There is something mesmerising about the assassin, a brooding young man described as “exceptionally handsome, above the average in height, slim, well-built, with beautiful dark eyes and dark brown hair.” He is well-read and articulate, educated at the best universities. There is comparatively little sympathy for his victim, who is widely regarded as an antisocial leech who became, as one person put it, “rich as a Jew” by exploiting or “wearing out the lives of others.” Others referred to the deceased as a “louse” or “parasite,” who lived by taking advantage of those in need. The consensus seemed to be that, while the crime was doubtless unfortunate for the victim’s immediate friends and family, society as a whole was better off as a result of the murder.

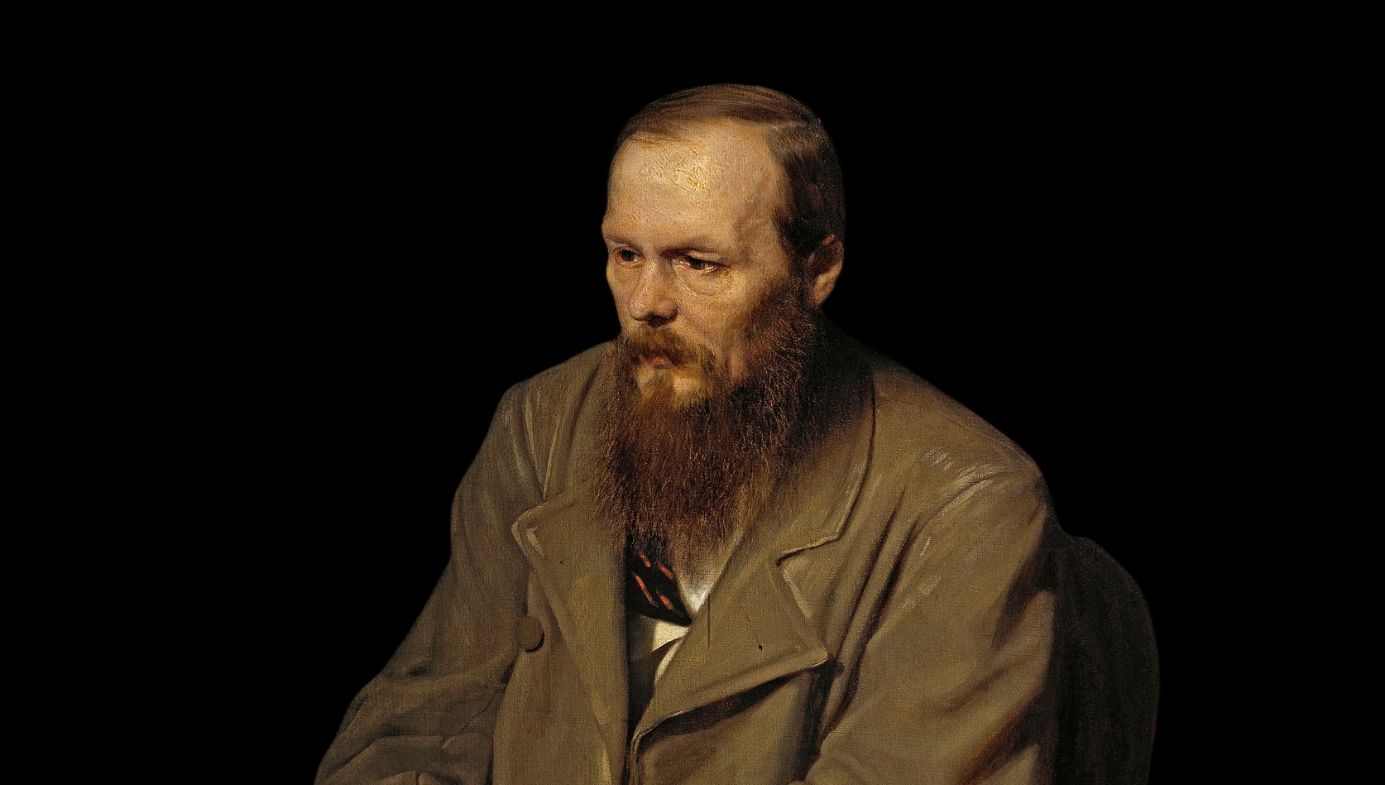

The individual described above is not Luigi Mangione, who was recently charged with murdering UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson, but Rodion Raskolnikov, the antihero of Fyodor Dostoevsky’s 1866 novel Crime and Punishment. Although Dostoevsky’s novel was published more than a century-and-a-half ago, the psychological, political, and even physical resemblances between Mangione and Raskolnikov are uncanny.

Like Mangione, Raskolnikov was an apprentice intellectual. Shortly before committing the murder of the “awful old harpy” Alyona Ivanovna, he wrote a law-review article titled “On Crime,” in which he argued that “extraordinary people” have the right to transgress traditional morality in pursuit of their ideals. As he explained during his police interrogation: “the ‘extraordinary man’ has the right … to permit his conscience ... to overstep ... certain obstacles, but only in the event that the fulfilment of his ideas (which may sometimes be salutary for all mankind) requires it.”

Luigi Mangione must have seen himself as one of Raskolnikov’s “extraordinary people.” The scrawled notebook found in his backpack denounces the American healthcare system. Fortunately, Mangione announces, a hero has arrived to challenge its rapacity, and he declares himself to be “the first to face it with such brutal honesty.” His manifesto apologises for any “strife or traumas,” but claims that “it had to be done. Frankly, these parasites simply had it coming.”

Some of the public appear to agree: a GoFundMe page suggests that Mangione “risked everything to stand up to corporations that are destroying American lives.” Images of “The Patron Saint of Adjustments” promote merchandise glorifying “St. Luigi.” There will no doubt be plenty of takers among the 41 percent of young Americans who deem the assassination “acceptable,” and especially in the crowd who have bestowed on Mangione the moniker of “People’s Justice.”

That name recalls the Narodnaya Volya, or “People’s Will”—the 19th-century Russian movement whose assassination of Tsar Alexander II in 1881 established them as the first modern terrorist organisation. They too believed that conventional moral law must be discarded in pursuit of a greater good. They were perfectly happy (some said joyful, a term also used by Taylor Lorenz to describe her reaction to Thompson’s murder) to sacrifice a few—or even a lot of—individual lives if they believed society as a whole would benefit. People must yield to principle.

This has been the revolutionary ends-and-means calculation ever since Brutus stabbed his beloved personal mentor, Julius Caesar. The Jacobins tried to guillotine their way to a Republic of Virtue. Leon Trotsky said the Bolsheviks would “put an end once and for all to the Papist-Quaker babble about the sanctity of human life.” Mangione may not have stumbled upon precisely those words during his late-night roams around the internet, but he will certainly have encountered words to the same effect.

Such words have never been hard to find. Another of Dostoevsky’s great novels, Demons, parodies a revolutionary theorist who “demands more than one hundred million heads for the establishment of common sense in Europe.” Readers might have laughed in 1871, when the book was first published, but they weren’t laughing by 1937. Once the sort of revolutionaries satirised by Dostoevsky seized power in Russia, some of his work was banned, and then they set about killing each other, just as his banned work had predicted.

The universal revolutionary idea—upheld by Robespierre, Lenin, Hitler, and now Mangione—is that the lives of “ordinary” people are worth less than those of “extraordinary” people. It is expressed by Friedrich Nietzsche’s figure of the “superman,” who violates his age’s inherited morality to accelerate “the transvaluation of values.” For Raskolnikov’s dichotomy between the “ordinary” and the “extraordinary,” we might substitute “sans-culotte” and “aristocrat,” “proletarian” and “bourgeois,” “Aryan” and “Jew,” “people” and “parasite.” It does not matter what makes the distinction, the point is that some lives are worth more than others as a matter of principle.

That is why Porfiry, the police detective in Crime and Punishment, is horrified by Raskolnikov’s article: “You uphold bloodshed as a matter of conscience,” he splutters: “This moral permission to shed blood … seems to me more terrible than official, legal licence to do so.” Raskolnikov believes that it can be morally right to commit murder if it benefits humanity en masse. To this, Dostoevsky offers the notion that human life is sacred, and as such, cannot be quantified. To take one human life is ethically exactly the same as taking one hundred million.

The concepts Dostoevsky protested are associated with the French and Russian revolutions. Yet they originate slightly earlier, in the utilitarianism of Jeremy Bentham. Bentham calculated morality mathematically, as the greatest good for the greatest number. Raskolnikov resolves to murder the pawnbroker when he overhears a student speculating with a logic typical of 19th-century Russian radicals:

Kill her, take her money and with the help of it devote oneself to the service of humanity and the good of all. What do you think, would not one tiny crime be wiped out by thousands of good deeds? For one life thousands would be saved from corruption and decay. One death, and a hundred lives in exchange—it’s simple arithmetic!

Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, this quantification of human happiness led to Malthusian attempts to reduce population, often rationalised by eugenics. It retains its revolutionary influence today among radicals on both the political Left and Right, and it translates the fictional act of Raskolnikov into the actual terrorism of Mangione. It appears, to those who espouse it and their admirers, as a liberating, revolutionary creed.

But Raskolnikov loses his reason the moment he commits murder. His conscience sinks its fangs into his psyche, and over the rest of the novel he is gradually consumed by feverish remorse. His intolerable guilt produces violent rages in response to the teasing, prodding inquiries of the ingenious Porfiry. Something similar already seems to be happening to Mangione. His angry and incoherent courtroom outbursts distort his once-delicate face into that of a raging primate. During his own penal servitude in Siberia, claimed Dostoevsky, he was always able to tell the murderers at a glance.

Although he makes perfunctory efforts to evade detection, it is clear that Raskolnikov wants to be caught. He confesses to his lover Sonya, incriminates himself to witnesses, blunders absurdly under interrogation. Above all, he writes an article rationalising murder immediately before committing his crime. Dostoevsky shows the impossibility of escaping one’s conscience, and Mangione’s erratic behaviour confirms it. He fled the scene but made no attempt to hide, he left a trail of evidence behind him, and he was apprehended eating at McDonald’s. And, like Raskolnikov, he wrote a manifesto.

The most obvious difference between Dostoevsky’s novel and today’s real-life scenario is that the only character who sees Raskolnikov as a hero is Raskolnikov himself. To the ordinary people he despises, he appears delusional, self-aggrandising, and pathetic. Even those who deemed Alyona a “louse” see murder for what it is—an immoral crime. Yet in our own day, a non-trivial proportion of Americans believe that the murder of Brian Thompson was “acceptable” because it accords with their own utilitarian calculus. They seem to be in the grip of what the great Dostoyevsky scholar Joseph Frank called the “embittered élitism” that, in Raskolnikov’s reasoning, “stressed the right of a superior individual to act independently for the welfare of humanity.” In Crime and Punishment, the antihero suffers through his emotional torment and eventually finds redemption—a propitious ending fitting for a 19th-century Russian novel. We are about to discover what kind of ending will prove fitting for the embittered elitism of 21st-century America.