AI

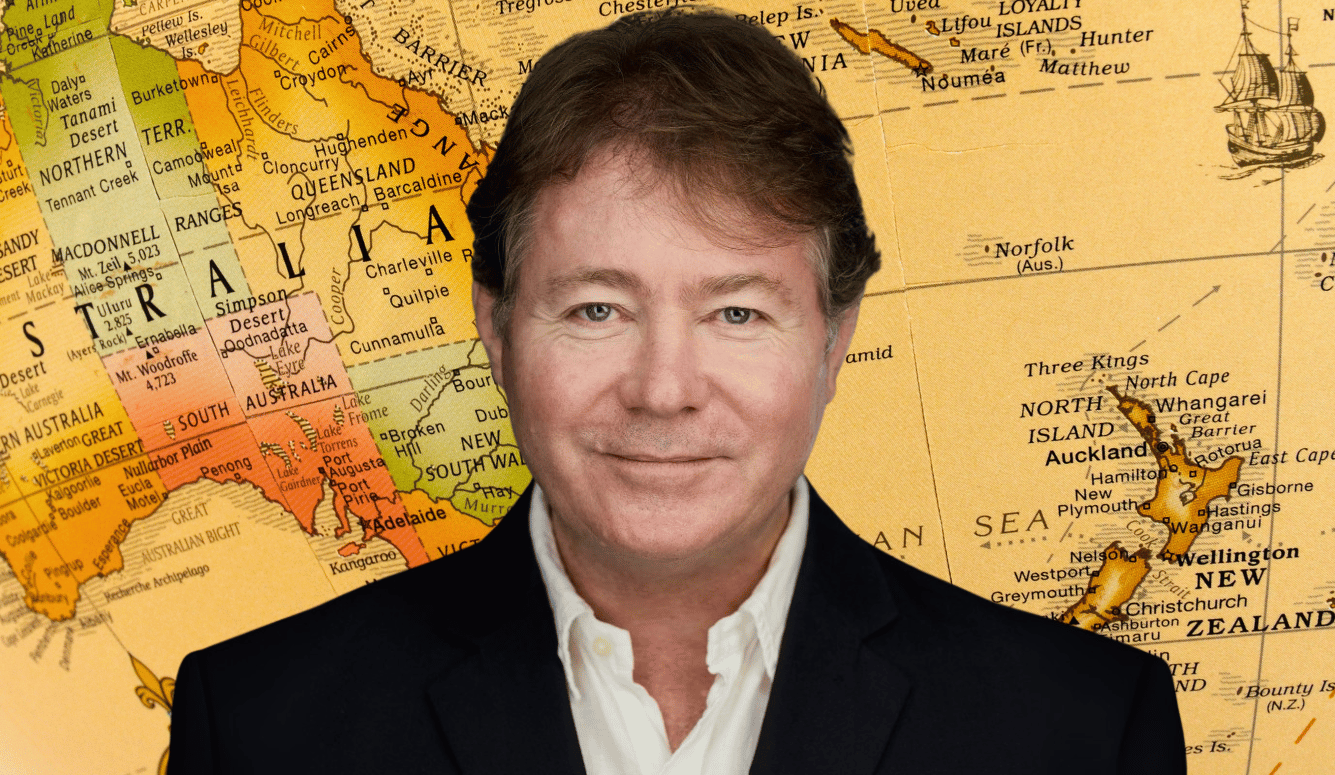

Robot Ethics and Colonial Legacies with Sean Welsh | Quillette Cetera Ep. 53

Philosopher and programmer Sean Welsh talks with Zoe Booth about AI, colonial history, and why scepticism is the best guide through both technology and politics.

Sean Welsh is one of Quillette’s most wide-ranging contributors, having written on subjects as varied as artificial intelligence, Middle Eastern politics, and colonial history. Trained in philosophy and employed as a computer programmer, Welsh describes writing as a pursuit of curiosity rather than a career—a way to explore the questions that interest him.

In this conversation, he speaks with Zoe Booth about the breadth of his intellectual interests: from the ethics of robotics and the economic realities of AI, to the contrasting colonial experiences of Australia and New Zealand. Their discussion ranges across history—including the Napoleonic Wars and the rise of British naval power—and into contemporary debates about automation, political institutions, and the contested legacies of indigenous relations. Along the way, Welsh reflects on the dangers of certainty, the value of scepticism, and why he remains an optimist about technology’s role in shaping the future.

Transcript

Editor’s Note: This conversation was recorded on 4 July and the transcript has been edited for clarity and readability.

ZB: You write about so many topics. I think you’ve written 21 pieces for Quillette, is that right? From AI to the new leader of Syria to colonial history—everything.

SW: Yes, something like that. I’m a curious fellow. I guess I have broad interests in that respect. History, politics, economics, and technology cover the ambit, which is a fairly broad sweep.

ZB: It’s incredible that you have the ability to write in detail about so many different topics. I’m not here to boost your ego, but it’s quite incredible. What would you say your expertise is? AI and robotics?

SW: Thank you. My PhD was in the area of Asimov’s laws, which is the easy way to explain it. It was about how to get robots to make moral decisions. I decided to do robot ethics for my PhD because I worked as a computer programmer. I was a self-taught guy with a philosophy degree, and I had that moment like the character in the musical Avenue Q: “What do I do with a degree in philosophy?”

I ended up teaching English for a while, then running a backpackers’ hostel, and I worked as an advisor for a politician. Eventually, I fell into computer programming, which is basically just logic—one of the useful things you study in philosophy, apart from marshalling an argument. I fell into web development in 1995, so thirty years ago, and I’ve been earning my living programming ever since. It’s my day job.

ZB: For any specific type of software?

SW: At the moment, it’s aged care and disability payroll using the SCHADS Award, which is amazingly complicated. I think flying rockets to the moon is easier than understanding the SCHADS Award. It has a lot of conditions and clauses, so overtime calculations can be quite byzantine and bureaucratic. I write software as a common-or-garden computer programmer, basically doing websites, web applications, databases, and data analytics. That’s my day job, and writing is a hobby. I’ve always had a desire to write a book and I’ve actually written two, so I got that out of my system. Now I just dabble when I feel like bashing out 3,000 words for Quillette.

ZB: You must read a lot. I just read your book review of Empire and the Making of Native Title by Baine Attwood. It’s very interesting. I’ve always wondered why Australia and New Zealand seem so similar on the surface but have quite distinct histories when it comes to colonisation and relations with our indigenous peoples. And I get the feeling that you’re both Kiwi and Aussie, is that right?

SW: Well, I did my PhD in New Zealand, so I sometimes pick up the twang, usually when I’m talking about New Zealand things. I spent nine years there and did my PhD at the University of Canterbury. I went to Canterbury because I followed my wife, who got a job as the earthquake recovery and reconstruction lead for the university after the earthquake. While I was there, I worked as a programmer for a while, but then I decided to do a PhD because she was earning lots of money and I had the opportunity.

That area is home to the Ngāi Tahu, who were one of the first peoples to reach a settlement under the Waitangi Tribunal arrangements. Because of the Treaty of Waitangi, there’s a constitutional mechanism in place that sets up relations between the iwi and the Crown. This never really happened in Australia for various reasons that Baine Attwood explains in his book—basically, who would you do a deal with?

ZB: When you say iwi, is that I-W-I? So it refers to a tribe, and there are multiple iwi?

SW: Yes, an iwi is a tribe. In the South Island, Ngāi Tahu is the big one, but you have many more up north because the population density increases as you get closer to the tropics. One of the interesting things is how many ways the British tried to avoid grabbing New Zealand after saying, “No, we don’t want to colonise you, go away. We’ve got our hands full with New Holland.” They were actually pushing back on further expansion because of the politics in London, depending on which government was in and what the budget position was. After the Napoleonic Wars, Britain was broke and didn’t want to colonise New Zealand.

