Science

When Do Scholarly Retractions Become a Form of Censorship?

Focusing on the handful of papers that are retracted for political reasons can obscure the more important problems afflicting the field of academic publishing.

Adam Marcus and I co-founded Retraction Watch in 2010. We operate under the auspices of the Center for Scientific Integrity, a US-based non-profit organisation we co-founded in 2014. Our motto is, “Tracking retractions as a window into the scientific process.”

When it comes to academic publishing, which is a core field we monitor, a retraction represents an episode in which a paper is designated by its publisher as being so flawed that the conclusions can’t be relied upon.

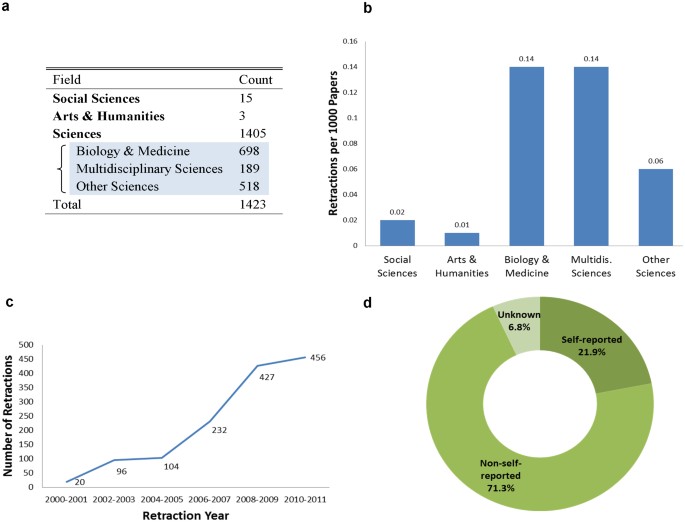

About two-thirds of the time, retractions arise from academic misconduct, which is why they are viewed as stigmatic among researchers.

There are now approximately 58,000 retractions in the Retraction Watch database—the vast majority of which, it is important to add, aren’t connected with the kind of ideological controversies that tend to be prominently reported in the lay press. Also important to note: About two-thirds of the time, retractions arise from academic misconduct, which is why they are viewed as stigmatic among researchers.

Sometimes, the timing of a retraction can raise suspicions of ideological interference. Critics of the decision to retract will argue that the stated basis for retraction is a mask for politicised motives, and that some papers are held to different standards based on their claims.

In 2024, we reported on the case of the journal Health Services Research and Managerial Epidemiology and its publisher retracting three papers about abortion—including one cited by litigants who opposed regulatory approval of mifepristone, an ingredient in what is commonly described as “abortion pills.” The complaints regarding the papers centred on allegations that data was presented in a misleading way, and that authors had conflicts of interest.

Some of these concerns were legitimate, in my view. However, it is true that nobody had prominently raised such concerns until the studies in question were seen as politically important. Did the independent reviewer who’d recommended retraction apply different standards to the papers as a result of these factors? That’s an open question, although I would lean toward “yes.” But it seems more than likely that such a review wouldn’t have taken place in the first place had it not been for the litigation. (And the authors have now sued the publisher over the retractions.)

Sticking with the abortion subject: In 2022, we reported on the retraction of a Frontiers in Psychology article that critiqued The Turnaway Study, which is a prospective longitudinal examination of women who’d failed to receive sought-after abortions. The retraction followed expressed concerns that the journal’s peer-review process hadn’t been objective. Specifically, the editor and all four reviewers (whose names, it should be said, the journal had prominently disclosed) were affiliated with anti-abortion groups.

Even more so than in the case involving Health Services Research and Managerial Epidemiology, the problems with the retracted papers were described as merely procedural in nature. But critics of the decision to retract viewed it as a manoeuvre intended to support the case for wider access to abortion services.

In some cases, critics allege, calls for retraction rise to the level of “mobbing.” It’s a term I don’t like to use—although it should be said that in rare and extreme cases, publishers truly are targeted with intimidation campaigns. This was the case in 2017, when Third World Quarterly published “The Case for Colonialism,” by Bruce Gilley, a professor of political science at Portland State University. That article argued—to quote the abstract—that “Western colonialism was, as a general rule, both objectively beneficial and subjectively legitimate in most of the places where it was found, using realistic measures of those concepts.” If you go to the link where the article once appeared, you will find this notice:

This Viewpoint essay has been withdrawn at the request of the academic journal editor, and in agreement with the author of the essay. Following a number of complaints, [we] conducted a thorough investigation into the peer-review process on this article. Whilst this clearly demonstrated the essay had undergone double-blind peer review, in line with the journal’s editorial policy, the journal editor has subsequently received serious and credible threats of personal violence. These threats are linked to the publication of this essay. As the publisher, we must take this seriously. [We have] a strong and supportive duty of care to all our academic editorial teams, and this is why we are withdrawing this essay.

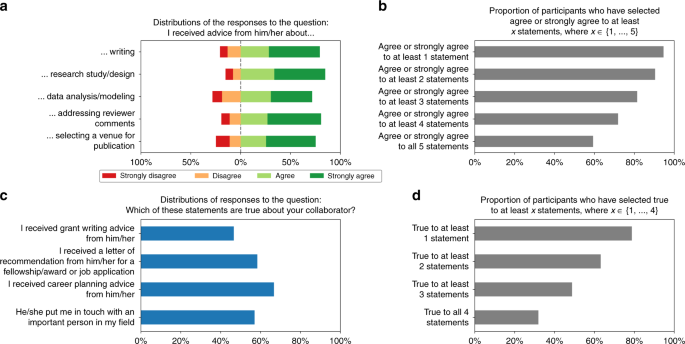

Some authors acquiesce to the retraction of their own work following ideologically charged complaints. This was the case with a 2020 article in Nature Communications that claimed women in science fare better, on average, when they have male mentors as compared to female mentors. The article’s conclusions were seen as very much offside the popular progressive consensus, and attracted online criticism.

In an editorial note concerning the controversy, the editors wrote that these events “led us to reflect on our editorial processes and strengthened our determination in supporting diversity, equity and inclusion in research.” The authors, for their part, used the retraction notice to tell readers they have an “unwavering commitment to gender equity.”

But in their editorial note, the editors also sought to distance themselves from the suggestion that they were bowing to politicised pressures. They wrote that “simply being uncomfortable with the conclusions of a published paper… should not lead to retraction on this basis alone”; and argued that the paper in question had methodological problems, such as the embedded assumption that co-authorship of published papers by junior female scientists with more senior co-authors could be used as a proxy for mentorship.

Then there’s the case of the late psychologist Richard Lynn (1930–2023), who was stripped of his emeritus status at Ulster University in 2018 following publication of an article entitled “Reflections on Sixty-Eight Years of Research on Race and Intelligence” in the MDPI journal Psych. Last year, a 2010 article based on his data, “Parasite Prevalence and the Worldwide Distribution of Cognitive Ability,” was retracted by Proceedings of the Royal Society B. The article argued that

the worldwide distribution of cognitive ability is determined in part by variation in the intensity of infectious diseases. From an energetics standpoint, a developing human will have difficulty building a brain and fighting off infectious diseases at the same time, as both are very metabolically costly tasks.

This is an example of a case where the act of retraction creates knock-on effects, with increased scrutiny applied to articles that either cited, or were cited by, the retracted scholarship. Authors of such works will sometimes present caveats about their own work as an apparent pre-emptive effort to prevent guilt by association. Following the aforementioned retraction of Lynn’s article, a Canadian researcher in the field responded by telling Retraction Watch that his own research now should be marked with a “public health warning.”

Obviously, the threat of ideologically motivated retraction campaigns is real. And sometimes, you even see authors take the initiative by asking to have their articles retracted after they observe that they are being cited in support of unfashionable conclusions. This was the case with a 2019 article in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that found “no evidence of anti-Black or anti-Hispanic disparities across shootings, and White officers are not more likely to shoot minority civilians than non-White officers.”

Those authors, it should be noted, later backtracked somewhat, saying that their move was not because of “mob pressure” or “distaste for the political views of people citing the work approvingly.” They also acknowledged having been “careless when describing the inferences that could be made from our data.”

Journals occasionally make similar moves. In 2017, the New England Journal of Medicine added an editor’s note to a decades-old letter that had been used—or, as they argued, misused—by opioid makers to promote usage of painkillers. Notably, they did not make any claims that the letter—which was very limited in scope—was wrong.

On the other hand, culture-war critics often claim “censorship” when there’s credible evidence that a retracted paper is just flat out wrong. One example here is the work of Peter McCullough, a cardiologist at the Institute of Pure and Applied Knowledge, who was decertified after the American Board of Internal Medicine determined that he’d “provided false or inaccurate medical information to the public”—including the false claim that up to 50,000 Americans may have died due to COVID-19 vaccines in the first six months of 2021 alone.

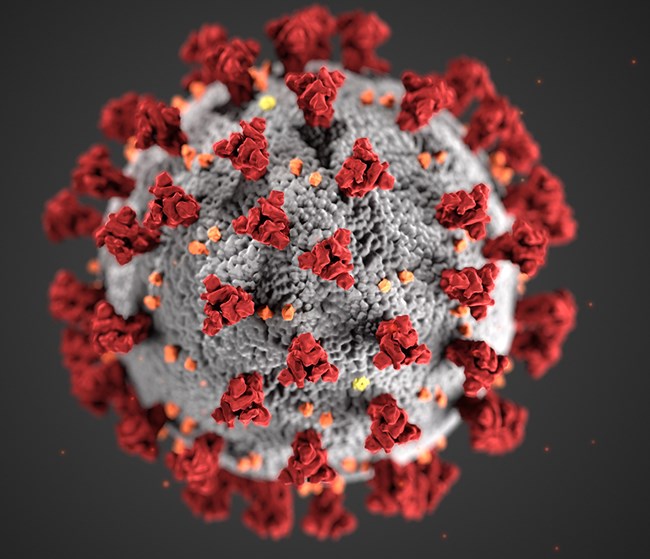

McCullough’s name appears on several COVID-related articles that have been retracted. The most recent retraction came this past January, in regard to a Future Microbiology article entitled, “Effectiveness of Ivermectin-Based Multidrug Therapy in Severely Hypoxic, Ambulatory COVID-19 Patients.” The study purported to demonstrate that ivermectin-based treatments provide a “practical, inexpensive, safe, readily available and highly effective… routine treatment for outpatient COVID-19.” The editors wrote that “upon review of all materials, we were unable to confirm the integrity of the study design and the reported findings. Therefore, the editorial team no longer has confidence in the reported conclusions and has decided to retract the article.” I would not say that this amounts to “censorship,” despite the claims of McCullough’s defenders.

Unfortunately, McCullough is not alone. The authors of an article published in Public Understanding of Science, relying on our tally of more than 500 retractions of COVID-19-related papers, note that the works in question “were either retracted from publication or withdrawn from preprint servers due to serious research or publishing errors.” As the authors observed, “by violating research norms, many of these articles were able to fabricate novel or controversial findings that received more academic citations and media attention than non-retracted COVID-19 research.”

Alas, retractions and article withdrawals don’t always serve to reduce the influence of the underlying conclusions. The Public Understanding of Science authors give the example of a 2021 medRvix preprint that falsely claimed COVID-19 vaccines would cause acute heart disease in one out of every 1,000 vaccinations. When the authors discovered their mathematical analysis had been obviously flawed, they withdrew the article and apologised. Despite this, the incorrect claim was repeated to twenty million listeners on a Joe Rogan podcast. On social media, meanwhile, some conspiracy theorists claimed the episode was evidence that authorities were seeking to censor the truth about COVID-19.

