With respect to sexuality, there is a female human nature and a male human nature, and these natures are extraordinarily different, though the differences are to some extent masked by the compromises heterosexual relations entail and by moral injunctions. Men and women differ in their sexual natures because throughout the immensely long hunting and gathering phase of human evolutionary history the sexual desires and dispositions that were adaptive for either sex were for the other tickets to reproductive oblivion.

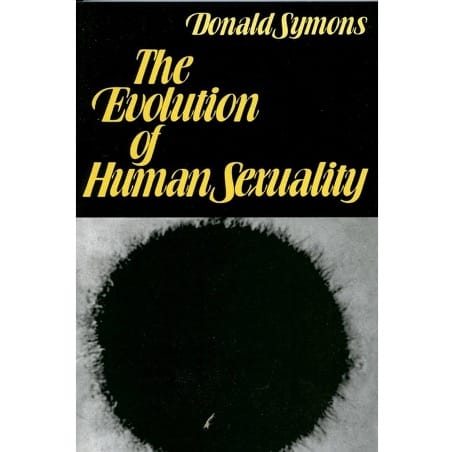

This bold yet qualified proclamation was how Donald Symons announced the theme of his epochal 1979 book The Evolution of Human Sexuality (EHS). Symons, who died of cancer last year at 82, is remembered with awe and affection by the legions of evolutionary psychologists and sexuality researchers he influenced. His extraordinary little book opened up vast new intellectual spaces, not just for an understanding of sexuality itself but for an understanding of the relevance of evolution to the human condition and of the nature of conscious experience.

Symons did not, of course, originate the idea that men and women have different sexual natures. According to the doggerel falsely attributed to William James, Dorothy Parker, and others, “Hoggamus higgamus, men are polygamous; Higgamus hoggamus, women monogamous.” Symons explained the grain of truth in the rhyme (and the grains of falsehood) in the teeth of intellectual complacency and sometimes fierce opposition from many sectors of the 1970s zeitgeist. It was the heyday of the doctrine that the human mind was a blank slate and that human nature was a dangerous idea. Second-wave feminism, recoiling from pseudoscientific stereotypes of women’s abilities, found it expedient to assert that the sexes were innately indistinguishable, with all differences coming from the “roles” that society assigned people, roles that could be rewritten in the name of equality.

The biology-friendly alternatives of the day were problematic for different reasons. The new approach called sociobiology often applied evolution to human behaviour in a patently implausible way, assuming that natural selection programmed us to maximise the number of babies we bring into the world. It sometimes made sweeping claims about the sexes that were barely more sophisticated than higgamus-hoggamus. Sex researchers, for their part, fell back on the folk theory that evolution works toward the greater good, and spun their research to valorise wholesome relationships and provide moralistic uplift. Many claimed that sex differences were complementary, and that human sexual desire was an adaptation for monogamous pair-bonding.

Symons’s education, filtered through a keen analytical mind and an unsentimental eye for human foibles, made him resistant to these facile notions. (“Talk of why… humans pair-bond like gibbons,” he wrote, “strikes me as belonging to the same realm of discourse as talk of why the sea is boiling hot and whether pigs have wings.”) As an undergraduate psychology major at UC Berkeley in the early 1960s, he was excited by the idea in Robert Ardrey’s 1961 bestseller African Genesis that humans evolved a nature adapted to a vanished world (while sceptical of some of the book’s fanciful specifics). Symons’s interest, at that time and throughout his career, was in the human psyche, but he was advised that academic psychology at the time had no room for evolutionary thinking and that he could pursue his interests only through biological anthropology.

Continuing at Berkeley, he did his thesis (later turned into a book) on rough-and-tumble play in rhesus macaques, which he argued was practice for fighting. Symons’s anthropological training equipped him with an understanding of primate behaviour, though he resisted extrapolating from any primate species to humans. (Using gibbons as a model to understand humans, he said, made as much sense as using humans as a model to understand gibbons.) It also prepared him to test theories of human sexuality against the ethnographic record rather than just convenience samples of university students or literate survey responders. This was decades before social scientists were sensitised to the pitfalls of generalising from WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich, Democratic) societies.

