Ancient History

Nicholas II, Aššurbanipal, and Marco Polo Walk into a Bookstore…

Quillette editor Jonathan Kay reviews three newly published history books about the Assyrian Empire, the fall of the Romanovs, and the travels of Marco Polo.

Tsar Nicholas II, being the last reigning Emperor of Russia, ranks as a major historical figure. Yet in many histories of the 1917 Russian Revolution, the Tsar is treated almost as a secondary character—more a passive symbol of old-world aristocracy than a major protagonist in his own right. This is why I was uncertain about launching myself into historian Tsuyoshi Hasegawa’s newly published book, The Last Tsar: The Abdication of Nicholas II and the Fall of the Romanovs. As despotic and bloodthirsty as Vladimir Lenin and his fellow Bolshevik revolutionaries proved to be, they were decisive figures who bent history to their will. By comparison, Nicholas II struck me as torpid and dull.

Reading The Last Tsar only reinforced this impression. Hasegawa’s expert description of Nicholas II’s last years also raises the question of whether a more enlightened and competent Imperial leader (such as, say, his first cousin once removed, Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaevich) might have managed to hold Russia together long enough for it to make the transition to a liberal constitutional monarchy.

In the Russian tradition, Tsars were idealised as divinely ordained autocrats in the absolutist feudal tradition. It was a thoroughly antiquated conceit, but one that Nicholas II embraced wholeheartedly, assuring more liberal-minded critics within his own family that he would “devote all my strength to maintain, for the good of the whole nation, the principle of absolute autocracy, as firmly and as strongly as did my late lamented father [the reactionary Alexander III].” Much like Charles I of England three centuries earlier, he was a believing Christian who truly imagined himself to be God’s chosen leader.

Unfortunately, Nicholas didn’t have the strength of character required of a national leader, as became tragicomically evident once he declared himself Russia’s commander-in-chief during World War I: When the Tsar showed up at military headquarters to assume “command,” his own generals relegated the aristocrat to ceremonial and back-office functions.

To describe Nicholas II as out of touch with Russia’s soldiers, peasants, and urban proletariat during this time of crisis would be an understatement. While (literally) millions of Russian men were dying at the front, his diary entries were dominated by lists of people he’d lunched with, and amusements he’d undertaken with his family. In one letter to his wife that he wrote from the Russian war room, he spoke vaguely of “big maps… full of blue & red lines, numbers, dates, etc,” like a schoolboy on a field trip to a military museum. At the height of a key campaign, Russia’s massive summer 1916 offensive in Galicia, Nicholas II was holed up reading a soppy children’s tale called The Story of Little Boy Blue. By the time Nicholas was forced to step down in early 1917, several of his own Romanov relatives were predicting (accurately) that his incompetence would invite violent revolution.

It’s rare to read a biographical work whose author is so contemptuous of his subject as Hasegawa is of Nicholas. And yet the author, a specialist on 20th-century Russian history, seems even more ill-disposed toward the Tsar’s wife, Alexandra Feodorovna (born Princess Alix of Hesse), whose surviving letters to Nicholas are full of terrible political advice, parochial attacks on their perceived enemies, and hectoring demands that he more ruthlessly embrace his role as autocrat. Much of her counsel wasn’t even her own: Often she was just parroting opinions from Grigori Rasputin, the debauched mystic who’d gained the royal couple’s favour by presenting himself as a miraculous faith healer who could help their hemophiliac son, Alexei.

It’s rare to read a biographical work whose author is so contemptuous of his subject as Hasegawa is of Nicholas.

Before reading The Last Tsar, I hadn’t fully appreciated the full fanatical extent of Alexandra’s dedication to Rasputin, nor the degree to which his influence on affairs of state had caused the royals to become mocked and reviled by fellow nobles. (In one letter to her husband, she wrote: “Oh, my dear, I pray to God so passionately to convince you that in Him [Rasputin] lies our salvation. If He weren’t here, I don’t know what would become of us. He is saving us with His prayers and His wise advice.”) Amazingly, even after Rasputin was murdered in late 1916, the Tsar and his wife simply transferred their mystical allegiances to Rasputin’s acolytes—including a mentally unstable occultist named Alexander Protopopov, whom Nicholas propped up as Interior Minister till the end of his reign.

Nicholas II’s story ends in July 1918, with the cold-blooded slaughter of his entire family by Bolshevik agents—including five children, several of whom were bayonetted after watching their parents shot to death. Ineffectual, gullible, and imperious as Nicholas and his wife may have been, they did not deserve to die like this. Nor did the millions of other Russians who were exterminated (or worked to death in gulags) by the communist regime that would transform the Tsar’s decrepit autocracy into a full-fledged totalitarian dystopia.

No doubt, many Russians imagined that whatever replaced Romanov rule could not possibly be worse. Tragically, they were very much mistaken.

If you’re a fan of ancient history, I heartily recommend the Lost Civilizations series published by the University of Chicago Press through its Reaktion Books imprint, which I first encountered via Frances F. Berdan’s outstanding 2021 volume on the Aztecs. The latest entry is The Assyrians, by British Museum Mesopotamia expert Paul Collins (who also wrote the Sumerian entry back in 2021). Like other books in this series, it’s a quick read, compressing many centuries of history into a volume that I was recently able to consume cover-to-cover during a single four-hour plane trip from California to Toronto.

The Assyrian empire existed in some form for a period of about 1,400 years, from its origins as a city-state in the northern part of modern Iraq in the 21st century BC, to its (shockingly precipitous) demise in the late seventh century BC. At the height of Assyrian power, this was the largest empire the world had ever witnessed, extending from Egypt into the Levant and the Anatolian plateau, and east through the ancient cities of Aleppo, Nineveh, Assur, Babylon, Uruk, and Susa. Many centuries before the Romans brought the Mediterranean world under the Pax Romana, Mesopotamian merchants ran donkey-powered caravan networks from the Nile to Persia’s Zagros Mountains under the protection (and taxing power) of Assyrian rulers and their local proxies. The wealth fuelled the construction of cities whose size and grandeur put any of Europe’s fledgling Iron Age counterparts to shame.

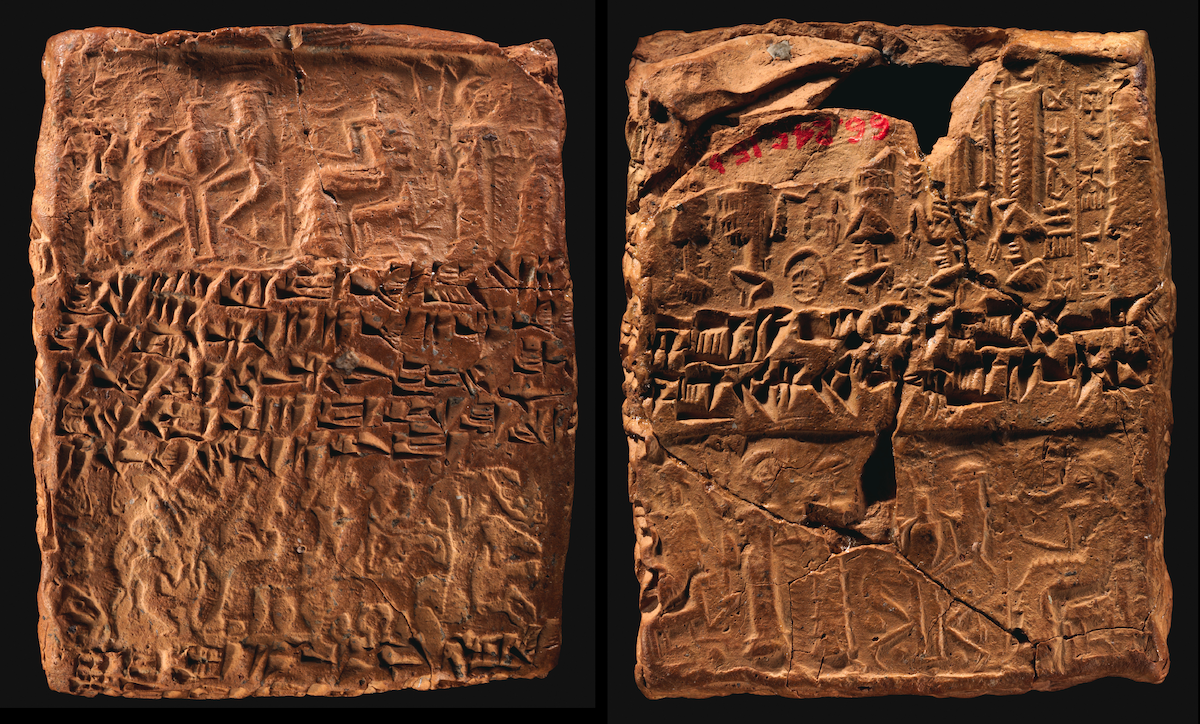

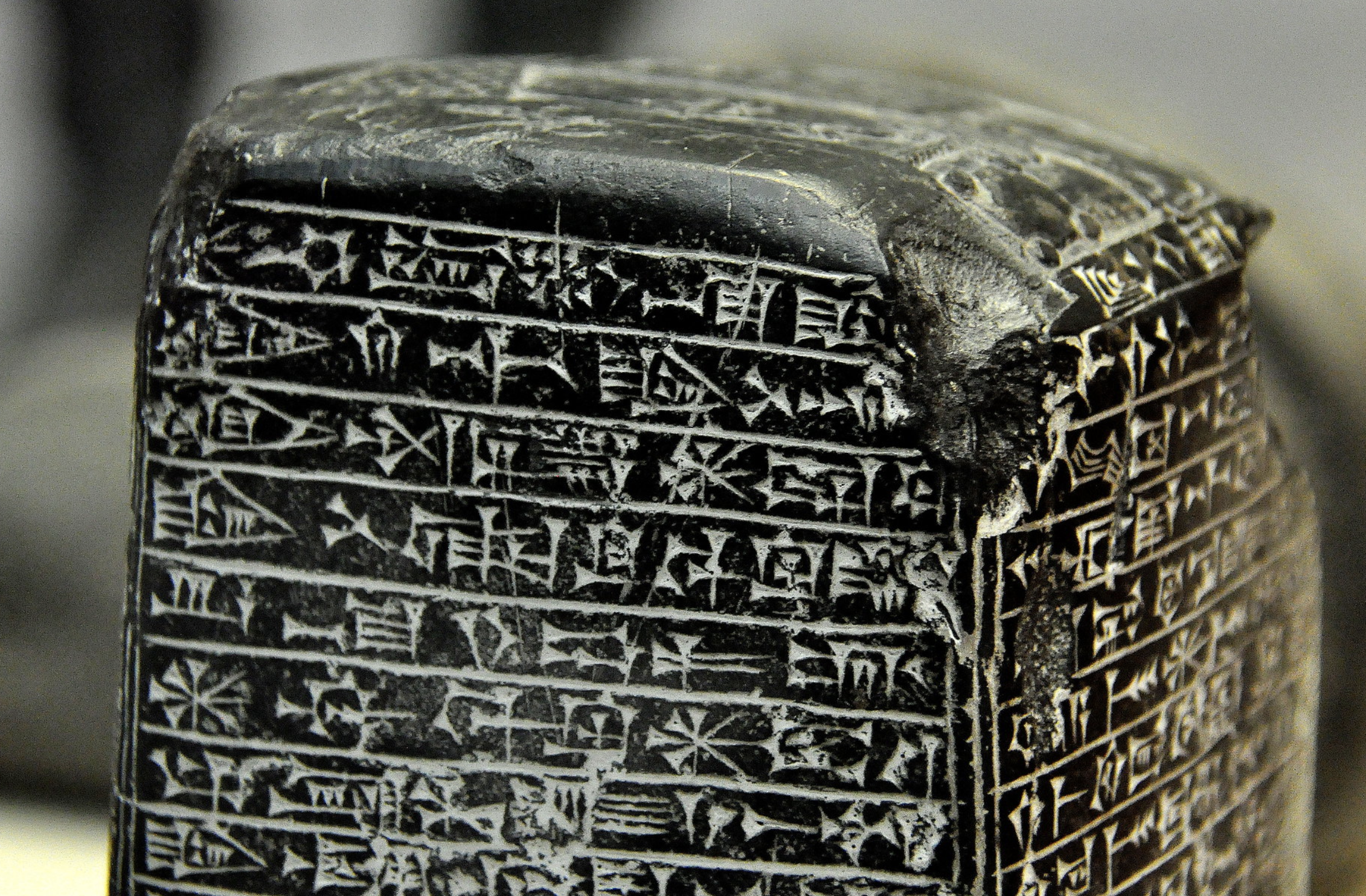

Like their counterparts in other ancient Mesopotamian societies, Assyrian elites were literate, and left modern historians with a rich trove of written artefacts. These include not only formal stone inscriptions and artwork found on surviving temples and other public works, but also mundane public records stamped into clay tablets using the logo-syllabic writing system known to us as cuneiform.

One surviving 3,900-year-old set of tablets found at the site of an Assyrian trading post in modern Turkey, for instance, records the conflicting testimony of two merchants, one of whom claims to have had his goods stolen by the other. “In spite of the fact that you had no claim on either me or my agent Idi-Ishtar… you high-handedly entered [Idi-Ishtar’s] house and you robbed the strongroom,” one complains. “Ever since then, I have been chasing you… After all this, you go on asking me questions in court concerning my [former statements recorded on] tablets!”

Surviving inscriptions also teach us much about Assyrian supernatural mythology, a polytheistic system based around four main gods—Aššur (formerly a regional deity associated with Assur, the original Assyrian city-state), Anu, Enlil, and Enki. Collins doesn’t provide a systematic overview of Assyrian supernatural beliefs, but does describe a number of their fascinating idiosyncrasies, including this one: When court priests concluded that the Assyrian king was about to be attacked by one or more gods, they’d send the king into hiding, and recruit a commoner to play the role of fake king. This faux-monarch would dress and act as if he were truly ruling the country—the odd conceit being that while the gods were powerful enough to strike down any man they pleased, they were also so utterly clueless that they couldn’t tell one man from the next if they dressed and acted alike.

In a morbid denouement, the fake king would then make a great show of reciting out loud all of the crimes and evils that the real king had committed (and which were believed to have attracted the gods’ ire in the first place). And then a funeral would be conducted for the fake king so that the gods might imagine that there was no need for divine regicide, as the object of their anger had already been dispatched.

There are also numerous surviving tablets containing correspondence between Assyrian rulers and their neighbours, which have helped historians understand the region’s (often fantastically complex) geopolitics; as well as produce detailed genealogies of most of Assyria’s 117-odd kings.

A major theme in these documents is a fixation on status and opulence. Certainly, rulers from this period weren’t shy about pestering one another for gifts and tribute, as in this excerpt from a (somewhat petulant) letter sent by the then-upstart Assyrian ruler Assur-uballit (1356–1322 BC) to his Egyptian pharonic counterpart (thought to be Amenhotep IV):

I send as your greeting-gift a beautiful royal chariot outfitted for me, and two white horses, [another] chariot not outfitted, and one seal of genuine lapis lazuli. Is such a present [not fit for] a great king? Gold in your country is dirt; one simply gathers it up. Why are you so sparing of it? I am engaged in building a new palace. Send me as much gold as is needed for its adornment. When Asur-nadin-ahhe, my ancestor, wrote to Egypt, 20 talents of gold were sent to him… Now I am the equal of [such kings], but you sent me [illegible cuneiform markings], and it is not [even] enough for the pay of my messengers on the journey to and back. If your purpose is graciously one of friendship, send me much gold.

Other surviving writings from ancient Assyria relate to that age-old problem of all hereditary monarchies: succession. Brothers, cousins, uncles, and nephews were constantly looking for opportunities to seize the throne by stabbing a royal relative in the back—sometimes with the connivance of neighbouring powers, or aggrieved elements from among the many peoples whom the Assyrians had colonised.

In this regard, one of the most extraordinary writings discussed by Collins is the Succession Treaty of Esarhaddon—a loyalty oath written up by the Assyrian king of the same name (r. 681–669 BC). Under its terms, vassals were required to swear to Aššur, the Assyrian national god, that they would recognise crown prince Aššurbanipal as royal heir and successor upon the king’s death. Lest such oath be broken, the tablet lists no fewer than 68 curses that would befall the oathbreaker, ranging from the medically precise (leprosy, blindness, death by vultures), to the sexually lurid (“May Ishtar make your wives lie in the lap of your enemy before your eyes”) to the underwhelmingly vague (“May Aššur decree an evil and unpleasant fate for you”).

If this ominous style sounds familiar, it may be because such Assyrian writings likely influenced the Jewish authors of Deuteronomy (“You will be pledged to be married to a woman, but another will take her and rape her. You will build a house, but you will not live in it. You will plant a vineyard, but you will not even begin to enjoy its fruit,” and so forth). Indeed, the Assyrians make cameos in several parts of the Bible, in which they are generally portrayed as a cruel and proud race that tormented the Jews. (In Isaiah 37:36, God becomes so enraged by Assyrian barbarism that “the angel of the Lord went out and put to death a hundred and eighty-five thousand in the Assyrian camp.”)

The Succession Treaty of Esarhaddon achieved its purpose: Three years after it was drafted, Esarhaddon died, and his son Aššurbanipal ascended to the throne—just as planned. He reigned for 38 years, from 669 BC till his death in 631 BC, a period corresponding to the height of Assyrian territorial expansion.

