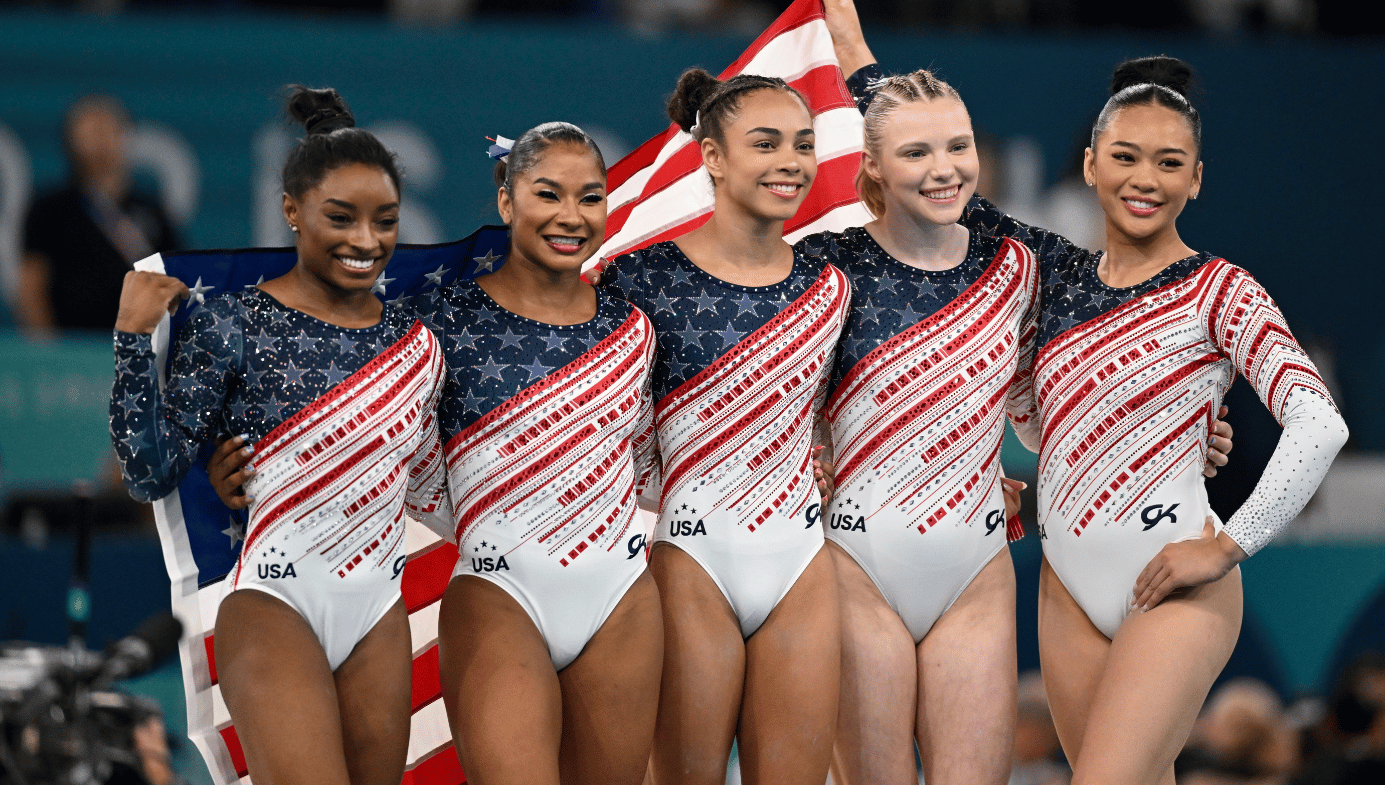

Like so many other people, I tuned in to watch the Paris 2024 Olympics’ Women’s Artistic Gymnastics a couple of weeks ago. I’ve seen women’s gymnastics before—but I’ve never watched it having just finished teaching an intensive university course on feminism. I couldn’t help but notice how revealing the leotards were—high cut, showing a good third to half of the gymnasts’ butt cheeks. That the uniforms were covered with sparkling crystals. And that the gymnasts—the youngest of whom is only sixteen years old—all seemed to be wearing makeup. Simone Biles could be seen on camera waiting for her score after an incredible tumbling routine dabbing carefully at her forehead. God forbid an Olympian should be seen to sweat.

