Space

The Case for Life on Mars

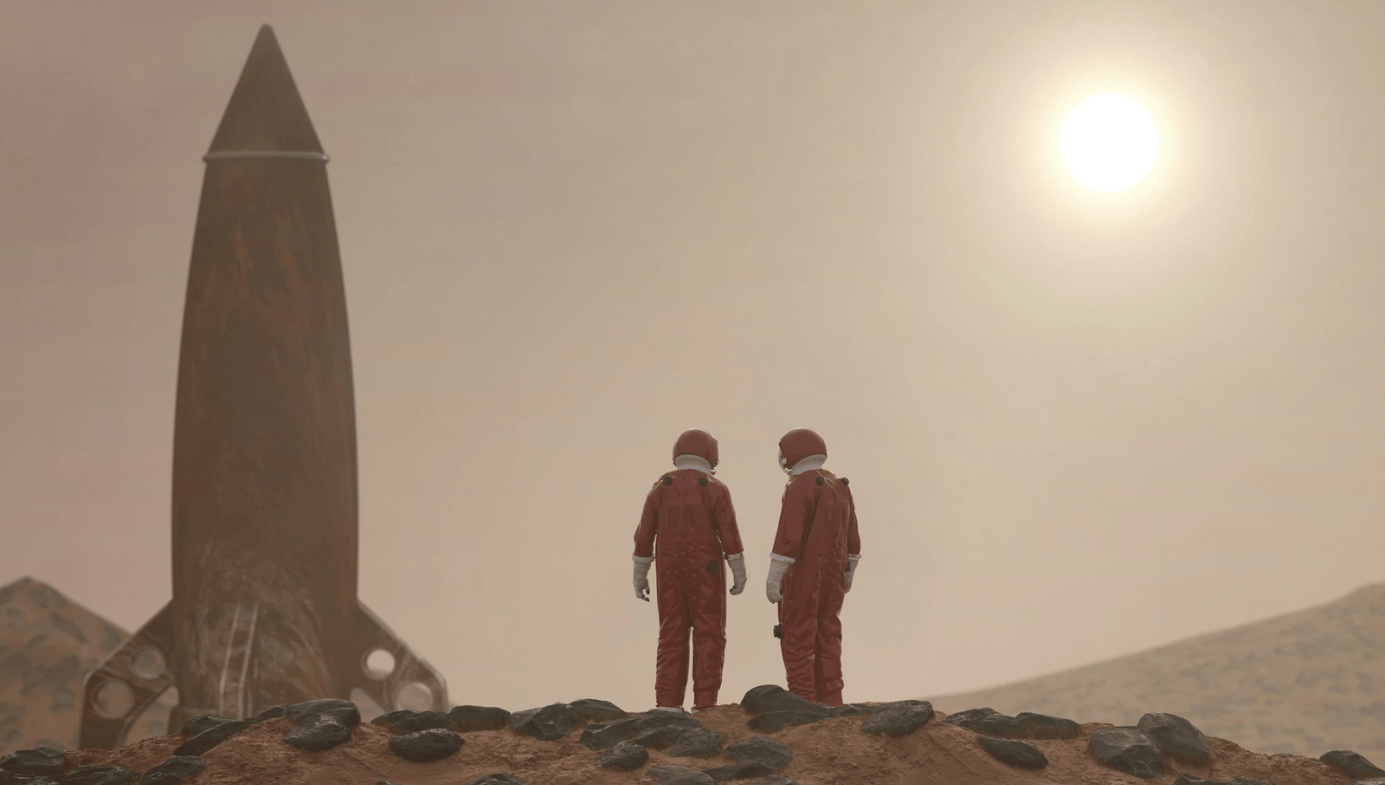

Settling Mars isn’t just about making humanity a multi-planetary species. It is about improving life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness for everyone on Earth.

A review of The New World on Mars: What We Can Create on the Red Planet and Why We Must by Robert Zubrin, 280 pages, Diversion Books (May 2024).

Robert Zubrin’s The New World on Mars: What We Can Create on the Red Planet (2024) is a remarkable book. It’s notionally about colonising Mars and contains plenty of maths, and many diagrams and technical disquisitions outlining how that will be accomplished. But it’s mostly a book about mankind—our history, our capabilities, and our future potential.

Zubrin is well known in space circles. An earlier book, The Case for Mars (1996), is based on his work on Mars settlement dating back to the late 1980s. He has been one of the earliest and most prominent proponents of a “Mars Direct” architecture, which would involve drastically reducing the cost of a Mars mission by extracting propellant from the Martian atmosphere and building shelters out of Martian rock and regolith. In his latest book, Zubrin has consolidated three decades of additional research with substantial new discoveries about Mars made by 21st-century orbiters, landers, and rovers.

Zubrin starts from a position of manifest destiny: we should send humans to Mars, he writes, in quantities sufficient to establish multiple 10,000-person cities, in order to take the next step in human development:

There are likely to be many noble experiments on Mars. Some will fail, but others will succeed, leading their cities to grow, prosper, invent, create, and, by example, set a new standard for the further progress of humanity everywhere.

This is not a universally held belief. Many people argue that we have enough problems here at home, and shouldn’t be expending time and treasure on exploring or settling Mars. Some even argue that we shouldn’t interfere with Mars at all—that it’s better to leave other planets in pristine desolation, lest we export our pollution, factionalism, and wars to other worlds. Zubrin rejects these positions: “To claim that humans do not have the right to alter Mars because Mars has the right to be unaltered is as nutty as claiming that Michelangelo was committing criminal mutilation of marble blocks by chiseling them into statues.” He also contends that permanent Martian settlements will benefit all mankind—even those individuals who never set foot outside our home planet. But even among space enthusiasts, the settlement of Mars is not universally accepted as a goal. Since Apollo, US space policy has been roughly divided into three camps: O’Neillians, von Braunians, and Saganites. Zubrin is marking out a fourth way.

In Gerard K. O’Neill’s vision, humanity should expand beyond Earth, but in large self-sufficient habitats called “space colonies,” orbiting in free space. Exploitation of solar system resources would provide a profit motive, making the colonies an attractive proposition for private sector aerospace technology companies. Although most O’Neillians support the idea of mining the Moon for resources, they tend to be more focused on asteroids and comets. Their attitude towards Mars can be summed up by space venture capitalist Michael Mealling: “Why would I go to so much effort climbing out of Earth’s gravity well, just to climb down another one on Mars?” There’s a strong O’Neillian camp in space development today, most notably led by Jeff Bezos and his aerospace company, Blue Origin.

Others see space as a continuation of politics by other means. Following Wernher von Braun, they believe that spectacular space missions are a way of demonstrating national superiority, much as Apollo showed the world how a free market could outperform the Soviet centrally planned economy. (Ironically, in the process, Apollo created an American centrally planned economy, which set space development back for forty years. We should not have a national “space program,” any more than we had an “aviation program” or an “automobile program.”) Traditional aerospace and defence primes like Boeing and Lockheed Martin fall into this category. They’d be happy with “flags and footprints” missions that have no lasting economic impact, as long as the American taxpayers are willing to foot the bill.

Yet a third group of space enthusiasts, honouring the vision of Carl Sagan and others, believe in sending robotic probes everywhere in the solar system (and perhaps beyond), but not people. This faction believes that the cost and risk of human missions are too high, and that we can collect ample scientific knowledge without risking the lives of human explorers. This camp is best epitomised by the Planetary Society and its fellow travellers. They point with pride to the amazing discoveries of the NASA Mars rovers (Spirit, Opportunity, and Perseverance.) They fail to note that these same discoveries could have been made in an afternoon by one geologist, on foot, with a rock hammer and a magnifying glass.

I suspect Zubrin would reject the Saganites and the von Braunians outright. He would probably make common cause with the O’Neillians, and I suspect would welcome the chance to let the free market thrash out the comparative advantages and disadvantages of Mars cities versus orbiting habitats. But Zubrin and Elon Musk are the leading exponents of a fourth camp, which I will call the “New Martians.” And a substantial portion of the vision outlined in Zubrin’s new book relies upon SpaceX’s Starship architecture for transportation to Mars, upon Mars, and beyond Mars.