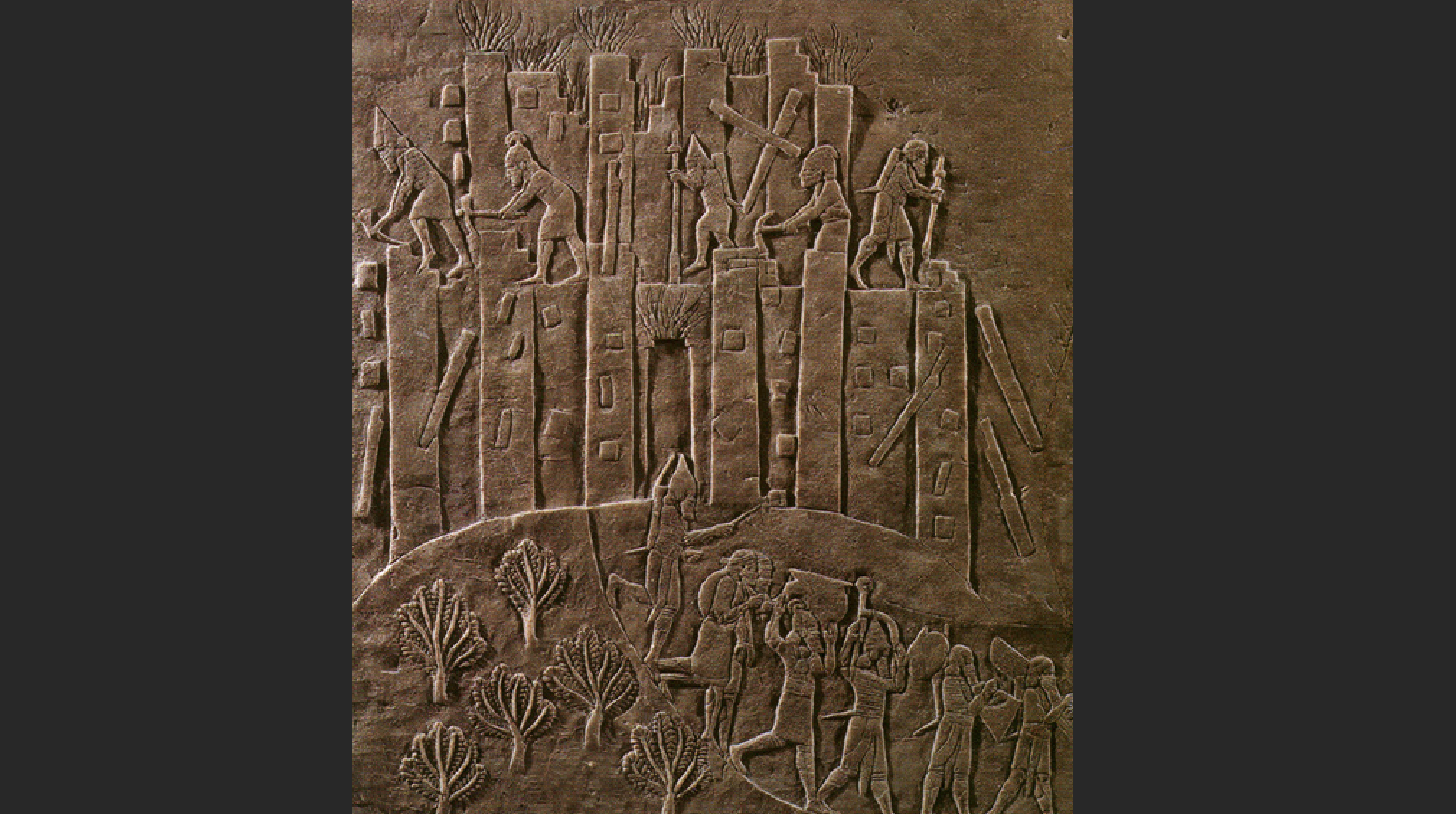

Unfortunately, Aššurbanipal was something of a sadist, inflicting what we would now call genocide upon the conquest of various enemy-held cities. He boasted, for instance, of completely destroying the capital of neighbouring Elam (in modern-day Iran), plundering its temples, sowing farmland with salt, and enslaving those he hadn’t annihilated.

“For a distance of a month and twenty-five days’ journey, I devastated the provinces of Elam,” he claimed. “The dust of Susa, Madaktu, Haltemash, and the rest of the cities I gathered together and took to Assyria... The noise of people, the tread of cattle and sheep, the glad shouts of rejoicing, I banished from its fields.” Such campaigns filled Aššurbanipal’s royal coffers with plunder, but also helped unite Assyria’s enemies against this marauding king.

During the latter part of his reign, Aššurbanipal seems to have become depressed and possibly even mentally ill. One of his final inscriptions laments that “I cannot do away with the strife in my country and the dissensions in my family; disturbing scandals oppress me always. Illness of mind and flesh bow me down; with cries of woe I bring my days to an end. On the day of the city god, the day of the festival, I am wretched.”

The Assyrian Empire went into decline, and its many enemies seized the opportunity to attack. Soon, an alliance of Median and Babylonian troops would destroy both the Assyrian religious capital of Assur, and the administrative capital of Nineveh—repaying all the gratuitous destruction and cruelties that Aššurbanipal had inflicted in the process.

In the space of a generation, a 1,400-year-old empire went from its geographical maximum to non-existence, a stunning pace of collapse that makes the fall of the Roman Empire look positively glacial by comparison.

Marco Polo (1254–1324) is likely the most famous merchant who ever lived. Even small children know his name, thanks to the swimming-pool game that shares his name (though no one is quite sure why). Less famous is Rustichello da Pisa, the florid romance writer who served as ghostwriter for Polo’s legendary work, The Travels of Marco Polo.

The two men struck up their partnership in a Genoese prison, after both had wound up on the wrong side of that city-state’s commercial rivalry with Pisa and Polo’s native Florence. The fact that the book became one of the great blockbusters of the European Middle Ages is owed to the combination of Polo’s extraordinarily detailed knowledge of the Orient’s great trading civilisations with Rustichello’s sensational writing style. The former appealed to the professional merchant class; the latter to the great reading public (such as it was before the invention of the printing press).

