Politics

Getting China Wrong

American conservatives show no interest in understanding their country’s greatest geopolitical foe. The consequences of this incuriosity could be disastrous.

During the 5th century BC, cold-blooded Chinese general, military strategist, and theorist Sun Tzu wrote The Art of War, in which he offers this advice to leaders hoping to prevail on the battlefield:

Know your opponent and your own strength, and win 100 percent of your battles. Know yourself but not your enemy, and win half. Know neither yourself nor your enemy, and lose every engagement.

This wise advice might now usefully be applied to US relations with China. As a lifelong student of China and committed critic of communism, who has just returned home from teaching at Peking University, I wish my fellow conservatives would listen.

Unfortunately, the administration is not listening. In early April, America’s vice president J.D. Vance displayed how little he understands China when he complained, “We borrow money from Chinese peasants to buy the things those Chinese peasants manufacture.” That oddly incoherent comment (is someone who works in a factory or engages in international finance still a “peasant”?) typified the reflexive contempt and hostility many American conservatives express towards our superpower rival. This kind of rhetoric is entirely counterproductive, but it is spilling into public policy.

Ignorance of Ourselves

The United States is not calculating its own position in the world carefully enough, or noticing how that position has changed since the end of what some are now calling the “first Cold War.” So yes, we should begin by assessing our own strength—counting tonnage and launch capacity of aircraft carriers, surface ships, and subs. And we might follow that inventory with questions like these: Are our flattops vulnerable to Chinese hypersonic missiles? Might the shallow Taiwan Straits be laid with smart mines that target our vessels? How many missiles have we sent to Ukraine, and how many do we have left? Can we build expensive, top-of-the-line drones fast enough to confront China’s vast drone industry and new flying carriers, even if China cuts off access to rare earth minerals?

We should also check our bank balance. On the debit side, Americans now owe more than US$110,000 per person to creditors. Given how much trouble we have had with Iran, a country that would rank twentieth among China’s provinces by GDP, it is worth asking if we can we afford a new superpower conflict. On the credit side, we should take stock of our allies (or at least, those who remain after months of mercurial tariff policy and “51st state” trash talk). Distant, declining Europe will not be of much help in a confrontation with China, especially after we’ve insulted them, abandoned Ukraine, and adopted a predatory position on Greenland. Canada is feeling even less congenial.

We must ask some sober and critical questions about Taiwan, too, if that is to be the flashpoint. Are the people of that island ready to defend it from an attack by a vastly more powerful enemy? That they wish to remain free, I do not doubt. Having lived in Taiwan for five formative years, I would hate to see that beautiful land conquered by the CCP and turned into another gaudy “native cultures” trap for China’s vast Wooden Indian touring-industrial complex. (This has already been the fate of so many exotic and beautiful parts of China.)

But after circling the island by train recently and chatting to its inhabitants, I wonder if they are willing to pay such a high price for independence. Why did Taiwan’s defence spending drop to a mere two percent of GDP early this century? (And why is it still only about 2.5 percent?) At the beginning of 2024, Taiwan increased compulsory military service from four months to a year. However, Defense News reports that:

One year after the conscription reform implementation, Taiwan’s military faced several setbacks in the enactment of its plan. According to a 2024 report by the Washington Post, Defense Minister Wellington Koo acknowledged that equipment and instructor shortages have delayed plans to improve training for reserves. In 2024, only 6% of conscripts eligible for the one-year military service chose to enlist, with most choosing to defer service to attend university. Due to the small intake of one-year conscripts, drones, surface-to-air Stinger missiles and antitank rocket training was postponed for the cohort.

These disappointing results demonstrate that without properly addressing systemic flaws within the military and the conscription system at large, reform efforts could fail. The conscription reform has demonstrated that systemic issues have had a negative effect on the military conscription system. Taiwan’s military personnel fell from 165,000 in 2022 to 153,000 in 2024.

And what’s with this poll, that puts Taiwan at the very bottom of an international survey of patriotism? When I asked Taiwanese about China, a number of them simply replied, “I ignore politics.” Before we go to war over Taiwan, Americans need to determine how serious the island’s inhabitants are about taking point, with their own cities as battlegrounds. It would be absurd to engage a well-armed foe for the freedom of a country too full of bubble tea to take on a neighbouring superpower.