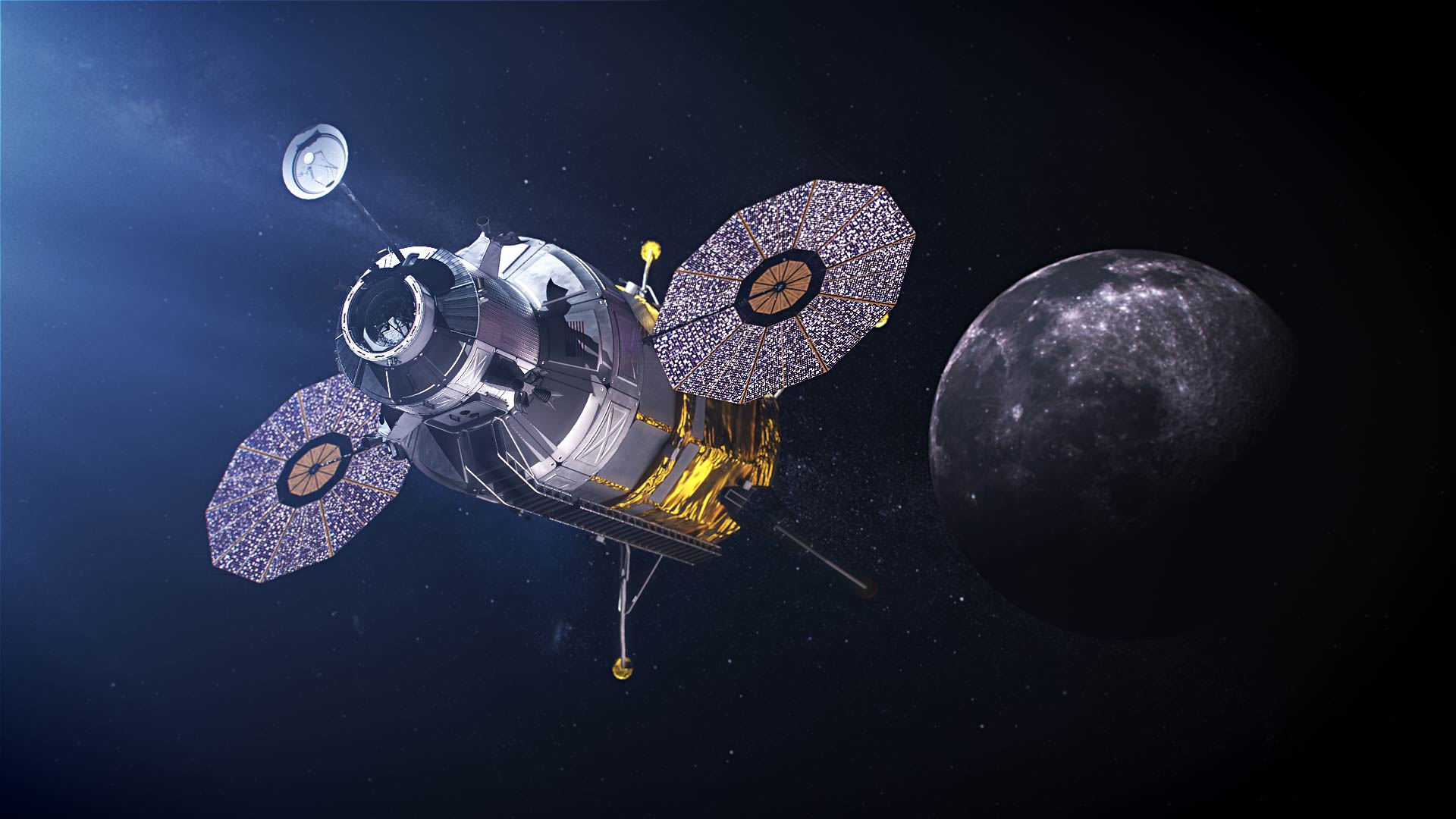

Starship is revolutionary. NASA’s space shuttle, albeit a technological triumph, never lived up to its economic objectives. Each launch cost approximately $1 billion. Once operational, Starship will cost $5 million per flight for five times the payload—an overall thousandfold improvement in cost per kilogramme to orbit. And since Musk is already setting the groundwork for mass production, a fleet of Starships will have the capability to take millions of tonnes of cargo—and thousands of settlers—to Mars.

Zubrin’s book contains a lot of mathematics, which the less technical reader can easily skip. But even if you don’t know the difference between Delta-V and Delta House, the numbers are compelling. The fare for a one-way trip for one person and his or her basic equipment will be about US$300,000—not a trivial amount, but well within the ability of millions of people to liquidate and/or borrow. And, as Zubrin points out, in constant dollars, this is comparable to the price of a berth on a ship from Europe to the New World in the 17th century. People found a way to fill those berths. They’ll find a way to fill the berths on a Mars colonial transport.