During Symons’s graduate years, a young Richard Dawkins taught at Berkeley, and Symons learned from him the rigorous new understanding of evolution originating from George Williams and William Hamilton in which selection consists of competition among replicators (“selfish genes”). Symons also absorbed Robert Trivers’s insight that all social relationships—families, couples, cooperation partners—are both bound by overlapping genetic interests and riven by divergent ones.

Symons’s analysis of human sexuality began with the fundamental distinction between the sexes (newly relevant in our era of confusion about the biological basis of sex): females are the sex that produces large, immobile gametes (eggs); males are the sex that produces many mobile ones (sperm). This contrast opens up selection pressures for the evolution of other sex differences, which multiply the asymmetry in many species, especially mammals, by selecting for greater investment in offspring by females than males. Trivers worked out the behavioural implications. The greater-investing sex, usually female, is the rate-limiting step in reproduction, so a male’s reproductive success depends on how many females he mates with, whereas a female’s reproductive success does not depend on how many males she mates with but on their genetic quality and ability and willingness to invest in their offspring. This in turn explains two phenomena of sexual selection which had fascinated Darwin in The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex: in many species, males compete and females choose.

This brings us to the grain of truth in higgamus-hoggamus. Polygyny is massively more common in traditional societies than polyandry, and even in nominally monogamous ones, female sexuality is treated by both sexes as a scarce resource: Symons noted:

Among all peoples it is primarily men who court, woo, proposition, seduce, employ love charms and love magic, give gifts in exchange for sex, and use the services of prostitutes. And only men rape. Everywhere sex is understood to be something females have that males want; it constitutes a service or favor that females in general can bestow on or withhold from males in general, although “favorless” intercourse also occurs, and the exchange may be reversed in certain circumstances.

(The bold generalisation “among all peoples” tells a story. Symons enjoyed a lifelong dialogue with his friend, UC Santa Barbara colleague, and sometimes landlord, the cultural anthropologist Donald Brown. Brown lost a bet with Symons that he could find exceptions in the ethnographic record to each of Symons’s claims about universals in human sexuality. Chastened, Brown rethought the anthropological dogma that cultures could vary without limit and went on to write the classic 1991 book Human Universals.)

But human sexuality defies the rhyme in important ways. Homo sapiens, Symons pointed out, is atypical among mammals in the degree to which fathers invest time, care, and resources into their children and the children’s mothers. But a man’s investment is optional—he can sire a child with a few minutes of copulation—whereas a woman’s is obligatory, committing her to nine months of pregnancy and, in traditional societies, years of lactation. This flexibility explains why human sex differences are found in tacit negotiations between men and women rather than in overt polygamy, as with harem-holding gorillas. It also opens up the temptations of illicit sex. A man can multiply the number of his descendants by sleeping with additional women, and a woman can enhance the fitness of hers by sleeping with the right man. The opportunities may be rare, but the reproductive consequences substantial, and the mind should be sensitive to the possibilities even if individual people rarely find themselves in a position to act on them.

Symons noted another reason that we should not expect the evolutionary economics of reproduction to determine behaviour. Natural selection is not a ghost in the machine that can pull the levers of behaviour in real time. It can only select genes that grow brains that have desires that, over the long run in the kinds of environments in which we evolved, resulted in more surviving offspring. We no longer live in those environments: the longstanding link between sex and offspring has been scrambled by contraception, adoption, artificial insemination, cow’s milk, the rule of law, the welfare state, equal opportunity, and other innovations of modernity. Natural selection has a speed limit in generations and could not possibly have remixed our genes to keep up. As a result we are turned on not by opportunities to make babies but by opportunities superficially resembling those that would have allowed our ancestors to make babies. It is not an embarrassment for evolutionary theory, then, but a necessary consequence that, for example, contraception is not a turnoff, and sperm banks are not plagued by reverse embezzlement.

For all these reasons, Symons insisted, the effects of evolution are manifested in psyche, not behaviour. Contrary to the behaviourism that is widespread among scientists, it is thoughts and feelings, not actions, that implement the metaphorical agenda of our genes. When we choose an action, we must compromise our wishes to accommodate those of other people and the constraints of the world. Our desires, by contrast, have the run of our imaginations. Consciousness, Symons noted, is designed to scope out unpredictable events and opportunities: “A human being is a feeler, an assessor, a planner, and a calculator… The proximate goal of mental activities always is the attainment of emotional states, and… mind is adapted to cope with the rare, the complex, and the future: what is ordinary, predictable, or simple ceases to take up valuable space in awareness.” So as we play the routine games of life, our imaginations seethe with wicked fantasies about sex, revenge, and leaps of status. The late Jimmy Carter was one of our more monogamous presidents, but as he confessed in his notorious 1976 Playboy interview, he had often committed adultery in his heart.

Symons’s insistence that natural selection left its fingerprints in consciousness rather than behaviour led to the idea that a new Darwinian science of humans should be an evolutionary psychology, with a focus on thought and feeling, distinct from the behaviourist approaches of sociobiology, behavioural ecology, and Darwinian anthropology. At UCSB he joined forces with Brown and with a third colleague, Napoleon Chagnon, to hire the brilliant young anthropologist John Tooby, who had had an epiphany that there could be a science of mental life, after taking a course on psycholinguistics as a Harvard undergraduate. Around that time UCSB also hired the cognitive psychologist Leda Cosmides (who was married to Tooby), and the trio, together with a small circle of visitors, plotted to make evolutionary psychology an academic reality at UCSB and beyond. (Symons, Brown, and Tooby died within a year of each other; Chagnon five years before.)

Symons’s psychological mindset allowed him to take on other obvious features of human sexuality that had been ignored by the prissy sex science of his day:

That individual reproductive “interests” must in some degree conflict with one another may account for the intensity of human sexual emotions, the pervasive interest in other people’s sex lives, the frequency with which sex is a subject of gossip, the universal seeking of privacy for sexual intercourse, the secrecy and deception that surround sexual activities and make the scientific study of sex so difficult, the universal existence of sexual laws or rules, and the fact that in our own society “morals” has come to refer almost exclusively to sexual matters.

It also led him to take the advice of an anonymous reviewer of an early draft of EHS that he fortify his claims with observations from novelists and memoirists who had noticed the same foibles in human sexuality. And so EHS is salted with mordant aperçus from Michel de Montaigne, Marcel Proust, Mark Twain, Gustave Flaubert, Dorothy Parker, Saul Bellow, and other sages.

Symons explicitly confronted the standard alternative to his theory in which human sexuality consists in learning roles arbitrarily assigned by the surrounding culture. He argued that this consensus had been given a free pass in intellectual life and did not stand up to empirical reality:

In fact, human males appear to be so constituted that they resist learning not to desire variety despite impediments such as Christianity and the doctrine of sin; Judaism and the doctrine of mensch; social science and the doctrines of repressed homosexuality and psychosexual immaturity; evolutionary theories of monogamous pair-bonding; cultural and legal traditions that support and glorify monogamy; the fact that the desire for variety is virtually impossible to satisfy; the time and energy, and the innumerable kinds of risk—physical and emotional—that variety-seeking entails; and the obvious potential rewards of learning to be sexually satisfied with one woman.

He also parried the criticism that evolutionary explanations are after-the-fact just-so stories by drawing out surprising tests of his theory that men and women evolved with different sexual natures usually masked by mutual compromise. In homosexuality, the object of sexual desire is switched but the nature of each sex’s desire is preserved, and those desires can be indulged without the usual compromise with the desires of the opposite sex. Homosexual relations, then, offer a clearer window into what each sex wants, and the differences revealed are dramatic. Gay men, far more than lesbians, seek casual sex with many partners, chosen for their youth and beauty—not because the men are gay but because they are men.

Erotic beauty itself is a paradox, Symons argued, which can be resolved only by recognising that “beauty is in the adaptations of the beholder.” Many other things are attractive because they signal qualities of the object that make interacting with it pleasurable, and the attractiveness can be learned by association. Plump red berries taste sweeter; fuzzy cashmere feels softer and warmer. But while beauty kindles sexual desire, there’s no reason to expect that an attractive person is a more skilled lover or a better fit with one’s body. The qualities signalled by beauty, Symons noted, fall outside the realm of immediate experience; they signal the probability of conceiving a viable child. The physical lineaments of beauty are signals of fertility and fitness (or at least were, prior to cosmetics): signs of health, youth (especially in women), symmetry, sex-appropriate hormones, and similarity to a morphed composite of the local population (a cue to the adaptive target of ongoing selection).

The Evolution of Human Sexuality is filled with insight on other manifestations of sexuality, including nudity, jealousy, fashion, harassment, pornography, arousal, dating, prostitution, marriage, objectification, the female orgasm, adolescent ardour, and the mating marketplace. I’m not the only psychologist who often returns to the book more than four decades after it was published and is repeatedly astounded by its depth, subtlety, and timeliness.

After the book was published Symons kept a low academic profile, with a smattering of theoretical chapters and one article he was particularly proud of, “The Stuff that Dreams Aren’t Made Of.” Symons noted that dream content is rarely tactile, auditory, or olfactory, though it is rich in sight and motion. He proposed that dream experience is restricted to the sensory channels that are irrelevant during the darkness and immobility of sleep, but is sequestered from the channels that must be kept open for vigilance against danger. That’s why we rouse ourselves out of sleep with auditory alarms, and why the quintessential test of whether we’re dreaming is to say, “pinch me.” He also coauthored a short book on erotic fan fiction and female sexuality with Catherine Salmon, Warrior Lovers.

Symons himself was no warrior. Though intellectually fearless, he was personally gentle and restrained. He had no stomach for the intellectual warring and sheer nastiness that greeted evolutionary psychology in its early days, a preview of today’s cancel culture. When he turned sixty he retired from UCSB and most academic life to enjoy the pleasures of Santa Barbara with his wife Paulina Ospina, a public health scientist and director of a humanitarian nonprofit. He rarely travelled, saying that no experience could be so much better than Santa Barbara that it made up for the ordeal of plane travel. But he did exercise his wit by regularly entering the New Yorker Cartoon Caption Contest, making the finals six times and winning once.

He also shared his wit and wisdom in conversation and in comments on his friends’ writing. In an early draft of The Better Angels of Our Nature, I offhandedly referred to the Yanomamö of Amazonia as “the fierce people,” alluding to the title of Chagnon’s famous ethnography. Symons called out the inadvertent essentialising: “Are the old women fierce? Are the babies fierce? Do they eat fiercely?”

And in a draft of The Blank Slate I suggested that the emotion of romantic love was an adaptation to the overlap of interests in a couple, their genetic fates united in their children. The extreme case of this overlap would be a hypothetical couple on a desert island who were perfectly monogamous, resistant to pressure from kinfolk, and destined to die at the same time. Symons disagreed. Consciousness, he reminded me, is an adaptation to uncertainty. We savour food because food was hard to get during our evolutionary history. We don’t normally feel delight in oxygen, even though it is crucial for survival, because it was never hard to obtain; we just breathe. Our strong emotions were selected to cope with the ineluctable risk of loss that is part of the human tragedy. In the idealised thought experiment of a perfectly faithful lifelong couple,

There would be no falling in love, because there would be no alternative mates to choose among, and falling in love would be a huge waste. You would literally love your mate as yourself, but that’s the point: you don't love yourself, except metaphorically; you are yourself. The two of you would be, as far as evolution is concerned, one flesh, and your relationship would be governed by mindless physiology, like the formation of gametes or release of hormones. You might feel pain if you observed your mate cut herself, but all the feelings we have about our mates that make a relationship so wonderful when it is working well (and so painful when it is not) would never evolve. Even if a species had them when they took up this way of life, they would be selected out as surely as the eyes of a cave-dwelling fish are selected out, because they would be all cost and no benefit. In short, without the possibility of suffering, what we would have is not harmonious bliss, but rather, no consciousness at all.