Nations of Canada

Godly Missionaries—or Evil Sorcerers?

In the 27th instalment of ‘Nations of Canada,’ Greg Koabel describes the epidemics that ravaged Wendat communities in the 1630s, sparking suspicions that Jesuit preachers were practising deadly witchcraft.

What follows is the twenty-seventh instalment of The Nations of Canada, a serialised Quillette project adapted from Greg Koabel’s ongoing podcast of the same name.

In the summer of 1634, two French Jesuits—Jean de Brébeuf and Antoine Daniel—arrived in Huronia (also known as Wendake), the homeland of the Wendat Confederacy. It’s an area roughly centred on the land between Georgian Bay and Lake Simcoe in modern Ontario. These days, it serves as cottage country for residents of Toronto. But four centuries ago, it lay at the centre of eastern Canada’s most important Indigenous trading network.

For Brébeuf, a skilled linguist eager to master the Wendat tongue, this was a long-awaited return. Eight years earlier, he’d established the first Jesuit mission among the Wendat, but then was forced to abandon the project when Quebec was (temporarily) conquered by English invaders, as discussed in our 24th instalment.

A subsequent Anglo-French peace deal allowed the Jesuits to return to Canada in 1633, but a diplomatic dispute delayed matters. After a year of fruitless negotiation, Brébeuf and Daniel grew tired of waiting in Quebec (modern Quebec City) and paid a group of Wendat traders to smuggle them into their homeland. This act of rogue diplomacy went a long way toward restoring the old “Laurentian Coalition” (first discussed in instalment number sixteen), which bound the French to not only the Wendat (whom the French called Huron) but also their Algonquin allies, who inhabited the Ottawa River basin and supplied much of the fur purchased by French traders.

For the next fifteen years, Brébeuf would remain a prominent force in Wendat politics and society—a linchpin of commercial and diplomatic relations between the Council of the Wendat Confederacy and the French colonial authorities in Quebec. But Brébeuf’s real mission transcended such earthly concerns. He was there to save souls and re-shape Wendat society according to a Christian template.

In so doing, alas, he and his colleagues would unwittingly sow the seeds of the Confederacy’s downfall.

In part, this is because the Jesuits unknowingly brought with them infectious pathogens that were new to this part of the world. What’s worse, a new batch of microbes arrived annually with each supply run from France.

Over the years, historians have debated the nature of the disease that ravaged Huronia during this period, with some identifying it as smallpox, others measles. More modern researchers tend to suspect it was a form of influenza. Whatever it was, by July 1634, it had spread to Trois-Rivières, the then-newly established settlement upriver from Quebec, where much of the St. Lawrence fur trade played out. From there, Wendat traders (including those who ferried the Jesuits) brought the disease back to their villages.

The 1634 epidemic wasn’t entirely unprecedented. It’s possible that Jacques Cartier brought some kind of European disease to the St. Lawrence River a century earlier, though there’s little evidence that it spread widely. And there was a European-spawned epidemic of some kind that ripped through New England in the 1610s, clearing the way for English settlement in the following decades. But this was the first large-scale epidemic north of the St. Lawrence and Great Lakes that affected a wide swathe of societies.

Archaeological evidence suggests that population levels in the region had remained more or less consistent since the Indigenous population explosion caused by the advent of corn cultivation in the fifteenth century (which we learned about way back in our third instalment). Then, in the mid-1630s, they dropped precipitously.

Nor would this be the last such cataclysm. Although nobody knew it at the time, Canada was entering a century-long period during which epidemics became a persistent and devastating fact of life.

Although it didn’t seem like it at the time, that first 1634 wave of disease represented a rather mild form of influenza—far less deadly than those that would follow. Although the infection rate was high, the fatality rate was relatively low. Most of those who caught the disease eventually recovered. There’s little indication that Wendat society treated the epidemic as an existential threat. Nevertheless, there were still serious economic consequences, as much of the Wendat work force was incapacitated. The corn harvest suffered, as many women were too ill to tend to the fields, and there were multiple reports of crops being left to rot.

Initially, Brébeuf ignored the spreading disease and focused on his mission to learn everything he could about the Iroquoian languages spoken by the Wendat. He’d already learned all he could from the notes and manuscripts left by the old Récollets missionaries whom the Jesuits had displaced, and so devoted himself to the hands-on work of engaging his hosts in conversation.

Through such methods, Brébeuf didn’t just learn the language, but also the nuances of Wendat politics that had so far eluded other French observers. Upon their arrival in Huronia, for instance, Brébeuf and Daniel learned that the Wendat were in the process of relocating their largest village, Ossossone, as part of the cyclical generational process necessitated by soil depletion. The new site, located just north of the modern Georgian Bay vacation town of Wasaga Beach, would be completed the following summer. In the meantime, the Wendat offered to host the Jesuits at Ihonatiria, a village in the northern portion of Huronia.

Through his talks, Brébeuf learned that Ihonatiria had been the home of French translator Étienne Brûlé until his murder in 1633 (an event described in our 26th instalment). Since then, the village had split in two, with some residents constructing a new village nearby, named Wenrio. These residents hoped to distance themselves from Brûlé’s killers, in order to avoid feared French reprisals. Despite reassurances provided by Samuel de Champlain, the longtime French colonial leader, anxiety about how the French would respond to the killing still divided Wendat society.

That cleavage persisted for some time, and played a role in how some Wendat interpreted French behaviour in subsequent years. Were the Europeans just feigning indifference, and waiting for an opportunity to exact revenge?

Sensing that this could develop into a problem, Brébeuf did his best to reaffirm Champlain’s sanguine position on Franco-Wendat relations. He urged the two villages to reunite, arguing that the divisions underlying the split were groundless. These earnest efforts proved fruitless, however: Brébeuf was politely informed that the act of splitting the villages had been hard work, and there was little appetite to undertake another similarly complex social engineering project any time soon.

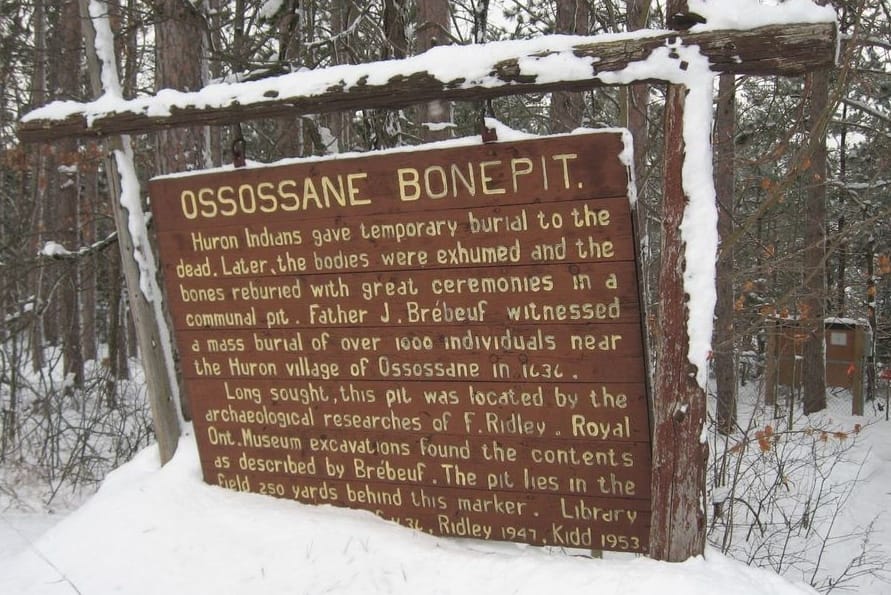

As Ossossone prepared to migrate to its new home, a Feast of the Dead was held to commemorate the old village. This was a highlight of the Iroquoian cultural calendar, as all of those who’d died during the life of the old village were exhumed and buried in a common ossuary. (The Ossossone ossuary was rediscovered in 1946, and was found to have contained the remains of more than 600 individuals.)

While the Feast of the Dead originated before the arrival of the Europeans, it was a living tradition that was adapted to contemporary circumstances. And Brébeuf worried that he was witnessing an adaption that did not bode well for stability within the Wendat world.