In Zubrin’s vision, which he shares with Elon Musk, these will not be “NASA missions” (although NASA may purchase tickets for some of its personnel). In the words of aerospace engineer Rand Simberg, “It’s not NASA’s job to send a man to Mars. It’s NASA’s job to make it possible for the National Geographic Society to send people to Mars.” In the future, “people” could include large companies, entrepreneurial startups, space agencies from smaller nations, church groups—SpaceX and its eventual competitors will carry anyone who can pay the fare. This enforces a completely different set of requirements, metrics, and success criteria on a Zubrinesque Mars settlement.

And the key word is “settlement.” NASA is currently planning for the Artemis missions to return to the Moon. (NASA has no official plans for Mars missions at this time.) Even though the claim is “this time to stay,” the plans for long-term habitation of the Moon are timid, with astronauts confined to landers and, eventually, surface habitats scarcely bigger than landers. The overall impression is of Antarctic outposts, crewed by handfuls of stalwart astronauts with decades of training. Zubrin is proposing cities on Mars: tens of thousands of people with all the living quarters, industrial areas, and life support necessary to thrive in an environment vastly harsher than Antarctica. And to have children there—lots and lots of children. No matter what Elton John sang, Mars will be the kind of place to raise your kids.

Zubrin draws an analogy between Mars and the English and French settlements of the New World. England sent families, or women who wanted to raise families. France built trading outposts, staffed entirely by men. By the 1750s, even though France’s population was four times the size of England’s, English colonists outnumbered the French by 40:1 (2 million to 50,000). Zubrin expects a similar dynamic on Mars. The cities that attract and support the most families will economically win out against technocratic settlements that see children as a bother. Mars needs women—and children—if it is to thrive.

Zubrin runs us through the calculations that demonstrate that lifting all the infrastructure needed to support thousands of people on Mars from Earth is economically unattractive. Only those devices that require a deep industrial base will be shipped from Earth. To use an analogy from the American frontier, you didn’t ship lumber to San Francisco. You shipped axes and saw blades, which were used to cut down local trees and make them into lumber. Whatever can be made on Mars will be made on Mars—from building materials, to homegrown crops, to industrial machinery. Mars settlements will resemble busy workshops and factories more than scientific outposts. The New Martians are going to be busy surviving and thriving. They’ll deliver plenty of scientific discoveries—but they will be discoveries driven by the need to build infrastructure for themselves and their children.

Chronic labour shortages will affect social norms. Children will get much of their education on the job, helping their parents. And elders who, on Earth, would be retired will continue working as long as they are able, passing on knowledge to younger generations. It will be a much harsher world. Zubrin compares the new world on Mars to the New World of the Americas in the 18th and 19th centuries. A shared sense of culture and desire to build a shared future will be critical to avoid social breakdown.

As noted above, Zubrin expects there to be many “noble experiments” on Mars—not a single planetary-wide government, but a messy patchwork of cities, smaller settlements, industrial parks, and possibly individual homesteaders. While not promoting a laissez faire lack of regulation, he clearly believes that competition fosters creativity, innovation, and efficiencies that centralised planning would hamper. It will be interesting to see how this plays out if New Martian cities populated from Western democracies are sharing the planet with more authoritarian outposts from China.

Note that, at this point, Zubrin departs from his fellow New Martian, Elon Musk. Musk has repeatedly stated that he wants to build a million-person Mars city within the next ten years. Zubrin dismisses this goal as impossible. He believes it would be far more feasible to settle multiple 50,000-person cities over the next fifty years. This would also have the advantage of allowing each one to compete with the others for raw materials, people, and capital investment.

But what are all these people going to do? Government-funded settlements will look like Antarctic outposts: small, cramped, and completely dependent on Earth for survival. Fulfilling the vision of true cities on Mars will require unlocking vast sums of private investment capital. What does Mars have that’s worth investment by private-sector entities that want to make a profit? Mars has rocks. Earth has rocks. Mars has (frozen) water. Earth has water. Mars has carbon dioxide. Earth has, arguably, too much carbon dioxide. It’s hard to imagine any scenario in which extracting raw materials from the Martian surface for export to Earth makes any sort of economic sense.

Instead, those raw materials need to be transformed into usable resources. Zubrin makes a case reminiscent of that of David Deutsch in The Beginning of Infinity. He writes that:

There are really no such things as ‘natural resources.’ There are only natural raw materials. It is human creativity that transforms raw materials through technological innovations. On Earth, land was not a resource until people invented agriculture. Oil was not a resource until people invented petroleum drilling and refining and machines that could run on the products. Aluminum was not a resource until the late nineteenth century, when technologies were invented to extract the metal from aluminum oxide. Until then, it was just dirt.

Mars has an entire planet full of raw materials and acts as a gateway to even larger stockpiles in the asteroid belt. Those raw materials will be transformed into useful resources by human ingenuity. And those resources will be used to solve problems, both for the New Martians and for humans everywhere.

The New Martians are going to invent. Zubrin goes through an entire panoply of sectors—from fusion power to biotechnology to industrial automation to robotics—in which focused teams with a compelling need could make substantial advances, especially when liberated from the stultifying bureaucracies back home. Mars will be perennially short of power and labour for decades. Inventions to make more power available and to leverage that so that larger enterprises can be managed by fewer people will be critical to the survival and growth of New Martian cities. But those inventions will be equally applicable to problems on Earth. So the first exports from Mars will not be metals or volatile gases or Martian-made devices: they will be patents. The New Martian cities will become intellectual property powerhouses. And, as such, they’ll attract investment from wealthy investors, just as Columbus attracted investment from the court of Isabella and Ferdinand, and just as Silicon Valley attracted investment from wealthy individuals, pension funds, and venture capital firms.

And the New Martians won’t just export back to Earth. Given their location and lower gravity, they will also import and export goods and services to the asteroid belt—a sprawling collection of rocks between Mars and Jupiter containing trillions of dollars of metals, volatile gases, and other valuable materials. The implacable laws of orbital mechanics dictate that an orbitally refuelled SpaceX Starship can travel from Earth to Mars, or from Mars to the asteroid belt and back. But a Starship cannot make it from Earth to the asteroid belt without a refuelling stop at Mars. Therefore, Mars will act the role of Seattle in the Yukon Gold Rush. Everyone will fuel, refit, and sell their extracted raw materials there. And everyone will use the cities to let off steam, after years trapped in asteroid mining vessels. Zubrin even forecasts an interplanetary version of the “triangle trade,” which built the economy of New England: with Earth supplying high-tech manufactured goods to Mars, Mars supplying low-tech goods and food staples to the asteroid belt, and the asteroids sending metals to Earth. Mars could become the economic hub of the Solar System.

This sounds like science fiction. In fact, it sounds like the Solar System described in The Expanse—an award-winning set of novels that has been made into a highly-acclaimed popular television series. It also has echoes of For All Mankind, another popular television series that includes the earliest stages of Mars settlement and asteroid mining. Zubrin’s strength is taking concepts that sound like science fiction, then analysing the technological, economic, and political underpinnings that would be required to make them reality.

I have some quibbles with Zubrin’s vision. First off, he bases a lot of his economic projections on Martian real estate becoming an attractive financial asset. But, except for a passing comment in the book’s epilogue, he ignores the Outer Space Treaty of 1967. This treaty, with 122 signatories, forbids any nation from claiming an extraterrestrial object as its sovereign territory. So the United States cannot simply annex part of Mars (or the Moon) as the 51st state and extend American rule of law to that territory.

This has been a subject of academic debate for years, but now that extraction of extraterrestrial resources is on the near horizon, it has become much less theoretical. The US and China have diametrically opposed public interpretations of the treaty, with complex consequences. With the Artemis Accords (43 signatory nations and counting), the US is attempting to build a coalition of nations willing to take steps towards recognising property rights on extraterrestrial bodies. But it’s early days yet, and the consensus is fragile. It’s doubtful that the billions of dollars necessary to build a new Silicon Valley on Mars will be available until the legal framework of land ownership is nailed down.

Second, Zubrin makes a strong case that, in the long run, thriving cities on Mars will necessarily be populated mostly by native-born New Martians, not emigrants from Earth. However, we have absolutely no idea if it will even be possible for humans to be born on Mars. Our species has evolved in Earth’s gravitational field. We have no data on how humans will thrive and reproduce in lower gravity. At the furthest limit—zero gravity—the data is discouraging. Robert Heinlein was wrong: zero G is unhealthy for humans. From muscular atrophy to loss of bone density, to glaucoma, to immune systems disorders, astronauts who have spent 6–12 months on the International Space Station have experienced various health problems, from annoying to potentially debilitating. Many physiologists believe that the one-third Earth gravity on Mars should be sufficient to stave off these disorders and enable successful conception, gestation, and birth. But we don’t know. Until we have vastly more data from one-third-G centrifuges in Earth orbit, it’s irresponsible to hypothesise about tens of thousands of humans being safely born on Mars.

