Art

Podcast #254: In Defence of Beauty

Iona Italia talks to artist Megan Gafford about how we have come to value statement-making over beauty and craftsmanship in art and architecture.

Introduction: My guest this week is Megan Gafford. Megan is an artist, teacher, and writer. She publishes visual essays on her Substack “Fashionably Late Takes.” She is also a frequent contributor to Quillette. In this conversation, we discuss her recent long thinkpiece for the magazine, “The Totalitarian Artist: Politics vs Beauty.” Among other topics, we look at the way in which Marcel Duchamp and the other modernists revolutionised art; at the modern art market; at how artists and critics have moved away from a celebration of beauty and skill and towards art that is conceptual and often polemical. We also look at the impacts of these changes on architecture, with special reference to the decline of Art Deco. I hope you enjoy my conversation with Megan Gafford.

Iona Italia: Hello, Megan. Thank you so much for joining me. I’m going to begin by just reading the first couple of lines of your piece for Quillette, which is about the connection between failure in art and totalitarianism. You write,

Hitler became the butt of a joke: a failed artist with a funny moustache. But we rarely ask ourselves whether there is an equivalent example of a leftist whose totalitarian personality emerged, in part, because the world shrugged at his bid for creative genius.

This was no idle question for Eric Hoffer, a philosopher of totalitarianism who helped shape the worldview of American presidents He saw the totalitarian impulse as a temptation for failed artists of every political persuasion. He writes:

“The man who wants to write a great book, paint a great picture, create an architectural masterpiece, become a great scientist, and knows that never in all eternity will he be able to realize this, his innermost desire, can find no peace in a stable social order—old or new. He sees his life as irrevocably spoiled and the world as perpetually out of joint.”

So, can you tell me why you begin this piece on art with a philosopher and historian of totalitarianism like Eric Hoffer and where you see the connection between this idea beyond Hitler himself?

Megan Gafford: (01:57.117): Yes. So, Eric Hoffer is a very celebrated philosopher of totalitarianism. He’s been celebrated by people from the Left and the Right. And some have gone so far as to call him a genius. And in his most famous book, The True Believer: Thoughts on the Nature of Mass Movements, he pays special attention to artists, specifically failed artists. And if someone had asked me what kind of person a philosopher of totalitarianism ought to be preoccupied with off the cuff without having thought about it before, I might assume, well, a politician, somebody like that. But no, he pays more attention to artists and people with a frustrated creative impulse that they can’t satisfy. So because he is such a big deal in the philosophy of totalitarianism, I don’t think that artists can ignore his allegation that when we fail, we pose a special risk to society. And I think that artists need to take that seriously and confront this allegation.

II: (03:03.512) So, one of the connections that you make in the essay, which I found fascinating, is the idea that when art moved towards postmodernism, artists no longer ... the art world and art critics no longer valued aesthetic beauty and artistic skill and craftsmanship and also allusions to tradition as highly and instead that leftist artists who yearned to create something meaningful were left with only one option, which was to try to find meaning in the political message they were conveying with their art. I thought that was a fascinating idea. Can you tell me more about that?

MG: (03:55.369) Yeah, so this famously started with the father of contemporary art, Marcel Duchamp, who famously presented a urinal as artwork in 1917 and very emphatically made the point that now anything, even a urinal, can become art. And art developed a more irreverent and ironic tone. To be earnest, like the more romantic painters from the prior centuries, would get you sniggered at. And there was this general sense of ennui and jaded disillusionment that—although Duchamp himself was not a terribly political person—he channelled in a kind of jokester-esque way. And that changed the art world ever since. So, for about a century now, if you want to be earnest and you want to be sincere, then there needs to be a political edge. Most artists can’t quite get away with it otherwise. Some of the best contemporary artwork that we have now often uses people’s identities and identity politics as a vessel for sharing that meaning. So you get some meaningful political artwork.

II: (05:12.029) Could you give us a couple of examples of what you think is more meaningful among those modern artworks?

MG: (05:22.729) Yeah, so I think my favourite contemporary art piece is Teresa Margoles’ In the Air. She’s a Mexican artist and she’s presented a few iterations of this. I think the first one was in 2003. She filled a museum with bubbles, which seems very whimsical, but the bubbles were made from wash water coming from the Mexico City Morgue. So, once you take a moment to read the wall text for this artwork, all of a sudden you realise that these bubbles popping on your arm came from washing a dead body. And specifically, these are the bodies of people who died in a drug trade that had wrecked her own home in Mexico. And she really wanted people to feel her sorrow with her. So it’s controversial. A lot of people thought it was grotesque. I thought that the grotesque aspect just made it more sublime, that you have this tension, this push and pull: you’re attracted to the whimsy of the bubbles and you’re revolted by the idea of something tainted by death. The water was sanitised, but still, there’s an ick factor. You get this complicated emotional experience with the piece. So I like that. Maybe I have a morbid personality, but I like that kind of tragedy in art.

I’ve actually never seen the piece, but that’s one of the funny things about a lot of contemporary, or at least a lot of conceptual art, is you don’t have to actually see it to appreciate it. Another example that I have not seen in person, but it’s one of my favourite contemporary art pieces is by Félix González Torres. He was a gay man living in New York City who died of AIDS. And in the eighties, his partner was dying of AIDS before him. When his partner got diagnosed with AIDS, he put two commercial clocks on the wall, just touching, like a kiss. And they’re set to have the same time, but over the course of this exhibition, the time with these clocks fell out of sync. And this was meant to symbolise the way one of their heartbeats is going to falter first. He just yearned to be with this man he loved forever and the time was slipping away.

So, again, you have this tragedy, but the piece itself is just two commercial clocks. You can imagine it. You don’t have to actually see it. Again, it’s a conceptual art piece. It’s mass produced. The sculptor’s touch is totally irrelevant at this point. Maybe the piece would have been better off as a poem, but he made it into a conceptual art piece.

II: (08:13.729) Yeah, I think that’s fascinating. The way in which in a lot of contemporary art, the curator’s words in the little explanation, in those explanations that they stick on the wall next to the piece, that’s often more important than the piece itself. And in fact, you’re not really able to or perhaps even expected to get anything out of the piece unless you read the explanation. So, the explanation becomes in a sense the artwork and the artist’s contribution is simply the concept.

MG: (08:59.677) And curators became very important in this era. So that’s a good insight. And what you just said got me thinking about the difference in the experience you have of walking through the Metropolitan Museum here in New York, where I am, versus MoMA, Museum of Modern Art, where if I’m walking ... I mean, it depends on how much you know about our history, this could affect your movements. But let’s say you don’t know much about our history and you’re walking through the Met, you might not ever want to take time to read any of these didactic statements about the artwork. You’re too busy looking at it. If you stop and read all the wall statements, how are you going to have time to see more beautiful artwork? But if you go to MoMA and you’re looking at a lot of this modern and postmodern contemporary artwork, and if you don’t already know the art history, then you definitely need to sit there and read those wall statements. So the way you move through the museum entirely changes depending on if it’s this modern art that’s meant to be thought about. Duchamp talks about he wanted to remove art from being retinal, from being something that we look at and give it to the blind.

II: (10:09.59) In other art forms, it’s impossible to imagine that working in quite the same way. For example, I used to be a professional dance teacher, as many people know, and you couldn’t substitute a dance performance with a description of the performance. Of course, there are similar tendencies in dance, there’s also postmodernism in dance, in which, in some performances, people are no longer doing movements that require a lot of dance skill, but are just doing ordinary movements or very minimal movements or just standing there and things. I’m not terribly fond of that school of dance, but at least we don’t replace it with a description.

A friend of mine [Mark Ledwich], in 2018, went to the Queensland Art Gallery in Brisbane, where they had an exhibition of blank canvases. And he wrote a little piece about this. It was by Robert Rauschenberg, it’s called “White Painting.” I think it had come from the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

And my friend says, “There should be a name for the feeling of rage when you see what normal folks call modern art. And I feel it intensely.” There was a really long explanation on the wall about all the things that you could find in the piece if you were sensitive enough and philosophically keyed in. And one of the explanations says, one of the things written by the curator, I’m quoting the curator here, “It’s tempting to look at one of these paintings and think some jerk just took a tube of white paint and spread it on a canvas, but it’s not actually that easy. There are a lot of subtle intricacies that make it more than just a white canvas.” And my friend writes, “I reject both of these reasons. This reasoning seems like a rationalisation. This explanation also applies equally to the white wall behind the painting. I want to know the real reason why I’m being assaulted with this spectacle of nothingness” at taxpayer expense. I think that’s a very normal response. And although I’ve studied art a little bit, I have the same response as he does. I don’t need to and want to see an exhibition that is simply white canvases.

MG: (13:17.127) Yeah, the most famous one that I know of like that is Malavich’s “White on White.” So it’s like a slightly askew white square on, it’s a slightly different shade of white on the back of another one. I’m curious now how many white canvases are out there. And enough warnings of it. When I was an art student, I was never drawn to that kind of art, but ... and I think this is common for a lot of our students, you feel like it’s your fault for not getting it. And you need to work harder to understand modernism and postmodernism and all the various ways people try to define these movements, these eras. If only you can get through enough convoluted Judith Butler-esque prose, then you’ll finally be smart enough to figure it out. And it was a long time before I just decided maybe I finally felt educated enough. I became a university lecturer myself, and finally came around to thinking it’s a bunch of bullshit. That what Duchamp did: he injected what I think Hoffer correctly described as a totalitarian psychology into the art world.

Again, Duchamp himself wasn’t a very political person. He’s the most famous member of the Dada movement. And that movement itself had a lot of radical leftist ties, but he himself wasn’t super political. But he created this irreverence. And he called it “anti-art.” He really, I think, tried to destroy art, perhaps.

He said some contradictory things in interviews throughout his life. And people have different takes on how strongly he felt about disliking art. He sometimes likened art to religion and he meant that in a bad way. So, I don’t know if I would go so far to say that he wasn’t an artist. I like his “Nude Descending a Staircase,” the one painting of his that’s famous, but he was certainly a dastardly artist, an artist who did great harm to art. And we still haven’t quite gotten past it, even though we’re past the age of the artist manifestos, you’ll be snickered at for that too if you try to make a manifesto nowadays, which were very popular in his time.

II: (16:00.29) Thank goodness.

MG: Yes, thank goodness. And things aren’t as bad as they were in the 20th century when it comes to the way art has been scarred by Duchamp. In my essay, I strike a more positive note that we’re due for a renascence, we’re due for people to try to fight against this—not necessarily even fight, but just disregard this and move past these Duchampian ideas. And people have to varying degrees.

A very famous art critic, Dave Hickey, back in the 90s, declared that the 90s were going to be the decade of beauty. That was going to be the issue of the 90s. And it was very controversial at the time, because here we are at the very end of the century where beauty had been abandoned. And then 10 years after that, another famous art critic is still kind of wincing about like, “I feel a little sheepish,” he says, “I feel sheepish talking about beauty.” And he’s a philosopher of aesthetics. A 21st-century philosopher of aesthetics is sheepish about talking about beauty. That was in 2003 when Arthur Danto, that famous philosopher of aesthetics and art critic, talked about being sheepish about beauty. So, here we are about 20 years later, and we are in another politically charged time, and political art or identity politics art is very ascendant right now. But there’s some whispers that we might be past “peak woke.” And maybe now is the time where acting like Duchamp isn’t cool anymore and political art has become tedious enough where we can have a little bit more beauty again.

II: Yeah, there was a movement, I guess it started after the First World War, and people justified it by saying that the war itself, the First World War and then the Second World War, had been so uniquely horrific, such uniquely horrific experiences, that beauty had lost its meaning. There was a kind of reverse Keatsian belief—not that “Beauty is truth, truth beauty,” but the opposite way around. The truth is to be found in ugliness and therefore there was something superficial and frivolous about celebrating the beautiful. I can’t remember who it was who said, “There can be no poetry after Auschwitz.” You cite that person in your essay.

MG: (19:43.869) Theodor Adorno.

II: (19:47.114) I’ve been thinking about that a little bit recently with the pro-Palestine marches. I don’t want to get into that topic. But whichever side of that conflict you’re on, one thing that struck me is that activists have been protesting in places where people are celebrating the beautiful. And the same is true also of movements like Extinction Rebellion, throwing the tomato soup on paintings with the justification that we shouldn’t be enjoying beautiful stuff when there are bad things going on in the world. I find it interesting that Extinction Rebellion in particular and Just Stop Oil and those movements have focused so heavily on art galleries and artworks. I don’t know if you see a parallel there.

MG: (20:49.629) Yes, I definitely see a parallel there.

And I find all that reprehensible. I have a pet theory about what happens, why we went through this sort of humanity-wide existential crisis in the 20th century. I don’t think you can claim that it was absolutely the worst century. There were some unprecedented horrors, but there are also different types of horrors, like, try telling someone who suffered under Genghis Khan that nobody understood horror until the 20th century. There’s plenty that had gone wrong.

But what I think happened is because of modernity, because of this really rapid technological advancement, all of a sudden humanity could solve tame problems at an accelerated rate. A tame problem is a technical problem, a scientific problem, the kind of thing that is like solving a puzzle. And everyone can agree on what the nature of the problem is. And then you just have to ... you can apply the scientific method to figure out a solution to it. But then we have these wicked problems, the social problems, psychological, intractable problems. And as we were solving tame problems at an unprecedented rate, we are not solving wicked problems the same way. So there’s this incongruous experience of why is it that we can accomplish these technological marvels, but we’re also going to slaughter each other and now we can do it at economies of scale. So I think that what psychologically broke a lot of people was trying to wrap their heads around that. So, in the 1930s, we get the invention of the window AC unit and we also get the invention of the gas chamber. What was unprecedented was not that we’re committing atrocities like never before, but now we can do it from the comfort of an air-conditioned room. And that feels particularly obscene. So I think that was what was so unsettling. And I’m sympathetic to how bothersome that is. I remember thinking to myself, it’s like, we can put a man on the moon, but we can’t stop all these horrible wars and genocide and why can’t we have equal rights all over the world? How is it that women are still being treated as objects in some parts of the world? What’s going on? How is this possible? And I think this distinction between tame and wicked problems and understanding that there’s this category of wicked problems that is qualitatively different than any of these tame, more technical scientific problems, once you think about it, it doesn’t make sense to assume, if we can put a man on the moon, we should be able to do this because they’re in totally different realms. So I think that was what bothered people like Adorno, who said that poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric: they just couldn’t handle that incongruity.

II: (24:07.015) Yeah, you cite, in opposition to Adorno’s views, you cite Viktor Frankl in your piece. I’d like to just read that quotation because I think it’s especially powerful. Victor Frankl, of course, was the Holocaust survivor who wrote an amazing book called Man’s Search for Meaning. Here, he’s writing about Auschwitz prisoners being transported. And he says,

As the inner life of the prisoner tended to become more intense, he also experienced the beauty of art and nature as never before. Under their influence he sometimes even forgot his own frightful circumstances. If someone had seen our faces on the journey from Auschwitz to a Bavarian camp as we beheld the mountains of Salzburg with their summits glowing in the sunset, through the little barred windows of the prison carriage, he would never have believed that those faces were the faces of men who had given up all hope of life and liberty. Despite that factor—or maybe because of it—we were carried away by nature’s beauty, which we had missed for so long.

That’s really extraordinary, right?

MG: (25:35.025) It is. It’s hard not to cry every time I read it, even though I’ve read it a million times.

II: (25:45.42) Yeah, so it seems that there is some deep-seated human yearning for beauty and beauty is meaningful. In particular, it’s a meaning that is both experienced on an individual level and created ... well, nature’s beauty is obviously not created by individuals, but artistic beauty is created by individuals, by individual artists and craftspeople and architects. Yet it also feels to the spectator, to the person viewing it, it is something transcendent. And it’s precisely something that takes you outside of the restricted world of the self, something that’s particularly liberating if the life that you are leading at that moment and your personal existence is one of so much suffering as was the case with the people who were the prisoners at Auschwitz. I think that idea of the experience of art being an escape from the individual experience, the personal experience of life into... Sorry, let me re-express that. It’s an escape from... If I’m viewing an artwork, rather than looking directly at the world with my own eyes, I’m allowing somebody else to show me their vision of the world. And so I’m seeing things with fresh eyes, with their eyes. It’s something that is external to the self. And that seems very different from the experience of something like those white blank canvases where the art curator suggests that you are supposed to just look and create the meaning yourself. And also very different from something like the four minutes and 33 seconds of silence, that piece of quote unquote “music,” where the experience instead of experiencing somebody else playing and performing music that was written by another person, you are supposed to listen to the audience and each other. John Cage, that’s the artist who created that. Those seem to me like very different projects. Do you think that’s a fair assessment?

MG: (28:41.171) Yes, I think that I mentioned that perhaps some of this work would have been better off as poetry. I think that a lot of the ideas could be expressed in an interesting way. When Duchamp talks about putting art in service of the mind, well, we already have philosophy that’s in service of the mind. And if there’s a way to make that philosophy really interesting and beautiful as an experience, then I think that’s the job of the artist. But I think that what John Cage did was not going to give anyone the kind of transcendent experience of listening to Bach’s Cello Suite or Billie Holiday sing “Summertime.” And to me, of the three I just mentioned, there’s one that we would obviously not cry over if we were to wake up tomorrow and find that it disappeared from the art canon.

II: (29:43.72) Although I particularly like the bit at 1 minute 9 seconds in.

MG: (29:47.657) Except for that one moment. That one foot shuffle, that suppressed cough was just such a symphony to the ears.

II: (29:59.773) Yeah. I think there’s a strong feeling of snobbery in this, intellectual snobbery, which is not something that I’m necessarily against, but I would say that there is a gatekeeping here that you need to be sophisticated enough to appreciate the art. And returning to my friend’s experience of seeing the white canvases, one of the things that was written on the little card by the side of the canvases, which the curator had written, was this. “One of my favourite things about modern art is the rage that it seems to provoke in some people.” And indeed that sentence provoked a lot of rage in my friend. The suggestion is that you have to be intellectual enough, you have to be educated enough to put the clothes onto the emperor with your own imaginative resources, rather than getting annoyed at seeing the hairy bollocks dangling in the wind. And I think that’s reflected also in the prices that many modern artworks fetch that seem disproportionate to the effort that went into creating them. So if you have a piece like ... who’s that artist who does the corners that are rubbish and things? He puts rubbish and cigarette butts and beer cans as installations.

