Politics

After Liberal Internationalism

The post-11 September wars set in motion political forces that constrained and undermined American power at the moment it was needed most.

The is the second instalment of a two-part essay. Part One, The Rise and Fall of Liberal Internationalism, can be found here.

I.

On 13 June, the long-simmering confrontation between Israel and Iran finally erupted into open state-to-state warfare when Israel began to hit Iran’s nuclear infrastructure and scientists, military leadership, government buildings, and military assets with relentless waves of airstrikes. Then, on 21 June, US President Donald Trump announced that American warplanes had struck Iranian nuclear facilities at Fordow, Natanz, and Isfahan. Three days later, a fragile ceasefire was announced, which is still holding at the time of writing. For years, American presidents have worried that an Israeli military assault on Iran’s nuclear facilities would destabilise the entire region. But no region has more reliably confounded expert assumptions and predictions, and—for now, at least—those fears appear to have been misplaced. After a desultory response to the US strikes, Iran seems to have acquiesced to Trump’s demands for calm.

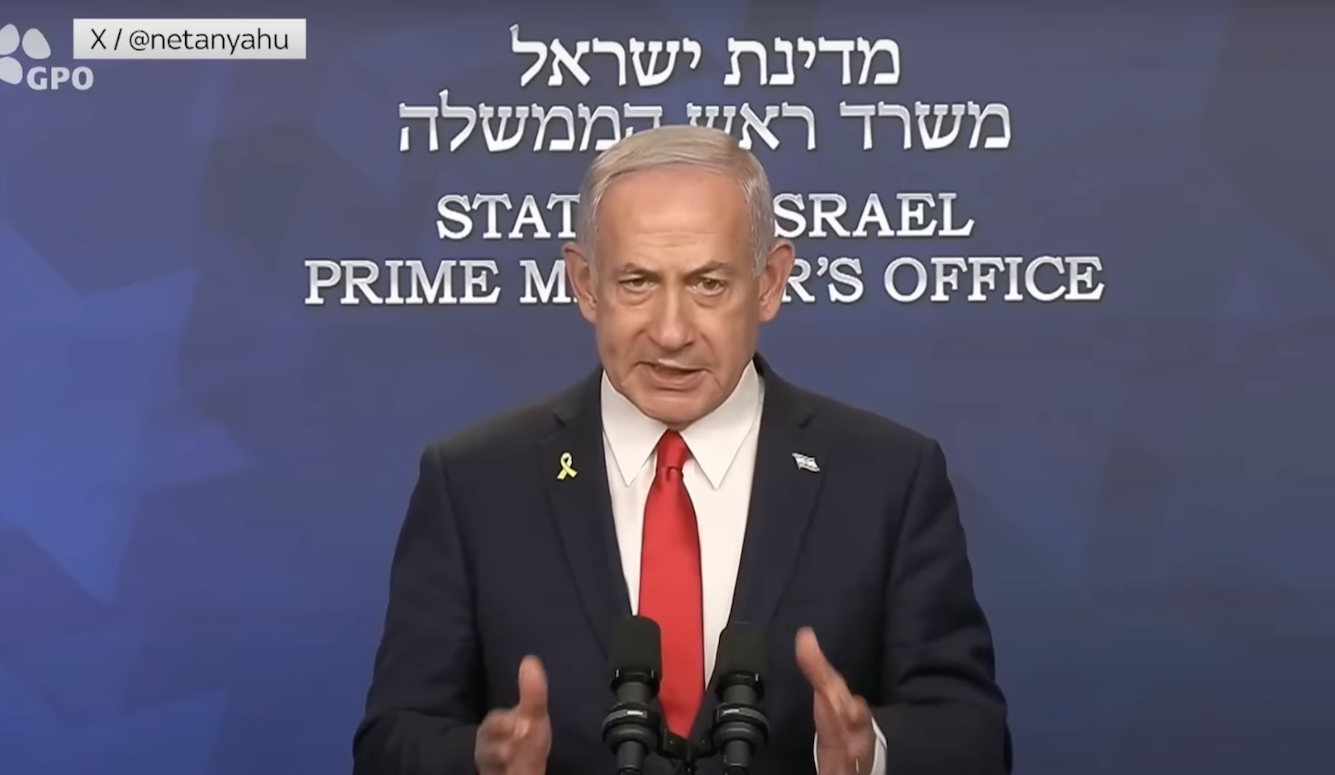

The Israeli and American airstrikes were conducted at a time of acute Iranian vulnerability. Since the Hamas attacks on 7 October 2023, Israel has been systematically extinguishing the Iranian “ring of fire” encircling the Jewish state. Hamas has been destroyed as a military force in Gaza. Much of the senior leadership of Hezbollah—including Hassan Nasrallah—has been assassinated in Lebanon, and the terrorist group now seems to have been deterred from mounting further attacks on Israel’s north. The Assad regime in Syria has fallen, and in October 2024, the Israeli airstrikes destroyed much of Iran’s own defensive capabilities. As a consequence of these developments, Iran’s nuclear program was left exposed—circumstances that finally persuaded Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to attempt its destruction. The fall of Assad was a particularly grave strategic blow to Tehran—not only did it cut off Lebanese Hezbollah’s supply routes, but Israeli aircraft were also able to fly through Syrian airspace on their bombing runs into Iran.

