Australia

Fighting Fire with Fire

We know how to prevent catastrophic bushfires. For more than half a century, Western Australia has been reducing forest fuel loads through a systematic program of ‘prescribed burns.’

Since 7 January, a series of massive wildfires have spread across portions of Los Angeles and surrounding areas, destroying more than 10,000 homes and taking at least 25 lives. The disaster has focused global attention on a phenomenon that endangers many other parts of the planet—including my own country, Australia, where we’ve learned hard lessons about what works to prevent such tragedies, and what doesn’t.

In this regard, it’s instructive to revisit the 1961 Western Australian bushfires, which razed about 150,000 hectares—or 150 square kilometres. Four entire towns were wiped off the map, never to be rebuilt. The country’s southwestern tip, where these fires occurred, has a Californian-style climate. The state’s largest city (and capital), Perth, is sandwiched between the Indian Ocean and the Darling Scarp. Suburbs are nestled within this escarpment, whose forested ecosystem is known as Jarrah Forest. A prominent feature is the tall, highly flammable eucalyptus tree, which has evolved to flourish in environments that frequently experience fire.

The 1961 fire season was so severe that it caused Western Australians to rethink their reliance on a forest-management approach that had focused on the complete prevention and suppression of fires. Summer storms inevitably bring lightning, which inevitably causes fires. And historical data gleaned from samples of long-lived plant species indicate that fires have occurred every three to four years in Western Australia’s Jarrah forests. It became clear that preventing this pattern from recurring entirely is impossible. Another approach was needed.

This reality had formerly been obscured by the fact that communities living adjacent to or within highly flammable forests had been benefiting from the accumulated legacy effects of thousands of years of Indigenous woodlands management. This featured the use of localised low-intensity fires that cleared out the underbrush—an advantage for Indigenous hunters seeking to replenish their hunting grounds and facilitate their own seasonal migrations.

Early European settlers and herders learned from these traditional techniques. But amid the population boom of the 1900s, this approach changed. Fire became viewed as an enemy in and of itself, and so the focus turned to the suppression of any fire. Indigenous peoples were legally prevented from conducting culturally rooted land-management practices, as were the graziers (ranchers) who’d copied their techniques. As a result, the growth of underbrush went unchecked, thereby creating a massive build-up of kindling materials on forest floors.

