Free Speech

Blasphemy, Censorship, and the Future of Free Expression in Britain

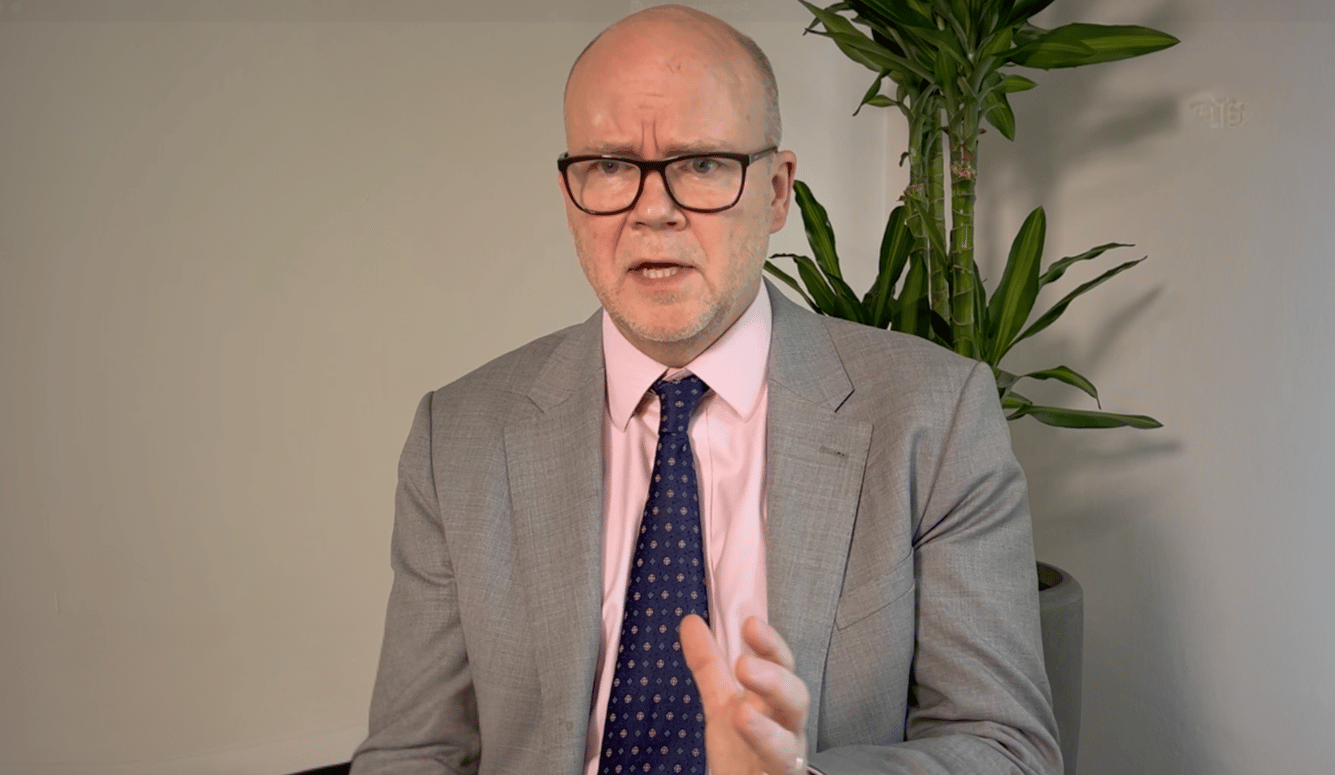

Pamela Paresky speaks with former Quillette editor Toby Young, founder of the Free Speech Union and recently appointed member of the House of Lords, about the current state of free expression in the United Kingdom.

This interview was conducted in London in June 2025 by Pamela Paresky.

Transcript

Toby Young:

We had a verdict in the case of a Turkish political refugee called Hamit Koskun, who was arrested and prosecuted for burning a copy of the Qur’an outside the Turkish consulate in London. The Free Speech Union and the National Secular Society paid for his defence. The judge issued a written verdict, which he has just read out in court—literally minutes ago.

And it wasn’t the verdict we were hoping for. He has been convicted on one count, and the judge has adjourned making a decision about the second count, pending whether or not there’s an appeal. So it’s quite a complicated verdict. I’ve been working with my team to figure out how to respond on our socials, and we need to do so quickly because the story is just breaking.

But it’s obviously disappointing, and we will help Hamit get that judgment overturned. If that means appealing all the way to the European Court of Human Rights, then that’s what we’ll do.

PP: What’s the law under which he could be convicted for that?

TY: Well, he’s been accused of a criminal offence under two different laws. One—I’d literally have to check—but one is Section 5 of the Public Order Act 1986, and the other is under the Crime and Disorder Act 1998. The actual offences are very similar. I’m not sure I fully understand the difference between them.

The gist is that he used disorderly behaviour within the hearing or sight of a person likely to be caused harassment, alarm, or distress—which is a pretty broad standard, and is, in fact, very broad. And his behaviour was deemed to be religiously aggravated—that is, he was motivated in part by a hatred not just of Islam, but of Muslims. So it’s a religiously and racially aggravated offence he’s been found guilty of.

It won’t mean a prison sentence. The judge hasn’t sentenced him yet—that’s happening as we speak—but he’s likely to be given a fine. The National Secular Society and the Free Speech Union will pay that fine.

I attended part of the trial last week. One piece of the prosecution’s evidence that his burning of the Qur’an had caused harassment, alarm, or distress was that two members of the public—both Muslims, one wielding a knife—attacked him.

It’s a truly extraordinary argument: if a devout Muslim violently attacks you because of something you’ve done, then you’re guilty of having caused him harassment, alarm, or distress. It’s not quite a heckler’s veto, but something quite similar.

It effectively means that non-believers must respect Islamic blasphemy codes—or risk causing offence by violating them in public. That feels like a Trojan horse for reintroducing a blasphemy law by the back door—a law that only applies to Muslims, or to other religious groups that respond similarly.

The police have generally given much wider berth, much more latitude, to pro-Palestinian protesters than to anti-Islamic protesters. You’ve likely heard the accusations of two-tier justice and two-tier policing in the UK. Often, what people mean by that is the extraordinary tolerance shown by authorities toward pro-Palestinian protesters, and the intolerance shown toward other, less fashionable causes.

PP: Just one more question about this case. Were the people who attacked the Turkish protester arrested?

TY: He’s been attacked four times now. The Free Speech Union paid for his security when he came to court and will also pay for his transport back to his safe house. Of the four people who attacked him, only one is being prosecuted.