Sharon Kinoshita, a specialist in medieval French literature at the University of California, Santa Cruz, knows Polo as well as any modern scholar, having published her own translation of his Travels in 2016. (Kinoshita’s language specialty is apt, as The Travels was not written in Italian, but rather in an adapted form of French known as lingua franco-veneta, then commonly employed by Italian writers who, in this age before Dante, regarded their mother tongue as too vulgar for literary use.) In a beautifully illustrated new book, Marco Polo and His World, she revisits The Travels, but this time as guide instead of translator. Her goal is to provide readers of The Travels with the historical information they need to situate Polo’s adventures in their correct thirteenth-century context.

Polo was still in his teens when he made his first trip to the court of Qubilai (Kublai) Khan at Shangdu (often anglicised as “Xanadu”). Yet Kublai was so impressed by Polo’s communications skills that he hired the youngster as a foreign emissary, dispatching him to other Asian ports of call. (According to Rustichello’s prologue, Polo somehow had managed to learn Mongolian—along with several other unspecified languages—even before meeting the khan.)

Polo describes “Cathay” (northern China, as distinct from the Southern Song Empire, which Kublai required more time to subdue) as a land of wonders, many of them never before observed by Europeans. He was especially awed by the port of Quinsai (modern Hangzhou); and by Khanbaliq, Qubilai’s winter capital in modern Beijing, where “greater quantities of the most costly and most worthy things come to this city than to any [other]. For know in truth that each day, more than 1,000 carts loaded with silk enter this city.”

As Kinoshita emphasises, Kublai’s world was, in some ways, new to the local Chinese population as well, as their lands had only recently been folded into the Mongols’ enormous continent-spanning empire. As a means to legitimise his conquests, Kublai styled himself as the founder of a legitimate dynasty in the ancient Han tradition—known to history as Great Yuan. But there was no disguising the fact that China had effectively been taken over by Mongolian steppe warriors.

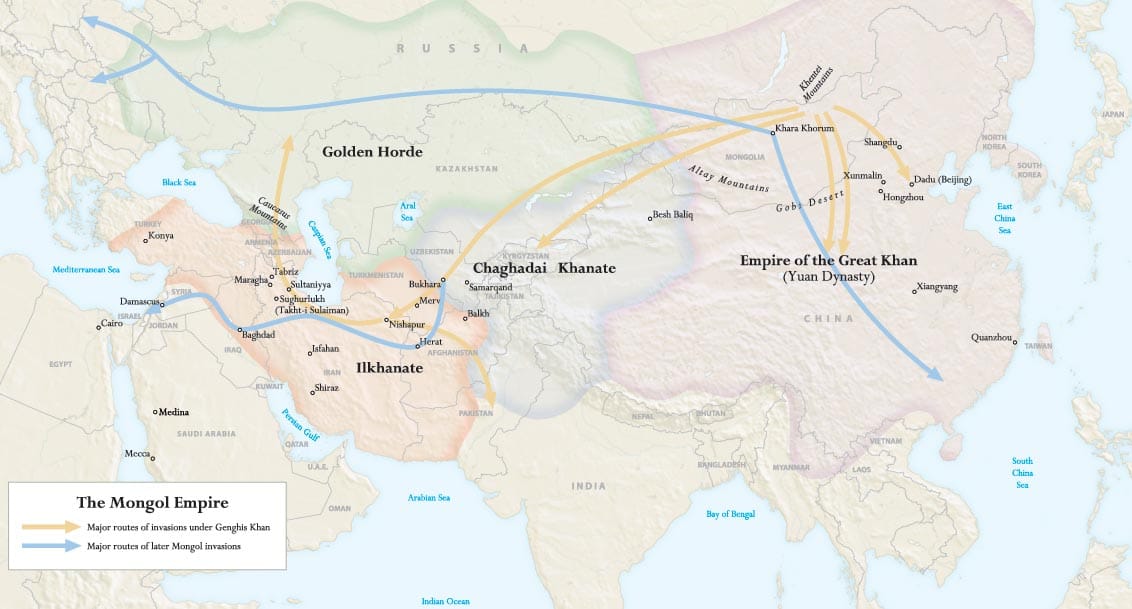

The fortunes of Mongol subjects varied according to region, as the empire became politically subdivided among Genghis Khan’s descendants (including Qubilai, a grandson of the founding khan) following a 1259 succession crisis. In eastern Europe, the Mongols were feared as ruthless pillagers and despots. And the English Benedictine monk Matthew Paris described them as a “monstrous and inhuman race” of cannibals. But as Marie Favereau emphasises in her 2021 book, The Horde: How the Mongols Changed the World (which focuses on a separate khanate, the Golden Horde), the sheer scope of Mongol conquests also facilitated new opportunities for international trade and cultural exchange.