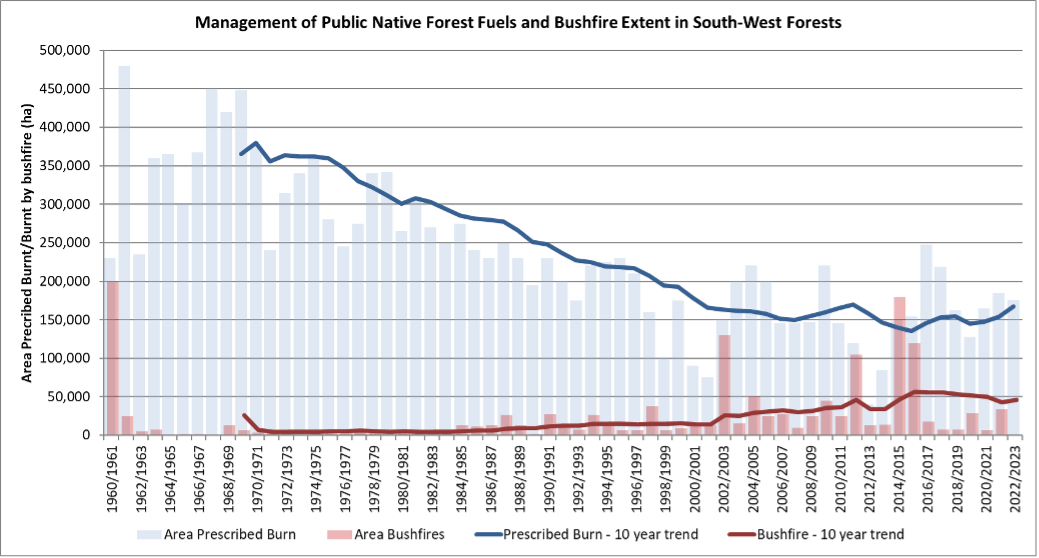

And so 1961 effectively became Year Zero for a new fire-management regime in Western Australia, whose development was led by enterprising foresters and land managers. Their methods included the use of controlled burns of woodlands. Using aerial incendiary methods, managers were able to treat more than 300,000 hectares every year—or about one seventh of the total forest area (meaning that treatment of all areas required a seven-year cycle). Targets were set, and regional managers were empowered to take the steps necessary to protect towns and economies within their assigned districts. With the assistance of a thriving timber industry, authorities were able to construct and maintain a network of logging roads that did double duty as firebreaks—forming the edges of prescribed burns. Such techniques have been maintained to this day.

The system isn’t perfect. As with all such endeavours, a sense of complacency inevitably arose, and the rate of forest management dipped far below its high-water mark in the 1970s. After a particularly bad series of fires during the early 2000s, additional funding was provided by the Western Australian government. As a result, the annual area treated is approaching 8 percent of total forest area—or 200,000 hectares—up from a low of about 5 percent.

As with many land-management activities, there is a lag between treatment and effect: Stop doing the work, and one may coast for a while on the basis of past labours, until reality bites. Then there’s a painful period of rebuilding capital, albeit for little short-term return. And so it is only now that Western Australian residents are beginning to see the benefits from investments made over the last decade.

A lesson here is that policymakers must play the long game. We’ve also learned that a wide range of stakeholders must be involved, from local and state government, to industry, to individual residents.

In the state of Western Australia, primary responsibility for the prescribed burning program lies with the Parks and Wildlife Service of the Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions. As they work with fire throughout the year, the region’s Parks and Wildlife firefighters now rank among the best in the world. They can read the landscape, and envisage how a fire, once ignited, will move through it. Along with colleagues from other agencies and regions, they are frequently deployed to assist in crisis situations internationally, including in the United States and Canada.

Prescribed burns do not eliminate the risk of bushfires. Natural leaf fall replenishes surface fuels. So unless an area of forest is freshly burned—within the time span of several months—a fire will still be able to travel through it. But the intensity of that fire, which is to say its energy output and damage potential, will be much lower thanks to the reduced fuel load. Less intense fires are slower, and easier to both suppress and contain.

Prescribed burns are just one mitigation tool. Others include forest thinning and other forms of “mechanical fuel reduction,” whereby small trees, branches, and underbrush are physically cleared as a means to reduce the quantity and continuity of combustible vegetation. (This is what US President Donald Trump is referring to when he speaks of other countries “raking” their forests.) But to be effective, such fuel-reduction efforts must be combined with a corps of trained firefighters, supported by water bombers, which can be activated in a timely fashion by spotters in fire towers, aircraft, and (now) AI-powered cameras.

The idea here is that while correct forest-management policies will help ensure that fires burn less hot and travel less fast than they otherwise would, they can still do tremendous damage if they aren’t responded to quickly.

An example I observed personally—the first of two fires that started in Jarrah Forest in mid-summer 2023—helps illustrate these principles. It had been just two years since the area had been pre-emptively burned. Thanks to the low fuel loads, it required only two Parks and Wildlife fire trucks and one bulldozer to contain the fire to just sixty hectares, despite the presence of significant winds (which, as we’ve seen in California, can greatly accelerate a fire’s spread).

Contrast this with a second fire that started around the same time, just ten kilometres away. In that case, a lightning strike hit an area whose fuel load hadn’t been culled for sixteen years. Despite the best efforts of fire crews, that fire escaped from the native forest and burned into timber plantations, inflicting millions of dollars worth of damage on valuable tree crops, and destroying at least one home. The fire eventually impacted an area of over 6,000 hectares; and, at its peak, was being fought by forty fire trucks, almost a dozen pieces of earth-moving equipment, and multiple aircraft—all paid for by the taxpayers of Western Australia.

