. You now see 6,000 women lining themselves up, sitting down in the middle of the site, joking, smiling with the security personnel, humanitarians, and local workers. It’s quite a sight.

You can do many things to rile up a crowd. That’s what Hamas did. I don’t know that they’d be able to do it now. We actually rely on aid seekers. A lot of the threat assessments come directly from them. They tell our people when there might be a threat in the area or if someone is acting strange.

I want to point out that our security personnel—and there are women former soldiers on our team too—have never shot a weapon at anyone. They have used non-lethal methods to disperse crowds, but they’ve never shot anyone. They have fired into the air a few times. On the day of the stampede, a former Marine fired into the air so he could run into the crowd and save a child’s life, which he did.

That same man had a pistol pulled on him by the Hamas agent. He didn’t raise his weapon. He ran at the guy, tackled him, and wrestled the gun away. The Hamas agent fled back into the crowd. A lesser-trained soldier might have fired into the crowd.

Our personnel are not hired because they can pull a trigger. They’re hired because they know how not to.

Multiple people’s lives were saved that day, including one of our US security contractors who was dragged into the stampede. A half-dozen female Gazan aid seekers came to his rescue and pulled him to safety. These are the kinds of stories happening on these sites: Gazans, Americans, and internationals working together to feed people.

We haven’t had any violence on site other than those two examples. The trampling incident is the only case of deaths on site. Our security personnel are there to ensure everyone can be fed in a safe, dignified, humane manner. They have never shot anyone. In my opinion, they never would.

PP: You were talking a little earlier about the people who work for the Gaza Humanitarian Foundation. You said they’re not all American. Are any of them Israeli?

CF: I don’t think we have any Israeli employees. Also, Israelis are not allowed into Gaza. We’ve brought in media and had issues when an Israeli cameraman wasn’t allowed in. So, no, I don’t think we have any Israeli employees.

We also do not have the IDF on our sites. They never have been. Of course, they are outside the sites because that’s their area of responsibility. We’re sometimes accused of being an Israeli organisation. As I said, we are an American non-profit, incorporated in Delaware. We have no relationship with the government of Israel, other than being approved to operate in Gaza—just like the UN and any other INGO.

We work with the IDF to de-conflict outside our sites. One of the dangerous parts of our operation is that our sites are in central and southern Gaza, where the IDF operates. We have to communicate our movements every step of the way to prevent friendly fire and ensure the IDF on the ground knows a lorry full of food and our team is coming towards them. So yes, we work with them in that regard. But we don’t have Israeli employees and we do not take money from the Israeli government.

PP: Your story about the injured workers reminded me of videos circulating of Palestinians in Gaza accused of being collaborators, who are being murdered—publicly executed. Some of the videos are horrific, showing beatings, people having their legs and arms broken with large objects. What’s the security situation like for the people who seek aid? The people working for you now live inside your compound because they’re so unsafe. Given that Hamas has been so against your organisation, is it a concern that Hamas might come after aid seekers too?

CF: There’s no question it’s an issue. But many of the aid seekers we speak to, who come to our site every day, have very negative things to say about Hamas. I was struck by that. I thought they’d be more reluctant to speak out. But to a person—and I’ve been there a couple of times a week for the last two months—every single one of the dozens I’ve seen in interviews and focus groups said they understand that Hamas is the reason they’re in this position.

They have a lot of praise for America. They trust our organisation and the Americans to do the right thing, which is encouraging to see. But there is no question these are desperate, hungry people living in a war zone. As I said, we push the IDF to operate more safely, but they are waging a war. We don’t dictate war tactics to the IDF.

I was once asked by a reporter we brought to a site: on the way out, he said, “I just witnessed what I would call a very successful distribution. Is it frustrating for you to hear someone may be injured on their way home?” And we said: of course it’s frustrating. Our local workers, humanitarians, and security personnel risk their lives every single day just to put food into people’s hands.

So yes, when things are more dangerous than they should be, we are very frustrated, and we push back very hard. It’s a dangerous place. It’s an unfortunate situation. I’m not here to editorialise. The four humanitarian principles are humanity, neutrality, independence, and impartiality.

We call for a ceasefire. But it’s for politicians and warring parties to come to terms on that. We’ll continue feeding people to the best of our ability until the full need is met.

Yes, it is dangerous. I’m sorry to be repetitive, but this is the most complex humanitarian crisis of our lifetime, and it’s happening in a war zone. People come to our sites and then have to go back to living in that war zone. Your heart goes out to everyone.

That’s why our men and women do this work every single day. On my first trip there in early July, I was in one of our lorries on the way in. The security personnel were just discussing ideas to make things safer and more efficient. One of them, a tall guy with tattoos, a former special forces soldier, turned around and said: “We just want this to work, man. We just want these people to go home with food.”

