Politics

What’s So Terrible About Trade Deficits Anyway?

Populist rhetoric and the hidden costs of economic illiteracy.

In under a week, the US president lurched from announcing sweeping global tariffs and insisting he’d never back down to backing down entirely—at least for ninety days (in most cases)—and claiming that other countries had grovelled to him for mercy. In ninety days’ time, the world may be looking at the same tariffs, completely new ones, or none at all. Stable economics this is not.

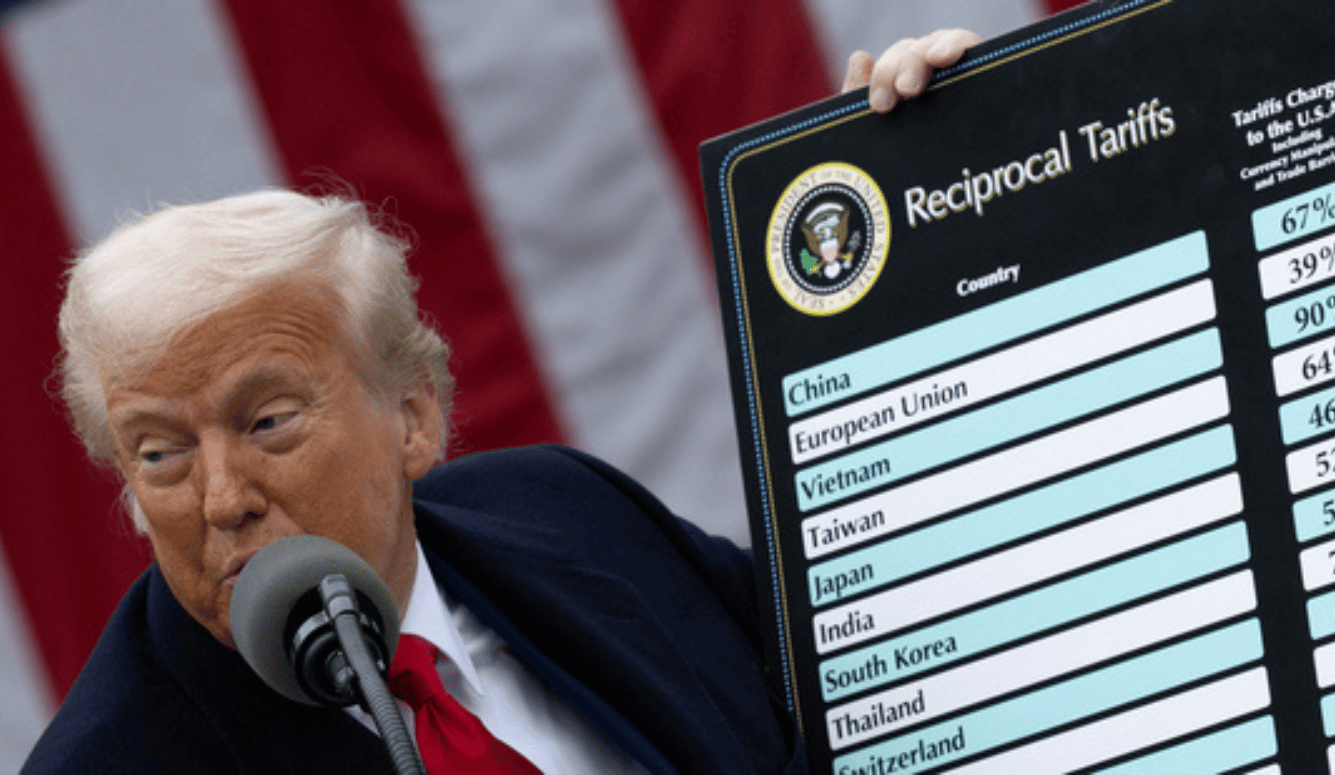

When the tariffs were originally announced, the justification—that these were only reciprocal tariffs, and in some cases even more generous than that—did not sound unreasonable on its face. Yet what Trump and his team deemed reciprocal actually meant a ten percent baseline, some reciprocity here and there, and an unintelligible calculation ostensibly intended to iron out trade deficits via punitive tariffs elsewhere. The last of these measures attempts to ensure that the US exports as much as it imports from every country.

Trump reasoned against trade deficits in characteristically dramatic manner: other countries are treating the US unfairly, taking advantage of Americans, it’s been going on for too long, and he will be the one to finally put a stop to it. It is not clear whether Trump’s hatred of trade deficits—a position he has reportedly held for decades—is a considered economic view, or just another populist impulse masquerading as policy. But a brief investigation into what trade deficits are suggests that his anger is unreasonable.

Let’s consider the example of Vietnam for a moment. Vietnam—like many Southeast Asian countries—drew one of the higher tariffs in Trump’s plans. Vietnamese goods were threatened with tariffs as high as 46 percent when they arrive in the US (paid by US importers), yet the highest tariffs that Vietnam levies on US goods are 9.4 percent, and 17.1 percent for agriculture. The US already tariffs Vietnamese goods at approximately four percent in return.

So, should the US at least raise its tariffs to 9.4 percent, to match Vietnam reciprocally? Successive US administrations have not done so for at least three good reasons:

- Politics: Vietnam remains geopolitically torn between the US and China. Alienating them risks pushing them into China’s orbit.

- Costs: Higher tariffs increase prices for US consumers.

- Economics: Vietnam exports key inputs like electrical machinery and plastics to the US. Tariffs on these drive up the costs of doing business in America.