In addition to the collapse of its proxies across the region, the Iranian regime is internally weak and unstable. On 16 September 2022, the death of a young Kurdish woman named Mahsa Amini at the hands of the morality police sparked a two-year protest—the largest popular uprising in the country since the Green Movement in 2009–10. The Israeli and American attacks may galvanise some patriotic sentiment among Iranians, but Israel’s penetration of the Iranian command structure suggests that the regime is infested with spies, a discovery that is bound to produce internal paranoia and erratic purges.

Nevertheless, Trump has taken a significant political risk by striking Iran. As I discussed in the first instalment of this essay, the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq made much of America’s public and political class reflexively hostile to the whole idea of military intervention abroad, particularly in the Middle East. Despite the weakness of the Iranian regime—as well as its open hatred of America and sponsorship of terrorist attacks and direct attacks on Americans—a recent YouGov survey found that just sixteen percent of Americans thought the US military should get involved in the Israel-Iran conflict, while sixty percent were opposed. Trump himself was one of the politicians most responsible for mainstreaming antiwar sentiment on the American Right, repeatedly inveighing against the invasion of Iraq during his 2016 run for the presidency. Liberal internationalism has become a political cudgel for populist authoritarians around the world, who present it as a paradigmatic example of elite arrogance, ineptitude, and failure. Never again, they vow, should the political class be allowed to drag Western nations into forever wars with fantasies of regime change, democracy promotion, and nation-building.

However, opponents of the US/Israeli action against Iran are given to overstating the similarities between Iran and Iraq. While Netanyahu has made it clear that he would welcome the collapse of Iran’s revolutionary theocracy, regime change was not one of his administration’s official war aims, and the IDF has neither the desire nor the capacity to occupy Iran—a vast country with a population nine times the size of Israel’s. Notwithstanding the regime’s many and various vulnerabilities, there is no clear path to its overthrow at present. Iranian authorities have already restricted access to social media in anticipation of street protests, and their security services will no doubt crack down heavily should popular unrest erupt.

Still, the situation remains combustible. While Trump confidently reported that Iran’s nuclear program had been “completely and totally obliterated” by the US airstrikes, precise damage assessments have not been made available. The New York Times has reported that:

Satellite photographs of the primary target, the Fordo uranium enrichment plant that Iran built under a mountain, showed several holes where a dozen 30,000-pound Massive Ordnance Penetrators—one of the largest conventional bombs in the U.S. arsenal—punched deep holes in the rock. The Israeli military’s initial analysis concluded that the site, the target of American and Israeli military planners for more than 26 years, sustained serious damage from the strike but had not been completely destroyed.

Doubts also remain about the status of some 880 pounds (399 kg) of uranium enriched to sixty percent—enough to make ten nuclear bombs. A number of analysts are worried that stockpiles and other equipment were moved out of Fordow and other sites in advance of the American attack. It is therefore still possible that Israel’s immediate victory could become a strategic defeat if the regime manages to produce a bomb or if the Iranian state collapses entirely.

Israel will maintain that it had no choice but to execute a preemptive defensive strike on Iran’s nuclear program given the unique combination of opportunity and threat. But its unilateral decision to launch those strikes, and Trump’s decision to join the campaign, have done little to strengthen the idea of a rules-based liberal international order. Supporters of Israel who despise the Iranian regime may be heartened by the apparent success of the operation so far, but it may turn out to be one more step towards an anarchic and lawless international system.

II.

In their 1998 book A World Transformed, former US President George H.W. Bush and his national security advisor Brent Scowcroft explain why they decided not to topple the Iraqi regime of Saddam Hussein after the 1991 Gulf War. They believed that objective would incur “incalculable human and political costs” and force the US “to occupy Baghdad and, in effect, rule Iraq.” They worried that the coalition built to expel the Iraqi army from Kuwait would have collapsed and that there was “no viable ‘exit strategy’ we could see.” Beyond these prescient observations, Bush and Scowcroft summarise the broader geopolitical implications of regime change in Iraq: