Art and Culture

The Art of Social Engineering

When British sculptor Thomas J Price explains that his “strategy of inclusion” will counter the “endless stream of limiting tropes and identities for Black people,” he is inadvertently mimicking totalitarian injunctions.

From the moment it was unveiled in Times Square in New York City on 29 April, British artist Thomas J Price’s 2025 sculpture Grounded in the Stars has been mired in controversy. The twelve-foot (3.65-metre) bronze depicts a nondescript black woman with braids and a Body Mass Index in the thirties range. Dressed in a T-shirt and trousers, she is posed with her hands placed insouciantly on her hips and a blank look in her eyes. “I hope Grounded in the Stars will instigate meaningful connections and bind intimate emotional states that allow for deeper reflection around the human condition and greater cultural diversity,” Price told Artnet back in February.

The statue has its defenders (the director of Times Square Arts told Artnet that Price’s work “imparts a sense of reverence for people’s everyday humanity”), but it has attracted a good deal of criticism and mockery from people of all races as well. As one account remarked below Times Square Arts’ Instagram post about the work, “This is some leftist nonsense just to piss off white people. And based on the comments, blacks don’t like it either.” A change.org petition opened by someone describing themselves as “a young Black woman” is demanding the statue’s immediate removal and a public apology. In a par-for-the-course reaction to the statue’s detractors, Alex Greenberger of ARTnews called their criticisms “deeply flawed” and “unnerving,” and he cautioned the art world to be vigilant.

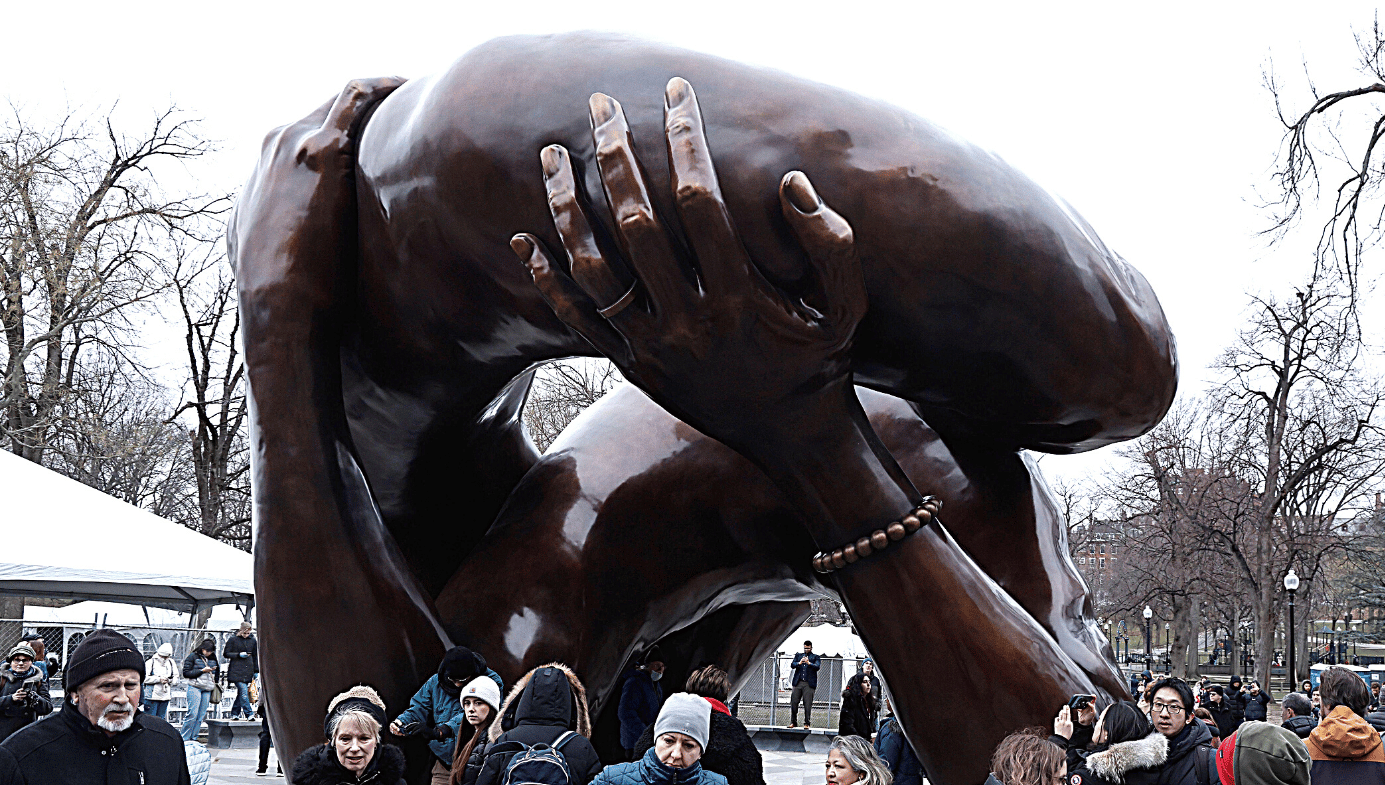

This row recalls the derision that greeted Hank Willis Thomas’s statue The Embrace when it was placed on Boston Common two years ago. Thomas’s sculpture purported to depict Martin Luther King, Jr. embracing his wife Coretta Scott King. It was so poorly rendered that Coretta’s cousin described it as “masturbatory,” while countless others pointed out the unintended genital and scatological resemblances. Still, at least Thomas’s work was an attempt to celebrate the life and legacy of a distinguished individual.

Price, on the other hand, has attempted to celebrate an “everyman” (or in this case an “everywoman”) by creating composites of anonymous models configured by digital sculpting. Grounded in the Stars is one of a series of six sculptures based on fictional identities. Hauser & Wirth is displaying the other five at its Wooster Street gallery in New York as part of a Price exhibition titled “Resilience Of Scale.” According to the H&W website, these “towering bronze figures” are intended to “amplify traditionally marginalised bodies and redress structures of hierarchy, inviting questions about who we chose to celebrate in art.”

Price shared his thoughts on public sculpture with Time magazine on 17 June 2020 after #BlackLivesMatter protesters in Bristol tore down a statue of slave trader Edward Colston and threw it into the city’s harbour. Statues, Price explained, “maintain the systems of power,” so tearing them down is not about “removing history,” it is about “creating a historical moment.” But simply replacing those statues with “alternative figures from history” would be misguided, he added, because it continues to “aggrandise particular individuals […] setting people apart.” His preferred solution was to erect public sculptures of anonymous composites that can counter the “endless stream of limiting tropes and identities for Black people.” The idea was to “critique the whole concept of portraiture. Portraiture is based on this idea of a person having the money to commission an artwork, or having done such great things that an artwork is commissioned in their honour.”

His work is, in other words, an exercise in a kind of jargony populist iconoclasm. Price’s only (stated) criterion is that his subjects must be black, because Price (who is also black) believes he can provide “a real insight to that experience.” This “strategy for inclusion” is meant to ensure “representations of those who have previously been stigmatised or invisible,” thereby helping to pave the way for a more cohesive society. Price’s artist profile on the Hauser & Wirth website pays lip service to “the intrinsic value of the individual,” but in Price’s model, the individual’s only function is to represent the identity group to which they belong, while the artist’s function is to challenge, confront, subvert, disrupt, and so on in an attempt to reshape society into an egalitarian utopia.

This kind of social-engineering agenda is not new to the arts, of course, and Price’s approach has some notable historical precedents. In the 1930s, it was practised on a nationwide scale in Soviet Russia, Nazi Germany, and, to an extent, in fascist Italy. In the USSR, this kind of agitprop was called Socialist Realism, the standards of which were unveiled in 1934 at the First Congress of Soviet Writers. The underlying ideological principle was elevation of the oppressed proletariat, in pursuit of which all art had to satisfy four requirements: