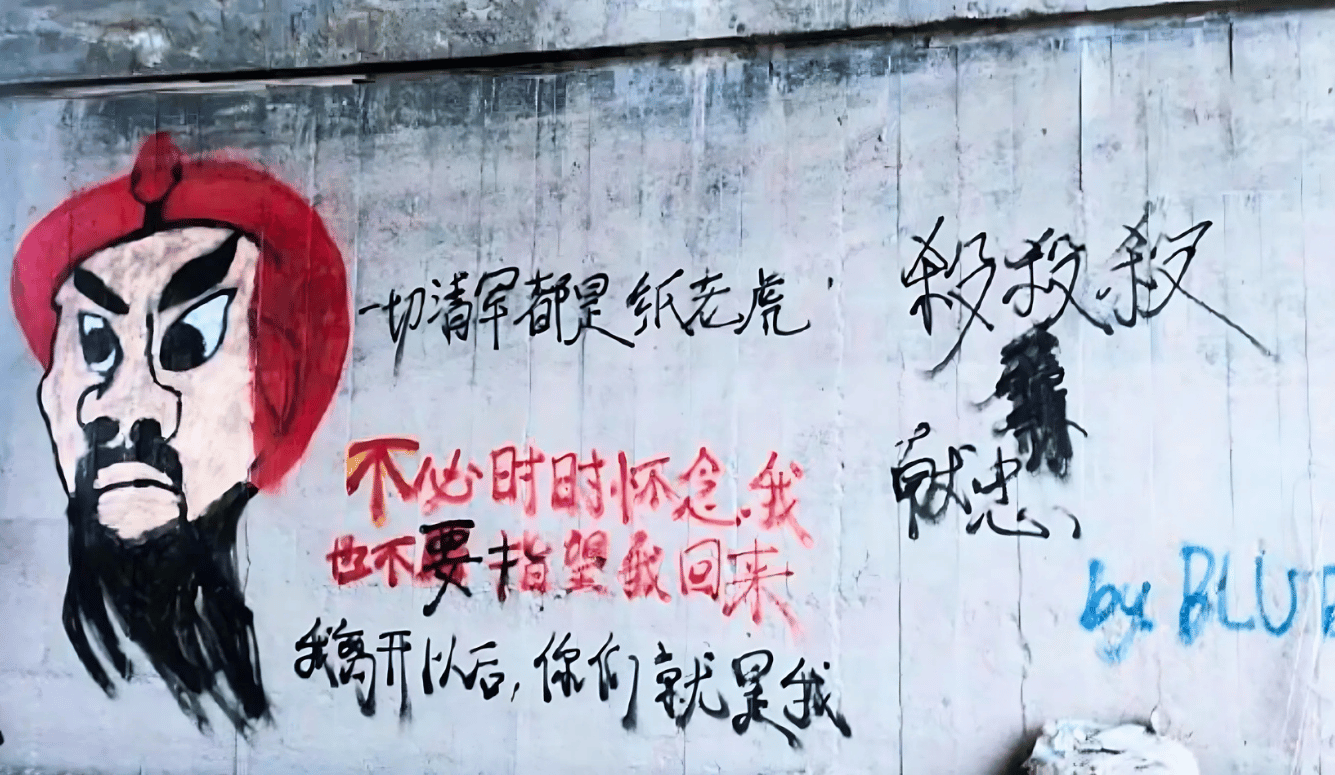

“Xianzhong!” shrieks the graffiti on city streets across China—a reference to Zhang Xianzhong, a Ming-dynasty peasant rebel. For the briefest of periods in the mid-17th century, Zhang ruled as rival emperor from a base in Sichuan province, and became famous for depopulating the region with a series of brutal and indiscriminate massacres. Today’s graffiti is sometimes accompanied by a blunt mandate, apocryphally attributed to Zhang: “Kill, kill, kill.” An acknowledgement of the tragedies currently blighting the nation, it also feels like an invocation of the spirit of Xianzhong; an instruction to his ideological heirs in modern China. They are certainly paying attention.

Far from the world of spray-painted alleyways and vandalised shopfronts, safely cloistered in the halls of their Beijing compound, China’s leaders are also responding. A Politburo meeting earlier this month sent “the most aggressive stimulus tone in a decade,” as Morgan Stanley economists put it. Gone is the “prudent” economic strategy pursued throughout President Xi’s long tenure; in its place we have the promise of “extraordinary” measures for 2025. (Specifics have not been provided.) With China mired in deflation—the longest streak this century—the Communist Party appears to have reached some kind of pain threshold.

It is the rest of society, of course, that really feels the pain. Ordinary people reached their breaking point some time ago, hence the spectre of Xianzhong. 2024 was the year of “revenge on society” attacks (bàofù shèhuì), in which individuals respond to the hopelessness of their situation by carrying out random mass murders. Beijing has always tried to direct public anger toward external targets, like Japan, but apparently that tactic will no longer suffice. Like an autoimmune disorder that causes the body to attack itself, China is now turning its rage inward.

Every few days, another tragedy is reported. Consider a single week last month. On 11 November, unhappy with the terms of his divorce settlement, a man ploughed his SUV into a crowd outside a sports complex in the port city of Zhuhai, killing 35 and injuring 43. Five days later, an underpaid factory worker ran amok with a knife at a college in the Yangtze River Delta, killing eight and injuring 17. Then, on 19 November, a driver careered into children outside a primary school in Changde, hospitalising many but failing, on this occasion, to kill anyone. This time, there was no waiting around for the police to arrive. Fired with adrenaline, parents of the injured children smashed the man’s car windows, dragged him into the street, and began beating him.

The CCP’s leaders have often seemed blind to realities on the ground in China. Think back to 2022, the sudden shock of the White Paper protests and the frantic ditching of the zero-COVID policy. But these new massacres have been a very public problem for several months now, and they appear to be increasing in frequency. It would take remarkable obtuseness to miss the significance of bàofù shèhuì.

In late November, the Supreme People’s Court convened a “special meeting” to address the phenomenon. The Court’s conclusions were couched in the usual communist jargon, telling us nothing: “All levels of people’s court should truly unify their thoughts and actions with the spirit of General Secretary Xi Jinping’s important instructions, always adhere to the guidance of Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era, thoroughly implement Xi Jinping Thought on the Rule of Law…” and so on and so forth. (China-watcher Simon Leys once compared reading this kind of thing to “swallowing sawdust by the bucketful.”)

The CCP also reverted to type by attempting to bury these stories. Foreign news teams in Zhuhai were forced to delete their footage of the November massacre, local media focused its attention on a military airshow taking place in the city, and the authorities binned floral tributes left at the scene. Meanwhile, a thousand miles to the north, multiple floral-themed displays graced China’s capital as if in mocking contrast. These projects had been commissioned for the 75th anniversary of the communist revolution. The Party will always prioritise itself over human life.

There have been calls for a crisis intervention system to identify “high-risk individuals” before they attack, but these individuals are themselves symptoms, and they will keep flaring up until the causes are identified. So what are they? The CCP has no real system for dealing with people’s grievances. Petitions to the government are largely ineffective. China also suffers from a disastrous sex imbalance, the legacy of Deng Xiaoping’s one-child policy and a sure accelerant for antisocial behaviour. Underlying mental-health problems were blamed for May’s Xiaogan massacre. And we might reasonably guess at politico-racial motivations for June’s knife attack on a group of American teachers in a Jilin park.

But economic insecurity is the common trigger. Take September’s Shanghai supermarket killer, who travelled to the city specifically to “vent his anger due to a personal economic dispute.” (He would murder three people and injure a further fifteen). China is riven by inequality, and its recent economic underperformance is only widening the gap. If Beijing has indeed grasped the scale of the danger, then we can guess that the “revenge against society” attacks were a major factor behind December’s policy reset.

While economic stress provides a working explanation of these outbursts, it doesn’t help us much. Suicide we might understand, but how can we explain the desire to take large numbers of random strangers with you? Worse, it’s not always completely random. The assailants often target schools (like October’s middle-aged knifeman in Beijing, who injured five, including three children), or hospitals (like May’s disgruntled ex-con in Yunnan, who killed two and injured 21). Perhaps murdering society’s most vulnerable is a way to hurt society as much as possible. The Communist Party, of course, has always treated the Chinese people as a single organism. For those who believe in this organism and have come to hate it, these attacks may serve as a method of striking directly at “China.” Individual victims, then, are only a means to an end.

There is also a growing sense of powerlessness. Chinese citizens have learned to live without political or cultural power in the 75 years since the revolution, but during China’s historic post-Marxist rise they at least enjoyed a degree of economic freedom. For those who kept their mouths shut and their heads down, paying off the right people at the right time, there was the potential to become masters of their own fate. That option has now disappeared for many Chinese. Now they have no power at all. So they choose to “lie flat” and “let it rot,” while Xi Jinping helpfully advises them to “eat bitterness.” This is not a winning combination. Driven to the point of madness, some will find the agency they crave in the ultimate taboo violation; the most extreme method of stamping their will on the external world.

No theory fully satisfies. In contrast to Islamist terror attacks—similarly murderous, similarly random—there is no ideology here to convince perpetrators of the rightness of their actions. There is simply an empty nihilism and a curious lack of empathy. Detailed studies are necessary but unlikely. The Communist Party has always proven itself uniquely clueless when it comes to understanding the psychology of the nation it governs.

Will the Politburo’s “aggressive stimulus tone” bring an end to the revenge-against-society phenomenon? That depends on how aggressive it turns out to be. “Implementation,” warn those Morgan Stanley economists, “remains uncertain.” The right time for change was really two years ago, following zero-COVID. Beijing waited too long to abandon its pandemic policy, thus creating the current mess, and it has since waited too long to mitigate the damage. Now the regime is faced with the additional danger posed by prolonged economic stagnation. If things continue in this vein, it will make it all the more difficult to banish the ghost of Xianzhong.