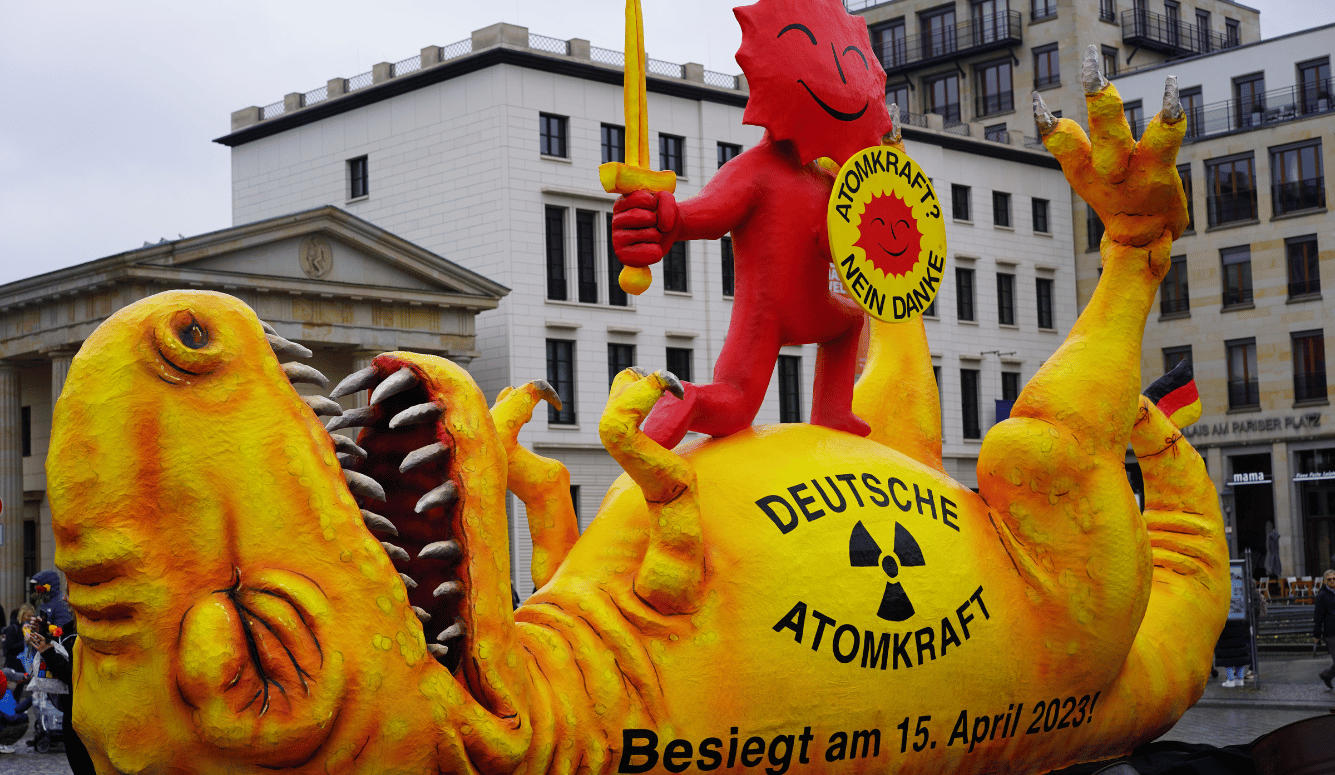

Under the leadership of its Green Party, Die Grünen, Germany closed its last nuclear power plants in 2023. The German economy was sent into a steep decline as electricity costs doubled and the country had to burn more coal and gas to make up for the lost energy. Given that nuclear power is the most effective method for reducing carbon emissions while growing the economy, and given that the Green Party insists that atmospheric carbon might lead to a civilisation-ending catastrophe, the ban on nuclear power is obviously counterproductive to the Greens’ own stated goals. The data that show nuclear power is safe are far more reliable than the aggressive interpretations of data required to predict mass death from global warming. Thus, the objection to nuclear power must be something other than its safety record.

I am a philosopher. When I teach ethics, I ask my students to study Marshall Sahlins’s theory of the original affluent society. Sahlins was an influential anthropologist who taught for many years at the University of Chicago. At a 1966 symposium, Sahlins argued that hunter-gatherers can survive on just a few hours of work each day. Our ancestors supposedly picked berries and nuts, hunted a little, and devoted the rest of their time to rest, social events, and arts. They were generous and not materialistic, because there is no benefit to avarice when you can only keep what you can carry. In his 1972 book Stone Age Economics, Sahlins compared this way of life with life in the modern, developed West:

For there are two possible courses to affluence. Wants may be “easily satisfied” either by producing much or desiring little. The familiar conception … makes assumptions peculiarly appropriate to market economics: that man’s wants are great, not to say infinite, whereas his means are limited, although improvable: thus, the gap between means and ends can be narrowed by productivity, at least to the point that “urgent goods” become plentiful. But there is a Zen road to affluence, departing from premises somewhat different from our own: that human material wants are finite and few, and technical means unchanging but on the whole adequate. Adopting the Zen strategy, a people can enjoy an unparalleled material plenty—with a low standard of living.

Sahlins clearly wanted to believe this account of the hunter-gatherer life. He based his conclusions on limited ethnographical evidence recorded decades before that examined the few remaining hunter-gatherer populations. But the accuracy of his claims is not my concern. What I ask my students to consider is this: assuming the hunter-gatherer life that Sahlins portrays is possible, is it a better life?

There are always a few students in my class who are excited by what I call the “Arcadian Vision”: the aspiration for a simple life given to the enjoyment of nature and unbounded hours of leisure untroubled by feelings of want or deprivation. The denizen of Arcadia is also our moral better, both for his (allegedly) harmonious coexistence with nature and for his ability to sustain a radically egalitarian society.

I have no moral objection to the Arcadian Vision, so long as it is chosen by those who attempt it. The problem is that many of those who long to live the Arcadian Vision also long to impose it on everyone else. They want to make you ride a bicycle to work and live in a smaller house and stop using air conditioning. And if we all pursued the Arcadian vision, we would almost certainly starve. But the Arcadian enforcers have an answer to this concern: if we encourage or require a reduction in the human population, then on a sparsely populated Earth all can enjoy the fruits of an egalitarian life of ease, in harmony with nature, in fifteen-minute cities.

As it began to emerge from Romanticism, environmentalism embraced the Arcadian Vision. William Blake’s complaint about “dark Satanic mills” expressed the Romantic longing for a world filled with grand purposes independent of human beings. William Wordsworth so strongly desired this re-enchantment that he would “rather be a pagan suckled in a creed outworn” than a child of the Enlightenment. What Blake and Wordsworth and the other Romantics could not fathom was that their preferred path would have led to far greater devastation of nature than the infernal factories.

When we lacked fossil fuels, we burned forests. In 1802, the year that Wordsworth likely wrote his sonnet, “The World Is Too Much With Us,” European forest cover was at its lowest point in centuries. The forests of Europe are more widespread and dense today than they were during Wordsworth’s time or Blake’s time, despite a population explosion. These Romantics denounced the progress that would return sylvan woods to the most civilised and densely populated place on Earth, all while making that quickly growing population wealthy.

The Arcadian Vision penetrates philosophy. Environmental ethics have been an active, if fringe, area of research for several decades now. But though some valuable work has been done, much of it has the de rigeur leftist and Romantic tropes that accompany the Arcadian Vision. The Left offer catastrophising predictions coupled with claims that we can save the environment by combatting some -ism or other (sexism, colonialism, racism, etc). And many philosophers and policymakers adopted the Romantic supposition that all indigenous people are wise stewards of the Earth who can instruct the rest of us.

Strong environmental ethics are founded on biocentrism—the value theory that more life is better than less life and that every living thing deserves some degree of moral respect. That does not require equal rights for mice and men, but it does entail that killing a mouse for no reason, or for malice, constitutes harm. For the biocentrist, the goal should be to foster greater flourishing of all kinds of life. This task is not helped by another diatribe about decolonisation, nor is it helped by requiring that our sciences incorporate “indigenous ways of knowing.”

Life is not harmony. Some people have suggested that life is an anti-entropy trick, but that is not true. We must eat to maintain the relative stability of our metabolism. We don’t escape entropy, we merely beat it back within our bodies by increasing entropy outside of our bodies. The Arcadian Vision encourages a false belief that there is some kind of steady-state equilibrium available in simplicity. Instead, life rides an entropy wave, stealing balance from the ever-increasing disorder in the universe. The sunlight that sustains us comes from a star fusing the last of its fuel. In a few billion years, the hydrogen will be exhausted, and the sun will expand and swallow the earth. Everything that remains alive here will die. That’s our universe. It isn’t kind or cruel, but it is indifferent. We alone can be the champions of life.

Long before the sun burns out, an asteroid may threaten to extinguish most of the life on our planet. If we all adopt the Arcadian Vision, we won’t even see it coming. If we continue to increase the power of our “dark Satanic mills,” we may be able to push that rock aside. Thus, everything depends upon this choice. The Arcadian Vision, if made universal, would be a suicide cult. We have to be able to respond to the diverse threats to all life that will inevitably arise, again and again.

These observations help to explain the widespread objection to nuclear power among environmentalists. Nuclear power creates problems, as every technology does. These problems are soluble, but the solutions require progress. For example, we can neutralise nuclear waste in fast reactors, or we can store it if we can continually improve our storage technology. Nuclear power is safe only if we continue to grow our technological abilities.

Alternatively, we can cling to the fantasy that solar panels or windmills can coexist with the Arcadian Vision—especially when they are shipped from unseen factories in China. Such a retreat is obviously not possible in a nuclear-powered future. This is why Die Grünen members hate nuclear power and why they banished it: nuclear power can provide abundant energy that will accelerate economic growth, and nuclear power requires a commitment to continual growth. To adopt fission is to turn your back on Arcadia.

The only way to serve life on Earth is to increase our understanding of the world and increase our technological abilities, so that we can afford to make this planet ever-more hospitable for life. Given enough time and wealth and knowledge, we can vastly increase the forests, repopulate the seas, defuse the stewing super-volcanoes, and bring back extinct species—all on a populous Earth.

If we strive and learn enough, humanity may even spread life on to other planets some day. This would arguably be humanity’s greatest achievement. If Homo sapiens turns out to be the only space-faring civilisation, it would be the greatest good ever done in the history of the entire universe. Any harm human beings have caused to life on Earth would be dwarfed by the accomplishment of bringing life to a dead world, where it could flourish for millions or even billions of years.

It is time to take environmentalism away from the environmentalists. They can pursue the Arcadian vision, and seek to live a less energy-intensive, less acquisitive life. We can applaud their efforts, the way we applaud anyone who accomplishes a difficult and unusual feat, such as running a triathlon or joining a monastery. But the business of life is life. The task for the rest of us is to learn and grow, to achieve ever-greater technological capabilities and to master ever-greater wells of energy, so that we can continue to cheat entropy and foster life on Earth and beyond.