economics

In Defence of Neoliberalism

The neoliberal turn was a pragmatic response to failed economic intervention and yielded broadly positive results.

Many political scientists—from the conservative Patrick Deneen to the leftist Samuel Moyn—agree that the neoliberal turn, the shift toward more market-oriented economic policies during the 1980s and 1990s, was both sweeping and produced broadly negative results. But is this true?

According to the Fraser Institute’s Economic Freedom Index, the world’s economic freedom score has increased from 5.25 out of 10 in 1980 to 6.53 today. This is the result of shifts that have taken place in a number of countries, including the following examples:

- Chile: In 1973, socialist president Salvador Allende was deposed by General Augusto Pinochet in a military coup. While brutally socially repressive, Pinochet’s dictatorship was economically liberal, implementing sweeping market reforms. Guided by the Chicago Boys—free-market economists trained at the University of Chicago—Pinochet privatised many state-owned enterprises, liberalised international trade, and tightened government spending and the growth of the money supply.

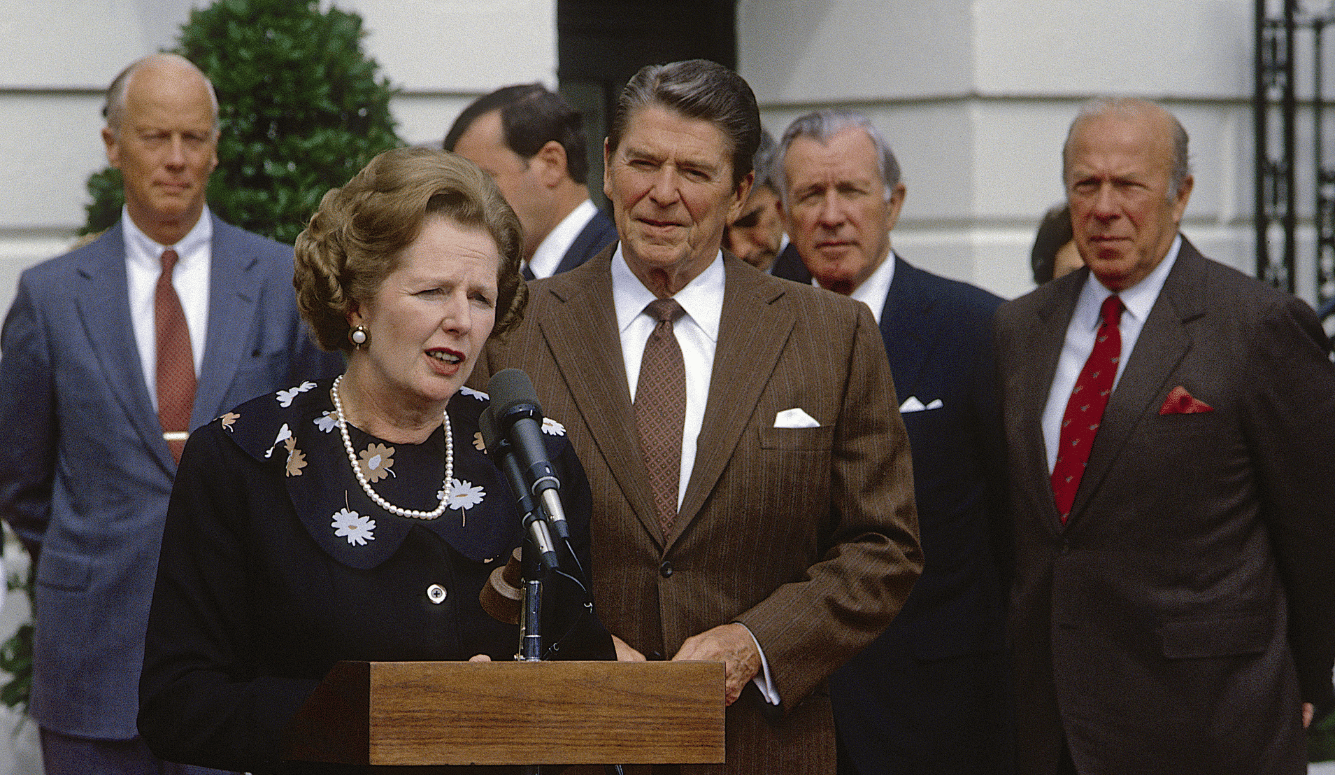

- Britain: Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government privatised state-owned industries, reduced the power of trade unions, cut taxes, and likewise tightened the growth of the money supply.

- China: Under Deng Xiaoping, China began privatising state-owned land and established free trade in special economic zones.

- United States: Ronald Reagan, an admirer and ally of Thatcher’s, ended oil price controls, deregulated certain sectors of the economy, and cut taxes. Meanwhile, Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker implemented monetary tightening to curb inflation.

- New Zealand: In the 1980s, a Labour government launched market reforms dubbed “Rogernomics” after Finance Minister Roger Douglas. These included dismantling state monopolies, deregulating financial markets, removing price controls, and privatising state-owned enterprises.

- The Soviet Bloc: The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 marked the beginning of the Soviet Union’s collapse and the onset of market-oriented economic reforms in its Eastern European satellite states.

- India: Facing a severe balance of payments crisis in 1991, Prime Minister P.V. Narasimha Rao and Finance Minister Manmohan Singh implemented sweeping reforms, including trade liberalisation, deregulation, and privatisation.

As these cases demonstrate, both right and left-wing governments in democratic and authoritarian regimes across the world embraced varying degrees of market reform within a relatively short period.

Neoliberalism emerged in response to the failures of state-centred economic policies. In the 1970s, the United States, New Zealand, and Britain struggled with double-digit inflation driven by Keynesian expansionary fiscal and monetary policies aimed at stimulating demand. Before the reforms inspired by the Chicago Boys, Chile faced hyperinflation of over 500 percent. Similarly, socialist economic planning in China, India, and the Soviet bloc resulted in pervasive inefficiencies and low material living standards compared to those of the Western world.

Neoliberal reforms produced broadly positive outcomes. Monetary tightening in the US, New Zealand, and Britain reduced inflation and delivered stable prices, albeit at the short-term cost of higher unemployment. In Chile, economic reforms, under first Pinochet and later the centre-left coalition Concertación (1990–2010), transformed the country from one of the poorer economies in Latin America to the second richest. Meanwhile, the partial transition of China and India from socialism to capitalism lifted billions out of extreme poverty.

The countries that moved most swiftly and comprehensively toward markets experienced the best outcomes. This is evident when we consider the divergent paths taken by the former Soviet Bloc states. Countries such as Poland, the Czech Republic, and the Baltic states, which embraced sweeping market liberalisation, experienced higher economic growth, lower inequality, and stronger democratisation. By contrast, nations like Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus—where liberal economic reforms were abandoned or pursued only partially—faced worse outcomes on all three fronts.

The challenges that neoliberalism arose to address—stagflation (the combination of high unemployment and high inflation) and the inefficiencies of state-controlled economies—have faded from view. Thus, anti-neoliberals are able to gloss over the failures of state-centred economic models and attribute the neoliberal turn to economic elites and international lending institutions like the IMF and World Bank.

This overlooks the fact that neoliberal reforms usually emerged domestically rather than through foreign imposition. For example, China’s market reforms were initiated in the late 1970s under Deng Xiaoping, despite the ruling Communist Party’s long-standing hostility to capitalism and its relative isolation from Western financial organisations. Like China, India was founded as an anti-colonial, anti-Western socialist state. But after decades of slow economic growth and a currency crisis, India embraced market reforms in 1991.

Critics of neoliberalism also argue that it has exacerbated inequality, led to financial instability, and fuelled the rise of populism. But while income inequality within some countries has increased, inequality between countries and around the world as a whole has declined since the 1990s due to rapid economic growth in previously poor nations. The rise of China, India, and other developing economies has contributed to a historic reduction in global inequality.

Neoliberalism is also frequently blamed for financial instability. Critics cite crises such as the 1997 Asian financial crisis and the 2008 recession as evidence of its failures. However, these crises were not inevitable consequences of market liberalisation. Instead, they were exacerbated by government policies that distorted financial markets. The Asian financial crisis, for instance, was fuelled by fixed exchange rate regimes that created unsustainable imbalances, while the 2008 crisis was driven in part by government-sponsored mortgage entities and artificially low interest rates set by central banks.

Finally, some argue that neoliberalism has fuelled the rise of populism in the United States by leaving large segments of the population and the country behind economically. But populism cannot be explained solely by economic factors. The US has outperformed most developed nations in economic growth and job creation over the past few decades. The rise of populism here is as much about cultural anxieties—such as immigration and national identity—as it is about economic grievances.

The world currently seems to be moving away from liberalism. The US is erecting trade barriers, China is expanding state control over the economy at the expense of private enterprise, and populist parties are gaining ground across Europe. Global democracy has been in decline for over a decade.

Yet history teaches us that liberalism has more staying power than we might fear. The interwar years saw the rise of fascism and communism together with the Great Depression, while the 1970s marked the height of state-led economic planning and intervention. But both eras eventually gave way to a revival of free markets, trade, and democracy. Whatever the short- to medium-term future holds, the core principles of liberalism—free enterprise, open markets, and responsible fiscal and monetary policies—have consistently proved successful and resilient.