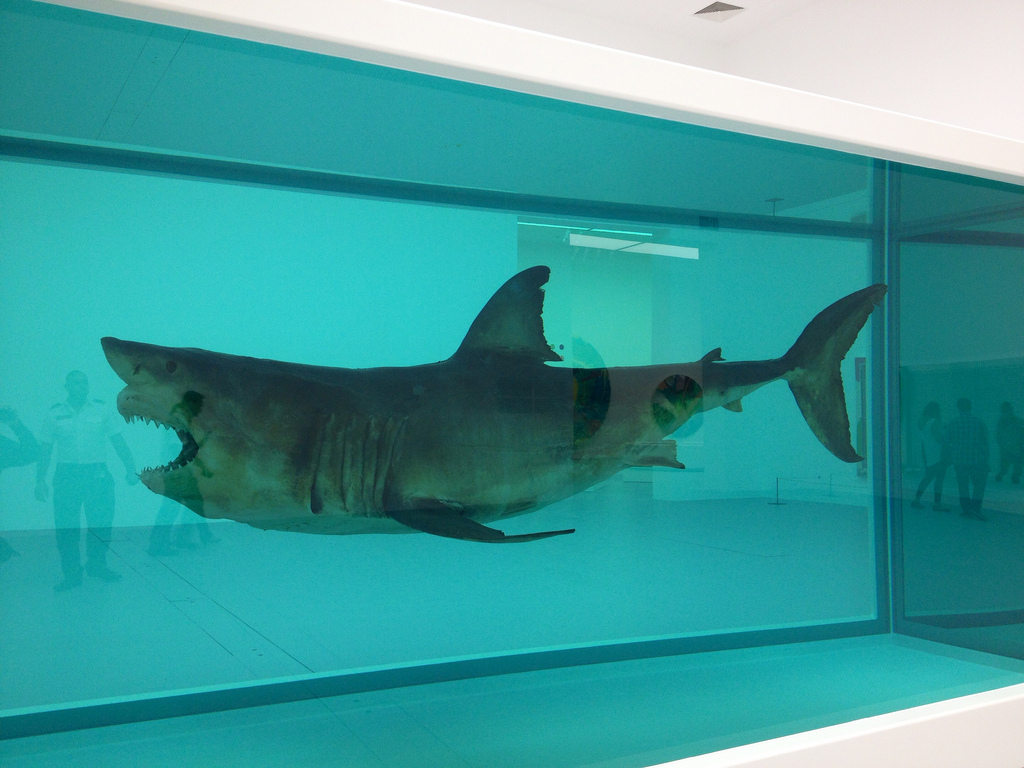

MG: (31:56.873) There have been a few artists who have done things like that. You might be thinking of Damien Hirst. The janitorial staff accidentally threw it away and because they didn’t realise it was supposed to be artwork. There’s another famous one by Tracy Emin. I forget the exact title, but it’s about her dirty bed and she just recreates a super messy bed in the middle of the gallery.

II: (32:24.44) Yes, I’ve seen that one actually. I mean, you just need to have a 15-year-old son. You don’t need to go and see that exhibit. I think there was one called “Fettecke,” [1982, by Joseph Beuys] which is fat corner, fatty, greasy corner and cleaning staff got in lot of trouble because they cleaned it up. They didn’t realise it was an art installation. It was literally a corner full of dirt.

Those are installation pieces, but there are equally many pieces like Duchamp’s urinal that took almost no work to create and that are commanding extraordinary sums of money. On the one hand, that’s high artwork. And on the other hand, there is a lot of absolutely beautiful and exquisite craftsmanship that I see by browsing artists on Instagram or on Pinterest, which I think probably many art critics would despise as being middlebrow.

MG: (33:47.251) It’s become a totally separate field. The art students who have incredible drafting skills, the people who really know how to draw usually go into illustration. I teach drawing at university and I can’t think of a single super talented drawing student who was going down the fine art path. I’m pretty sure they all go into illustration. That’s where the craft of drawing and painting is kept alive and well. And of course, a lot of those are digital nowadays too, but all of my students who can really draw well want to become illustrators. So right now, I think it’s just seen as this totally separate commercial field. It’s not high art. By the way, what you mentioned about the expense of all this artwork, I could be wrong about this, but I think it’s the case that Duchamp was declared the father of contemporary art right after his fountain sold for obscene amounts of money many decades later. I can’t remember. So we’ll have to fact check this, but it might be the case. Once it sold for a lot, that’s when he got the title. Not to say he wasn’t famous in his own time. He was. He emigrated to America. People were already enamoured with him and his career took off.

And then he ... I think it was just a year after presenting his urinal, he left for Buenos Aires and played chess for decades before coming back and making a little more artwork. And I actually want to ask you, because I know that you lived in Buenos Aires and you described yourself as not a great chess player, but I assume someone who loves to play chess, for you to bring it up. And I was wondering...

II: (35:36.438) Yes, I’m an execrable chess player. I love chess, but it’s an unrequited love.

MG: (35:44.297) I was curious if you experienced any of Duchamp’s influence on chess in Buenos Aires.

II: (35:52.933) So, I have read about Duchamp’s influence on chess. I took up chess fairly recently. I didn’t play chess when I was living in Buenos Aires. I hadn’t yet discovered the joys of chess. Yeah, I have read about Duchamp’s pursuit of chess before. Chess does seem to have this ability to seduce people into dedicating their lives to it, even though they are not that good. And it has interesting contrasts with art in that there is an element of luck in chess, of course. Not only that there’s luck in whether you play White or Black, that’s somewhat trivial. What has more of an element of luck is: Does your opponent play things that enable you to play lines that you have learned or to play openings that you favour? Do things happen within the game that are patterns that you’re familiar with or that you understand how to respond to? And that is really largely luck. So I have an opening, for example, that I like to play—the Evans Gambit—and I can only play that opening if I’m playing White and my opponent does certain moves, then I have the opportunity to play that and I’m more likely to win the game because I have some resources there. I still mostly lose, but I have better success with the Evans than otherwise. Setting that aside, there are some elements of luck, but it’s mostly not subjective at all. And not only that, but there’s no argument about whether one chess player is better than another. There is a numerical value set on your chess skill, which is called your Elo. So you can actually measure to the digit how good a chess player or otherwise you are. And that makes it an especially merciless kind of status game.

MG: (38:12.509) Well, a mercilessly objective one. I don’t know anything about chess. I know how all the pieces move. I could play a game and I’m sure you would beat me. I just know the very basic rules of how you can move each piece around. But it’s really interesting to hear because Duchamp was the one who, more than anyone else, removed objectivity from the art world.

And then right after doing that, right after his opening gambit in the art world, which paid off for him, he then went and spent, I think something like 20 years, can’t remember exactly how long, quite a long time doing something so objective. Such a hypocrite.

II: (38:56.79) I think maybe at some level he felt like a fraud. I was reading—I think this was in another piece that you wrote actually, or perhaps it was a piece you cited—about Andy Warhol. As everybody knows, Andy Warhol, the modernist artist whose artworks were often repeated screen prints, etc. I quite like Warhol’s art. Again, there’s not a high level of technical skill and artistry that goes into those pieces. And when Warhol died and the executors took photographs and released photographs of the interiors of his apartment, they found that he didn’t own any modernist artwork. All his art was classical art and sculpture. These traditionally painted figurative pieces, painted with a lot of detail and skill and aesthetics and classical and classically inspired—not actually classical, but classically inspired—sculpture.

And so there was a certain hypocrisy in that, which I find quite interesting. And I was thinking about this also in relation to something that you said in another piece you’ve written, which is about art deco architecture in the US. And I will put a link to that article as well in the show notes. You say that in the past, it was normal for people who were the patrons of art, wealthy people, to have artworks and buildings commissioned that would be temples to, homages to their tastes and appreciation. So they would be richly ornamented and detailed and that was a sign of status. Your status was expressed partly by contributing something beautiful and grand that was either a public building in your name or a private residence, but the beauty and ornamentation was part of the status.

There are some modern examples of this. There’s a building here in Sydney at the University of Technology, UTS, called the Chau Chak Wing building. It’s named after a man called Chau Chak Wing. And it’s a rather lovely modernist building with a lot of ornamental details that are non-functional. For example, the outward walls have a curve, they have a kind of sine curve around rather than simply being straight. I’ll provide an image down below. It’s still not as beautiful to me as older buildings, but it does have this, it’s more original, more interesting visually. But in general, there seems to have been a disconnect between those kinds of status games which actually had led to an enrichment of the visual environment for everyone and the status games that are played with modern art and modern architecture.

MG: (42:53.789) Yes, it went from visual taste to your ideological taste. And not always political, often it’s just a kind of philosophical theory that is pretty incomprehensible to the uninitiated. And so the status game is about understanding the jargon, understanding what the theory is telling you, you should think about all this artwork and... I’m with you. I’m not totally against snobbery. I think that there are things that are just objectively more beautiful than others. And I will be a snob and stand by the things that I think are more beautiful. And I’ll try to make a case for that. And I think the big difference is there’s this kind of obfuscating, this loss of clarity that you get once you get deep into the postmodern theorists where most people don’t really understand what they’re talking about. And then the status does very much become: Can you hold your own in a conversation when you’re talking about these ideas?

II: (44:10.764) Yeah, absolutely. The status is I’m intellectual enough to understand this thing that seems either pointless to other people or ugly or incomprehensible gobbledygook. And when I was an academic myself, it took me a while to get past that. For a long time, I just felt a sense of intellectual inadequacy. I at least never pretended to understand the stuff. I just thought, I better not talk about or mention any of this stuff because clearly there are some ... everyone else is much cleverer than me and they are able to get it and I don’t get it. And now I just feel, No, this stuff has always been bullshit.

MG: (44:53.285) Yeah. You know, Judith Butler is such an easy target, but I’m going to pick on her anyway. She’s famous for her incomprehensible sentences. And I am sceptical if anyone really thinks that they understand what she’s saying. She’ll throw in a comprehensible sentence every now and then they can latch onto. But yeah, I definitely think that it is... It’s like you said, the emperor has no clothes kind of situation except there’s this defence mechanism now where if you try to point out, hey, no clothes, guys, walking around naked, then everyone laughs at you. And instead of turning to me like, yeah, he is, laugh at him, they’re like, you just don’t see the clothes.

II: (45:40.688) Yeah, I mean ... this extraordinary idea of the curator of that Queensland Museum—sorry to keep picking on this poor woman—that part of the reason for artists is to enrage, part of the joy is to enrage people who feel pissed off because they don’t understand what’s going on. That’s a very, I feel, snobbish attitude, snobbish in a really negative way, insulting.

MG: (46:13.617) It’s like snobbery for the sake of snobbery instead of snobbery because I just really genuinely prefer this painting or that music and I don’t want to ... I’m going to listen to Bach not Taylor Swift kind of attitude. Within that, if you’re snobbish about music, then usually you have an evangelical side to your snobbery where you want to convince people and you want to share this with them and you want them to enjoy it with you and to take part in your snobbery. Whereas the kind of snobbery you’re describing that this curator has is revelling in putting so much distance between the normal philistines who don’t get it and us so sophisticated people in the art world.

II: (47:02.664) Yeah, yeah. I think that people who are public intellectuals could actually do a service by debunking this stuff by saying, look ... I clearly am intelligent, even though that sounds very narcissistic and vain to say, but I think people could ... do a service by saying, look, my intellectual credentials are, are pretty clear. I can tell you it’s not that you don’t understand this stuff, it’s that there is nothing to understand here.

MG: (47:38.823) Yeah. I really love the way Steven Pinker talks about good writing as something that makes the reader feel like a genius. That when someone communicates something clearly, it gives you that feeling of an epiphany. Hoffer talks about this as well. I think the way he puts it is it feels as though the idea originates inside yourself. Again, you as a reader feel like a genius, even though you’re not the one who wrote this or came up with it, but the clarity and having those pieces just click into place is what is, I think, the valuable philosophising or art-making that we ought to be doing, the valuable writing we ought to be doing. And instead, what a lot of the contemporary art world and a lot of this Judith Butler-style academia writing does is I think they try to make people feel stupid. So again, the good snob tries to make you feel like a good snob too and to bring you closer and try to open your eyes to something that you think is so much more beautiful and you’re missing out. The bad type of snob just is going to leave you there, like a bully, is going to leave you there feeling dumb.

II: How do you think that AI is affecting the art world and how people are perceiving art? I’ve noticed a vertiginously fast improvement with the various versions of Midjourney and Leonardo and the other AI art programs that are out there.

How do you feel about that and how is that affecting and changing the game, if you think it is?