During this Pax Mongolica, the Mongols popularised the use of paper money; and created the yam, a long-distance postal relay service with 1,400 stations that allowed messages to be transmitted across Eurasia in a matter of just a few months. (“I tell you that such men as these often bring the lord [Qubilai] fruit from ten days away in one day,” Polo informed readers.) To facilitate communication, Qubilai even ordered the creation of a new universal script, known as ’Phags-pa, into which scribes could transliterate all of the many languages spoken in his empire. And it was this globalised world that Polo entered when he sailed out of Venice at age seventeen.

Polo was very much a capitalist avant la lettre, which may be one reason The Travels proved so popular. The standard literary genres of the era were dominated by hagiographies of monarchs, along with religious texts documenting the lives of saints. But wherever he went, Polo was primarily interested in the merchant class and those it employed—what they bought, what they sold, and how they conducted business. “Even the well-born nobles who would hold pride of place in other civic descriptions are nearly squeezed out by the attention given to merchants, craftsmen, and sailors,” Kinoshita writes of The Travels.

As for Polo’s broader observations of eastern peoples and their cultures, it is something of a mixed bag, ranging from surprisingly enlightened to hilariously ignorant.

Being a staunch proto-capitalist, Polo seemed impressed by the sheer diversity of merchants mixing freely in China’s great commercial hubs—including Jews, Muslims, and members of the various Christian sects—a laissez-faire atmosphere that would have been unthinkable in thirteenth-century Europe. But when it came to areas of Asia (India, in particular) that were seen as more primitive, he and Rustichello trafficked in all sorts of nonsense—material that did not reflect Polo’s first-hand observations, but rather simply recycled overheard folklore. Many parts of The Travels are characterised by a mash-up style, whereby Polo casually intermingles banal reports about natural resources and local flora with horrific fictions—as in his description of the Andaman Islands in the northeastern Indian Ocean:

Now know in all truth that all the men of this island have heads like dogs and teeth and eyes like dogs… They are a very cruel people; they eat as many men as they can catch, if they are not their people. They have all kinds of spices in abundance; their food is rice, milk, and meat of all kinds; they also have fruit which is different from ours.

Such descriptions will obviously strike the modern reader as, let us say, problematic. But Kinoshita’s take on these flourishes is laudably nuanced. She notes that however absurd Polo’s descriptions may have been, they weren’t any more far-fetched or denigrating than those written up by Arab, Persian, and Chinese writers of the same period. Put another way: Polo’s attitudes can’t be neatly shoehorned into the stigmatised category of thought now known as “Orientalism.”

As the author notes, moreover, The Travels was published, in large part, to satisfy the enormous appetite for “wonders” (mirabilia and merveilles, in Latin and French respectively) among both Christian and Islamic readers during the Middle Ages. The original French title of Polo’s book was Livre des merveilles du monde; and it was one of just many famous books from the period that purported to catalogue the mysterious and other-worldly phenomena that existed on the other side of the planet.

To give Polo his due, many of the “marvels” he reported served to cast local populations in a positive light. In regard to the Indian province of Lar, for instance, he reported on the abstemious lives of the “Yogi,” holy men whom he praised as “the best merchants in the world and the most truthful.”

What’s more, he added, “they fast all year and drink nothing other than water.”

It’s a claim that’s plainly at odds with the laws governing human biology—and so, like much else in The Travels, must be read as fiction. But surely, it speaks well of Polo’s intentions that he extended his credulity to fables that cast these exotic cultures in such flattering terms. At the very least, I hope, it means we can go on listening to blindfolded children grope around swimming pools shouting out Marco Polo’s name without chastising them for being insensitive.