Brébeuf no doubt had an imperfect and distorted understanding of Wendat politics and history. Nevertheless, he was convinced that this particular Feast of the Dead had novel characteristics. It wasn’t just the residents of the village who were being ceremonially placed in the ossuary. A general call went out to the entire Attignawantan people—which is to say, the Bear Tribe, which accounted for about half of the Wendat population—to assemble and bring the remains of notable figures from their own villages to bury in the ossuary as well. According to Brébeuf, this kind of consolidation was a fresh innovation.

Brébeuf’s hosts at Ihonatiria, who belonged to the smaller Arendarhonon tribe (also known as the Rock Tribe), paid close attention to these developments. Word spread that residents of Arendarhonon villages in northern Huronia would now be incorporating tribal group identity into their own Feast of the Dead ceremonies.

Brébeuf feared the emergence of rival blocs within the Wendat Confederacy, which would undermine its unity and strength. Moreover, he suspected that these emerging divisions were partly based on attitudes toward the French.

As readers may remember, the Wendat Confederacy had originally arrived at a compromise in regard to their management of the French relationship. The smaller Arendarhonon had been the first to establish a link with Champlain and his men; and therefore, by custom, retained a special relationship with the Europeans. But the importance of the French alliance was such that the largest nation of the Confederacy, the Attignawantan, couldn’t be excluded from French affairs without disrupting Wendat politics. So the Wendat council decided to manage the alliance at the national level, while also allowing the Arendarhonon to be seen as retaining a special relationship with the French.

Brébeuf worried that the divisions that seemed to be emerging in late 1634 resulted from that longstanding compromise arrangement becoming strained. The northern Arendarhonon villages were on the periphery of the Confederacy, with power concentrated among the Attignawantan to the west. But now, the north was hosting the Jesuits. Would that special relationship give the Arendarhonon an outsized share of power, by means of privileged access to French trade goods and diplomatic connections?

Once again, there was probably more going on than Brébeuf grasped. But the presence of the French certainly had at least some significant effects on Wendat politics. And part of Brébeuf’s job was to manage these new fault lines.

Whenever possible, however, Brébeuf returned his focus to what he considered to be his primary job—saving souls. That first winter, when he spread the Christian gospel to the inhabitants of Ihonatiria, some of Brébeuf’s methods were cynical. He doled out tobacco to encourage people to attend his preaching sessions. He also gave out prizes to children who could demonstrate that they’d memorised the catechism.

But Brébeuf didn’t delude himself that these were signs of real progress. He was just engaging in a bit of showmanship to get the ball rolling. Like most other Jesuits, he abhorred superficial conversions that did little to bring souls closer to God. In the early days of French Acadia, the secular leaders of the colony had tried to prove they didn’t need spiritual oversight from Jesuit missionaries by quickly performing a large number of shotgun baptisms. Brébeuf was determined to take a more rigorous approach: Baptisms would take place only after candidates had been thoroughly vetted, to make sure they understood the meaning of the conversion rituals.

Even when the Wendat expressed enthusiasm for his lessons, Brébeuf typically reacted cautiously. He noticed that during his sermons, traders and political leaders were the most attentive listeners. Brébeuf suspected that they were motivated by material concerns. It did not escape notice, for instance, that when Brébeuf’s most diligent student in Ihonatiria, a man named Tsiouendaentha, travelled to the St. Lawrence, he received preferential treatment as a Christian, receiving more lavish gifts from the French than his colleagues.

Many of these men derived their status within the Confederacy from their close relationship with the French. Their ability to distribute European goods among their neighbours afforded them heightened influence. Were they really interested in Christianity? Or did they merely see acceptance of the French God as a useful public symbol of their political connections?

Brébeuf was frustrated to find that while many audience members listened attentively to the word of God, they continued going about their pagan practices after his lectures. And so what looked like easy victories were, in fact, just mirages. Such frustrations seemed to confirm the lessons he’d learned during his Jesuit training back at Collège de La Flèche in France: missionary success would come, if at all, only after hard work and many setbacks.

For now, Brébeuf focused on teaching the word of God, rather than ministering to his hosts as if they’d truly become Christians. The one exception he made was to baptise Wendat men, women, and children if they appeared near death. For Brébeuf, this was a humane concession. Baptising a man, only to have him continue living a traditional Indigenous life, would make a mockery of the sacrament. But as a final preparation for the afterlife, baptising someone with a less than complete understanding of what it meant to be Christian was an act of charity.

This practice of baptising those near death (which other Jesuits took up after Brébeuf) had unintended consequences, however.

From the Wendat perspective, this was a powerful ritual, one that lay at the heart of European spirituality. Even if they didn’t fully understand what baptism signified, they were convinced that it was somehow associated with death—as the Jesuits were performing these rites only on those who were gravely ill.

What’s more, the arrival of the Jesuits and their death rituals coincided with several waves of disease, cataclysms with no precedent in the Great Lakes region within living memory. Were the two connected?

Lingering doubts surrounding the sincerity of French friendship compounded the problem. Were they allies? Or were they only posing as friends while they plotted their revenge for the murder of Brûlé?

In order to unpack how the Wendat understood these baptisms, and their relationship to the spread of disease, we’re going to have to examine Indigenous understandings of health during this period.

Historians break seventeenth-century Indigenous healthcare into three broad categories. The first was what one might call conventional medicine (by the standards of the era). If you were suffering from an illness, you would likely turn to a respected man or woman within your community for a natural remedy to restore your health. You might also get some advice on diet or perhaps a physical treatment such as the use of a sweat lodge. Although the specific methods may have been unfamiliar to European observers, the basic structure was comprehensible: Local neighbourhood apothecaries and other medical practitioners provided roughly analogous services back in France.

However, if your poor health continued, you might turn to options that would have seemed quite alien to a Frenchman.

A second type of Indigenous healthcare could be (anachronistically) described as psychological. In the Wendat world, some physical ailments were seen as the product of an unfulfilled desire of the soul. This desire was often subconscious. In other words, the sufferer did not know what it was that their soul desired.

Dreams were the primary conduit through which such unfulfilled desires were identified, usually with the aid of an elder to interpret their meaning. Quite often, the desire was for a material object, which might then be provided by the community.

In addition to shedding light on how Indigenous societies understood health—in particular, the connection between mental and physical well-being—such practices highlighted the contrast between economic principles in the European and Indigenous worlds. Among the Wendat, social practices (such as the exchange of goods) were usually designed to promote harmony in the community (or, in the case of ritualised gifting, between different communities). If a member of the community truly required a knife or a copper kettle in order to restore his or her spirits, neighbours might oblige.

In most Indigenous cultures, one’s needs often were taken as primary considerations, not the intrinsic value of the underlying goods. Friendship (whether on the individual or national level) meant providing gifts when your friend was in need. Reciprocity need not be immediate, but could come in the future when you were the one in need due to the ups and downs of the hunt or harvest.

This concept baffled Europeans when applied to commerce, and the resulting misunderstandings would periodically complicate intercultural trade. Indigenous groups often emphasised their poverty or desperation in an attempt to convince European partners to offer more favourable terms of exchange. This did not usually have the desired effect on capitalist-minded Frenchmen. (In a purely capitalist context, in fact, such an appeal might be expected to have the opposite effect, as it signals to the opposing party that he can dictate the terms of trade.)

More relevant to our current story is a third type of Indigenous health-care paradigm—which, for lack of a better term, I’ll refer to as witchcraft.

Some illnesses, it was believed, were the product of malice. Particularly wise and knowledgeable men had access to the spiritual world, affording them impressive powers. These powers were, in and of themselves, morally neutral—neither good nor evil, much in the way that fire can be used to cook a meal, heat a home… or burn down a village. The individual had the ability to use these powers for either purpose. A gifted spiritualist could perform rituals that granted success in war or the hunt—or inflict harm on others, including through illness.

There were two main motivations believed to be at play when such powers were used in a malevolent fashion. The first was jealousy. Again, this played into the tendency of Indigenous social technologies to promote community harmony. Jealousy was seen as a combustible phenomenon, whose manifestations had to be carefully managed. (This explains why generosity was celebrated within the Indigenous cultures that the Jesuits encountered: One way to avoid being the target of jealous witchcraft was to share one’s wealth as widely as possible.)

The second suspected motivation for the evil use of spiritual power was revenge—also a highly destabilising force in Iroquoian society (or, indeed, any society). Wendat social and political institutions (particularly the Confederacy) were designed to eliminate feuds before they became violent and destabilising.