That’s the mentality everyone on site has. Unfortunately, it’s happening in a war zone. That’s why we have security personnel: to protect not only the aid but also the aid seekers and everyone else.

PP: It’s also happening in a propaganda war zone. What have you been most surprised about regarding the accusations about what you’re doing? Did you think this was going to be obviously good, and so therefore people wouldn’t make things up about it?

CF: My joke is: who would’ve thought feeding people would be so controversial? So yes, I was a little surprised by that. I’ve always followed Middle East issues, especially around Israel, so I knew things would be inflamed, emotional, and politicised. But I’ve been struck by the intensity of it.

I come from politics, government, and PR in America, so I’m used to the so-called biased media. In the US, if you confront a reporter about something inaccurate, they may grumble or involve a lawyer or editor, but they usually do something to make it right—even if it’s not enough.

I have never seen anything like the international media coverage of this conflict. When confronted with outright falsehoods, many still go ahead and print them. I’m not defending it, but this is a highly politicised, emotional situation. That’s been unfortunate.

I knew the media could be difficult to deal with—that’s what I’ve done for thirty years. But I was struck by the intensity. I do think the government of Israel and the IDF are not very good at communicating. I also think GHF has been too cautious in our own communication. I’ve pushed for more transparency and to bring more reporters in.

Right now, reporters are banned in Gaza by the Israeli government. Occasionally they are allowed in. But I push every day for more people to see what we’re doing.

If you went to a site tomorrow morning, you would see people running in, taking food. There’s a bit of controlled chaos at the start when men run in and grab boxes. But then you would see 6,000 women sit down, get handed a box, and walk out calmly.

PP: What does that process look like? The women and children come after the men?

CF: Yes, for many reasons. As I said, they get left behind. It’s a challenge we were trying to solve. We’re not perfect, and we’re happy to admit mistakes and address challenges.

In the beginning, the fitter, faster men had an advantage, and women and children sometimes got left behind. One of our limitations is that we can only fit so much aid in a site at once. We have one distribution, and when the aid is gone, we close the site.

Another reason our model works—and why we haven’t had diversion by Hamas—is that, if you divert a UN lorry, it’s enough flour to feed or finance you for weeks. Our convoys are protected, so you’re not stealing a GHF lorry. That hasn’t even been attempted.

On the way out, you’d have to steal thousands of boxes from thousands of people to have enough for resale or military use. Culturally, it’s much harder to take something a woman owns. Logistically, even Hamas doesn’t have the capacity to do that at scale.

That’s why we have forklifts. We keep the aid behind a barrier where it can’t be seen. When all the men have left, the forklifts bring the women’s aid. That’s why the women sit down and wait. They’re waiting for the crowd to disperse.

The men now know they can mill around for hours, but nothing is going to happen. We haven’t used any crowd-control tactics—even non-lethal ones—for weeks since I’ve been out there.

One of the challenges we’re currently solving for is at one of our sites, where there’s a long road, almost a kilometre. When you hear there was a casualty within a kilometre of SDS3, it’s false. The IDF is more than a kilometre away. The aid seekers are more than a kilometre away before the gates are opened.

They wait behind IDF lines, then travel down this kilometre-long road. Now there are motorcycles and donkey carts. They get there very quickly. The men are done and leaving while thousands are still coming in. They zip back through the crowd on motorcycles—which is dangerous.

Our security personnel are out in the chute to stop that from happening. Everything they do is to protect the crowd first, and of course everyone else on site.

PP: Just to conclude, what’s the situation now vis-à-vis the UN’s distribution and your distribution? Are there any other organisations considering doing other kinds of distribution? Are there still airdrops? What’s the lay of the land, so to speak?

CF: Let me start with GHF. We are an emergency food distribution operation. That’s just one small part of a broader humanitarian effort. Fuel, water, baby food—and with winter coming, winterisation products—all need to be distributed.

PP: Does it get cold there?

CF: It gets rainy and muddy for sure. We currently distribute in cardboard boxes, which is a problem we’re working on. We’re collaborating with Samaritan’s Purse to distribute winterisation products that they’ve distributed before. We’re also working with them to build wells at our sites so we can do continuous water distribution.

There are other things Gazans need, like baby formula. That’s a different kind of RUSF. It’s more complicated. You can’t just pump in baby formula without doing it in a careful way. There are other NGOs handling that in Gaza.

PP: Wasn’t there just a truckload of baby formula that was commandeered somehow?

CF: Yes. It’s unfortunate. The way I describe it is: there’s nothing humanitarian about some of these other systems. Our model is working. That’s why we have an open offer to work with anyone. We’re happy to have at least a meeting. And I’m confident our lifelong humanitarians and theirs can figure out a good way to do this.