This tally does not include damage to farm infrastructure, lost earnings by volunteer firefighters, economic disruption caused by closed roads, and the psychological stress placed upon the community.

The choice we face is not between fire and no fire. Rather, it’s between mild prescribed fires that are set and managed at a time of our choosing, versus uncontrolled and extremely intense wildfires that ignite during the hottest and driest times of the year

It should be said that prescribed burning programs are not without their critics. There are concerns about the effects of smoke on human health and on local grape-harvesting enterprises, as well as other flora and fauna. Prescribed burns sometimes escape their intended target areas, and can threaten fragile ecosystems, such as peat swamps.

By my observation, however, much of the criticism comes from groups whose members aren’t personally impacted by bushfire risk. Moreover, they often present a false dichotomy: The choice we face is not between fire and no fire. Rather, it’s between mild prescribed fires that are set and managed at a time of our choosing, versus uncontrolled and extremely intense wildfires that ignite during the hottest and driest times of the year. To their credit, political leaders in Western Australia understand this, and so have steadfastly maintained their support for the mitigation program.

But what amount of prescribed burning is optimal? As in many areas of policymaking, Australia’s federated structure presents a natural laboratory.

The state of Victoria, on the country’s east coast, follows a very different program from that of West Australia—one largely dictated by urbanites who are (typically) insulated from the results of poor land management. In Victoria, activist opposition to sensible forest-management policies has led to the destruction of the region’s once-thriving native-forest timber industry (which also means that the state no longer has access to the roads maintained by timber sales revenue, nor to the skilled bulldozer operators who might be usefully deployed to help fight fires). Activists have used “lawfare” methods to stall, or even prevent, mitigation activities. And the state has cut firefighting budgets, which has resulted not only in diminished capacity, but a general state of demoralisation among fire managers and volunteer firefighters within local communities.