No matter what motivated witchcraft, it was believed that there was only one cure for those targeted by an attack: The curse must be broken by the confession of the assailant—usually under torture. (In this unfortunate respect, Indigenous and European societies were not so different, as sporadic witch hunts had been part of Christian life all over Europe from the fifteenth century onward.)

At this point, readers can presumably see where all this is heading: The Jesuits’ Wendat hosts observed that a mysterious force was striking down their people at an alarming rate. Neither conventional medicine nor the fulfilment of unrecognised desires did anything to alleviate the epidemics. At roughly the same time, two Jesuits had arrived in Huronia—men who directed their most powerful ritual at those who’d been struck down grievously by the mysterious illness. They staunchly refused to perform their baptisms on anyone in good health, even their closest friends among the Wendat. Given all this, it should not be surprising that some Wendat theorised the French priests were using occult powers to secretly prosecute a blood feud arising from Étienne Brûlé’s death.

It’s important to note, however, that—at this point, at least—few people assumed the worst. The French relationship had been a boon to Wendat society for over twenty years, and there were good reasons to trust French assurances that Brûlé’s death hadn’t cast a permanent cloud over the relationship.

And yet the priests gave strange-seeming explanations for their actions. For Wendat observers, baptism would have been most comprehensible as a curing ritual. Yet Brébeuf himself explicitly informed everyone that curing people was not his intention—at least, not in any physical sense. Even when baptised individuals recovered from their illness, Brébeuf did not take credit, but simply attributed their recovery to God’s favour.

Brébeuf explained that baptism was an important step in securing salvation in the next life. The Wendat were familiar with the concept of the afterlife in general terms. (The communal ossuaries created during the Feast of the Dead were designed to ensure that the community stayed together after death, as they embarked on a celestial journey to the west.) But the afterlife Brébeuf was talking about was very different. For one thing, he and the other Jesuits seemed anxious to get there, describing it as a superior form of existence.

If heaven was so great, what was everyone waiting for? Why not go there now? And was this what baptism was really about—a way to speed people to that heavenly firmament that the Jesuits themselves couldn’t wait to get to?

The carefully guarded celibacy of the Jesuits also elicited awkward questions. Most other Frenchmen who came into contact with the Wendat, either as traders or interpreters, weren’t shy about forming sexual relationships with Indigenous women. Such unions were, in fact, encouraged. Sex and marriage were traditional ways of forging trade relationships with outsiders, as kinship was the primary way men and women were defined in Indigenous societies. Until such bonds were created, foreigners would remain outside of the circle of comprehensible social relations. What did it say about the Jesuits that they were totally okay with that outsider status?

Complicating this analysis further is the fact that within the Iroquoian world, celibacy was seen as tied to spiritual power. Warriors often would refrain from sex in the lead-up to battle, so as to focus their power. Was it possible these Jesuits had learned to channel their extraordinary spiritual powers by adopting a more permanent form of abstinence?

The poor corn harvest in the Fall of 1634 brought formerly unspoken suspicions out into the open. Not only had the influenza epidemic devastated the Wendat workforce, but the late summer and autumn proved abnormally dry, further weakening the crops, and causing at least two villages to be badly damaged by fire. One elder blamed the Jesuits for the drought, claiming that the cross they’d erected outside their cabin was exerting an evil influence.

Brébeuf managed to calm tensions by convincing the community that the Christian God was their protector. He organised a procession, after which the rains came—proving (to some, at least) the good intentions of God and his Jesuit intermediaries. This display wasn’t exactly theologically sound, as Brébeuf risked giving the impression that his God was merely some kind of local weather deity who existed within a larger polytheistic pantheon, but he took whatever goodwill he could get.

By Spring 1635, things seemed to be looking up. By then, the first wave of illness had passed, and all signs pointed to a strong growing season. Brébeuf recorded the seasonal rhythms of Wendat life. The women planted and tended to the fields, while groups of men periodically ventured out of the village on hunting trips, war parties, or trade voyages to the St. Lawrence.

That year, the returning traders brought with them two more Jesuits, who joined Brébeuf and Daniel in studying the Wendat languages. As their abundant surviving records show, they were methodical in their work, recording conversations with their hosts, then reading back the transcripts to clarify grammatical rules or correct mistakes. These were later compiled into written dictionaries and grammars that could be studied by missionaries-in-training back in Quebec.