PP: There was a period where I recall seeing images of pallets and pallets of food and other humanitarian items that had crossed into Gaza but were not being distributed. Why was that?

CF: You’ll have to ask those organisations. They—and the media amplifying them—said Israel wasn’t allowing them into Gaza. But that wasn’t true. I was there. It was right when I first arrived. I think it was one of my first couple of weeks.

There were about 1,000 lorries sitting in the sun. That’s a lot of aid. I personally saw rice from Jordan cooking in the sun, and medical aid that was already expired. I think the reasons were political. It was an issue of execution, not access.

Once Israel allowed reporters to see the lorries, there was media pressure for the UN to start moving the aid. That aid was already inside Gaza. Their own metrics at the UN show it’s very difficult for them to get their lorries where they’re supposed to go.

PP: Is that over now?

CF: The government of Israel approves the UN and other organisations to move lorries into Gaza. Nobody thinks it’s enough—including GHF. We push them to allow more. We want to do more. We push them to let us expand.

You mentioned the baby formula lorry that got commandeered. That’s an example of diversion. We’ve had zero diversion. That was part of our mission: to feed people in a way that Hamas or anyone else can’t divert. We’ve successfully done that.

During my first trip into Gaza, we stopped so I could see those lorries sitting there. We spoke to a couple of lorry drivers. They weren’t UN proper—I think they were under one of the umbrella organisations—but they said it was one of the most dangerous jobs in Gaza: being an INGO lorry driver. Except for ours, of course.

The UN uses local Palestinian lorry drivers, just like we have local workers running our sites. They told us that the day before, they tried to move their lorries and were immediately shot at. They were going to be killed or kidnapped. One of the lorries was taken, and they ran back to a safer area where the lorries were. They asked us if we could provide security. I was standing there with our security guys, and our answer was: yes, of course. Talk to your leadership.

We’ve made that offer publicly. Reverend Johnny Moore has had meetings that we think are productive. A couple of weeks ago, over 200 INGOs from more than fifteen countries wrote an open letter to the UN urging them and other international NGOs to work and collaborate with us—including on funding, logistics, and security. We stand ready, willing, and able to do that, despite what the UN says about us. Our mission is to feed people. If you want to do the same, we’re willing to work with you.

PP: That’s so interesting, because I hadn’t heard of that. It doesn’t seem to have made it into the media. But I had heard there were lots of complaints from other organisations. Not specific to working with you—because they weren’t working with you—but a sort of petition to kick you out.

CF: I don’t want to get into the motivations of so-called humanitarians. You’ll have to ask them. But I will say: take out the politics, the corruption, and the failure of the legacy system, and what GHF is doing is a new way of operating. We’re a disruptor in a decades-old, if not century-old, industry. Change is hard. And, to quote a movie, the first people through the wall always get bloody. I think that’s what’s happening.

The government of Israel notoriously kicked UNRWA out of the region. Not sure they’ll ever return. But the other UN organisations are allowed to operate. We hope to work with them.

I don’t have a good answer as to why GHF is so highly criticised and vilified, other than our model is working. We’ve put over 170 million meals directly into the hands of tens of thousands of people.

PP: And who is that a problem for?

CF: Well, it’s a problem for Hamas, for sure. As I said, they made it a negotiation point. During ceasefire talks six or eight weeks ago, one of Hamas’s sticking points was that GHF had to leave.

Another interesting point: you mentioned that period when the UN and other NGOs were inside Gaza but not distributing their aid. I’ve said we’ve had zero diversion. During that same period, the Washington Post published an article about how Hamas’s finances were being decimated. They were having trouble waging war and recruiting fighters. That happened while GHF was distributing and the UN was not.

The Washington Post didn’t connect the dots, but I will. It’s not a coincidence that you can’t steal GHF aid, and the UN wasn’t delivering theirs, and Hamas was having trouble with its finances. That’s not a coincidence.

Our model is working. We believe we can help the United Nations solve that problem. We also believe they can help us. As I said, they have an unlimited supply of aid in various forms, and we have a system that is delivering aid daily to southern and central Gaza. Hopefully, we’ll be able to reach the north soon.

We push the IDF to secure that area so we can expand and deliver food. You’d have to ask others about their motivations. GHF doesn’t care. We’re willing to work with anyone—including the United Nations and leadership that’s been highly critical and, I think, disingenuous.

But no matter. We are happy to collaborate, and we are hopeful and optimistic that one day soon, that will happen. And again, imagine how many people we could feed if we worked together.

PP: Well, thank you very much. And I wish you luck. It’s important work.

CF: Thanks. Appreciate the time.