However, the notion that the US should exceed reciprocal tariffs to level out the trade deficit with a country like Vietnam is bizarre. The US has a nominal GDP per capita of around US$82,769; Vietnam has around 1/20th of that wealth, with a nominal GDP per capita of US$4,282. If a country has 1/20th of the wealth of another, then it will have roughly 1/20th of the capital available to buy goods from the other. And yet, the US trade deficit with Vietnam in 2024 was about US$123.5 billion. If the two countries had a proportional relationship, that trade deficit would be US$248.9 billion.

In other words, Vietnam is spending proportionally more of its cash on US goods than the US spend on theirs. It makes neither rational nor moral sense for a large and wealthy country like the US to tax a small, poorer country’s exports simply because that country spends less on US goods. Bankrupting Vietnam or discouraging it from trading with the US at all is going to be bad for the US economy—a net loss that cannot easily be replaced.

What about more wealthy countries or blocs like the EU? Is the Trump administration not right to tariff EU goods and pursue trade parity? Before Trump’s “liberation day,” the EU tariffed US goods at 4.8 percent on average and the US tariffed EU goods at approximately 1.2 percent. The US threatened to impose a twenty percent tariff on EU goods, primarily to correct for the trade deficit.

In 2024, the EU surplus with the US (i.e., the total it exported to the US less the total it imported from the US) was €198.2 billion, leaving the US with a roughly 37 percent trade deficit. But not every country in the EU is as wealthy as France and Germany—broadly speaking, the EU should have 46 percent less capital to spend than the US due to its lower GDP per capita, but the trade deficit is only 37 percent. That means the US has a real-world surplus of nine percent.

There is no moral or rational basis for claiming that the EU is exploiting the US. Like Vietnam, the EU goes over and above what should be expected in terms of US imports, and there is no reason to suggest that there is any extra US importing capacity they could muster in order to eliminate the trade deficit. A rich country must accept that poorer countries or blocs will almost certainly buy fewer goods than richer nations, simply because they have less capital with which to do so. Indeed, these examples show that the US has lower trade deficits than would be expected from the available capital in the economies with which it is trading.

But, what if US trade deficits were the same as expected or higher? Would that justify the use of aggressive tariffs? Well, no, not really. The world is not a perfect place, and trade relationships fluctuate over time, particularly as one country or another outperforms expectations, or benefits from specific advances in particular companies or industries. Whether you are the world’s largest economy, the world’s most average, or one of the world’s smaller economies, you will have trade relationships with multiple countries. The amount of surplus or deficit—as defined as a proportion of GDP—will tend to average out so long as a country is in that average level of performance. It will outperform with some trade partners, underperform with others, and all of it will likely change over time. It’s a part of the global cycle: you’re always going to have a trade deficit with someone. And if you want surpluses with others, you have to accept that.

Trump’s grand plan is meant to achieve one of two things: relocate companies to the US in order to help them avoid the tariffs, or reduce importing to the US in order to boost domestic companies instead. The goal in either case is improved GDP (by swallowing large companies from elsewhere, or US companies selling more to US customers).

The former is largely a moot point, despite it being Trump’s most vocal reasoning behind the trade-deficit arguments. Yes, a large multinational company can decide to relocate to a large market like the US. But it isn’t cost-effective, particularly not if the countries with which the US trades have had to raise tariffs on that company’s products because of tariffs the US has imposed on theirs. It means the company is moving to the US just to service US consumers, which is far less attractive and will require a needless extra cost of a new business site.

This is unlikely to happen now anyway because Trump’s plan has changed from day to day, with tariffs announced one moment, paused for ninety days the next, and he keeps saying he’s willing to renegotiate them. No company is going to spend billions of dollars and years of planning to relocate to the US based on tariffs, when they don’t know what new plans the US is going to announce in two weeks, let alone in five years when an entirely new president will be in office.

Besides which, most of the global economy still operates through small companies that simply don’t have the ability to relocate. Many of those companies will also have patents, expertise, and trademarks, and it may not be possible or economically viable to produce their products in the US directly. The only outcome of trade-deficit linked tariffs will be higher prices of these goods in the US, or locking them out of the US market, meaning US consumers can’t buy and benefit from them.

Any remotely economically minded person knows this. So, the most likely aim of Trump’s attacks on trade deficits is increasing US exports. Yet, given the US already over-performs in relation to expectations based around GDP, who is it going to increase exports to?

The answer is: to the developing world. All those nations in Africa, Latin America, or Asia, perhaps, that are on the verge of becoming really useful trade partners full of people patiently waiting to become global workers and global consumers. In the mid-20th century, the US spent billions of dollars on developing countries such as Japan and South Korea, and now massively benefits from these economies. This aid has turned out to be an extremely sound business-development technique that has created hundreds of millions of consumers for American companies (as well as suppliers for American businesses). But as Trump’s DOGE has now drastically reduced USAID, that will likely not happen in the next fifty years.

What’s more, the imposition of punitive tariffs on poorer countries like Vietnam will simply impoverish rather than improve the potential importing power of these countries. Disrupting the economic development of poorer countries isn’t going to improve the chances of selling to them.

The irony is brutal. Trump’s fixation with trade-deficit “offenders” is punishing the very nations that could one day erase those deficits through development and prosperity. US consumers, businesses, and economic growth will all suffer as a result of the US president’s inability to grasp this elementary logic. There seems to be just one long-term strategy behind all this: unleash populism for immediate electoral returns, blame someone else for the problems that populism inevitably causes, and let someone else deal with the long-term consequences.