MG: (49:39.899) It’s probably too soon to fully tell. I think the people who are most in trouble are going to be more commercial artists. You’re not going to need to hire as many illustrators for ... not the kind of things that we think of as high art, but the sort of day-to-day day jobs that a lot of artists could get that would then support them making their own kind of art. That might be one of the biggest blows to artists. The graphic designers are going to get hit harder. One thing I’ve thought about is, it’s like how after the invention of photography for a while, people said that painting was dead and painting has lately been the most lucrative kind of artwork you can make. And I think that at a certain point, photography became ... we became so saturated in photographs and photography became so much easier, especially nowadays. You don’t have to have much skill to take a nice photograph.

And so photography had its moment, but especially as it became more accessible, similar to this AI trajectory, then the traditional art form of painting actually had a resurgence. And so we might see something like that where the traditional handcrafted arts develop another resurgence because of AI.

I’m more of a techno-optimist myself. I love science and technology and I would never discount how much it would suck for someone to lose their day job and how is this artist going to now cultivate their skills and not be spending ... if your day job is also artistic, you can cultivate your skills at the same time and that’s a big benefit versus now having to support themselves in a totally different way and they have to spend all this time learning multiple skill sets in order to thrive.

So there definitely would be some downsides, but I’m not sure it’s going to upend the kind of art that we think of as like a Dostoevsky novel. I don’t see AI writing anytime soon. I don’t see AI being able to produce something like a Van Gogh painting. I mean, who knows? Maybe we can hook up the Journey to a CNC machine and see what it can put out at some point or a 3D printer.

I think if anything, it’ll just make us appreciate the traditional arts more if it follows in the footsteps of photography’s revolution.

Really quick, something you mentioned a moment ago that I wanted to respond to when you’re talking about this disconnect of how much some of this artwork costs versus the effort that was put into it. Something right now that’s really interesting is there’s been a market crash in the art world recently where a lot of young artists in particular who are plucked out from the herd and are going to be the next big thing and their artwork is selling for many tens of thousands of dollars. Their work is now going to auction and its resale price is plummeting, losing something like 80 percent of its value. It’s insane. So the art market’s floundering right now. And I’m not privy to the causes of that well enough to explain it, other than to note that there is maybe a speculative quality to the prices of a lot of this work, especially newer work. Duchamp’s urinal, unfortunately, is probably always going to be worth a lot of money. Unless I get my way and we all think he’s stupid. But it’s hard right now for younger artists, artists my age who don’t have that longstanding prestige. And I think a lot of that has to do with this.

Again, I don’t understand all of the economics going into what’s happening right now, but I can’t help but suspect that the fact that artists are not expected to have the kind of skill that is undeniable, like, we’re talking about pretension. Duchamp really invented the pretentious artist. It used to be that you could look at the skill and it justified itself. So you could have artists with any range of personality types, but if they could perform, if they could make the incredible painting, they could compose the symphony, then that stood for itself. But now it’s very much people convincing themselves of this or that movement is what’s important and there’s not this objective standard. So without that, it can become very speculative is my guess.

II: (54:25.073) Yeah ... some of the prices must be based on what you think the resale value will be, etc., rather than something specific, as you say, to the work itself. It’s more about pure money markets and finance. I’m fairly hopeful about AI. One thing that I’ve noticed is that people still really love hyper -realist drawing. I have a friend who makes money as an artist and she draws from photographs and her drawings look ... her aim is to make her drawing look as much like the photograph as possible. And you would think this is completely superfluous. You could just take the photo, but the fact that you know that she drew them rather than them being a photograph and the fact that she is able with manual skill to reproduce the photographic effect so closely, that in itself people find extremely charming, including me—I bought one of her pieces as a gift for a friend.

And I noticed that we see that going back to chess as well. AI can play chess much better than we can, but people are on the whole, they’re using AI as a tool to improve their own chess, but they’re not really interested in watching the AI play chess. We still want to watch humans play chess, even though AI surpassed us back in the 90s.

MG: (56:09.091) It’s about pushing the limits of what humanity can accomplish. so when it’s an athlete, you watch somebody who can ... you watch Usain Bolt run faster than anyone in the world. And you marvel at the accomplishment of that. And you see Michelangelo carving the Pietà and you marvel at his ability to make this hard stone look like undulating fabric and to capture the grief on Mary’s face. Showcasing the extreme limits of human accomplishment is something that most people cherish. When someone is such a keen observer that they can replicate that photograph and you’re just like, My God, how can you put together all these little marks! That blows people’s minds. so yeah, I think hyper realism will probably always be really popular.

I know a very successful hyper realist painter, who’ll go unnamed and this person has painted some of the most famous people you can imagine. And I got into an argument because I said, “I just saw your portrait of so and so at the National Portrait Gallery in DC.” And he’s like, “No, no, it’s not a portrait.” And then we get to this long argument where he’s trying to justify to me. I mean, he’s a very important artist. He doesn’t have to justify himself to me, but he’s entertaining my arguments. He is just ... he’s very adamant these are not portraits—but these are very hyper realistic, super famous people that everyone would recognise. You can’t even make an argument that because it’s anonymous, it’s not a portrait. I’ve always thought that maybe that was necessary for him to convince himself of that to become such a successful artist. And I was an asshole, like, “No, no, no, you don’t understand your own art. You’re definitely making portraits.”

And so it was a good-natured argument, but you do see that kind of thing where people, artists tried to smuggle beauty or skill or something back in, but they have to do this convoluted justification for it. And usually you can use the justification of a political art, but there’s also these more theoretical justifications like this artist was making. I wish I could remember his specific argument better, but it was a little incomprehensible to me. I was just like, How can you tell me not to believe my lying eyes that these are portraits?

II: (59:07.169) Yeah, that seems to sum up a lot of modern art, which is trying to convince me not to believe my lying eyes—that this isn’t just white paint daubed onto a canvas, returning to that example. There’s obviously more obvious reasons why political art tends to be bad. Art is about the individual vision rather than copying the orthodoxies of a mass movement. I think we don’t really need to get into that because that’s probably obvious to listeners.

But one thing that I find quite interesting is the reasons why we have ... why, for example, modern architecture is often so ugly and so boring, that we’ll see a building into which billions of pounds have been invested or dollars, and it will be a blank concrete box with really no charm, no detail, no ornamentation. It seems to me like a tragedy of the commons has happened here. How have we got to this stage? How have we got from an age like, for example, the early art deco age in the United States, those beautiful early skyscrapers in, for example, New York and Chicago, in which the beauty of the building was part of the point, to this extreme devaluing of beauty in the public sphere.

MG: (01:01:10.899) Yeah, so there’s, in architecture specifically, a very popular assumption that it’s too expensive to do all that ornamentation. This caught on after World War II when times were tight for sure. But it is in fact not true that ornamentation is just so obscenely expensive that the wealthy—the people today who are wealthier than people have ever been in all of human history—couldn’t have it if they wanted it. It’s definitely a choice. There’s this almost mind blowing essay by Samuel Hughes. He’s a research fellow at Oxford who studies architecture. This came out a couple months ago. I can send you the link for the show notes if you’d like. And he breaks this down and very thoroughly and he goes into the history of our ability to cast and carve this kind of ornamentation you see on buildings and how well we were able to mass produce it before modernity, which there was some ability to do. But then how, once we have things like trains that can haul massive amounts of material and all these other innovations, now all of sudden the ability to mass produce ornamentation became so much more affordable and feasible.

This was the era of those Art Deco skyscrapers and these tycoons of industry like Walter Chrysler who commissioned the Chrysler building, which is my favourite Art Deco skyscraper. He said he was making a monument to himself and he wanted all this ornamentation. And with a skyscraper, the building is so huge that you have economies of scale and you can do this bespoke ornamentation with those economies of scale. If you have regular people who want ornamentation, they’re going to not have it be as bespoke that you would for these chrome eagles that you’re only ever going to see on the Chrysler building. They’re not going to have that kind of originality, but they’ll have a lot of decorative elements. And we do still see a lot more decorative elements on suburban homes than you would in Bill Gates’s flat. One of the things that Hughes points out again [is] you can believe your lying eyes, if the ornamentation was so expensive, then why is it that the one place it’s still clinging on is with the non-elites or the less elite you are, the more you’re allowed to enjoy ornamentation but the ultra-rich they all have these very sleek-contemporary looking apartments. Maybe not all, that’s probably too much of a generalisation. I hope not. But in his essay, I think I recall he had an image of Bill Gates’s flat. if you’re Bill Gates, you could afford to build a Chrysler building style monument to yourself if you wanted to. But that isn’t what is desired anymore.

And I really liked the way that Hughes puts it, where he says, the nice thing about believing that this was an economic problem is we don’t have to accept the fact that we chose this, that this was a cultural choice. We could have chosen otherwise and we still could. And we now have the technology to mass produce ornamentation more affordably than ever before. And that doesn’t mean that it might not be more expensive to have ornamentation than not, but that it’s certainly not prohibitively expensive. And it’s about values. Where are you going to put that money? And as you pointed out, people spend a lot of money on this modern architecture that most people hate. My favourite commentator on this was the very witty Tom Wolfe, who died relatively recently, maybe half a dozen years ago. And in his book, From Bauhaus to Our House, he talks about how it was these German socialists and the Bauhaus who immigrated to America because the Nazis were persecuting them. And then there’s also like [Willem] Bossier, who was Swiss born, but spent most of his life in Paris, I think. He was not as ideological as these German socialists from the Bauhaus, but he was still very obsessed with all these clean lines and removing ornamentation.

And in their case, in the case of architecture, they had these very left-wing views about trying to make architecture more what they saw as egalitarian. They talked about it, they called it worker housing. And they never asked the workers what they wanted. There’s some really funny instances of the workers who’ve been subjected to this demanding that this all be torn down and burned down. But it was this ideological movement, it was the power of ideas. It wasn’t this post hoc justification downstream of economics. It was an idea and the economics followed. A lot of those decorative firms did go out of business. I’m sure ornamentation is a lot more expensive now than it would be if we had never disowned it, if we had for the past century this industry of ornamentation, like we did in the Art Deco period, I’m sure it would be more affordable now in that counterfactual. But it would certainly be possible to have the ornamentation. It wouldn’t break the bank. It’s a choice. It’s about what we would consider to be sophisticated. I suppose that the ornamentation just seems too pastiche.

My favourite example of a very new skyscraper is in Brooklyn. It’s called Brooklyn Tower. It’s the tallest skyscraper in Brooklyn and it was finished a couple of years ago. And it bears ... it’s called Neo Art Deco, which is really interesting to me because I love Art Deco and I see what they mean by that in some of the design, but it looks just like Sauron’s tower from The Lord of the Rings movies. It’s a spitting image. So that has become its nickname. So now we have the Eye of Sauron menacing downtown Brooklyn. And this was one of our new celebrated skyscrapers. It is like this onyx black glass building. It’s certainly more accessible nowadays to have decorative architecture than it was back when Walter Gropius and Le Corbusier and all of these modernist architects were really ascendant. So you see a little bit of ornamentation on this where I can kind of see what they’re going for with Art Deco. But for the most part, it is another tall glass rectangle that has this Eye of Sauron crown at the top. There’s some really funny quotes. I was reading the New York Post about this skyscraper when it came out where people were saying, You know, I would rather look at something evil than just another boring box. And so my Art Deco essay talked about how this is what a century of modern architecture has done to us. We are relieved to find ourselves in Mordor instead of the Bauhaus.

II: Here in Sydney, there’s a similar example. The downtown line of skyscrapers form the classic—well it’s not classic—the Sydney skyline. There is one skyscraper, it’s shaped a little bit like a tulip bulb. It’s just a tiny bit different in shape from the others, which are all just long upright concrete rectangles. Everyone loves it and it does look like a phallus and it was designed by or think maybe paid for by a businessman called Kerry Packer and it’s known as Packer’s Pecker. And yeah, people feel quite affectionately about it even though it’s just ...

MG: (01:09:29.171) And does everyone love it because at least it breaks up the monotony?

II: It’s no more sophisticated than a drawing of a penis and testicles on a toilet wall, right? But it’s a little bit different from the others and therefore people have affection for it. We’re just yearning for something that has some individuality, some touch of something.