The Public Understanding of Science authors performed a content analysis of social-media posts in regard to two well-known retracted COVID-19 articles. And the results were telling.

The first retracted article—published in Lancet in 2020—emphasised the harms caused by hydroxychloroquine, whose supposed benefits as a COVID-19 treatment had been promoted by Donald Trump. When the article was retracted due to evidence of data fabrication (or, as the retraction notice put it, “because the veracity of the data underlying this observational study could not be assured by the study authors”), vocal conspiracists claimed that this showed the article’s original publication had been a politicised effort to malign both hydroxychloroquine and Trump.

The second retracted article studied by the Public Understanding of Science authors, which had been published in Current Problems in Cardiology, emphasised the harms caused by COVID-19 vaccines. But in this case, the retraction was either ignored on social media, or it was taken as evidence of an attempt to suppress the anti-vaccine claims made in the retracted paper (which, naturally, had already been widely shared by vaccine opponents anyway).

In other words, it didn’t matter whether the retracted article supported or opposed the preferred narrative put forward by dissident critics of the medical establishment. In both cases, the narrative was selectively understood to constitute evidence that heterodox medical information was being suppressed.

Another problem is that many scholars continue to cite papers even after they are retracted—typically “to bolster arguments or use methodologies without acknowledging their status,” as two scholars studying the problem concluded.

In 2023, about 0.2 percent of published papers were retracted, up from just 0.02 percent in 2002. But my own view is that the rate of retraction at scientific publications should be much higher—probably something closer to ten times the current rate. Even if some papers are being improperly targeted for ideological reasons, the larger problem lies with the much greater number of papers that should be retracted (for reasons that have nothing to do with ideology or politics), but aren’t.

And there are all sorts of reasons why the retraction rate remains (as I see it) artificially low. Journals often drag their feet for years on complaints about papers, even when those complaints come from well-established scientists offering clearly documented analyses. And authors have abundant reasons to vigorously resist having their work retracted. One 2013 study found that, as the abstract summarised it, “a single retraction triggers citation losses through an author’s prior body of work. Compared to closely-matched control papers, citations fall by an average of 6.9% per year for each prior publication.”

What was particularly noteworthy about this study was that “citation losses among prior work disappear when authors self-report the error.” In other words, when researchers go out of their way to correct the record, they don’t suffer a “retraction penalty.” This suggests there is an incentive to do the right thing.

Another problem is that the amateur sleuths and institutional whistleblowers who come forward with information about problematic articles—the sort of disclosures that often spark an investigation that can lead to retraction—are increasingly facing threats of professional repercussions and legal retaliation. If you’re going to make a case that anyone is being “censored,” in fact, I’d argue that it’s these whistleblowers who have the strongest case.

Overall, I’d like to see more humility from academics. It should be acceptable for authors to say, “I was wrong. I admit it.” As we’ve chronicled at Retraction Watch, some scientists have done just that. Insofar as such admissions stem from honest errors, it doesn’t mean they’re bad scientists, much less that they’re acting under the effects of ideologically imposed duress or censorship. It simply reflects the reality that scientists are human, and humans make mistakes. The scientific enterprise can only profit when we encourage those mistakes to be publicly flagged in a timely fashion.

This essay was adapted from a keynote lecture delivered by the author at Censorship in the Sciences: Interdisciplinary Perspectives, a conference hosted by the Center for Economic and Social Research at the University of Southern California’s Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences in Los Angeles.

Editor’s note: Due to an editing error, the originally published version of this essay incorrectly identified the author of “Parasite Prevalence and the Worldwide Distribution of Cognitive Ability” as Richard Lynn. The text has been corrected to indicate that the 2010 Proceedings of the Royal Society B article was authored by Christopher Eppig, Corey L. Fincher, and Randy Thornhill.