Science / Tech

Ancient DNA and the Return of a Disgraced Theory

This is a story of some of the greatest findings in modern research, and of the dismal narrow-mindedness and motivated reasoning displayed by scholars who ought to know better.

I tell you naught for your comfort,

Yea, naught for your desire,

Save that the sky grows darker yet

And the sea rises higher.

~G.K. Chesterton, “The Ballad of the White Horse,” 1911

For a discipline dedicated to the study of the immutable, history is nonetheless ever-changing. Just as there were revolutions in the past, there have been revolutions in our understanding of it, and few have been as dramatic as the one currently engulfing the fields of prehistory and archaeology. The rediscovery of the Indo-Europeans—dubbed by an article in the New Scientist the “most murderous people of all time”—is the story of our ancestors, of technological progress, and of an ongoing academic upheaval. It is a story of some of the greatest findings in modern research, and of the dismal narrow-mindedness and motivated reasoning displayed by scholars who really ought to know better.

The Rise and Fall of Culture-History

European archaeology has its roots in the antiquarianism and treasure collecting that arose during the Early Modern period. By the 19th century, scientific archaeology in its recognisably modern form was consolidating, though divided into two main branches—the classical archaeologists, concerned with Greece, Rome, and the early documented periods of European societies, and the prehistoric archaeologists (or “prehistorians”), whose work was characterised by the ideas of the Enlightenment.

