Politics

Natalism and the Welfare Mother

In the United States, demographic decline will test conservative support for welfare reform.

The first major legislative effort under the new Trump administration, known as the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act,” is now working its way through Congress. In its House of Representatives version, it expands family benefits and places work requirements on Medicaid (subsidised health insurance for the poor). It thereby seeks to address the priorities of America’s new and old Right. Welfare reformers—an old Republican faction committed to shrinking the state—have long promoted a “workfare” approach to the safety net. Natalists—a rising Republican faction worried by America’s declining birthrates—want government to reverse this trend by giving more aid to families. This coalition is unstable.

Should natalists continue to gain influence, they’ll be on a collision course with welfare reformers over the conditionality of government benefits. Welfare reformers prefer benefit programs to be time-limited, serving only those who are deeply needy and—in the case of the able-bodied—pursuing work. Natalists worry less about conditions. In his 2024 book Family Unfriendly, Tim Carney writes: “Conservatives have a bad habit of worrying too much about the undeserving poor spending money on the wrong things. This is excessively paternalistic and insufficiently merciful.”

Thirty years ago, when America’s welfare debate was truly raging, some conservatives and centrists would have opposed generous cash benefits that increase family size among the low income bracket. But many of these same people now see such benefits as a good thing, precisely because they’ll help increase family size. Whenever societies debate natalism, “cash for kids” proposals are inevitably part of the discussion. In his 2005 book Postwar, historian and social democrat Tony Judt noted that a number of European countries first introduced family allowances after World War I to restore population levels. Ardent natalists perceive demographic decline to be a war-like threat to America and other 21st-century nation states, and a future with fewer people does look austere in many ways. But in America, it may lead to a more expansive attitude toward benefit programs, and convergence with European-style social democracy.

The American welfare-reform movement developed in response to President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society (1964–68). That initiative’s array of expanded social programs left a legacy of soaring crime and family breakdown, and the decline of places like Harlem gave strong support to proponents of American exceptionalism when it came to the welfare state. Whatever the experience may have been in Europe’s social democracies, increased social outlays did not increase social health in America. Welfare reformers’ crowning achievement was the design and passage of the “Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act,” signed into law by Bill Clinton in 1996. That legislation made cash assistance time-limited and contingent on work.

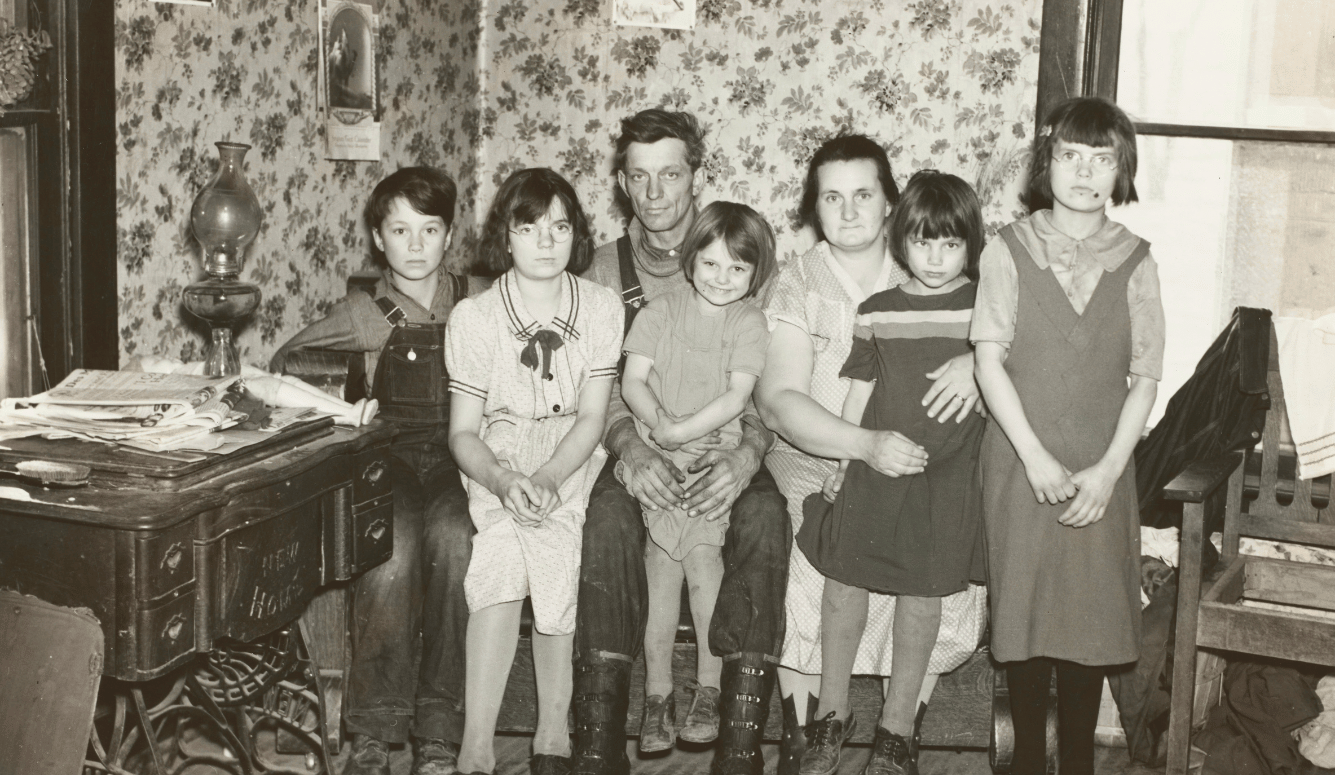

Standard leftwing histories describe welfare reform as rooted in racist obsessions about “welfare queens.” In fact, the real issue was a crisis of supervision. Journalist accounts of urban culture from the pre-welfare-reform era regularly featured single mothers on welfare overwhelmed by their unwieldy broods. Examples include Susan Sheehan’s A Welfare Mother (1976; nine kids), Nicholas Lemann’s The Promised Land (1991; eight kids), and Leon Dash’s Rosa Lee (1996; eight kids). In his 2018 book High-Risers, historian Ben Austen describes Chicago’s notorious Cabrini-Green housing project as an “overpopulated children’s city.” Around 1970, two-thirds of its population was under the age of eighteen. In Savage Inequalities (1991), the education advocate Jonathan Kozol excoriated the massive class sizes inner-city teachers used to have to deal with.