Lastly, Zubrin’s view of colonisation and settlement is very US-centric. There have been other models in recent human history. Australia was settled by British criminals. Although it has done well, the Australian frontier evolved very differently from the American one. Brazil was colonised—not settled—by the younger scions of the Portuguese upper classes, who came to extract as much wealth as possible as quickly as possible and had no intention of staying and building families. There are other examples. The steps outlined by Zubrin are necessary but not sufficient to achieve his vision of a thriving and self-sufficient Mars.

But these problems can be solved, whether through negotiating new treaties, or through better understanding of human physiology. Fundamentally, there is an entire new world there for the taking, with a land area equal to Earth’s. In the long term (centuries, not millennia), Zubrin explains that Mars could be terraformed into a planet where humans could walk on the surface without spacesuits and, someday, even without breathing masks. Humanity won’t be held back by either treaties or technical obstacles. Expansion is what humans do.

Zubrin quotes approvingly from the Turner thesis:

To the frontier the American intellect owes its striking characteristics. That coarseness and strength combined with acuteness and inquisitiveness; that practical, inventive turn of mind, quick to find expedients; that masterful grasp of material things, lacking in the artistic but powerful to effect great ends; that restless, nervous energy; that dominant individualism, working for good and for evil, and withal that buoyancy and exuberance which comes with freedom—these are traits of the frontier, or traits called out elsewhere because of the existence of the frontier.

This is the foundation of Zubrin’s concluding argument. Settling Mars isn’t just about making humanity a multi-planetary species. Settling Mars is about improving life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness for everyone on Earth.

John F. Kennedy correctly labelled space as “The New Frontier,” but we haven’t been treating it as a frontier. We’ve been treating it as a scientific curiosity, occasionally visited by hyper-qualified astronauts selected for their physical, mental, and emotional excellence. That’s not how a frontier works. The idea of crossing the Atlantic to settle in the New World attracted people who were dissatisfied with their lives in Europe. “People who did not ‘fit in’ with the Old World could discover and demonstrate that, far from being worthless, they were invaluable in the New.” Similarly, the American West was settled by malcontents, restless souls, and people who felt trapped by the crowds and smokestacks of East Coast cities. “Go West, young man” was not just an exhortation by Horace Greeley. It was the touchstone of an age when ambitious young men (and, eventually, women) could move to an “unpopulated” desolation and carve out a homestead or make a fortune. (Of course, America was not actually unpopulated, and the treatment of Native Americans was deplorable, but, luckily, abuse of native populations is one problem we won’t have anywhere in the Solar System.)

Society has changed, but human nature has not. A relief valve for the pressures of modern industrial civilisation is more needed than ever. The settlers will be required to improvise, adapt, and invent new technologies to overcome the challenges of their new frontier. As Zubrin claims, “without the opening of a new frontier on Mars, continued Western civilization faces the risk of technological stagnation.”

We’ve spent fifty years taking small steps into orbit and onto Earth’s moon. Settling Mars will truly be “one giant leap for Mankind.” It will unlock vast new resources, bringing the possibility of wealth and well-being to everyone on Earth. Zubrin writes: “the real lesson of the last century’s genocides is this: We are not endangered by a lack of resources. We are endangered by those who believe there is a shortage of resources. We are not threatened by the existence of too many people. We are threatened by people who think there are too many people.” Rather than squabbling over oil, water, and other resources here on Earth, we can lift our eyes to the endless wealth of the Solar System. Rather than endlessly jostling with our neighbours for lebensraum, we could give every nation or group as much living room as they desire.

The social, economic, and political problems of 16th-century Europe could not be solved within the boundaries of Europe. To find solutions, people had to zoom out, to reorganise society within a larger frame that included a New World. The same is true today. Earth’s problems are solvable, but they are not solvable solely on Earth. Zubrin has done a masterful job of summarising our challenges, our capabilities, and our future potential. And his central thesis is spot on: For humanity to thrive, we need to build a new world on Mars.