ZB: And I read that the French were considering colonising New Zealand as well.

SW: Yes. French colonisation often worked with companies—a strange mixture of state-sponsored capitalist merchant adventure firms, like the British East India Company or the Dutch VOC. After losing the Napoleonic and Seven Years’ Wars, the French were on the back foot, scrounging for scraps, and decided they’d sniff around the South Island of New Zealand. There’s a place just south of Christchurch called Akaroa, which today has a very French schtick because a few French settlers actually got there and started farming on land they had bought off the local Ngāi Tahu iwi. They had actually done a deal, which gets to something that happened on the New Zealand side that didn’t really happen in Australia in those first fifty years.

ZB: You also mentioned that the Polynesian translator on Captain Cook’s voyage, Tupaia, could converse with the Māori but not with the Aboriginal Australians.

SW: Yes. When you go to New Zealand, you might hear a mihi, which is an introduction where you talk about your mountain, your river, and your canoe. These are the landmarks of an ocean-going, canoe-travelling people. The Māori have fantastic oceanic canoes that can sail across the Pacific. The languages from Hawaii to New Zealand are all related, kind of like French and Spanish—mutually intelligible to a degree. Tupaia, who was Tahitian, could make himself understood with the Māori. In Australia, by contrast, things were very different.

ZB: It is so different. Unfortunately, we had to take down a very good interview with Mungo MacCallum because it touched on tribal knowledge that some people found very offensive, for example, male initiation rites and the division of labour between men and women. There was such an influx of nasty, threatening comments that we took it down.

SW: I do like Mungo, but there’s a reason he goes by a pseudonym. You just can’t say these things, even though they’re on the record in anthropology and archaeology. There are facts in the ground that say things about indigenous culture that don’t fit the rosy narrative of peace and love. It was often a nasty, brutish world of tribal warfare, like most parts of the world at that time. On the other hand, it was relatively peaceful because the population was very dispersed and had a low density. Most of your day was just trying to forage for a feed because the technology was at such a low base.

You have the Dark Emu chap, Bruce Pascoe. His latest book is a tale of lament about how he was metaphorically beaten up for writing Dark Emu. He made a lot of claims that were contrary to what more established scholars had found and published in learned journals for years. If you put your neck out and stretch the evidence, which he did, you can expect pushback. There’s a comprehensive book by Sutton and Walsh, Farmers or Foragers? The Dark Emu Debate, which demolishes it line by line.

ZB: And yet, Bruce Pascoe is celebrated by these institutions and invited to speaking events and on TV, even though there’s not much scholarly backing for what he says.

SW: To be candid, the scholarliness isn’t really there. It seems that if you are politically in the right place, people will give you a pass. Whereas if you’re more of a classical liberal who asks, “What evidence do you have for this proposition? What’s the counter-argument?” and you weigh them up to find the better view on the balance of evidence, you’re seen differently. You need a Popper-like willingness to have falsifiable beliefs, because that’s what science does. It asks, “Can I disprove your theory?”

ZB: Do you know much about what’s happening in New Zealand at the moment? I see a lot of protests in their parliament about Māori.

SW: This is to do with the minority partner in the ruling coalition, the ACT party, which is a libertarian, right-wing party. Its leader, David Seymour, gained seats by bitterly opposing the COVID lockdowns. Most people give Jacinda Ardern credit for handling COVID well. The situation with ICU wards in New Zealand is not as good as here; they have far fewer. There just weren’t going to be enough ICU beds to deal with a Melbourne-style scenario. People would have died like flies. New Zealand has a moat and is so isolated that she could pull up the drawbridge, which she did on medical advice from very smart people.

ZB: So you think she was a good leader during that time?

SW: I think she did well, though I think anybody would have followed the medical advice. She and Chris Hipkins did a good job of selling the policy. The ACT party represented the twenty percent who thought the measures were too much, but polling always showed sixty percent thought it was just right and twenty percent thought it wasn’t enough. They estimate 30,000 lives were saved. Speaking for myself, living in Christchurch at that time, I was the designated shopper. We had toilet paper, but we ran out of yeast so I could bake sourdough like everyone else. I was doing a PhD, so it wasn’t as if I needed to go to the office.

ZB: People will say you’re part of the “laptop class” who could just work from home.

SW: Guilty as charged. Soon, they’ll be delivering our drinks at music festivals with drones.

ZB: I’ve thought about that. It’s probably already happening. But then there will be an issue with pollution of the sky and things buzzing around.

SW: Who pays when the drone falls down? That’s the main problem. They’d have to fly over roads at a certain height and land on your balcony or porch. That whole Jetsons world isn’t that far away, but robotics always lags behind AI because common sense is just much harder for computers. As Yann LeCun says, cats can figure out the world, but computers are hopeless. A state-of-the-art robot costing $250,000 took 45 minutes to fold a basket of laundry. It’s that common-sense, practical knowledge that’s hard to encode. Computers suck at what humans can do effortlessly.

ZB: I’ve heard concerns that AI can do a lot of what a more junior person can, threatening their career prospects. But it sounds like you’re saying it can do what the really high-skilled people can do, but not necessarily what lower-skilled people can.

SW: Right. My first job was cutting up chicken at Coles, then I was a short-order cook. I moved up to unloading trucks and eventually got promoted to the shop floor serving customers, which was so boring I asked to go back to the warehouse. That kind of job might be an exception because warehouses have been highly robotised by Amazon. But you still see humans doing a lot of things in supermarkets. For example, at my local Coles, there’s always a teenager pushing a trolley, picking items off the shelf for a pickup order.

There will be new jobs to replace the ones that die. People have been making arguments about mass technological unemployment since the Luddites. I think the new jobs will outnumber the old jobs, but whether they have the same status or prestige, who knows. People often say computer programmers are doomed, but I’ve never been starving for projects. It’s always been a matter of projects being too long or expensive. As the cost comes down, more people will want custom software because they’ll get dissatisfied with off-the-shelf products. It’s like tailoring. When tailoring is cheap, everyone wants custom-made clothes. The same will happen with software. I can write more software in a day now than what used to take me a week. There is no shortage of software problems, I can tell you.

ZB: Do you think you’re working less? I find that even though I can do tasks much faster with AI, I just end up doing more of those tasks.

SW: The stuff I do now is more interesting. I used to get stuck for days on mundane problems. Now I can ask ChatGPT something quite complex code-wise and it will give me an answer. It might not be correct, but it gives me a starting point. It does tend to hallucinate, so I tend to ask it things I already have some knowledge of—more to remind me than to tell me. The danger is that people might grow up with a “smartphone knows everything” mentality and nothing is ever stored upstairs. But this is an old argument. Socrates made the same argument about writing, saying if youth learn to write, they’ll never learn to remember anything. He argued passionately that writing would rot your brain. Those arguments could be transposed word-for-word to the iPhone generation.

ZB: Can we talk about AI alignment?

SW: I love that question. The first thing to ask is: With which human values are we to align the AI, Zoe? Shall we align with your values?. The obvious question is, whose values? People have been arguing about values for the entire history of philosophy. I generally sidestep all that and say, forget abstract values for a moment; just comply with the law. Comply with the laws of New Zealand if you’re in New Zealand, or the laws of Australia if you’re in Australia. That approach at least has the advantage of being predefined. GPT-3.5 passed the bar exam two years ago, so understanding the law is not beyond the wit of AI.

The whole alignment debate is often just window dressing for an ideological argument about whether you should be individualist or collectivist, progressive or conservative. I found that in terms of its ideology, ChatGPT is like a California Democrat. I can do business with a California Democrat. On most of the basic stuff—should there be sewage in the streets?—the middle-of-the-road, nuts-and-bolts politics is not that different. It’s the attention-grabbing froth that gets the clickbait.

ZB: Speaking of politics, do you have any strong opinions on Australia becoming a republic?

