Israel

After the Ceasefire

The new state of play in Israel’s ongoing war against Hamas, following the US-brokered ceasefire with Lebanon, the weakening of Hezbollah, and the fall of Bashar al-Assad.

The dramatic recent events in Syria have naturally attracted the world’s attention. But we should not allow them to detract from the importance of the Israel–Lebanon/Hezbollah ceasefire agreement reached on 27 November. That accord, which is designed to devolve into an open-ended armistice between the two sides, was a historic turning point in the war unleashed against Israel by Hamas, the fundamentalist Muslim rulers of the Gaza Strip, on 7 October 2023. The following day, the fundamentalist Lebanese terrorist organisation Hezbollah (the “Party of God”) joined the fray by rocketing northern Israel, which it continued to do for fourteen months, until this US-brokered ceasefire agreement came into effect.

The agreement calls for a cessation of fire by both sides for a sixty-day period, the withdrawal of IDF and Hezbollah forces from south Lebanon, the latter to areas north of the Litani River, some 30 km from the border with Israel, and the return of civilian inhabitants displaced by the fighting to their homes on both sides of the border. During this period, the Lebanese Army is to be deployed between the Litani and the international frontier to assure the evacuation of the IDF and of Hezbollah and its armaments from the area. Hezbollah is to be demilitarised—and prevented from re-arming in future—under the supervision of an international committee headed by the United States.

The agreement, which was publicly welcomed by Hezbollah’s backer, Iran, failed to include a demand for the cessation of Iranian-orchestrated rocket and drone fire against Israel by Iran’s proxy militias in Iraq, Syria, and Yemen. These proxies have continued to pepper Israel with occasional long-range suicide drones and missiles over the fortnight since the ceasefire went into effect. And Iran has continued to threaten that it will strike at Israel in retaliation for the Israel Air Force (IAF)’s devastation of strategic Iranian sites back in October. That account remains open.

There is also an ongoing war in the Gaza Strip and there remains the problem of Hamas’s continued incarceration of more than 100 Israeli hostages—probably only half of whom are still alive—kidnapped during the 7 October assault on southern Israel that triggered the regional Middle East war. Israel countered that assault with a massive air and ground offensive into the strip and the IDF currently occupies parts of the territory, but Hamas retains effective control—through financial means, terrorism, and local popularity—over much of the strip’s population of 2.3 million. Recent contacts made via American and Qatari mediators have encouraged hopes that an Israeli–Hamas ceasefire and prisoner–hostage swap may soon be in the offing—an event that US president-elect Trump has demanded take place before his inauguration on 20 January 2025.

Over the course of the year following 8 October 2023, when Hezbollah began rocketing northern Israel in solidarity with Hamas, the Lebanese terrorist group consistently stated that it would only cease fire if Israel ended its counteroffensive against Hamas and withdrew its forces from the Gaza Strip. But in October 2024, following Israel’s highly effective counteroffensive against Hezbollah that began the previous month, which claimed the lives of thousands of Hezbollah fighters, including those of most of its senior commanders as well as of the organisation’s legendary leader, Sheikh Hassan Nasrallah, his successors and their sponsors in Iran decided to cut their losses and salvage what they could, and severed the Lebanon–Gaza Strip linkage. Following the ceasefire in the north, the severely-mauled Hamas have been left to carry on the fight against Israel alone—a situation that has no doubt deepened the general pessimism among the Palestinian people, who have felt abandoned by the world since 1948.

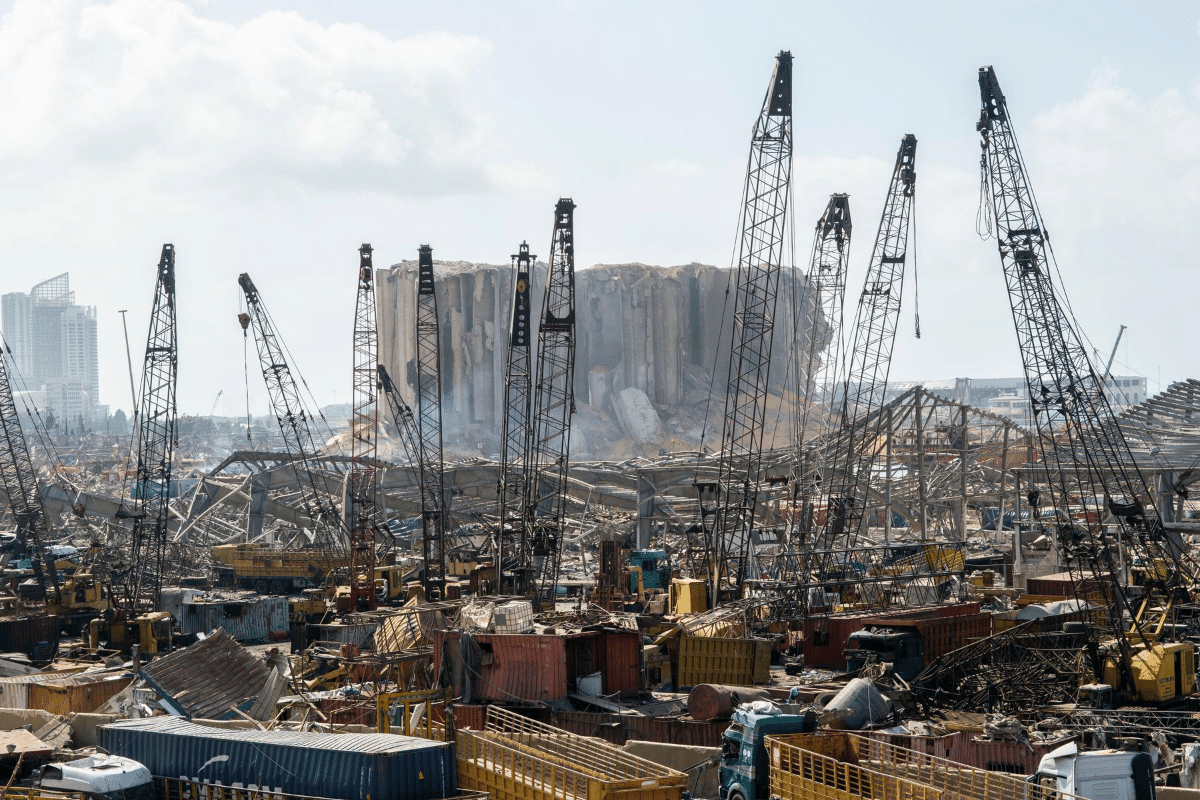

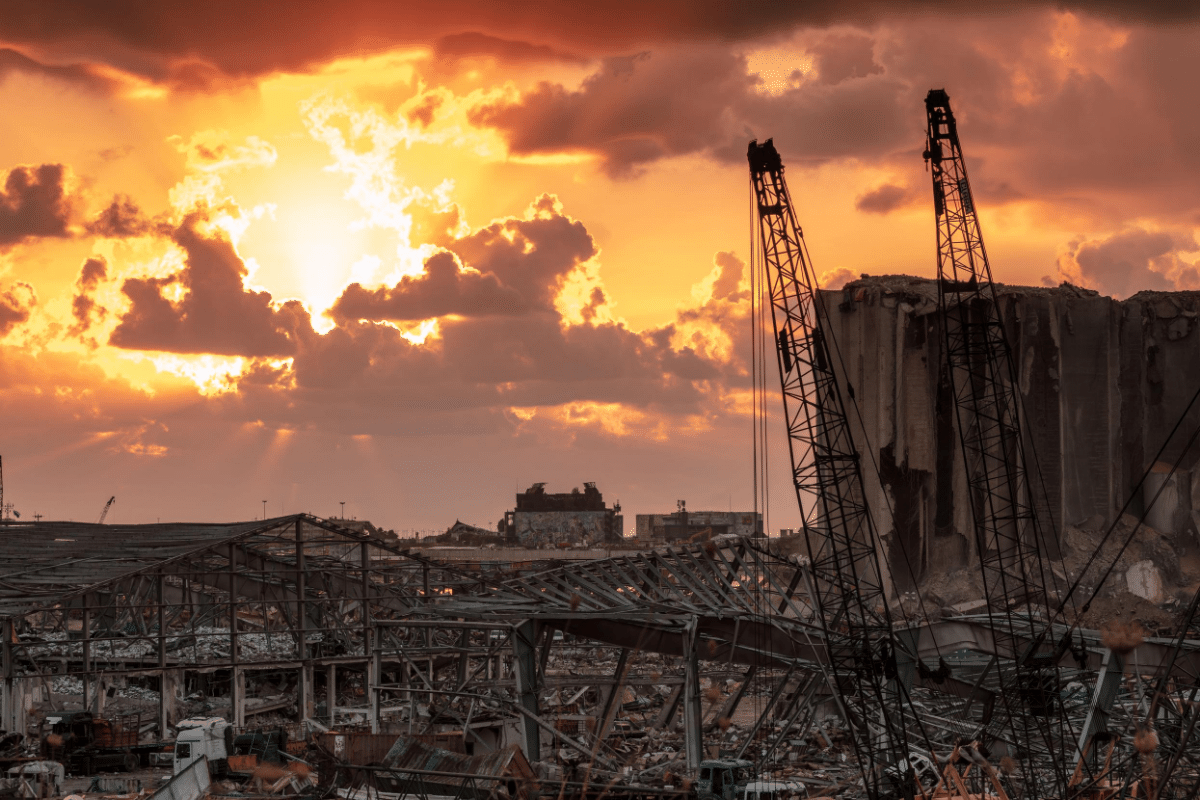

The Lebanese government and people were eager for the deal, however, because the war uprooted more than a million Lebanese from their homes, not just from the embattled south but from the eastern Bekaa Valley and the southern neighbourhoods of Beirut, areas that were repeatedly bombed by the IAF. According to Lebanese government estimates, the war also caused some $10US billion worth of damage. For Hezbollah, the ceasefire has provided a welcome reprieve from the Israeli onslaught. According to the IDF, Israel has destroyed 70–80 percent of Hezbollah’s extensive rocket stockpiles, including most of its medium- and long-range rockets, which explains why so few of those rockets have hit Tel Aviv over the past months. It was, above all, the fear of possibly devastating rocketry that stayed Israel’s hand from fully assailing Hezbollah until September 2024. When the assault was finally undertaken, the IDF—and probably Mossad, which likely engineered the exploding pager campaign—performed much more effectively than the Netanyahu government had anticipated.

So far, the Israel–Hezbollah ceasefire appears to be holding. But Israeli drones continue to patrol the skies above Lebanon and Israeli jets have attacked Hezbollah personnel and positions daily, arguing that the organisation is in breach of the ceasefire stipulations. The much-degraded Hezbollah, fearful of a resumption of full-scale hostilities, has so far refrained from firing into Israeli territory or at Israeli ground forces, which, since 1 October 2024, have occupied a stretch of southern Lebanon along the international frontier. But Hezbollah has tested Israeli resolve by trying to hide its operatives among the civilian returnees heading for their homes in southern Lebanon. The IDF has identified and either killed or captured about a dozen such infiltrators over the past fortnight and has warned Lebanese civilians not to try to reach their villages along the international line. Tens of thousands of south Lebanese villagers therefore remain stranded, still awaiting permission to return to their homes, many of which were destroyed during the fighting. In addition, hundreds of thousands of evacuees from Beirut’s southern neighbourhoods—especially the devastated Dahiya quarter, Hezbollah’s headquarters—and from the Bekaa Valley of eastern Lebanon, another Hezbollah stronghold, still cannot go home because of the devastation. Similarly, the 60,000 Israelis displaced from the country’s border-hugging settlements on Israeli government orders are only just beginning to trickle back. Many hundreds of their homes were destroyed or substantially damaged by Hezbollah rockets and drones over the past fourteen months.

For the past two weeks, the IAF has been continuing its efforts to prevent Hezbollah from re-arming. It has bombed vehicles trying to cross from Syria, suspected of carrying Iranian weapons and ammunition bound for Hezbollah, and killed the Iranian and Hezbollah agents involved in the arms transfers in their Damascus hideouts. But although the Israeli–Hezbollah ceasefire remains shaky, both sides are committed to its maintenance.

But the deal has a number of inbuilt problems that may ultimately undermine its longevity. First, it forbids Hezbollah from rebuilding its arms-production facilities, something that will be difficult to monitor or control. Second, and more importantly, the deal’s explicit reference to UN Security Council resolution 1701 of 2006—issued after the last major Israeli–Hezbollah clash, which Israelis refer to as “the Second Lebanon War”—commits the thus-far ineffectual Lebanese government to disarming Hezbollah: the deal refers to “disarmament of all armed groups” except for the state’s own security agencies. And third, the deal charges the Lebanese Army and UNIFIL—the UN force installed in southern Lebanon in 1978, to protect northern Israel from Lebanese “hostiles”—with preventing Hezbollah from sending its forces southward to the border with Israel. But over the years 2006–23, neither the Lebanese Army nor UNIFIL managed to keep Hezbollah out of southern Lebanon.

Many of the 60,000 displaced Israeli villagers are reluctant to return home for fear that UNIFIL and the Lebanese Army may once again fail to take effective action, allowing Hezbollah forces to return to southern Lebanese villages and resume rocketing Israel. Indeed, the announcement of the Israeli–Lebanese–Hezbollah deal met with profound scepticism in Israel. But Benjamin Netanyahu and the IDF commanders have promised that this time things will be different, that Israel will not rely on either the Lebanese or UNIFIL and will respond decisively to any Hezbollah provocation or infringement. But, given what happened in the south on 7 October 2023, many Israelis no longer trust either Netanyahu or the army.

Be that as it may, in an unpublished American “side-letter” to the Israel–Lebanon agreement, Washington apparently endorses Israel’s “right to defend itself,” which Israel has interpreted as carte blanche to fire back in response to any Hezbollah violation of the accord, however small. The letter also appears to explicitly back Israel’s right “to conduct reconnaissance flights over Lebanon” for intelligence purposes (“so long,” it reportedly says, “as they do not break the sound barrier”). More generally, the “side-letter” apparently makes the rather vague commitment that the United States will help Israel “to prevent Iran from destabilizing the region” and thus undermining the Israel–Lebanon deal. France, a traditional protector of Lebanon, was also involved in hammering out the Israel–Lebanon deal—after Israel okayed its participation as a reward for the French announcement that it would not honour the recent International Criminal Court decision to arrest Netanyahu and his former Defence Minister Yoav Gallant for war crimes committed in Gaza. The court’s ruling is supposed to be implemented by all 124 signatories of the Rome Statute, of which France is one.

Iran has publicly “welcomed” the agreement and apparently strong-armed Hezbollah’s remaining leaders into accepting it. Tehran, which controls Hezbollah’s purse-strings and is its main political backer and arms supplier, has probably cautioned the Lebanese organisation not to provoke Israel over the coming months—or possibly year—to give the organisation time to reorganise and re-arm. But the surprising fall of the Assad regime in Syria last weekend has probably nullified any such Iranian expectations or hopes. Syria will no longer serve as a ready conduit for Iranian arms and other supplies to Hezbollah. And, given its weakness, Hezbollah, which exercised a stranglehold over Lebanon and Lebanese politics for decades, may no longer serve Iran as an effective deterrent.

Iran had hoped that the possible activation of Hezbollah’s tens of thousands of rockets would deter Israel from attacking Tehran’s pet nuclear arms project. Netanyahu seems to have hinted at a possible Israeli strike against the Iranian nuclear facilities in his speech on 27 November, when he gave three reasons for Israel’s acceptance of the somewhat unclear Israel–Lebanon deal. He referred to the goal of isolating Hamas; to American delays in supplying Israel with arms and munitions; and to the “Iranian threat.” Indeed, he placed “Iran” at the top of the list—in a barely-veiled hint that, now that the war with Hezbollah is over, Israel is free to pursue the goal of destroying the Iranian nuclear installations.

Netanyahu’s reference to the delays in arms shipments was seen by most Israelis—and certainly by Washington—as an ungrateful slap in the face of the Biden administration, which has been a firm supporter of Israel throughout the 14-month long war, providing both munitions and political cover, especially at the UN Security Council, which could theoretically impose sanctions against Israel.

What the Americans have supplied Israel with and when over these past fourteen months remains a secret. It is true that Washington has held back at least one shipment of quarter-tonne and one-tonne dumb bombs. But Netanyahu’s complaint hints at a graver problem: Israel has used up vast amounts of munitions, leaving its stockpiles severely depleted, especially of the Tamir missiles used in the Iron Dome anti-missile batteries and of air-to-ground missiles. The Iron Dome batteries managed to shoot down almost 90 percent of the Hezbollah and Hamas rockets and its Hetz (Arrow) long-range missiles brought down most of Iran’s and the Houthis’ ballistic missiles—actions that saved countless Israeli lives and buildings. Moreover, the IAF’s mainstay F-16 and F-15 fighter-bomber squadrons and its Apache attack helicopters, almost none of which are of recent vintage, are probably in need of both replenishment and a long breather for major maintenance overhauls, having just flown many thousands of sorties over Lebanon, Gaza, Syria, Yemen, and Iran.

Meanwhile, with the probable help of American mediators, Israel and Lebanon are to renew talks about “frontier” adjustments, as demanded by Lebanon and Hezbollah and vaguely iterated in the Israel–Lebanon agreement. The Lebanese claim that Israel is illegally occupying a few hilltops and gulleys along the two countries’ 81 km frontier. The frontier was demarcated in 1923—though not with complete accuracy—by the two League of Nations Mandatory powers—France, which then ruled Lebanon, and Great Britain, which ruled Palestine—and confirmed in 1949 by the Israel-Lebanon General Armistice agreement that ended the first Israeli–Arab war.

These developments in the north are now indirectly affecting events in the south. In Israel, relatives of the 100 hostages, backed by much of the Israeli public, have persistently campaigned for a Hamas–Israeli deal that would see the hostages released in exchange for thousands of Hamas fighters currently in Israeli prisons. Hamas continues to demand that the deal also include the stipulation that Israel stop the war and withdraw all its forces from the Gaza Strip. But with the fall of the Assad regime and the consequential weakening of Iran and Hezbollah, Hamas may now be more amenable to a deal. Netanyahu continues to press for at least a partial, open-ended Israeli occupation of parts of the strip, while Netanyahu’s religious coalition allies demand that Israel bolster its hold on the strip—or at least its northern end—by re-establishing Israeli settlements in the area, settlements abandoned by Israel in 2005, when it also pulled the IDF out of the Strip. Should there be no consolidation of an Israeli–Hamas deal, the Israel–Lebanon deal will free up many Israeli soldiers, now deployed in the north, for renewed offensive action in the Gaza Strip and ease the burden on IDF reservists, who have been serving long stints in the military and who will soon be allowed to return to their homes and businesses.