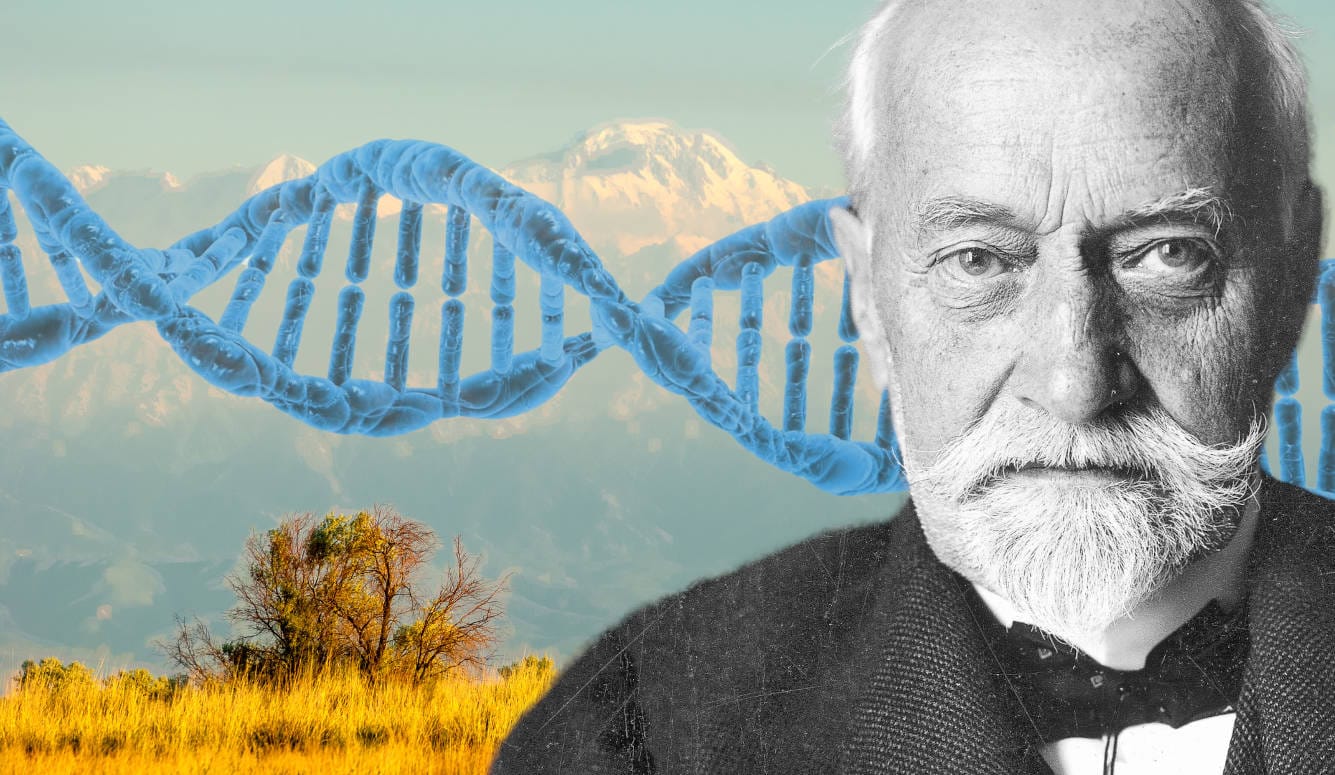

Throughout the 1800s, these two branches began to merge, and there was a growing desire to delineate the roots and traits particular to modern nations. One personage looms large in this story. His name was Gustaf Kossinna (1858–1931). Synthesising prior authors, Kossinna proposed a new historical framework that became known as the “culture-historical model,” which hypothesised the movement of culturally—and biologically—distinct peoples as the dominant driver of historic and prehistoric cultural change.

For the purposes of what is to follow, it is essential that we distinguish the fundamentals of the culture-historical model from those associated ideas which were not central to the model itself. Kossinna’s thesis was that prehistoric Europe can be divided into Kultur-Gruppen—cultural units that correlate directly with specific ethnic groups—and that the movement of a Kultur-Gruppe entails the movement of a physical group of people, and not merely a bundle of cultural artefacts. Kossinna’s model allowed him to pinpoint the history of ancient kinship groups as they migrated, conquered, and settled. This was the crux of his model, and he termed it Siedlungsarchäologie—“settlement archaeology.”

However, the rise of the culture-historical model, regarded as a subject in the history of ideas, cannot be divorced from the racialist, nationalist, and colonialist ideas that characterised late 19th-century and early 20th-century Western thought. All ideas are developed and applied in a particular milieu, and the culture-historical model arose during the high age of European imperialism and race science. Kossinna’s research was as much an exercise in the valorisation and glorification of the German volk as it was investigative science for science’s sake. He described the superiority of the Germanic peoples over the Slavs and other neighbours and derived the origin of the Indo-European languages from a fair-haired, blue-eyed “Aryan” people he traced back to the Maglemosian culture in Northern Germany and Denmark. Like other academics at the time, he divided all ethnicities into Kulturvölker, culturally creative peoples, and Naturvölker, culturally passive, “natural” peoples. It is therefore not hard to see why later archaeologists treated his work with great caution.

The influence of the culture-historical model grew throughout the early 20th century, and for a while, it became the dominant archaeological model in the West and beyond. It remains the predominant interpretive frame in many parts of the world today, including in much of Asia and Africa. In the West, however, Kossinna’s very influence would also be his undoing. Kossinna died in 1931, shortly before the Nazis seized control of his country, but the applicability of his ideas to their aims ensured their enshrinement in the educational curricula of the Third Reich. When the Nazis fell, Kossinna’s ideas were discredited by association, along with the intellectual old guard that had adopted them. Ideas that elevated cultures and ethnicities as distinct and important units, that stressed conflict and conquest as core factors in human history, and which bore in any way the whiff of nationalism and racialism were banished from the intellectual mainstream.

In their place, the postwar era saw the emergence of “processual archaeology,” which held that human behaviour and environmental constraints, not migrating tribal groups, were central to cultural development. This model would, in turn, give way to “postprocessualism,” which rejected processualism as overly deterministic. Postprocessualism favoured a postmodern approach that emphasised human consciousness, social conflicts, gender dynamics, and a pronounced subjectivism. These movements changed the focus of archaeology from groups to individuals and artefacts, rejected the correlation of material cultures with biologically related kinship groups, and downplayed the importance of violence and tribal identity in shaping prehistory.

In the place of conquest and large-scale migration, postwar scholars elevated trade, intermarriage, and the peaceful mingling of peoples and ideas as the dominant culture-shaping processes. Such postmodern and critical approaches still strongly characterise archaeology today, with a marked scepticism towards any sort of grand narratives or clear delineations of ancient people. This scepticism has gradually expanded, increasingly encompassing not merely the centrality of tribal units as explanatory factors in human history, but even their basic existence. Ethnic identity came to be understood as something constructed rather than grown and conserved—social fables that communities tell about themselves. Archaeological cultures were now said to have only the loosest relationship to biological realities. “Pots are pots, not people,” became a mantra in the discipline.

Over the last few decades, a deconstructive approach to ethnic groups has even extended to historically documented migrations and conquests, from the Anglo-Saxon invasions of England to the Dorian invasion of Greece and the Indo-Aryan invasion of India. A sort of diffusionism coalesced that regarded the spread and dissemination of technologies, languages, and ideas as essentially osmotic, organic, but distinctly non-biological processes. A heuristic of nigh-universal doubt regarding the stability and integrity—even the basic definability—of past cultures was rising swiftly to academic hegemony. Then the geneticists arrived.

The aDNA Revolution

In his 2018 book Who We Are and How We Got Here, geneticist David Reich describes the scope and rapidity of a scientific upheaval that is still underway. For the last few years, the field of ancient DNA (“aDNA”) had been experiencing massive growth and rapid advancement. In his book, Reich notes that a New York Times journalist assigned to cover this field expected he would be writing an article on new findings every six months or so. Instead, he found himself struggling to keep up with a new scientific paper every few weeks, and fresh developments were only accelerating.

What is aDNA? In brief, it is the study of ancient genetic material, principally from human ancestors but also from other species. The first major work attempting to apply this science to the study of human history was The History and Geography of Human Genes, published by Italian geneticist Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza in 1994. Beyond the material from his own field, Cavalli-Sforza also drew on archaeology, linguistics, and geography, heralding a synthesis of disciplines that would gain tremendous significance in time. His results, however, were limited, and (as it would turn out) largely inaccurate: in 1994, the technology was simply not up to the task yet.

The big breakthrough would have to wait until the late 2000s, when Swedish geneticist Svante Pääbo and colleagues in Leipzig, Germany began developing novel techniques for the extraction and analysis of very ancient DNA. This work was originally undertaken to study, not the contours of human history, but the genetics of Neanderthals and their Denisovan cousins. Two of the researchers working under Pääbo, Matthias Meyer and Qiaomei Fu, invented a means of isolating and extracting minute quantities of preserved human DNA from bones tens of thousands of years old, drastically reducing the cost and time needed to study archaic genomes.

Two of Pääbo’s other apprentices, Nadin Rohland and David Reich, identified a potential application. Adopting the technique for the sequencing of whole genomes, their work opened up the genetic screening of hundreds of ancient skeletons, enabling cheap, quick, and comprehensive analyses of prehistoric remains in a way that had never been possible before. Indeed, the scope of aDNA research expanded so rapidly after 2009 that all the combined work prior to this time was essentially reduced to little more than groundwork.

What, then, was the main consequence of this great technical leap? In short, the complete collapse of one historical paradigm, and the rise—or return—of another. The first bombshells dropped in 2015 with the publication of a paper, the mere title of which sent shockwaves through the fields of archaeology and linguistics: “Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe.” For decades, the dominant understanding had been that the modern population of Europe was a mixture of aboriginal Ice Age hunter-gatherers and farmers who began arriving about 6,000 years ago.

Cavalli-Sforza’s work, using rudimentary genetic technology, seemed to support this narrative and show that the formation of modern European populations had been a relatively gradual, osmotic process. His results seemed to indicate a pattern of diffusion, with farmer ancestry mixing more and more with the aboriginal hunter-gatherer population as agriculture spread north. These findings fit comfortably with the existing archaeological paradigm, which could accommodate a gradualistic introduction of Near Eastern ancestry: neighbour mixed with neighbour, ideas and spouses were exchanged, and ancestry and technology alike permeated Europe like a drop of paint in the water, thinning as it spread.

Yet this was not the full story. The 2015 paper revealed that a crucial element had been missing. While the mixing of these two groups was indeed the origin of the great majority of ancestry in southern Europe, this was not the case in the north. The people there derived the majority of their ancestry from a third group not anticipated by contemporary researchers, but foreshadowed by the archaeologists of an earlier age. As Reich puts it in his book, “The extraordinary fact that emerges from ancient DNA is that just five thousand years ago, the people who are now the primary ancestors of all extant northern Europeans had not yet arrived.”

Around the end of the Neolithic era, just under 5,000 years ago, and on the cusp of the Bronze Age, a new people had burst into Europe from the steppes above the Black Sea. Bearing a martial culture, an affinity for horses, and a predatory social structure, they swept away the old world they found and inaugurated a new one in its place. They were almost certainly the carriers of the Indo-European languages now spoken throughout nearly all of Europe and beyond. The “beyond” here is significant, for further papers followed, and their findings about India were almost as controversial as those about Europe.

After a sojourn in north-central Europe, this research now showed, Ukrainian-derived pastoralists from the steppe had entered India from the northwest during the Bronze Age, bringing the Indo-European languages with them. The notion that an Indo-Aryan invasion had brought the Vedic culture and its Sanskrit language to the banks of the Indus River, long rejected as a real mass-movement of people, was shockingly resurrected. To make matters even more uncomfortable, while the original Indo-Europeans, though light-skinned, appear to have been brown-eyed and brown-haired, the specific ancestors of the Vedic Aryans were a largely blond, light-eyed population, having picked these traits up after mixing with the Neolithic peoples of central Europe.

Across the world, there has been a recovery of older, more dynamic narratives of prehistoric movements. In East Africa, the founding tales of the coastal Swahili people, who trace their origins to Persian adventurers from the city of Shiraz, have been strikingly vindicated after long being dismissed as mere legend. In Britain, the traditional narratives of a huge population movement bringing over the ancestors of the Anglo-Saxons have now been confirmed beyond doubt. We can now trace the migrations of the Bantu peoples over Africa, the arrival of the modern Japanese in Japan, and even the definitive proof of pre-European contact between ancient Polynesia and the Americas. These are grand epics, etched in the hieroglyphics of our genes; stories of vast and often cataclysmic shifts spanning countless millennia, only now being unravelled. Yet, needless to say, the aDNA revolution has not been without controversy.

Kossinna Smiles

The findings of the aDNA revolution could scarcely have been calibrated to elicit more chaos or consternation in the archaeological mainstream. They most likely constitute the incipient stages of what Thomas Kuhn called a “shift of paradigms,” whereby an entire explanatory framework is exposed as inadequate and subsequently overturned. As Kuhn notes, the assimilation of new paradigms like these requires both the reconstruction of prior theory and the re-evaluation of prior facts in light of the new conception. Unsurprisingly, this process tends to provoke great displeasure among established academics, who immediately perceive the threat the new paradigm poses to their existing work.

The fluid, osmotic, ethnically ambiguous model of postwar archaeology is at least complicated, if not debunked, by the new findings from STEM. What has been recovered in its place—as the astute reader may have already noted—is a picture resembling an older, more worrisome archaeological consensus. The obvious implications of developments in aDNA research were pithily summarised in the title of a 2017 paper by archaeologist Volker Heyd: “Kossinna’s Smile.” An old, dusty door, long slammed shut, had been pried open, and a cold wind was seeping through. Although none of the new genetics literature mentioned the name “Kossinna,” nor terms like “culture-history” and “settlement archaeology,” it did not take long for the inference to be drawn.

Attempts to ward off readings with the smell of culture-history continue to this day. A 2025 anthology about the Northern European Neolithic includes this passage:

[One of the included papers] contemplates the influence genetic studies have had on the debate on the start and spread of the Neolithic, in some ways enabling a return to theoretically problematic culture-historical models. Instead, Thomas argues, we should explore the Early Neolithic of Britain as the coming together of a diverse set of people, things and practices which were different from what was left behind, with migration as a defining experience binding people into new social networks. [emphasis added]

The conclusion of these new findings, we are here assured, cannot possibly be anything upsetting to the prevailing narrative. Even its complete and express rebuttal will not suffice to rebuke it.

Other authors who are more clear-sighted about the damning implications of the new data have called for the imposition of implicitly censorious guidelines. In 2021, a paper was published titled, “Ethics of DNA research on human remains: five globally applicable guidelines.” Its authors introduce themselves as “a group of archaeologists, anthropologists, curators and geneticists representing diverse global communities and 31 countries.” Bizarrely, one of those authors is David Reich himself, and among the paper’s more reasonable statements is this striking assertion:

European archaeologists have worked for decades to deconstruct narratives that claim ownership of cultural heritage by specific groups. Ancient DNA research ethics in a West Eurasian context must follow this movement away from the use of self-identified notions of ancestral connections to certain land… [emphasis added]

The possibility that the new aDNA findings might simply constitute a refutation of the postwar archaeological consensus is not merely contested but categorically rejected—not on empirical grounds, but on the basis of ideology and fear. It cannot be true, it must not be true, evidence be damned.

In his paper linking the new aDNA findings to Kossinna’s theories, Volker Heyd refrains from calls for censorship. Instead, he chooses the route of obscurantism. “So, is it all that simple?” he asks rhetorically. “If [it is] that simple why have we archaeologists not seen these things much earlier?” Why indeed? Academics adore complexity. It is the signe par excellence of sophistication and in-group belonging to the highest circles of learning; a marker of the refined and expansive intellect. Brute simplicity, on the other hand, bears the stamp of vulgarity and the déclassé. In the elevated dialect of the university, “Is it really all that simple?” can only ever be understood as a disparaging question, the answer to which is invariably: “No, of course not!”

“Simple solutions for complex problems are never the best choice,” Heyd intones. He is either sophistically right or commonsensically wrong. Insofar as a problem is truly irreducibly complex, a simple solution obviously will not do—there is no single explanatory factor that will account for the launch of a space rocket. Nevertheless, an event or process may be, in its details and influencing factors, complex, whilst nonetheless forming a unified, coherent and, yes, simple overall narrative. Is it overly simple to say that the Norse language and the Dane axe were carried out of Scandinavia beneath the mast of the longship? Is it overly simple to say that the Spanish yoke was brought to the Aztecs and the Maya by caravels and muskets? Is it overly simple to say that the armies of one faith brought Arabic to the coasts of the Atlantic, and the armies of another battered down the gates of Jerusalem?

Sometimes, history is simple, however unsophisticated this may sound to the encultured academic. That does not mean, of course, that there was not a host of complicating variables which preceded, enabled, and modulated all these events. Simple does not mean simplistic. But it does mean that sometimes the ultimate answer to a grand historical process really does reduce to: “A certain group of men with large axes rode out and applied said axes to another group of less competently equipped men.”

For the committed devotee of the 20th-century archaeological paradigm, it is all rather like a sick twist at the end of a movie. Culture-history is dead, the wooden stake driven through its heart, and the old guard of archaeologists is readying for a pleasant retirement. Then, just as the screen is about to fade to black, the credits about to crawl, we see the revenant of Kossinna rising from the grave, a smile in his dead eyes. Is it not unbearable to think that this is where the credits should roll? Is it not too cruel to be the truth? Yet how did the name of Kossinna ever even return to the lips of the living? This point is worth dwelling on. In all likelihood, the geneticists who began the aDNA revolution had never even heard of Kossinna, nor his long-disgraced culture-history model, nor the beginnings of modern archaeology. His name does not appear in their papers, his ideas did not inform or influence their results or analyses. It was the archaeologists. the only people who even still remembered him, who drew the connection with his ideas and conjured him back.

The old proponents of the culture-history model and the modern, cutting-edge geneticists arrived at the same general picture of human dispersal and cultural turnover independently. To the disinterested observer, this ought to offer a compelling indication of the picture’s veracity. Only to the entrenched academic partisan will it appear as proof of the need for vigilance and mental athleticism, lest the forces of brute observation and deduction gain an advantage against the kingdom of motivated reasoning.

Conclusion

The pursuit of history can easily become an effort to recover a past, not as it was, but as we wish it had been. However much we may scorn the notion that the sins of the fathers should be visited “upon their children unto the third and fourth generation,” nevertheless we cannot quite shake the mode of thinking. The past seems to bear heavily upon the present—what has been will be, and there is nothing new under the sun. Whether this is in fact altogether true is another conversation. We may certainly hope it isn’t, as regards those events concerned in this article.

Yet whatever squeamishness, scruples, and unease we may harbour against the signs of an unedifying past, signs they remain, and it is the duty of the scientist and the historiographer to report it as he or she finds them. It should be obvious that any other disposition, which would reject a conclusion, not on the basis of its data or methodology, but merely because of certain perceived connotations, is one fundamentally at odds with the intellectual integrity and rigour demanded of a healthy academic life. Something is in fact either true or it is not: If it appears to be true, it is the duty of the honest scientist to report it; if it appears to be false, to reject it.

The scope of our investigations into prehistory have been greatly enlarged by the new tools of aDNA, and there is much to be gained by their employment in pursuit of knowledge and understanding. We are living in a time of great excitement, innovation, and discovery—for the ones, that is, who will accept and embrace it.

CORRECTIONS: An earlier banner image featured a portrait of Ivan Pavlov instead of Gustaf Kossinna. Also, the wording of the sentence about Kossinna and Maglemosian culture has been amended to better reflect the wording of the source. Quillette regrets these errors.