And we need to calibrate relations with Japan, South Korea, the Philippines, Vietnam, Australia, and most of all, India, which is now the most populous country in the world. Under what circumstances would these countries help us to help Taiwan? Does India only want support to deter or threaten Pakistan during their periodic dustups and to keep China from seizing land in the Himalayas (where mobs of troops periodically brawl)? Or, as Indian GDP rises, will it help to deter the dragon elsewhere in Asia as well? And if China blockades Taiwan, what will Japan be willing and able to do, since its own cities lie within range of Chinese and North Korean missiles (especially now that we are threatening to impoverish our best Asian friend with tariffs)?

I am not even arguing that we shouldn’t help Taiwan. But we need to formulate achievable goals, shore up alliances, count the cost, and make the necessary resources available. None of this is being done at present. This is a conversation Americans need to have before we blunder into what might quickly turn into our worst war. Politicians have a tendency to rush in where Blue Angels fear to tread.

Ignorance of China

Having studied China for more than four decades, I believe that America is badly misreading its strength. Many China hawks have a relentless drive to disparage and underestimate the civilisation across the Pacific, often with outdated stereotypes and ignorance of actual conditions. Conservatives only welcome bad news from China. The country is weak, full of poverty-stricken “peasants,” and possibly about to collapse altogether (as Gordon Chang forecast decades ago). Alternatively, it is a ruthless, bloodthirsty, miserable, Orwellian surveillance state which would just as soon nuke you as look at you. Or it is both? A country at once fragile and cruel—a “Potemkin village” of gaudy skyscrapers and wide boulevards in major cities hiding great expanses of grinding poverty.

I hear such fantasies in countless permutations, but reality remains stubbornly uncooperative. Instead of collapsing, Chinese GDP per capita has grown six times since Chang predicted the present regime’s imminent demise. But America’s conservative press routinely downplays the vast growth in prosperity, productivity, and even some aspects of individual liberty that I have witnessed since I cautiously crossed the border from Hong Kong to Shenzhen in 1984. (Although Xi Jinping is reverting to repression in many respects, the average Chinese has gained undreamed of freedoms since the Deng Xiaoping era: freedom to travel domestically and internationally, to have more children, to buy and sell, to access information, including—for hundreds of millions—by means of VPNs.) And my experience teaching at Peking University and travelling around the country mocked the one-sided pessimism I encounter almost everywhere in America’s conservative media.

Dutch sinologist Frank Dikotter assures us that the grand highways leading out of China’s cities quickly peter into dust. Returning to Beijing after smoothly travelling the countryside of southern China by bus, I found that National Review had linked to a conversation between Dikotter and Hoover Institution scholar Peter Robinson titled “Empire of Illusion: Why China Isn’t a Superpower,” which included this exchange:

Robinson: So a transformation has taken place.

Dikotter: Absolutely. The question is what kind of transformation? ... You will find out that those beautiful manicured highways with roses all along from Tianjin or from Nanjing or from Shanghai, out of the city at some point become sort of dusty roads and then disappear altogether in the countryside.

I have found no such thing. The discs in my back ruthlessly gauge any change from pavement to potholed dirt track, and I find roads to towns that most Chinese have never heard of are paved and in good shape. If you think I may have fantasised those rural highways (or the glistening new airports and the world’s vastest web of high-speed rail), just open Google Earth. Pick a backwater city—say Wenshan in Yunnan, or Linfen in Shanxi, both of which are well off the tourist track—and follow the pavement north or west.

I’m guessing Dikotter hasn’t travelled in rural China for a while. Nevertheless, his voice of “expertise” is typical of what is presented to a conservative readership eager to believe in Potemkin villages. He went on to tell Robinson that “the state is rich and the people are poor,” and that most Chinese are still “rural,” if you include (as he bizarrely insisted we should) tens of millions of former peasants who now live and work in the city. (While he didn’t speak of “peasants” working in manufacturing and international banking, he seems to share Vance’s expansive notion of “agricultural worker.”)

In fact, China is now a middle-income country, above Mexico but slightly behind Malaysia in per capita income. Most Chinese live in towns, where even many rural immigrants do fairly well. How do I know? I ask them! On one journey, I shared a minibus with a young woman who had just earned her MA from a good but not top university. She was hesitating between an offer from a bank in the city of Chongqing (Chungking) and a position with a rural government. Both positions paid about 9,000 yuan (US$1,400) a month, plus benefits. That’s normal in modern China, not the “dollar an hour” or “pennies an hour” so often assumed and claimed. Poor? Maybe by Manhattan standards. But her parents (one was a worker) likely made a hundred yuan a month or so at her age. She later messaged me after a brief trip to Japan: “The shopping is great!”