MG: Yeah, and speaking of drawing, another pet theory of mine is that ... so a lot of these early modern architects who are so famous, like Le Corbusier is so famous in the world of architecture, but they produced almost no buildings themselves. I’m not sure if it’s true that you can count on one hand how many buildings Le Corbusier had built, but it wouldn’t be far off from the mark. So, it got to a point where within the world of architecture, people were joking about how we used to give awards for building buildings and now we give awards for making drawings of them. Because so many of these architects are largely famous for their drawings of hypothetical buildings. My pet theory is that a lot of this architecture does look beautiful in a drawing, where those clean lines and smooth gradients can be very attractive. I love looking at diagrams and the kind of things that draughtsmen would make as a schematic. There’s to me something beautiful about that. I think that people ... ironically, because so much of what these architects wanted to do in removing ornamentation was part of this 20th-century disavowal of beauty. And yet I think they were attracted to the beauty of these drawings. And then, after falling in love with them, they just kept trying to make the building mean as much to them as the drawings did. I can’t remember which architect this was, but I recall reading a funny quote of one of the architects who had to keep making glass boxes and people would be like, You keep making the same thing. He’s like, Yes, and I’m going to keep doing it until I make one that I like.

And I remember reading that and thinking, it’s because the drawings look so much better. Once you build the thing, it almost always looks like it needs to be pressure washed. The old buildings, buildings that are centuries old, they don’t have to be pressure washed constantly. That patina of time makes them look even more beautiful. It gives them this richness to the texture of the building that you don’t get with modern architecture. And I think that there’s something really interesting about how ... There’s this really great line from an American poet, which says, “Beauty, old yet ever new.” There’s something about beauty that ages like a fine wine, but you’re not going to have that experience with modern architecture.

II: (01:12:55.288) I feel that there might be some more profound puritanical impulse there as well. I was reading recently an article about the Patrick O’Brian historical novels, which if you’re not familiar with them, it’s a series of seafaring tales. There are 20 novels and they are set in the Napoleonic period.

And very unusually, they contain a very, very high degree of old-fashioned craftsmanship in that they are written in the prose of that period. They’re modern historical novels, but they’re written absolutely consistently in the prose of Jane Austen or of Jane Austen’s time and with an extraordinary and meticulous wealth of historical detail. I studied and taught that period when I was an academic. Actually, my speciality period was a little bit before that, more early- to mid-18th century, but I also taught the late-18th-century period. So I can vouch for the authenticity. I haven’t spotted a single jarring thing. And this is over 20 novels.

MG: (01:14:19.881) Impressive.

II: (01:14:22.22) The article was talking about them, decrying them for being middlebrow, as opposed to some more highbrow novels that are just less popular. And the middlebrow accusations seem to be largely based on the fact that people enjoy them. I think that there is a perception that if there is a lot of enjoyment and pleasure to be had, if a lot of people are taking a lot of pleasure in a work of art, it must be not that sophisticated, that there is a zero sum equation between pleasure and meaning.

MG: (01:15:06.237) Yeah, they want you to have to struggle and work for it.

II: (01:15:09.396) Yeah, yeah, exactly. Popularity is an adverse marker signal to them. It’s popular, therefore bad also.

MG: (01:15:14.884) Yep, it’s in the art world, it’s its own little microcosm. It’s a kind of insular community. It very much talks to itself. And that’s why so much artwork becomes self-referential, where artists are referencing this artist and that artist from decades past. And when you have a field that is talking to itself too much, then they definitely maybe lose touch with these important facets of human nature, this craving for beauty. It would be really interesting to see how many more people like Andy Warhol had a secret cache of classical artwork.

II: (01:16:09.98) Yeah, a guilty secret. The postmodernists ... one of the one of the things about them is this obsession with language, this kind of magical thinking belief that by changing language, you can change the world, or that there is no there there; it’s all just descriptions and representations. If you are obsessed with things that can be expressed in language or played with using language, that is orthogonal to the enterprise of visual arts.

MG: (01:16:55.761) Yeah, it’s all very didactic. It is, I think, in a lot of ways, more in the realm of philosophy than art. Philosophy is very interesting. I love learning about philosophy, but it’s confusing the purpose. I sincerely believe that the purpose of art is to be looked at. And beauty is for us artists our very ancient raison d’être. I am very interested in philosophy but it’s just not what I am. I am not a philosopher.

I would like to end on the point I ended my Quillette essay on. Because this, this to me really captures the reason why I feel like Duchamp really destroyed art to a degree, which is a quote from Victor Frankel. Frankl believed in, and I quote, “loving dedication to the beautiful.” And he said,

Should I perhaps try to explain for you with some hackneyed phrase how and why experiencing beauty can make life meaningful? I prefer to confine myself to the following thought experiment: imagine that you are sitting in a concert hall and listening to your favorite symphony, and your favorite bars of the symphony resound in your ears, and you are so moved by the music that it sends shivers down your spine; and now imagine that it would be possible (something that is psychologically so impossible) for someone to ask you in this moment whether your life has meaning. I believe you would agree with me if I declared that in this case you would only be able to give one answer, and it would go something like: “It would have been worth it to have lived for this moment alone!”

To hear a Holocaust survivor talk about that, when he says life would have been worth living for this moment, he’s talking about having barely survived some of the worst torture anyone has inflicted on a human being. So, I end my essay by asking people to consider this thought experience from the other perspective: instead of being the person in the audience, imagine that you’re the artist. [tearful] Sorry, I get torn up thinking about Viktor Frankl

II: (01:19:46.868) Yeah, me too.

MG: (01:19:50.229) Imagine that you’re that composer and you can summon enough beauty to make someone want life, even a life like Viktor Frankl’s, the deeply tragic life, because it would have been worth it to have lived for this moment alone. When we absorb the magnitude of Frankl’s exclamation that the torture and humiliation of Auschwitz was worth it just to hear your music, consider it from that perspective and then imagine how if we followed Duchamp and the postmodern artists who reject beauty and meaning and art, then we rob a Holocaust survivor of a reason to live, an artist the honour of creating something worth living for. I get emotional about it because the Holocaust is emotional, but also because this destroyed art, the thing I’ve devoted my life to. And not entirely destroyed—I worry I’m overusing that word because of course there are still people making beautiful art—but it has done so much irreparable harm to art and it’s very deeply upsetting to me. My goal in writing this essay and the reason that Hoffer gave me that feeling when I’m reading his book, they talked about how you feel like a genius reading it where it gives you that sense of epiphany. Let’s realize, wow, this is what Duchamp did to the way that I find meaning in the world within art.

I hope that we can turn the tides, that we can sneer back at Duchamp and say no. If the 90s wasn’t the decade of beauty, then maybe the 2020s, the 2030s, you know, a full century after Art Deco died and the modernists took over, maybe we can come to our senses.

II: (01:21:36.714) I hope so. Megan, thank you so much for joining me.

MG: (01:21:40.699) My pleasure, thank you so much for having me.