The French also provided a degree of security. A handful of French workmen had accompanied the Jesuits to act as support staff. Some were armed with muskets (greatly pleasing the Wendat, who remained wary of Haudenosaunee raiders from the south side of the St. Lawrence). It’s also possible that Wendat engineers picked the brains of their French guests, as there’s evidence that around this time Wendat palisades adopted some European features, such as cornered bastions and ramparts to provide cover for archers.

After a second winter, the Jesuit mission reached an important milestone: In Spring 1636, Brébeuf was invited to speak at a meeting of the Wendat Confederacy Council.

The issue at hand was the great Feast of the Dead that was to mark the above-described relocation of the Confederacy’s largest village, Ossossone. In particular, Council members were unsure of what to do with the remains of those Wendat whom the Jesuits had baptised. The divergent Indigenous and European visions of the afterlife raised a thorny problem.

The whole point of the Feast of the Dead was to ensure that the souls of the dead travelled together in their journey to the Village of Souls, described as being somewhere in the west. But Brébeuf had made it clear that baptised Christians went somewhere else after their deaths.

In fact, this had been a point of concern among the Wendat from the beginning. Some non-believing Wendat had even pleaded with the Jesuits to baptise them simply to ensure that they’d be able to join their baptised family members after death.

The Council was uneasy about the thought of separating the community in the afterlife. The whole point of the Feast of the Dead was to promote unity, not emphasise divisions.

It’s likely that the Council was hoping that Brébeuf might clarify the finer points of baptism, and point them toward some kind of compromise. Alas, the leader of the Jesuit mission may have missed the political delicacy of the situation. And he instead used the platform to remind Wendat leaders of Champlain’s 1634 directive that the full conversion of Wendat society would eventually be a necessary precondition of their alliance. He hoped this speech before the Council was the first step toward a formal policy of Christianisation from the top down.

In his casual assumption that these Wendat leaders could pressure everyone else to adopt Christianity, Brébeuf was channelling the well-established European notion of ius reformandi, by which the faith of a territorial lord determined the faith of his subjects. But of course, as we’ve seen many times over during the course of our story, that kind of rigid hierarchical model didn’t fit Indigenous society.

The Council received Brébeuf’s address diplomatically. That was the custom after all, and it wouldn’t do any good to explicitly contradict a French official representative. But, in the end, they ignored the Jesuit leader, and sought out a compromise of their own. There would be one, unified Feast of the Dead, with both baptised and unbaptised remains reburied together. Perhaps their souls would part ways in the future, but as far as the Wendat Confederacy was concerned, baptism was no reason to discriminate within the community.

Several months later, the Jesuits once again got a chance to exert influence within Wendat politics, this time with more auspicious results. Tessouat, the great Kichespirini chief on the Ottawa River (whom we met in our fourteenth instalment), had recently died. Following a common practice in Indigenous societies, “Tessouat” was both a name and an office, and so a new Tessouat took his place. This created a problem, because the main Wendat trade convoy on the Ottawa River was held up for weeks at the Kichespirini-controlled bottleneck at Morrison Island. The new Tessouat was holding out for a generous gift of condolence for the death of his predecessor. In his opinion, the paltry goods offered by the Wendat traders were insufficient.

The standoff was resolved by the arrival of Antoine Daniel, the Jesuit who’d initially accompanied Brébeuf to Huronia. In filling what would become a familiar role for French representatives, Daniel acted as a third-party mediator, and brokered a deal that satisfied both sides. The much-delayed convoy arrived on the St. Lawrence in August, where the Wendat traders received news that after three decades in Canada, Samuel de Champlain had died. This time, a generous gift of condolence was offered without any prompting.

For the Wendat, it was the end of an era. Brûlé and Champlain, each of whom played crucial roles in forging the Franco-Wendat alliance, were now both gone. The French were now represented by the Jesuits in Huronia, and by a series of royally appointed governors on the St. Lawrence.

When the Wendat traders returned home that fall, they brought with them canoes full of European goods, but also, another European-spawned epidemic. This one proved to be far more fatal than its 1634 predecessor.

The trade network upon which Wendat wealth had been built was now a conduit for infection. The French reported an outbreak in Quebec in August (probably brought by European supply ships). By the fall, it was in the Ottawa River Valley, then Huronia itself, and by winter it had reached Wendat trading partners further afield, such as the Nipissing to the north, and the Ottawa in the western Great Lakes.

Diagnosis across the centuries is difficult, but this infection, too, appears to have been a strain of influenza. The Nipissing, who wintered in Wendat territory, returned to their summer fishing grounds in the spring of 1637 carrying seventy bodies, perhaps ten percent of their group’s total population. The death toll within the Wendat Confederacy was almost certainly greater, and magnified all of the concerns that had marked the epidemic that followed the Jesuits’ arrival in 1634.

As the mysterious deaths continued to pile up, suspicions of the Jesuits grew. Why were they here, anyway? some wondered. They didn’t seem to do much. They weren’t warriors like the French musketmen valued by Wendat strategists, nor were they skilled builders or hunters. They weren’t even great healers, as evidenced by their failure to stop the epidemic. And yet, they clearly carried enormous status within French society.

The Jesuits also seemed to be somewhat aloof—even from their own countrymen. Their tendency to live in their own cabins rather than sharing the hospitality of the longhouse; their refusal to allow anyone into those cabins at certain times; their celibacy; their refusal to participate in certain community rituals… These all pointed to a dangerous form of alienation from the community.

Not only did the Jesuits avoid certain traditional Wendat ritual practices, but they actively denigrated them, and tried to convince their converts to avoid them, too. Sowing discord in this way was simply unheard of in Indigenous societies.

As we’ll see, Huronia would be transforming into a frightening and chaotic place more generally during this period. And there’s evidence that the Wendat were increasingly directing witchcraft accusations not only at the Jesuits, but against other members of Wendat society.

In December 1636, leaders from five of the northern Wendat villages convened a Council and invited Brébeuf to join them. At that meeting, they warned him that accusations of witchcraft were getting harder to suppress. Soon, they may not be able to guarantee the safety of the missionaries.

This wasn’t so much a threat as a good-faith warning. Wendat leaders were in a tight spot themselves. It was clear that the Jesuit presence was an absolutely necessary component of the French alliance. And the French alliance (along with the European trade goods it brought) was seen as a critical means to protect Wendat territory from Haudenosaunee rivals. And yet, popular pressure was making the French presence problematic. What good would it do to protect Wendat society from external threats if it was just going to be torn apart from within?

A complicating problem was that banishing the Jesuits might not only irreparably harm French relations, but also, by extension, the economic system that underpinned the Wendat political elite. Two decades of trade had reshaped Wendat politics, and many powerful men now owed their status to their ability to distribute European goods to their neighbours. How would they react if the French missionaries were sent home?

On the other hand, if someone took matters into his own hands, and harmed one of the Jesuits on a rogue basis, the Wendat would be facing a far greater diplomatic crisis. Perhaps the French really had forgiven the murder of Brûlé. But surely, they’d exact a terrible revenge for the death of one of the revered Jesuits.

The goal of the Council may have been to intimidate the Jesuits into leaving of their own accord. That way, perhaps everyone could save face, and there might still be hope of repairing the relationship in the future.

Part of the problem the Wendat faced was that economic growth—in this case, from trade on the St. Lawrence—tends to inevitably produce new forms of economic surplus, which in turn can exacerbate wealth inequalities, even in a relatively egalitarian society. And so there were concerns that certain Wendat elites were not only benefiting disproportionately from the fur trade, but even prioritising their own economic fortunes over the safety of the community. Why else were these outsiders tolerated, even as they seemed to be spreading death across the Confederacy?

For their part, Brébeuf and the other Jesuits refused to be intimidated, and continued their work in Ihonatiria. In fact, the missionaries may have taken the danger as a positive sign—the first indication that the glories of true martyrdom may actually be possible in Canada.

As we’ve discussed previously, the education received by young Jesuits during this period often focused on dramatic tales concerning the deadly perils of missionary work in Asia. And once they’d arrived in Canada, the Jesuits were disappointed by the (initially) casual attitude that local Indigenous communities evinced toward matters of faith.

As we shall see, however, those deadly perils would soon come.

In Spring 1637, the danger to the Jesuits temporarily subsided as the second epidemic ran its course. But the reprieve proved brief. In the summer, yet another epidemic spread through the region (this one originating from the English at Virginia, then brought northwest by the Susquehannock). During the previous epidemics, the French had gotten sick, too, a fact that somewhat insulated them from suspicion. But this time, the Jesuits and their support staff were fully immune—which proved more a curse than a blessing.

Suddenly, village leaders weren’t simply issuing warnings to the Jesuits about rogue elements, but actively amplifying the accusations. Brébeuf and his colleagues now avoided certain villages altogether, and abandoned their territory in the north, moving their base of operations to Ossossone.

In August, the village hosted a meeting of the Confederacy Council. Normally, such a meeting was attended by the civil chiefs of the Confederacy. But with so many of them dead, many war chiefs took their place. This was bad news for the Jesuits, as the duties of war chiefs included protecting their communities from witchcraft.

The Council presented the Jesuits with a compromise. If they admitted responsibility for the epidemics, and explained how they engineered them (thus breaking the spell), they would be forgiven.

Brébeuf, not surprisingly, flatly denied the charge, and started another sermon on the need to convert to Christianity. But the spirit of civility had been exhausted. Brébeuf was interrupted several times, and some chiefs simply walked out. One ominously warned that if a Jesuit were murdered, the Council would take no action to punish the killers. These were shocking violations of Council decorum. The entire political and social structure of the Wendat world seemed to be disintegrating.

The Council concluded without reaching a decision on the Jesuit problem. The Wendat leaders agreed that it would not be prudent to take action while the season’s trade convoy was still on the St. Lawrence. Until they returned, the Wendat traders were potential hostages.

This inaction emboldened the anti-Jesuit faction within Wendat society. In October, the Jesuit cabin outside Ossossone caught on fire. Brébeuf and his colleagues survived, but suspected arson. And once the traders returned a few days later, rumours spread of a plot to kill the Jesuits while their supporters within the Wendat community were off fishing.

But the Jesuits couldn’t be scared off. That’s because the Wendat were absolutely correct that men such as Brébeuf were obsessed with death—specifically, their own. Martyrdom was their fondest ambition, even if the reality of how it might occur likely frightened them. Their rigorous training had prepared them to master such fear and embrace a glorious death at the hands of unbelievers.

At this fraught juncture, however, the Wendat political order just managed to hold. There is evidence that the beleaguered Wendat elites, being committed to the maintenance of the French alliance, protected the Jesuits from the Wendat equivalent of lynch mobs. Plots against them were uncovered and discouraged, sometimes through bribes. By November, the epidemic petered out, and tensions gradually eased.

The waves of disease that hit Huronia from 1634 to 1637 represented the first great test of the Franco-Wendat Alliance. In effect, the partnership survived because the Wendat leaders blinked first. They were willing to use every instrument of persuasion and influence at their disposal to protect the Jesuits (and, by extension, the alliance). This came at a tremendous cost in terms of social cohesion, but that was a cost they felt they had to pay.

As it happened, the French at Quebec were equally dependent on the alliance. Without it, the settlement on the St. Lawrence would not be viable; as there would be little fur to be had. Unbeknownst to the Wendat, it’s likely that even if one of the Jesuits had been killed, the French would have been willing to accept a diplomatic compromise—such as blaming an individual rather than holding the Wendat as a whole accountable. The French simply lacked the ability—and motivation—to exact the kind of vicious retribution the Wendat feared.

The epidemics had wide-ranging economic consequences. Invaluable experience and knowledge was lost with the deaths of so many prominent men and women—whether in the realm of warfare, diplomacy, engineering, or agriculture. Many villages relocated ahead of schedule in the coming years, as they downsized to accommodate smaller populations. Some, especially in the north, may have lost as many as half their inhabitants.

The volume of the fur trade—which involved Wendat middlemen using corn to procure Algonquin-procured animal skins—also declined. The fact that harvest levels recovered in the 1640s much faster than population levels suggests tremendous upward pressures on production and efficiency.

And then there was the military threat from the Haudenosaunee, which lay in the background of every Wendat decision made vis-à-vis the French. As we’ll see in the next instalment, these southern neighbours would not remain idle while Wendat society was riven by disease and political dissent.