I was going to write something predictably feminist about this—on the way in which asymmetric beauty standards are applied even in sport; or on the sexualisation of young girls (don’t tell me there aren’t men out there titillated by the flashes of barely-covered crotch while the girls flip around the uneven bars or tumble throughout the floor exercise)—indeed, the continued sexualisation of young girls even after a huge sexual assault scandal in the gymnastics community. But then I read the rules and discovered that the International Olympics Committee is not making female gymnasts wear leotards. They can wear shorts or pants, a shirt or singlet, a tracksuit or jacket, and/or a leotard, leotard with skirt, or unitard.

Indeed, the German women’s team wore full-length unitards to the Tokyo 2020 (postponed to 2021) Olympics, in explicit resistance to the sexualisation of the standard gymnastics uniform. (Their uniforms still had crystals on them, though. One battle at a time!) Some (but not all) of the German women gymnasts competing in the Paris 2024 Olympics are wearing new versions of the unitard. This implies that all the other women gymnasts must have chosen the high-cut bikini line, the sparkling crystals, and the makeup, and if they have chosen those things, there’s nothing left for a feminist to complain about, right?

This is a familiar line of reasoning when it comes to the so-called “gender equality paradox”: women in comparatively egalitarian countries are free to pursue high-powered careers, to decide not to have children, to put their children in childcare, to organise their home lives in whatever way they like, etc. And yet they choose to have children and stay at home with them, or to enter female-dominated or female-typical careers and industries. They were free and this is what they chose; nothing for a feminist to see here.

However, things are not quite so simple. A recent paper by a research team from Sweden—one of the countries most often cited by those invoking the abovementioned paradox—asked Swedish women about their perception of norms of femininity. The women named beauty norms as the most important of these, although they noted that such norms must be conformed to in secret. As the study’s authors put it,

the participants stated that women have to pretend that their beauty comes “naturally,” and they also discussed the importance of keeping up an image of wanting to be healthy instead of wanting to lose weight … women who diet are assumed to have low self-esteem. … Some participants further described that they felt looked down on when someone found out they were spending time on something as superficial as their appearances, and therefore it was important to pretend that they did not.

Norms are moralised expectations. Norms are not coercion; there can be norms, and it can be true that a woman is free to violate them. But thinking in terms of norms rather than coercion is helpful, because it allows us to ask what the social costs are for violating the norm, what the social rewards are for conforming to it, and what a rational response to such costs and/or rewards would be. If women suffer serious professional consequences for violating beauty norms, then most will conform to beauty norms in order to avoid those consequences. Such a woman is still free to choose whether to adhere to beauty standards or not, but there is also very much something for a feminist to see here. A feminist can be concerned with the social norms because of the incentives they create and the rational choices that women make in response.

And there are not just norms. There’s also tradition, there’s what everyone else is doing (even if they wouldn’t mind if you did things differently, being different can itself be uncomfortable), there’s the ease of just going along, there’s the million other things to think about, there’s the is this really the hill I want to die on?

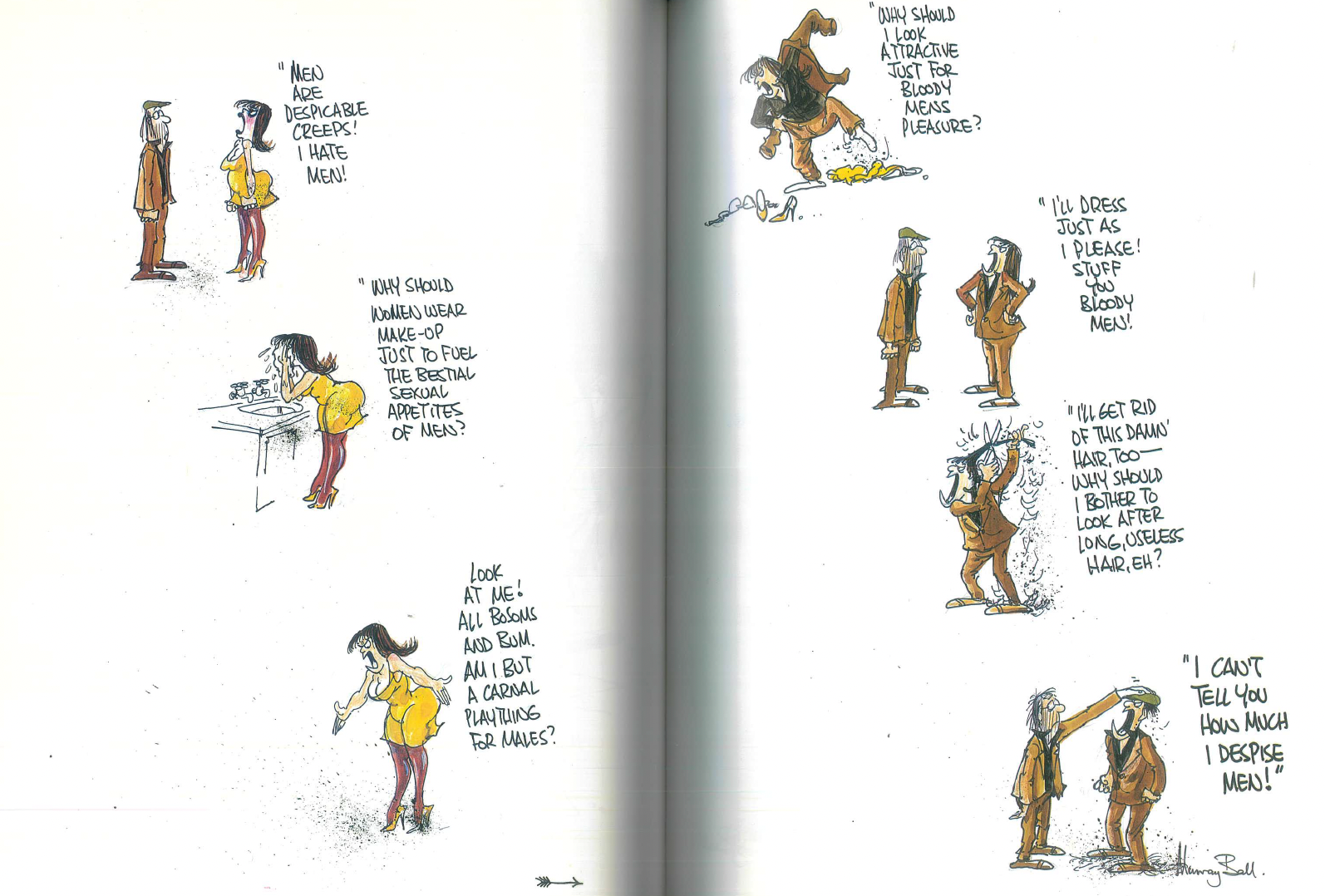

In his comic book The Sisterhood (1993), which satirises the feminist movement, Murray Ball gets at least one thing right: feminine norms of appearance put women in a double bind. If a woman presents in a feminine way, she’s participating in, and thereby acquiescing to, her own sexual and/or beauty objectification; and if she presents in a masculine way, then she’s adopting the male standard, and is thereby “male-identified,” failing to celebrate and affirm women’s difference from men—and this is bad because, we are told, women should not have to be the same as men in order to be respected and taken seriously.

Are female gymnasts in this same double bind, where wearing leotards would make them self-sexualising, and wearing trackpants would make them imitators of men in order to gain respect, and either way they lose? It’s hard for me to take this idea seriously: athletes need fabrics that move and breathe; they need to be able to sweat without worrying about ruined makeup; they need to be able to run without worrying about their leotards riding up into their butt cracks. They do not need to be plastered in 10,000 Swarovski crystals in uniforms that took 4 years and 50 people to make. The audience does not need titillation. (Or if the audience needs titillation, there should be sexual equality in that. Let’s see some male gymnasts’ butt cheeks.) What we might want to say about standards of presentation in everyday life doesn’t seem to apply nearly as well to the athletics context.

Many people are celebrating the fact that Paris 2024 is the first time the Olympics has ever achieved gender parity, meaning parity in the numbers of male and female athletes. Before this Olympics, there had been recent breakthroughs for women’s sport, such as the huge support in Australia for the national team, the Matildas, in the 2023 FIFA Women’s World Cup. There’s something contradictory in the messaging here. On the one hand, female athletes are seen as breaking barriers just by participating in their sport, by being sporty, winning medals, and smashing previous records; and at the same time, such female athletes are reinforcing stereotypes by making sure they look pretty while they compete.

Not all sports have this culture; there’s something specific going on in gymnastics. The question is what it will take to stop it, and whether Germany’s efforts will eventually pave the way to uniform parity between the sexes, or whether like so many other of feminist history’s attempts at dress reform (as Susan Brownmiller discusses in her book Femininity) this one will end in failure—and the Germans themselves will be back in leotards in a few Olympics’ time.