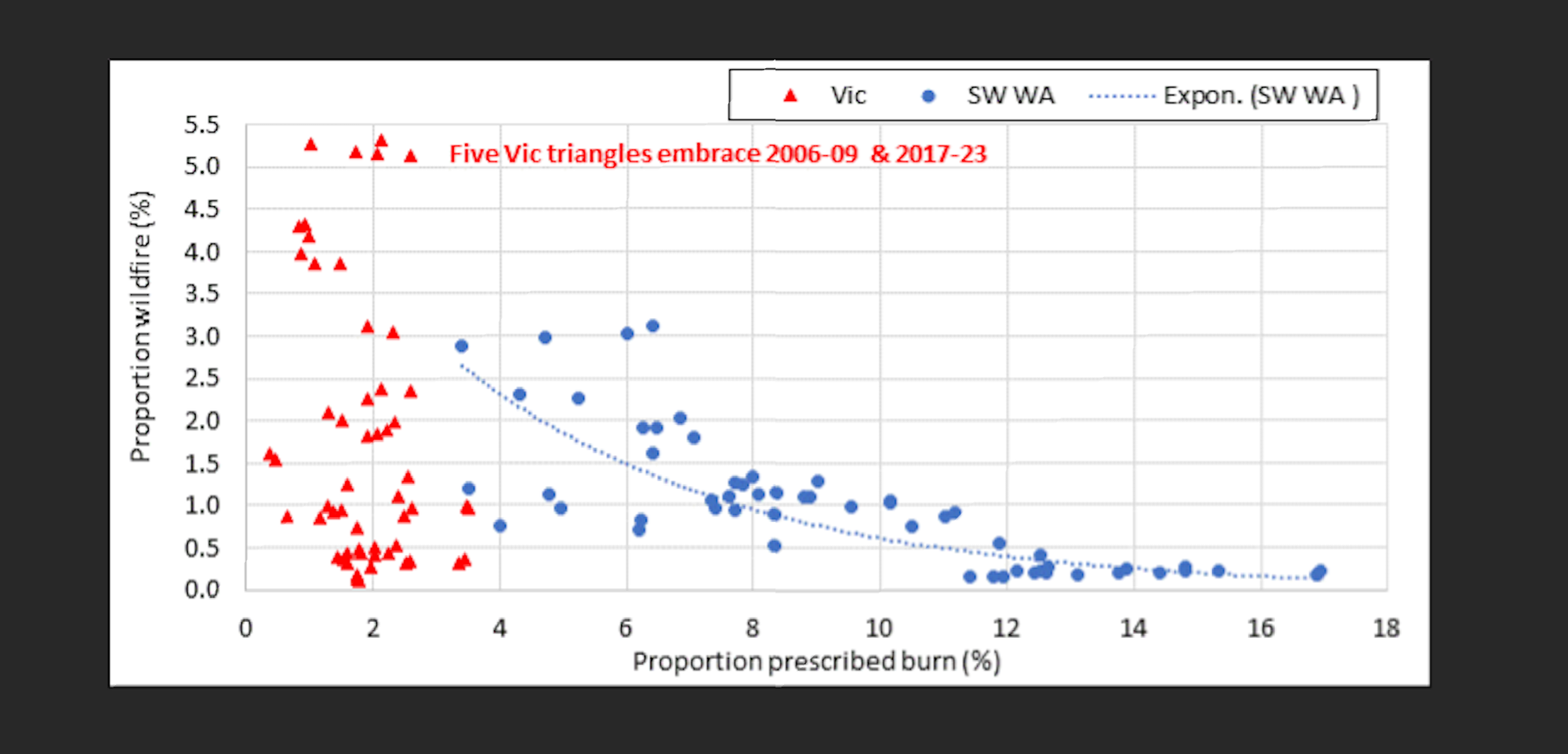

The figure that appears below—produced by John Cameron, a Victorian forester, based on the work of retired State Fire Manager Rick Sneeuwjagt—plots the proportion of land affected by wildfires in Victoria (represented by red triangles) and southwest West Australia (blue circles) as a function of the proportion of at-risk land subject to prescribed burns. (Y-axis values are averaged over annualised four-year cycles, while X-axis values are averaged over four-year cycles following prescribed burning operations.)

The path of the dotted blue line indicates that in Western Australia, as one might expect, higher rates of prescribed burns have been associated with a lower amount of land ravaged by wildfires. In Victoria, on the other hand, there is no obvious pattern—suggesting that the state’s (extremely modest) forest-management efforts do not even reach the baseline level required to generate a statistically observable abatement effect. (As readers may recall, in 2019–20, eastern Australia suffered a particularly devastating fire season. The corresponding data point may be found in the top left hand corner of the graph.)

Put another way, it seems that unless at least 4 percent of a region’s public forest area is treated in any given year, there will be no appreciable reduction in bushfire incidence. Such areas will thus be vulnerable to bushfires based on the vagaries of ignition, weather, and prevailing winds. The location, timing, and size of such fires will vary from year to year, but the predictable cycle of fuel accumulation followed by fire will remain constant.

Put another way, it seems that unless at least 4 percent of a region’s public forest area is treated in any given year, there will be no appreciable reduction in bushfire incidence

The takeaway here is clear, and likely applies in some fashion to California and other parts of the world that are at risk from wildfires—especially those areas with an increasingly dry Mediterranean-style climate, such as Portugal, Spain, and Greece: mega-fires will occur regularly unless governing authorities are willing to bear the economic and political cost of implementing large-scale forest-management regimes. Absent such investments, no amount of suppression capability—be it in the form of air tankers, bulldozers, or firefighters—will serve to contain the type of massive fuel-rich blazes that are now consuming parts of southern California.