But conservative journalists seize upon expert opinion that supports the “Potemkin Village” narrative anyway. For instance, in December 2022, Jim Geraghty at National Review cited an analysis of light emitted by countries allegedly showing that autocracies overstate their growth rates by 35 percent. “More economic growth,” we are told, “means more buildings, and more buildings means more light at night.” From this alleged dearth of illumination (I often used to wish they’d turn the lights off at night), Geraghty deduced: “Maybe China isn’t the rising superpower—about to overtake the U.S.—that so many inside and outside of China have claimed for years. Maybe it’s a lot of smoke and mirrors...”

This kind of misplaced scorn soon filters down into popular dialogue. Vance is not the only person to resurrect the term “peasant” to describe the “masses” of modern China, as if the country were still trapped within Pearl Buck’s 1931 novel The Good Earth. A decade ago, I was teaching on the rural fringe of Changsha, a city that defines “inland.” (Hudson Taylor, founder of the influential China Inland Mission, died there.) One day, a friend in America informed me that, while China’s coast may have developed, the country also included a vast hinterland of hundreds of millions of “half-starved peasants.” I told him that I had just strolled past some of those “peasants” above the lotus fields over the hill, and they were washing their car and having a water fight.

Others tell me that foreigners are followed everywhere they go in China (I have travelled tens of thousands of miles around the country with no such accompaniment), women must cut their hair short (I bump into poles for all the long-haired beauties near campus), or that communism has turned the country into an ethical wasteland: “Even many Chinese will admit that there is no morality in China, it is eat or be eaten, and there is no social cohesion or sense of purpose.”

Stories of Chinese immorality and callousness are not new. In the 19th century, Taylor described how fishermen ignored his entreaties to save a man who had fallen into the sea. In the 1920s, British major Warnie Lewis wrote to his brother (C. S.) from Hong Kong, and told him that Chinese merely laughed when a friend was struck by a car. (For what it’s worth, I trust Taylor’s account, but not Lewis’s, which came to him second-hand from an Indian tailor on Hong Kong’s Golden Mile.) But where would you rather lose your wallet? In modern Brooklyn? Or in Beijing, which has far fewer drug addicts, where strangers on the subway warn you when your backpack is left unzipped, and where young women dance alone by canals in the dark?

In fact, modern China is one of the most moralistic societies on Earth—often obnoxiously so. For those with an interest in painting the worst picture of China possible, the unwelcome truth is that, before COVID-19, China had become a pretty pleasant place to live. Then came the pandemic and the lockdowns. No one could possibly know how many people were really dying in China, Geraghty declared. Lockdowns didn’t work in America, so they could not possibly have worked in China either. The problem, he explained, is that China is “opaque,” which allowed him to scoff at the country’s official COVID figures (which were doubtful, like many figures from those days):

Even if we want to give Chinese policies of city-wide lockdowns and quarantining people by welding apartment doors shut the broadest possible benefit of the doubt, it’s simply not plausible that a virus that has proven wildly contagious in every other country suddenly became shy and socially-awkward once it entered the jurisdiction of the Chinese Communist Party.

A good line, I suppose. But there are only two possibilities. Either the CCP’s polices really did control the spread of COVID-19, at least until the more profligate but less murderous Omicron variant asserted itself. Or those policies failed, the virus ran rampant in 2020, and millions of unaccounted-for Chinese died—probably at least four million, by analogy to the United States, given a younger and less obese population. Hundreds of thousands of foreigners lived in China in 2020, and most of them had networks of friends, some of whom were doctors and officials. Chinese can be chatty in private, including about sensitive topics. So, how is it that sceptical journalists have never found those millions of bodies? (Which by demographic logic, must have included hundreds or thousands of foreigners?)

Then in 2022, Omicron broke out, people in Shanghai began banging pans, and journalists found they could, after all, report detailed and specific facts from China, including deaths more than four orders of magnitude fewer than the posited yet invisible millions. There seems to be an iron rule in America’s conservative press: Deride Chinese statistics, unless they affirm the critical point I wish to make. Then twist the knife by saying, “Even official statistics admit X, so the reality must be five times X at least!”

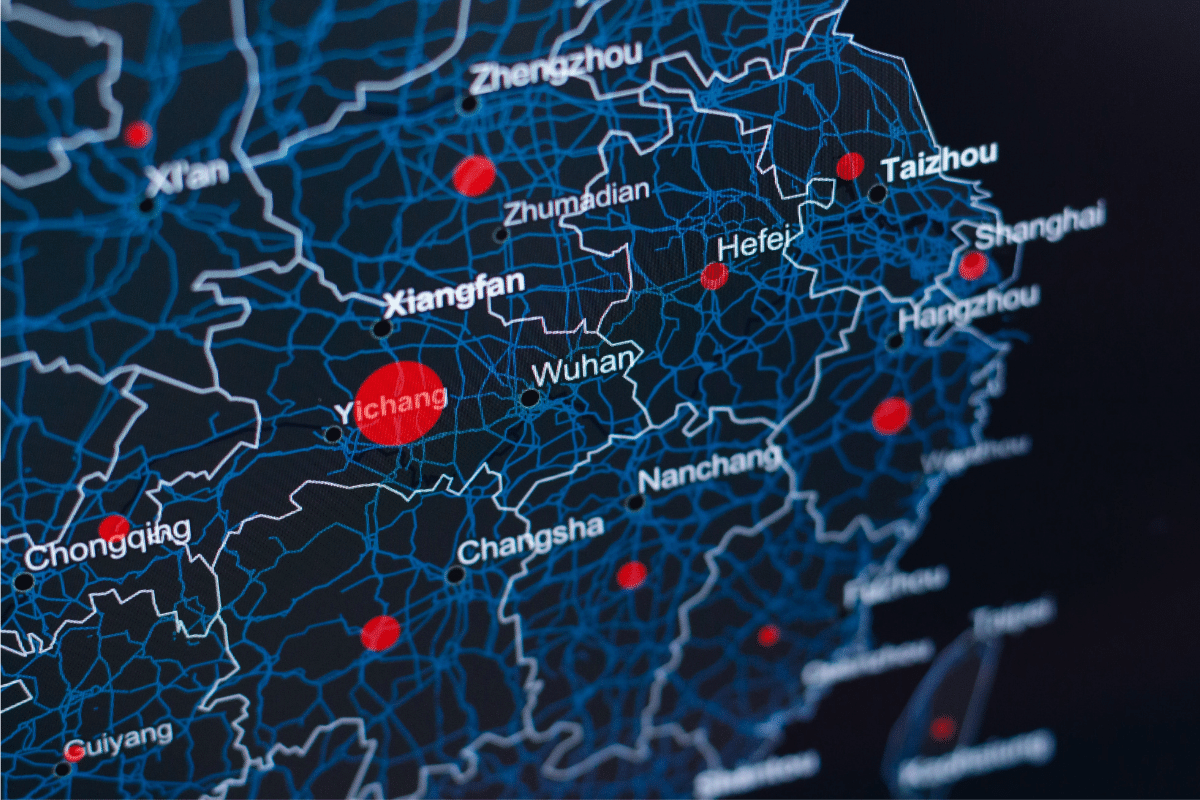

Reporting on COVID-19 took an even more bizarre twist in 2021, when House Republicans released a report on the origins of the pandemic. In that document, they argued that the SARS-Cov-2 virus had been accidentally released from the Wuhan Institute of Virology. But Geraghty noticed an odd detail. Late in the summer of 2019, the Institute had requested bids to repair the building’s air-conditioning at the astounding cost of more than US$600 million. House Republicans reported the billing as follows: “Central Air Conditioning Renovation Project September 16, 2019 … $606,382,986.11.” The Institute’s main building appears to rise some eight floors. At the time, Amazon was building an 850-foot (259-metre) skyscraper in downtown Seattle for about that price. How could fixing the AC in a relatively small office building cost most of a billion bucks?

Geraghty pondered: “The sheer size of the sum of money in that contract raises the question of just what the contractor was really being asked to do.” Geraghty provided a link to the original document in Chinese and invited readers to Google translate it. That evening, Tucker Carlson cited the same mind-boggling figure on his then-popular Fox show. Scanning the document in Chinese, I found two references to the price tag. Both say 3,926,876.94 yuan which is about US$600,000, not US$600 million. So, the House Republicans, National Review, and Tucker Carlson foisted a blunder on millions of Americans that the waiter bringing you Dan Dan noodles at your favourite Sichuan lunch dive could have corrected at a glance.

I could fill a book with examples of how the conservative press is failing in its China reporting. But the main point is that if we are going to see China as our enemy, we had better see it clearly. As Sun Tzu advised, if you don’t know your opponent, you are setting your armies up to get crushed. So, it is important that we evaluate China and its assets objectively—and not just its shiny new hypersonic missiles, robot warriors, smart mines, and lousy (so far) carriers. We also need to count its vast productive capacity, in rare earth minerals, iron, ships, cars, seventy percent of the world’s drones, and now aircraft.

China’s assets also include a high-tech society that runs remarkably smoothly. Planes seldom crash. Trains arrive and depart on time. With a smartphone in hand, you can travel almost anywhere in hours—first, over more than fifty clean and efficient subway networks, then on trains radiating out from vast, crowded stations at 230 miles (370 km) an hour. Since the founder of the Xia Dynasty harnessed manpower to tame the waters of ancient China, top-down control has given China certain advantages, which our own grassroots genius should not tempt us to overlook.

The CCP can also count on a patriotic citizenry that is not generally anti-American, but that reacts with quick anger to perceived national slights or threats. All the boys in the small high-school class I taught in Changsha spontaneously spoke up one day and announced (off topic) that, if China went to war, they would quit school and enlist. They wanted to go overseas to study, probably in America, and we enjoyed a good relationship. But love of country came first. They didn’t even ask if, in that scenario, the national cause were just.

Of course, we should toss China’s problems into the mix. Like a number of other nations, China is due a demographic collapse. Half my students didn’t even want to have children. AI is swiping the jobs of their hypothetical offspring, anyway. Will the peasants revolt, as Joel Kotkin has suggested in an article for Quillette? This has often occurred in China’s past.

But as I argue in my rejoinder to Kotkin, that won’t happen again. An ageing and dispersed remnant remains to farm. (And some of them have other gigs—like my regular taxi driver in Qingdao, who also owned peanut fields, and my landlady, who grew green beans on the hill above our high-rise apartment.) Children and grandchildren of China’s “peasants” are now building trains, delivering goods, and selling coffee in the city. However expensive it becomes to raise and educate children, they are not about to revolt—they lack the means to do so even if they wanted to. Bird guns—used by “peasants” back when the roads they walked looking for feathered prey really were made of dirt—were outlawed years ago.

A realistic appraisal of China must soberly consider the country’s many strengths. China was once a peasant society. Then it developed an export economy, but it now exports a third less as a percentage of GDP than the world average. Only 2.5 percent of Chinese GDP comes from exports to America, so no, the CCP is not going to collapse under the weight of US tariffs, as some have been dreaming it will.

Is a New Cold War Necessary?

In National Review, Tom Cotton has called for a “targeted decoupling” as part of “a new cold war that will determine the future of our nation and of the world.” Other conservatives wish to cut off trade entirely, and speak of a hot war as inevitable, if not desirable. But is conflict really necessary? Are we so sure that Cold War II would bring a repeat of our encounter with a far weaker and smaller Soviet Union? (Which might also have ended very badly, by the way.)

Attempting to avoid unnecessary conflict does not necessarily entail appeasement of Chinese aggression or mean that we shouldn’t pressure China on behalf of the Uyghurs. It doesn’t even mean we shouldn’t help Taiwan if it is serious about self-defence. Xi Jinping’s hometown of Beijing might still be part of imperial Japan today were it not for Admiral Nimitz and the Flying Tigers. If America again helps a weak country against a stronger one, Xi should be remember to be grateful for his own country’s independence. And perhaps he should stop complaining that it has yet to conquer the island that preserved so much of Chinese culture when Mao and his gang were torching that heritage on the Mainland (and abusing Xi’s family).

Americans must look at China with both eyes open, willing and able to acknowledge the good and the bad. If you think there is nothing impressive or praiseworthy about modern China, then you should admit your ignorance, and stay out of the conversation. I used to tell my students of the good America has done their homeland. Then they would travel to America, make friends, and report back absurd stereotypes to my embarrassment and the enjoyment of the rest of the class. Yet the failure of America and China to understand one another is no longer a laughing matter. Sun Tzu tried to warn us about the pitfalls of cocky and ignorant militancy. Our countries should take heed.

Aaron Sarin’s reply to this essay can be read here.