Iran

Atomic Jihad

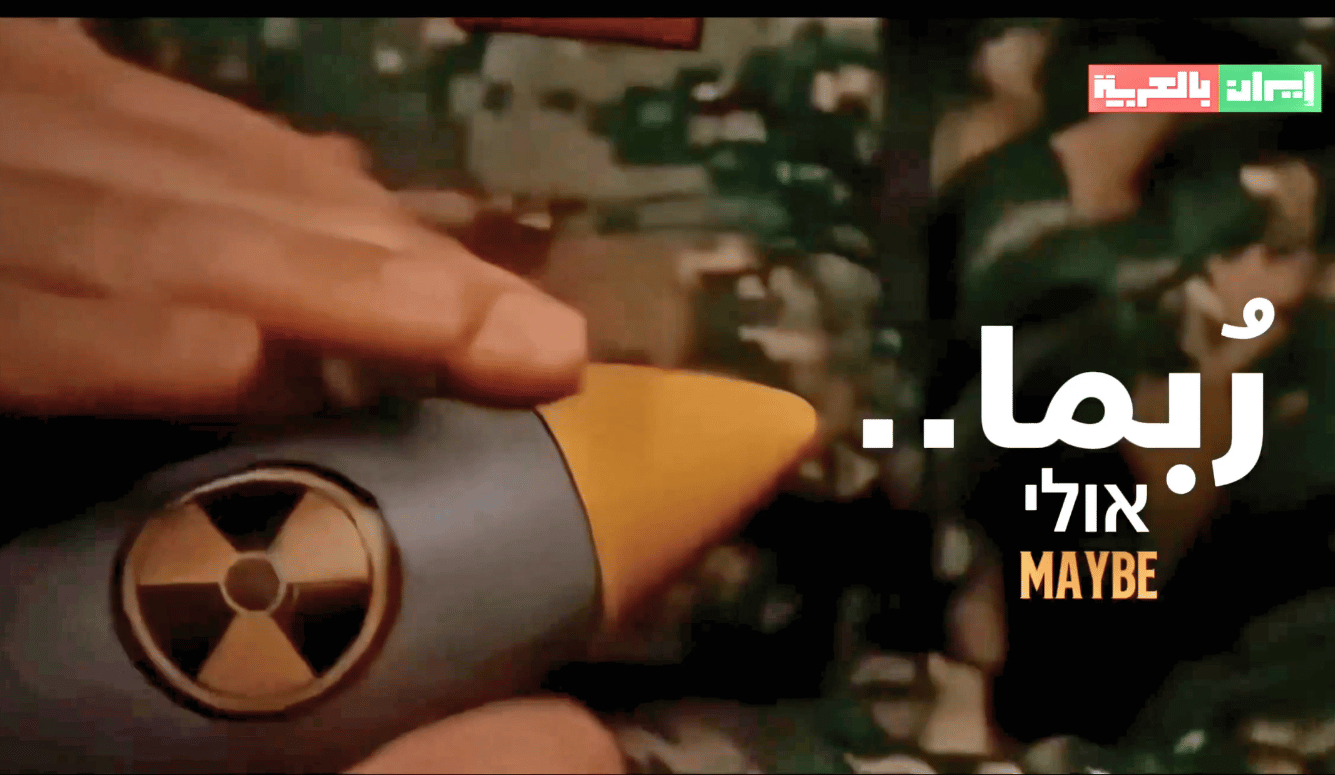

Why we must never allow Iran, an absolutist theocracy whose leaders see martyrdom as a sacred calling, to obtain nuclear weapons.

When India tested its first nuclear device in 1974, the test was codenamed Smiling Buddha and billed as a “peaceful nuclear explosion,” though no one was fooled. Delhi was clearly staking its claim to be a world power. Two decades later, in 1998, Islamabad unleashed its own nuclear weapons project—Chagai-I—with a flurry of underground detonations in the Baluchistan desert. The “Islamic Bomb,” as some Western commentators called it, had arrived. The Clinton administration condemned both sets of tests, levied sanctions under the Glenn Amendment, and warned of an arms race on the subcontinent. The US knew that it could not uninvent the bomb but the logic of mutually assured destruction safeguarded the two countries. India and Pakistan, it turned out, preferred tense coexistence to mutual annihilation. In each case, the world adjusted. India was eventually welcomed into a strategic partnership with the United States. Pakistan, while unstable, is treated as a necessary evil.

Then came North Korea. The collapse of the Soviet Union had left Pyongyang isolated, economically crippled, and geopolitically paranoid. The Clinton administration brokered the 1994 Agreed Framework, offering fuel oil and civilian reactors in exchange for a freeze on North Korea’s plutonium program. But by the early 2003, the deal had unravelled. George W. Bush labelled Kim Jong-Il’s regime part of the “Axis of Evil,” and Pyongyang, feeling encircled, withdrew from the Non-Proliferation Treaty. Three years later, it tested its first nuclear weapon. The global reaction was swift, but mostly symbolic: sanctions and international condemnation. Yet North Korea endured, sustained by Chinese supplies.

These precedents are often invoked to reassure us that if the world survived those nuclear awakenings, surely it can survive a nuclear Iran. But Iran’s case is different.

The reason the free world tolerates North Korea—or, at least, has refrained from a serious campaign to disarm it—is because it understands the regime’s rationale. Pyongyang’s nuclear arsenal is not a tool of conquest but a hedge against collapse. Brutal, tyrannical, and hermetically sealed though the country is, the Kim dynasty’s primary goal is to be left alone to govern without foreign interference. Its arsenal is less a projection of strength than a shield against extinction. The regime remains preoccupied not with expansion but with survival.

Choe Son-hui, longtime director-general of the North American Department at North Korea’s Foreign Ministry, insists that the bomb is the regime’s sole guarantee of sovereignty. “We will not follow the precedents of Iraq and Libya,” she has warned, alluding to regimes that surrendered their nuclear arsenals and were toppled soon after. As another senior official put it to a delegation of American experts: “If you remove those threats, we will feel more secure and in ten or twenty years’ time we may be able to consider denuclearisation.” By “threats,” he means the US–South Korea alliance, the presence of American troops in the peninsula, and the nuclear umbrella that defends both Seoul and Tokyo.

Even North Korea’s most belligerent acts follow this logic. Take the shelling of Yeonpyeong Island on 23 November 2010. That morning, South Korea was conducting live-fire drills near contested maritime borders. Although the artillery was aimed southward away from the North, Pyongyang declared the exercises a provocation and demanded they be halted. When Seoul continued, North Korea launched approximately 170 artillery rounds, over eighty of which landed on the island, damaging military sites and civilian homes in the first direct artillery strike on South Korean territory since the armistice.