Settler Colonialism

A Fashionable Madness: The Obsession with ‘Settler Colonialism’

The works of literary critic Adam Kirsch and of novelist and memoirist Joan Didion provide a salutary rebuttal of settler colonialist theory.

A review of On Settler Colonialism: Ideology, Violence, and Justice by Adam Kirsch, 160 pages, W.W. Norton & co. (August 2024).

According to legend, in around 1626, Dutch trader Peter Minuit arranged the purchase of what came to be known as Manhattan by the New Netherland company for “24 dollars’ worth of beads and trinkets.” Historians have long considered the transaction just one—albeit especially significant—item in a long inventory of dispossession and displacement of natives by settlers in the New World. This history has more recently become the focus of public consternation. In its official land acknowledgement, for instance,

New York University acknowledges that it is located on Lenapehoking, ancestral homelands of the Lenape people. We recognize the continued significance of these lands for Lenape nations past and present, we pay our respects to the ancestors as well as to past, present, and emerging Lenape leaders…. We believe that addressing structural Indigenous exclusion and erasure is critically important and we are committed to actively working to overcome the ongoing effects and realities of settler-colonialism.

Yet attempting to generalise from patterns of European settlement in North America to other regions with distinct histories often produces absurd and catastrophic delusions, as Adam Kirsch argues in his new book, On Settler Colonialism.

I am a descendant of Protestant Europeans who came to North America in the 1700s. But according to the precepts of settler colonialism, I remain as much a settler as my English and Scotch–Irish ancestors or their German, Polish, and Lithuanian immigrant followers and will bequeath my settler colonialist status to my children and their future offspring. As Kirsch notes, adherents of this view include many young people in the West, for whom the stain of colonial settlement is ineradicable and bone deep. But how different are the descendants of settlers who arrived on distant shores decades or centuries ago from natives whose ties to the land date back millennia?

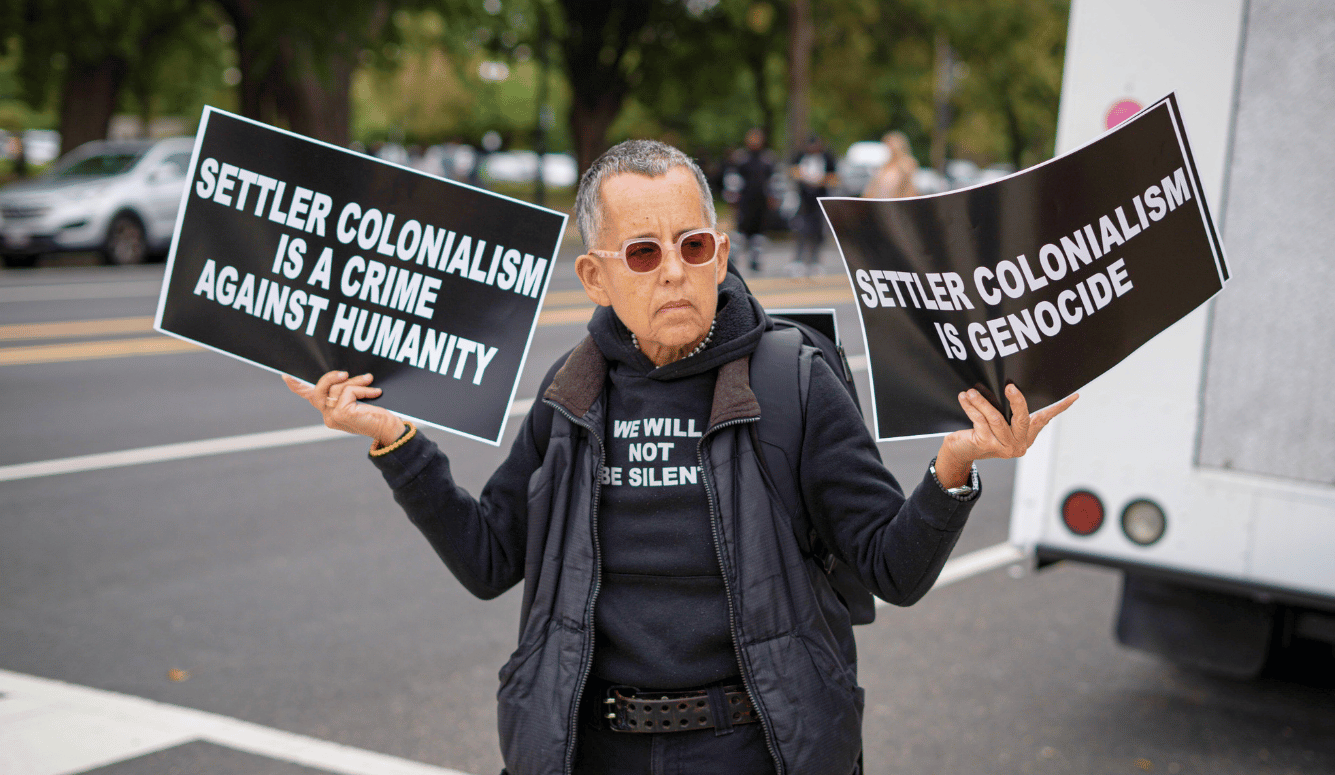

Kirsch’s book delineates “a political theory of original sin,” a secular theology that demands repentance but allows no forgiveness. His account offers a timely critical analysis of a strangely seductive welter of ideas that has moved from the academic fringes to the progressive mainstream. As Kirsch writes, to describe a society as “settler colonialist” is an attempt to completely delegitimise its claims to permanence. It implies that settlers are intruders whose presence was imposed upon “the people previously living there” against their will and at their expense. The problem is not that the theory’s claims about the past are inaccurate—often they are broadly true, though they oversimplify complex historical developments. The problem is that this is not just about history. The underlying agenda of the proponents of this theory is to change society in the present and future. Settler colonial theory distinguishes itself from standard historical revisionism by its ideological—even eschatological—ambition to reverse history.

At the heart of settler colonial theory is a linguistic equivocation. “Settler colonialist” is a congealed term made up of two words with distinct valences. A settler lands in a particular place and decides to remain. A colonialist dispossesses others of their rightful territory and supplants them. Therefore, a “settler colonialist” is both neutral and malign: someone who does something that is not bad in itself in an especially bad way. Historically, there may be some truth to this. But there is a noticeable reluctance among academics to apply the label to non-Western societies or regimes of the Left. This tendentious usage renders it slippery and ambiguous. “Settler colonialism” can be readily used as a smear against large and powerful Western countries such as the United States, Canada, and Australia, as well as against small but relatively powerful states seen as aligned with the West, such as Israel. But it is rarely applied to nations like China, Russia, Iran, Cuba, and Venezuela, whose histories are similarly premised on imperial expansion or colonial dominion. Such a deliberately weighted concept has little value beyond providing a way to place a rhetorical thumb on the scale.

The founders of settler colonial theory probably intended this. As Kirsch writes, their aim was “to condemn every possible relationship between settler and native” by substituting resentment and animosity for peaceful coexistence—coexistence based, as they saw it, on oppressive social structures. Initially, Australian and North American academics within the disciplines of anthropology and sociology probably hoped to create a revolutionary vanguard out of the remnants of dispossessed native peoples. Yet the question of how minuscule indigenous populations (who make up only 3 percent of the population of Australia, for example) could overcome settler societies that had expanded to fill a continent had no obvious answer.

The original inspiration for settler colonialism theory, when it first developed in the 1970s, was a strain of third-world Marxism. According to early theorists such as Kenneth Good, the cause of dispossessed indigenous people could motivate political movements that would abolish private property and reverse the timeline of capitalist development in colonised nations such as Rhodesia, Algeria, and South Africa. But the theory was soon put to other uses. Settler colonialism was brocaded into cultural critique. Threats to indigenous people were no longer limited to territorial sovereignty or physical survival; they included cultural and linguistic assimilation.

Adherents of this outlook sometimes seem partially aware that they have enlisted in a lost cause. As Kirsch writes, “Its impossible goal is to turn the clock back to the world that existed before 1788 or 1607 or 1492.” According to Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang, this involves “relinquishing settler futurity,” meaning literally dispossessing the 98 percent or more of the US population of non-indigenous origin of their ill-gotten gains. As Kirsch dryly observes, this unlikely goal “removes the ideology of settler colonialism from the realm of politics,” and explains its limited appeal to the people “it claims to vindicate.” Settler colonial theory is, in short, a paradigmatic example of elite capture of a social movement—that of indigenous peoples for greater sovereignty, recognition, and equal rights.

The indigenous rights movement emerged in the 1960s alongside other civil rights and anticolonialism movements. Settler colonial studies was institutionalised as its academic manifestation in the West. As with other radical social movements, this institutionalisation led to a shift away from direct political action to post-materialist activism centred on scholarship, artistic expression, and pedagogy. The change of emphasis altered the aims of the movement itself. Joan Didion has memorably written about a similar transformation within feminism:

More and more, as the literature of the movement began to reflect the thinking of [those] who did not understand the movement’s ideological base, one had the sense of this stall, this delusion, the sense that the drilling of the theorists has struck only some psychic hardpan dense with superstitions and little sophistries, wish fulfillment, self-loathing and bitter fancies. To read even desultorily in this literature was to recognize instantly a certain dolorous phantasm.

The “dolorous phantasm” to which the feminist movement reduced its object was the universal victim in one of many guises. This transformation of a social movement into an ideological fantasy-scape did not further material progress for women. Instead, it encouraged psychic and political regression. As Didion scathingly chronicled, social movements tend to dissolve into wishful thinking and revenge fantasies when subjected to the tender mercies of elite sympathisers with the oppressed. As the Australian historian Fiona Paisley has noted, the history wars over colonial settlement primarily reflect a crisis in white identity. Kirsch observes that “a similar point can be made about the discourse of settler colonialism in the United States. It is primarily a conversation among ‘settlers’ about their own identity, and what it offers is less a program for action than a political theology.”

As Kirsch notes, the rhetoric of sin and redemption often resounds in settler colonialism discourse, “even when writers themselves aren’t fully conscious of it.” One of the field’s luminaries, Lorenzo Veracini, describes the goal of his work as “to kill the settler in him[self] and save the man.” Kirsch also highlights another peculiar rhetorical habit common among the field’s practitioners, including Veracini—a regular recourse to metaphors of violence to describe the prospect of decolonisation. Kirsch detects in Veracini’s formulation an echo of the anticolonial theorist Frantz Fanon, who celebrated redemptive murder in the following words (in Kirsch’s translation): “To work means to work toward the death of the colonist.” And what if the colonist happens to be a descendant of Jewish refugees residing in a small country in the Middle East? Well then, no one ought to accuse the colonised who are seeking to drive out their oppressors of antisemitism—even when they borrow freely from ideological perspectives infused with it.

Like many other theorists, Veracini finds settler colonialism at its most unrepentant in Israel and in the United States. This pairing recurs frequently. Mahmood Mamdani refers to the United States and Israel as the exemplary “settler-colonial nation-state projects.” In The Routledge Handbook to the History of Settler Colonialism, Kirsch points out, “Israel is the subject of three separate chapters… more than any country except the United States, which gets four.” Either these two nations distinctively embody the many evils of settler colonialism past and present or something else is at work. As Kirsch points out, there are obvious historical differences between the fate of the indigenous peoples of the United States and those of Israel/Palestine, whose claims to indigeneity rest on very different arguments and depend on very different sources. Palestinian Arabs inhabited the Ottoman territory roughly equivalent to today’s Israel, Gaza, and the West Bank—but so did other ethnic and religious groups, including Jews. Furthermore, many of the arguments for Palestinian nationhood rely in part on religious claims of Muslim sovereignty over specific places, such as Al-Quds (Jerusalem) and its Dome of the Rock. Jewish zealots make similar territorial claims to Judea and Samaria. Imagine the land acknowledgements.