SW: I am actually cautious about it. I voted “No” in the 1999 referendum. I like constitutional monarchy because it works, and it works because it has a fusion of parliamentary supremacy with a monarch who is above politics. The main republican models are America and France, with their division of powers. Frankly, I think Donald Trump is the best argument for constitutional monarchy in a hundred years. You look at the most advanced republic in the world, and it looks like it’s heading towards Burkina Faso in its politics.

In a good system, the head of state is separate from the head of government. That’s an important separation. In all the republics that go to pot, from African dictators to Saddam Hussein, the head of state and head of government are the same person. When the executive can intimidate the legislature and judiciary, you run the risk of a megalomaniac taking over. Having that monarchical tradition, so long as it stays above politics, is a safeguard. The Crown is the dignified part of the constitution, as Walter Bagehot wrote in 1867. You get the unmatched razzmatazz, the ceremonial aspects, the royal weddings that get audiences of billions. Why would you say goodbye to all that?

ZB: And so why won’t a treaty work in Australia?

SW: I wouldn’t say it’s an impossibility, but there are difficulties. Māori is one language, intelligible from the north of New Zealand all the way to the south. There’s a unity and a standard Māori that’s taught across the country. That cannot be replicated here. In Australia, most Aboriginal languages have very small numbers of speakers because of the highly dispersed nature of the society. Governor Hunter, the second governor, said that people living fifty miles from each other had different words for the sun and the moon. So the difficulty with a treaty is that it would have to be a treaty with each of these distinct groups. These things have to be done at a local level.

ZB: It does seem that race relations in New Zealand are just a lot better than they are here.

SW: The main thing about the Māori is they’re damned good football players. They are hugely overrepresented in the All Blacks. And the whole haka thing—the Māori war dance—is something that every school kid in New Zealand learns. White kids too. You see Kiwis break out into a haka for any excuse: a funeral, a wedding, a christening. There’s an acceptance of Māori culture, what they call biculturality, that comes from the treaty. It’s more inclusive. It’s perfectly okay if you’re a white person to speak Māori. I remember one of my favourites was a Muslim girl from Iraq who did her mihi. For her mountain and river she named ones from her homeland, and for her canoe, she said, “Emirates Te Waka”—my canoe is Emirates. It went viral. That’s how she got there.

ZB: After getting to know more about Jewish history, I’ve thought about this idea of dispossession. Jewish people have been persecuted, dispossessed, and murdered for centuries, yet they don’t suffer from the same negative metrics that other groups do.

SW: I totally agree with you. Thomas Sowell is right; it’s primarily cultural. Race is overdone as an explanation. The issue is the culture. If you see yourself as a victim, you will be a victim forever. You’ve got to move beyond it and get on with stuff. That’s something the Jewish community, being perpetual refugees, has done. They’ve been scattered to the four corners of the Earth, subject to pogroms and the Holocaust, and yet they have this narrative of education, hard work, and survival. I once ran a backpackers in Cairns and a young religious Jewish man asked for the synagogue. I looked in the Yellow Pages and there wasn’t one. I rang a Jewish friend who said, “You schmuck, there’s no synagogue in Cairns. We dial a rabbi from Bondi or St Kilda!” That highlights a certain practicality. You see it with other migrant groups too, like the Chinese or the Greeks, who found a niche and thrived through hard work.

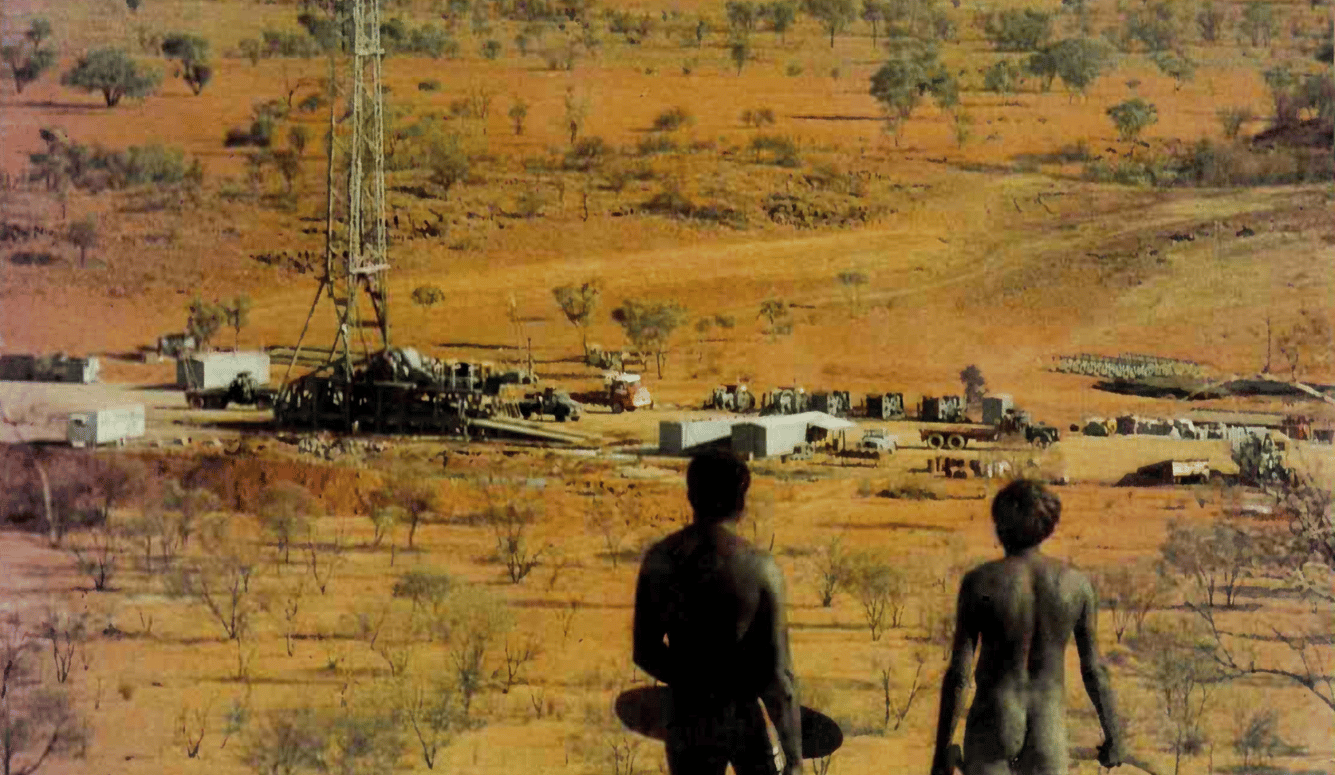

ZB: To wrap up, you coined the term “Malthusian swamping” to describe the demographic and technological overwhelm of indigenous people by settlers. How does this differ from traditional narratives of conquest?

SW: It’s a halfway house between the “black armband” view of history, which says every square metre of Australia was won through bloodshed, and the “white blindfold” view that says nothing happened. The documented reality is that while bloodshed was common, it was usually sporadic and at the level of a skirmish, not a full-scale war like Waterloo where tens of thousands died in a day.

There was a baseline of resistance, as Aboriginal groups would throw spears in response to incursions on their food sources. The white settlers would retaliate, often killing ten to one. But the ones who survived were then simply swamped. There were just so many white people coming, boat after boat, at a rate of population increase that the Aboriginals couldn’t keep up with. The men had often been killed, so the women had to marry white men, leading to a mixed-race population and a gradual dilution. This was compounded by the fact that the English population was expanding exponentially due to advances in agriculture, creating massive migration out of Europe where there wasn’t enough land. To call it just a racist conquest is glib. It doesn’t look at the economic and biological logistics, which to me is a far more substantial thesis.

ZB: Thank you so much for joining me, Sean, for this very varied conversation.

SW: My pleasure. Thanks very much .